Sometimes the melody comes first, sometimes the words. On this occasion, as Jim Seals sat in a Woodstock, New York, recording studio, they came together. It was 1970, and Jim, 28 years old with long brown hair and a full goatee, was taking a break during the recording of his duo’s second album.

By many measures, Seals and Crofts were a successful group. Though their first album hadn’t cracked the Billboard 100, Jim and his partner, Dash Crofts, were opening for acts like Chicago, the Guess Who, and Eric Clapton, getting their music heard by huge crowds in famed venues like the Fillmore East and the Boston Tea Party. But the pair wanted to do more than just play cool tunes. They wanted their placid words and lush harmonies to soothe a world reeling from the nonstop chaos of the Vietnam War, the assassinations of Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert Kennedy, and the unending riots in the streets. They wanted to make a difference.

The melody that came to Jim that day was simple and sweet, and it nudged a series of images into his mind. Curtains hanging in a window, a newspaper on the sidewalk, music coming from a neighbor’s house, a man walking up the steps and through the front door, a smiling woman waiting for his arrival. Home.

The chorus came to him now, so effortlessly that it felt as if the song was writing itself:

Summer breeze, makes

me feel fine

Blowin’ through the

jasmine in my mind.

In Jim’s imagination, he was a boy again, before his parents had split up and his life changed forever. The house he was remembering wasn’t anything special, a narrow shotgun shack identical to dozens of others around it. But it was home, a solid, sure thing to a six-year-old boy. The melody and words of this new song carried him back as if he were actually there.

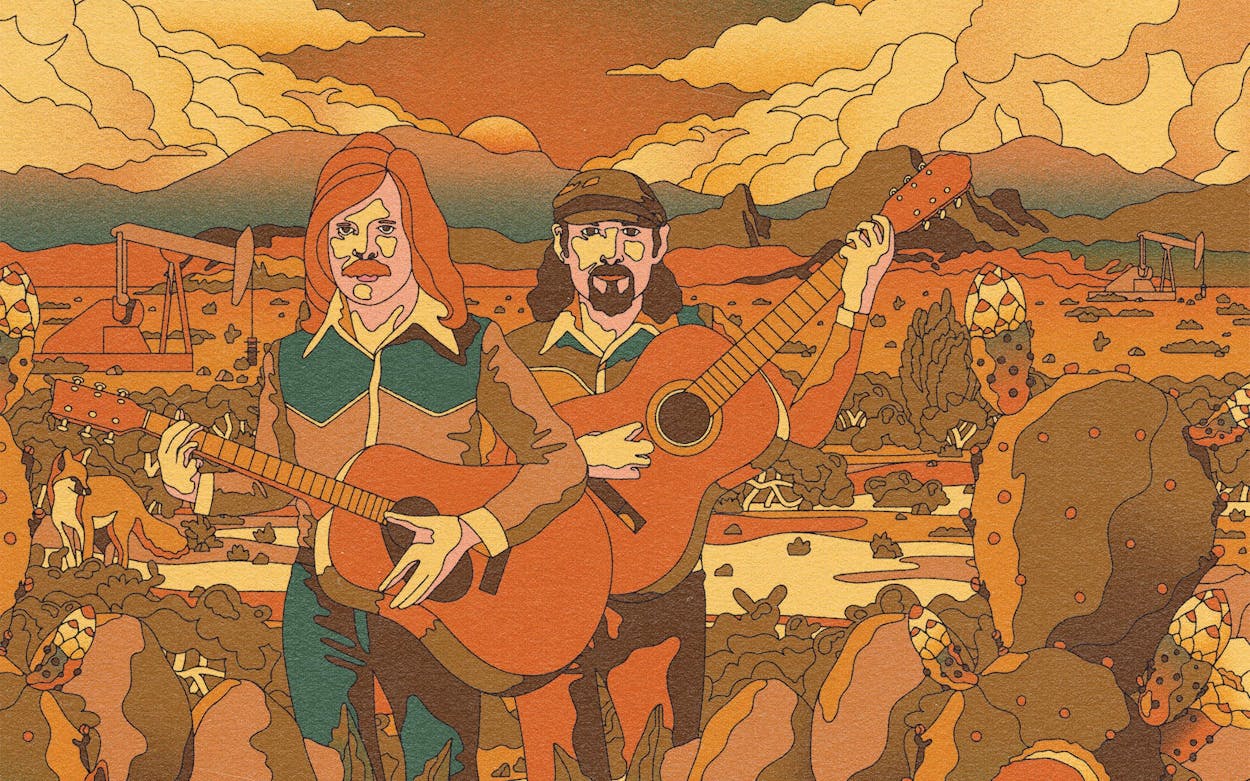

It took a couple of years for Seals and Crofts to record “Summer Breeze” to their satisfaction, but when the song—with its catchy hook and indelible chorus evoking sunnier times—finally hit the airwaves, in 1972, Jim’s nostalgia became everybody’s. Seals and Crofts went from being a promising opening act to bona fide rock stars, with their own jet plane and thousands of fans waiting at every tour stop. The singles that followed made the duo paragons of a new genre, soft rock, which turned its back on the excesses of sixties hard rock and attempted to establish a peaceful vibe for a new era. Their smiling, bearded faces were everywhere as soft rock was embraced by millions and ruled the pop charts for much of the rest of the seventies—even as it was reviled by critics, who pointed their fingers at Southern California as the likely source of this plague of mellow.

Sitting in his house in tiny Rankin, Texas, a retired oil field roughneck and guitar player named Wayland Seals knew better. Wayland was Jim’s father, and he knew firsthand that L.A. wasn’t soft rock’s sole origin point. In fact, some of the genre’s deepest roots ran under the sidewalks and streets of the very town he lived in—and then pushed out through the barren fields of West Texas. It was a vast, desolate area, one that Wayland knew well, one where young men with pitch-black grit under their fingernails and dried mud in their hair dreamed of country music every day and played it every night.

Jim Seals’s family moved to West Texas for the same reason most families did: oil. His grandfather Fred Seals came first, in 1919, from Tennessee, to Desdemona, a boomtown east of Abilene. Fred, who was half Cherokee, got a job as a pumper. Later he sent for his wife, Cora, and their only child, seven-year-old Wayland.

The Sealses were a musical family—Cora’s uncle had been a well-regarded fiddler, and both Cora and Fred played the banjo, sometimes picking tunes on the front porch. When Wayland was eight or nine, Fred showed him how to play the guitar. The boy got pretty good; in his teens he played with a young singer named Ernest Tubb, who eventually went on to bigger things.

Wayland, though, followed his father into the oil fields. He married young, and he and his wife, Clodell, had a son, Eddie, in 1937. But Clodell died three years later, and the boy was taken by her parents, who raised him in Stephenville. A few years later, Wayland married a woman named Susan, and in 1942 their son Jim was born.

When Jim was four, the family moved to Iraan, a recently founded boomtown. Wayland worked for Shell—first as a roustabout, digging ditches, and then as a pipeliner—and he and his family lived in a modest company house surrounded by derricks that stood like trees in a forest. Years later, Jim would remember taking a train ride through the region. “There were oil rigs as far as you could see,” he said. “And the stench was so bad you couldn’t breathe.”

Wayland was an old-fashioned man, proud of his ability to do physical labor. He loved going to work, and he loved coming home at the end of the day and pulling out his guitar, playing country and western songs he heard on the radio and songs he had written. Sometimes he hosted casual jam sessions and sing-alongs in his living room. Neighbors would stop by, bringing dinner and cakes, and everyone—including Susan, who played the Dobro—would sing, sometimes long after dark.

Jim, a shy, sensitive boy, was five or six when a fiddler named Elmer Abernathy visited the Seals home. The boy was mesmerized by the man’s instrument, and the next day Wayland, who’d always wanted a family band, ordered him a fiddle from the Sears catalog. When it arrived, Jim tried to play it but couldn’t figure out where to put his fingers or how to draw the bow, so he slid it under his bed.

One night a year later, Jim had a dream that he was playing his fiddle. “It was the most beautiful music,” he said. “I could play anything. When I woke up, I remembered the position of my fingers in the song and pulled out my fiddle. I played the song from my dream, and it wasn’t as good as the dream, but it was a start.”

Jim began practicing, and soon he was sawing along to songs he heard on the radio by Bob Wills, Hank Thompson, and Hank Snow. Most evenings his dad would come home from work and play with him, and soon they were performing songs together. Just as Wayland’s father had done, father taught son—fiddle tunes, country tunes, hoedowns, polkas, waltzes, pop songs.

Rural West Texas had a long tradition of families performing music together. There wasn’t a lot to do on the farms and in the camps, and families would play music to fill the space—and maybe to make some money. Some of them turned their hobbies into careers. Bob Wills, the father of western swing, and Hoyle Nix, who would form the West Texas Cowboys in Big Spring in 1946, both came from musical families in West Texas.

Wayland, who had written dozens of songs about rambling, loving the wrong person, and living the oil field life, performed with several different bands at clubs and VFW halls, and he and Jim would play barbecues, church picnics, and ranch parties. They’d go to the nearby home of prosperous rancher Charlie Chandler and sing for his family. Jim remembered, “Old Man Charlie would ask us to play ‘Soap Suds Over the Fence’ or ‘Ida Red.’ When we’d get to ‘Rye Whiskey,’ tears would be rolling down his cheeks.” The two occasionally crossed paths with Jim’s half brother, Eddie, who was singing in a gospel quartet called the Rhythmaires.

In 1952 Wayland entered Jim in the famed Texas Fiddlers Contest and Reunion in Athens. There were three categories: for kids, grown-ups, and older folks. Jim played the venerable fiddle tunes “Sally Good’n” and “Listen to the Mockingbird” and won his division, then battled the winners of the other two and beat them as well. Wayland won the guitar contest. “Both of us were state champions,” said Jim. “We were driving back to West Texas with the windows down, whooping and hollering.”

Though Jim’s father was his musical partner, in matters of temperament the boy was closer to his grandfather. Fred was a spiritual man who had a way with wild animals. Jim once saw him stop the car and call a squirrel, which leaped inside; a fellow pumper witnessed Fred petting a fox. Jim swore that watches would stop on his grandfather’s wrist and radios would turn to static when he walked into a room. He loved his grandfather, who taught him how to sing two tones at once, as indigenous people do in Asia and Alaska. In quiet moments Fred would tell him, “Baby, you’re a dreamer, and that’s all you’ll ever be.” Coming from his grandfather, that was a compliment.

Jim wasn’t the only dreamer in the house. When his little brother, Dan, who was born in 1948, was four, Wayland stood him on an apple crate next to a stand-up bass bought from a music store in Odessa and showed him some notes. Dan was a fast learner, and soon he was plucking the bass alongside his father and brother. Dan was crazy about music. “I’ve loved to play and sing from the moment I knew what it was,” he said decades later. Wayland finally had his Seals family band, and Fred was enormously proud of his grandsons. “Someday,” he told them, “you babies will play before kings and queens.”

One day in 1955, Jim came home from a gig in Abilene and told his father that all the bands there were playing a new kind of music, one that was modern, wild, cool. They called it rock and roll, and Jim wanted to play it too. By then the Seals family was living in Rankin, a small West Texas town 27 miles from Iraan, and they had brought their house with them—uprooted and hauled to its new location by Shell. Though there was no place to play rock and roll in Rankin, you could hear it at a spot just outside town called Flat Rock, where the teens went to neck and listen to radio stations from as far away as New Orleans. Sitting in their cars in the darkness, the kids heard an entirely different universe, a place where Little Richard screamed like a maniac and saxophones blew hard into the night. Jim, who was thirteen, knew that his half brother Eddie played the sax, and he told Wayland he wanted to as well. Wayland bought him one, and as the boy had done with the fiddle, he sat in his room learning on his own, dreaming of joining a band.

He didn’t have to wait long. While working at Midland television station KMID, where Jim fiddled in the house band of a country and western TV show, he met a young man named Dean Beard, who was known as “the West Texas Wild Man.” Beard was the pianist in a rockabilly band, and when he heard that Jim played sax, he asked him to audition. Soon, Jim was performing with Beard’s new group, the Crew Cats, at proms, dances, and nightclubs. Jim would take the bus to Abilene, play all weekend, and get back Monday for school.

The world was changing—and Jim was changing with it. As he got into rock and roll, he got into the rock and roll lifestyle too. He saw Elvis perform in Sweetwater and couldn’t take his eyes off him. Jim, a short, thin teen, grew out his hair and sideburns and started wearing white T-shirts with rolled-up sleeves and a black leather jacket. It was an unusual look for a place as remote as Rankin, and not everyone knew what to make of it. “He was kind of like a black person,” remembered his friend Bud Poage, “with his air and actions and things.”

One night, Beard’s drummer quit before a gig at a junior college in Cisco, a town 45 miles east of Abilene. Also on the bill was a country band with a drummer named Darrell “Dash” Crofts, who had been born in Cisco in 1938. Dash’s father, Sutton, was a cattle rancher, as was his grandfather, who had run a large spread near Johnson City a century earlier. Though Dash loved growing up on ranches, he was more excited about music than about cattle—first classical, then jazz, country, and rock and roll.

Beard asked Dash to play with the Crew Cats that night—and after the gig, he became the group’s permanent drummer. Dash was outgoing, something of a joker, the opposite of the shy, withdrawn Jim. But as the band toured West Texas, the odd couple became friends, singing along with the car radio, talking about their favorite jazz records (both loved the bop saxophonist Art Pepper), fantasizing about becoming rock stars.

Jim was still occasionally performing with his father, and in 1957 and 1958 he helped Wayland, who was in his mid-forties, realize a lifelong dream, accompanying him to an Abilene studio to record four of his songs, including “I’ll Walk Out,” an old-fashioned country weeper. “I’ll walk out if you don’t love me,” sang Wayland, sounding truly stricken. “I could say that I’ll forget you, but I’d only tell a lie.” The singles were released on a tiny Abilene label, sold in local pharmacies and dry-goods stores, and played by a Midland radio station. Soon they disappeared from view, though the lyrics of “I’ll Walk Out” came to life when, shortly after that final recording session, Susan left Wayland and took ten-year-old Dan with her.

Jim stayed with his father, but as it turned out, he didn’t stick around for long either. In June, the Crew Cats’ manager, Slim Willet, made him and Dash a life-changing offer: to go on the road with the Champs, a Los Angeles group that had recently scored a number one hit with the saxophone-powered “Tequila.” The instrumental group was on tour, and the sax player and drummer had just quit. Willet told the band’s handlers that he knew two young guys who could take their place. Jim, whose favorite song was “Tequila,” jumped at the chance, as did Dash. The teenagers met the Champs before their next gig, in Baton Rouge, where they were on a package tour with Connie Francis and Danny and the Juniors. Fifteen-year-old Jim was in awe. “They had on these fine suits and all this jewelry,” he said. “They looked like kings.” Then the band drove to the auditorium, where two hundred people waited outside. “They went crazy when they saw us and started ripping at our clothes. It was like Beatlemania.”

When the tour was over, Jim and Dash were invited to join the band full time, which entailed moving to Los Angeles and dropping out of school. Wayland, who had already said goodbye to two sons, reluctantly allowed Jim to drop out of Rankin High School and leave Texas.

Soon, Jim and Dash were rock stars, making $500 a week, buying mohair suits, partying in the L.A. music scene, touring nonstop. But eventually it all began to feel like drudgery. “Tequila,” once Jim’s favorite song, became a torment. Sometimes he had to play it two or three times a day. “I never wanted to hear it again,” he said. So in 1965, both men quit. Too much was happening in L.A., and they wanted to be a part of it—whatever it turned out to be.

By 1968 California was ground zero for the Age of Aquarius, and Jim and Dash were living in L.A. in a three-story house on Sunset Boulevard surrounded by spiritual seekers. The house was owned by a woman named Marcia Day, who was managing their current band, the Dawnbreakers. Day was a savvy manager who dispatched the group to make money and gain experience in Las Vegas, where Jim often saw Eddie, who was part of a country-comedy group called Harper Valley PTA. But Day, unlike many L.A. show biz operators, was also a deeply religious person. She was a member of the Baha’i faith, a religion founded in the nineteenth century by a Persian mystic named Bahá’u’lláh. Its central tenet is unity, including the belief that all prophets and messiahs, from Jesus to Moses to Muhammad to Bahá’u’lláh, spoke of the same God. Baha’is profess faith in the oneness of mankind and the equality of everyone.

Day held Friday night “firesides” at her house, where different Baha’i speakers would talk and then engage in earnest rap sessions about the words of Bahá’u’lláh and the importance of tolerance. The house was filled with sincere aspirants and also scenesters and hangers-on. André the Giant showed up; so did the child actor Leif Garrett. “We called it the watering hole,” said Jim. “All the little birds came to drink and eat. The drug addicts and the lost all ended up at Marcia’s house.”

Neither Jim nor Dash had grown up particularly religious, but they felt that in Baha’i they had found a modern faith that spoke to them. In 1967 they converted, first Dash (who had married Day’s daughter Billie Lee), then Jim. “It was the first thing I heard in my life that made sense,” Jim said. His connection to his new faith grew even stronger when, at one of Marcia’s get-togethers, he met a fellow Baha’i named Ruby Jean Anderson, who had been born in Houston but was raised in L.A. and wanted to be an actor. Ruby was African American, and even in L.A. in 1969, dating across racial lines was a daring move. But the two fell in love, and the Baha’i community openly welcomed their relationship.

Soon, Jim asked Ruby to marry him. She said yes, but there was one obstacle: before a couple who were members of the Baha’i faith could get married, they were required to obtain the permission of their parents. Ruby’s mother and father gave their blessing to the union, as did Susan. But Wayland had been around few black people in his life, and he carried the sort of prejudices that were common among men of his time and place. No, he told Jim in a letter, he would not give his permission. Jim, disappointed and genuinely distraught—there was no way around his religion’s stipulations—replied with a letter that addressed his father with an emotional honesty that was uncommon between the two men. “You raised me to believe that we should have love in our hearts for everybody,” he wrote. “Has that changed?” Then he waited for a response. Jim knew how difficult the matter was for his father, a proud man long settled in his ways of thinking. Finally, he got the answer he was hoping for. Yes, Wayland told Jim, you can marry the woman you love.

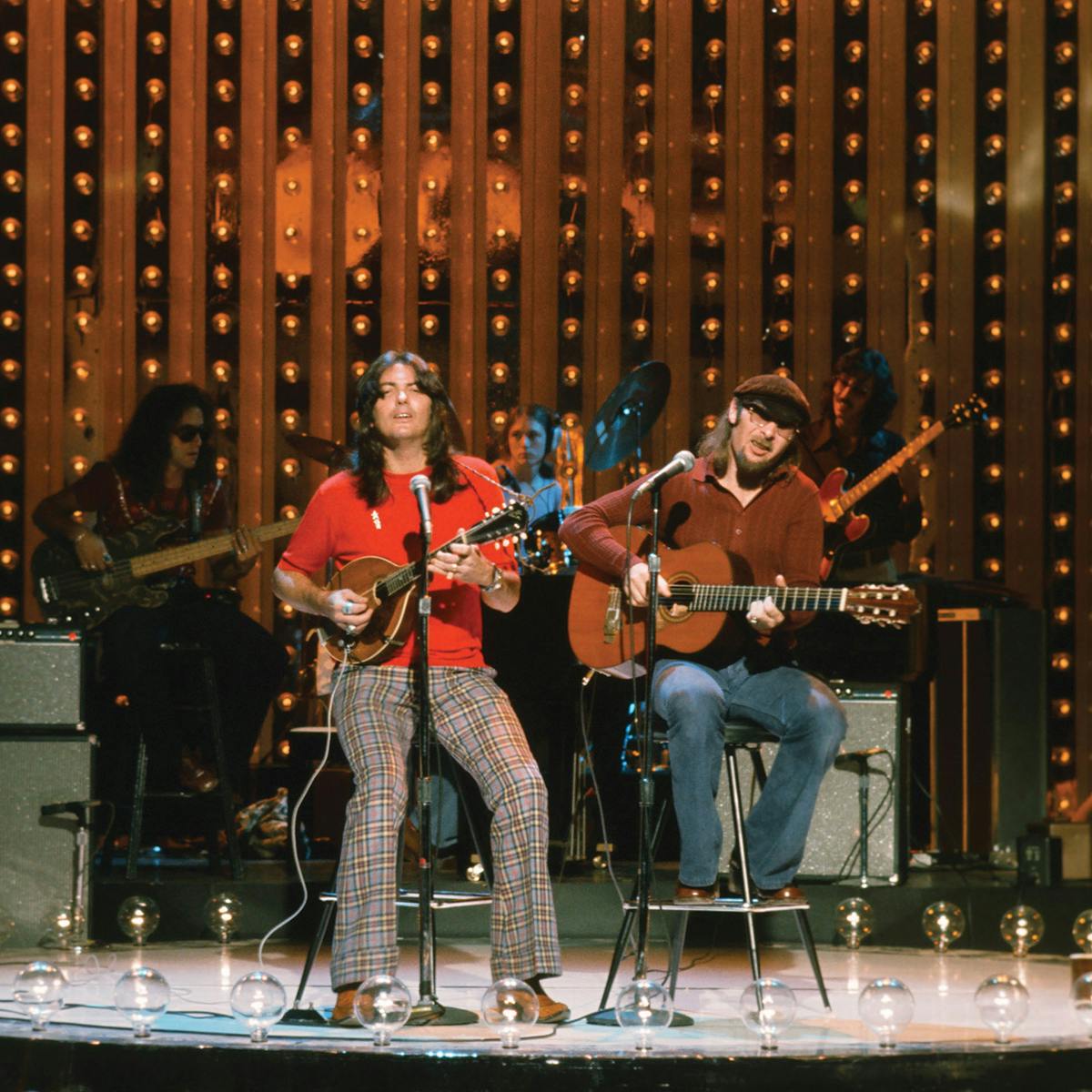

Over the next couple of years, Jim and Dash’s spiritual change went hand in hand with a musical change. Jim had moved on to a third instrument, acoustic guitar, while Dash had learned the mandolin. After years of working in bands, the two men sought something new. “We were tired of loud music,” said Dash. “We were tired of rock and roll.” Now they spent countless hours together playing their unamplified instruments and singing. They had been performing together for so long that they would finish each other’s sentences and hear harmonies in each other’s melodies. Jim sang most of the lead vocals, while Dash, who had a smoother voice, sang up high.

Their new music sounded elegant, stately. Sometimes it had an Old English lilt; other times, it resonated with an almost Middle Eastern or—when Jim sang with two tones, as his grandfather Fred had taught him—Asian vibe. Fred had died in 1964, but his dreamlike spirit lived on in Jim, as he and Dash fit their new music with their new faith. “We have become real for the first time in our lives,” Dash would say. The two men saw their music as art that rejected the violence and turbulence of the times, which had come unnervingly close to them; Jim’s hairstylist was Jay Sebring, who was murdered by the Manson Family, along with the actress Sharon Tate, in August 1969.

Dash and Jim made a pact, a promise to each other to let as many people know about the Baha’i faith as they could. Jim’s lyrics—once about girls and dancing—now made references to Baha’i beliefs. Sometimes, his words were inscrutable (“You are seldom’s sister how to tell my never’s friend”), sometimes excessively quaint (“How I long with all my soul to quaff the mystic fragrance of the ancient of the old”); always, they were positive.

And when they started performing the new songs in public, audiences responded. During their second gig as a duo, at L.A.’s Troubadour, they played the handful of songs they had written, and the audience was so enthusiastic they played them all again. Dash and Jim felt they were on the edge of something entirely original. “We thought we’d discovered a new way of using the English language,” Dash later told a reporter.

During his first decade in L.A., Jim all but fell out of touch with his baby brother Dan, who had followed his own curious musical path. When Dan was ten, he and his mother had settled in Dallas, where, like Jim, he found himself moving beyond the country music of his youth. Dan fell in love with the voices of the soul singer Sam Cooke and the R&B shouter Jackie Wilson, and he revered the Beatles; he would occasionally affect an English accent, for fun. By the time he was seventeen, he was writing songs and singing and playing sax in a rock and soul cover band called the Playboys Five. When they broke up, he joined another band, Theze Few.

One of his bandmates was a local singer and keyboard player named John Colley. During their downtime, he and Dan started singing together and discovered that their voices meshed well, with Dan usually singing lead and John a high harmony. They were obsessive and methodical about it, taking apart the harmonies in Everly Brothers songs and putting them back together.

In 1967 Theze Few went psychedelic, changing its name to Southwest F.O.B. (which stood for “Freight on Board”). Their debut single, “Smell of Incense,” made it on to the Billboard charts, and the band released an album on a subsidiary of Stax Records, home to Otis Redding and Sam & Dave. Soon, they were opening for acts such as Three Dog Night and Led Zeppelin, the sort of gigs most teen bands could only dream of.

But by 1969 Dan and John found themselves tiring of the rock and roll life—the drugs, the band infighting, the noise. When they could, the two would get together and play music, just acoustic guitar and piano, and they found they liked it better than playing in the band. Fed up with the Dallas scene, they decided to move to L.A. to make it as an acoustic duo under the name Colley and Wayland, which was Dan’s middle name.

The first person Dan looked up was his brother. The two were different in many ways. Dan was tall and extroverted; Jim was short, tense, and introspective. Yet the two kids from West Texas shared a distinctive musical bond, raised by a father who lived and breathed old-fashioned country music. And though both had initially followed in Wayland’s footsteps, they’d eventually chosen their own paths—through rockabilly, rock and roll, R&B, and even psychedelia. Now both of them had, separately but for very similar reasons, left all of that behind to search for a quieter, more inward-looking sound, each of them as one half of a duo.

Jim took his brother under his wing, helping Dan and John record a demo tape and get gigs. Jim, by now a music-business veteran, emphasized how important a group’s name was and advised them to change theirs. “Colley and Wayland” didn’t have much of a ring to it, he told them. Dan had always been a Beatles fan, and Jim remembered the fake British accent he used to affect, so his new sobriquet was easy. John, by contrast, reminded Jim of an old gunslinger, so he recommended adding a famous outlaw name. Lose a consonant too, suggested Jim.

The duo took his advice. From then on, they would call themselves England Dan and John Ford Coley.

In January 1971 Stereo Review magazine ran a story on Jim and Dash, pegged to the release of their second album, Down Home. “Introducing Seals and Crofts,” read the headline. “Here it is Post-Rock already, and a pair of neoclassic synthesizers has arisen to offer a proactive sample of what may turn out to be the sound of the Seventies.”

That sound was soft rock. Of course, Seals and Crofts weren’t the only band playing it. The Carpenters, John Denver, and America were also making pleasant, melodious, nonthreatening music. After the upheavals of the late sixties and early seventies—the assassinations, the race riots, the violence at Altamont, the deaths of Janis Joplin, Jimi Hendrix, and Jim Morrison, and the ongoing cruelties of the Vietnam War—that seemed to be what millions of people wanted.

Seals and Crofts’s first three albums, released between 1969 and 1971, were sweet, folky records filled with baroque instrumental flourishes, lush harmonies, and spiritual lyrics. “We all live in the year of Sunday,” they sang. “So many things are in store for us.” The albums were smooth and slick, featuring studio musicians the duo had met while doing session work themselves. Jim occasionally harked back to his youth, playing fiddle on a couple of songs and doing some two-tone singing too.

But Seals and Crofts would have been just another pair of polite, bearded longhairs if it weren’t for “Summer Breeze.” The song, which had come to Jim so effortlessly in the Woodstock studio in 1970, proved hard to commit to vinyl. The duo tried to record it during those Woodstock sessions for Down Home, but Jim wasn’t happy with the results. The tempo was wrong, he thought, too rushed. Seals and Crofts tried again for their next album, 1971’s Year of Sunday, but Jim was unhappy with the drumming. The song needed a mellow, ruminative feel, he thought, but it had to have some snap to it too.

Finally, in 1972, producer Louie Shelton flew the bass player Harvey Brooks, who had played on Down Home, to L.A. to try again. Brooks knew how to lay back on a song while still propelling it (he had played on both Bob Dylan’s Highway 61 Revisited and Miles Davis’s Bitches Brew), and this time the veteran kept the song together. The opening riff was played by Dash on the mandolin, Brooks on the bass, and someone (Shelton thinks it was Dash) on a toy piano bought at a Toys “R” Us. It was a simple melody, moving up and down in singsongy fashion, the innocent tone of the piano making the riff even more evocative of a time long gone.

Then Jim began to sing:

See the curtains hangin’ in the window

In the evening on a Friday night

A little light a-shinin’ through

the window

Lets me know everthing’s all right . . .

The song was three and a half minutes of dreamy yet buoyant nostalgia, as seen through the eyes of a man whose life had undergone profound transformations—but who had never let go of where he came from.

“Summer Breeze” almost went nowhere. By the fall of 1972 the album Summer Breeze had been out for a couple of months, but the title single—the song the duo had worked so hard to perfect—had barely charted, and their label informed them it would do no more promotion. While Jim and Dash were on tour in Boston, Marcia Day, shrewd as ever, convinced them that while they were there, they should make a pilgrimage to one of the city’s most popular radio stations and play “Summer Breeze” for a DJ. Day knew that in an often impersonal business, a personal touch can make all the difference. She made the appointment, her boys arrived with the album, and they played the record for the DJ, nervously watching as he listened intently to the song they’d worked so hard to get right. When it was over, he looked up and delivered the news: “Summer Breeze” was going into rotation.

“I thought I was gonna have a heart attack,” Jim later recalled. It was the break they had been waiting for. The wistful song quickly caught on in Boston; other markets, like Philadelphia and Dallas, soon followed. When Jim and Dash got back to L.A., they heard “Summer Breeze” on the car radio. Not long after, they had a show in Ohio. “There were kids waiting for us at the airport,” remembered Jim. “That night we had a record crowd, maybe forty thousand people. And I remember people throwing their hats and coats in the air as far as you could see, against the moon. Prettiest thing you’ve ever seen.”

Other hits followed: “Hummingbird,” “We May Never Pass This Way Again,” and “Diamond Girl,” which in the spring of 1973 was pouring out of every car stereo in the country. The duo bought a private jet and toured incessantly. After every show they would come out and sit at the edge of the stage and hold firesides about the Baha’i faith with curious fans. In 1974 they played the California Jam, along with Deep Purple and the Eagles, in front of hundreds of thousands. When Jim pulled out his fiddle for a hoedown on “Fiddle in the Sky,” throngs of sunbaked hippies clapped along.

Seals and Crofts were one of the biggest bands in the country, but they were mocked as well as cheered. “Folk-schlock,” wrote New York critic Robert Christgau. The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Rock called the duo “undoubtedly the super wimps of the seventies.” Seals and Crofts had become icons of soft rock, a genre that was seen by many as a betrayal of the radical promises of the music of the sixties, when the airwaves had been heavy with calls for revolution, racial justice, and an end to the war. Now, by contrast, pop groups were singing sentimental love songs over mushy keyboards and gentle acoustic guitars. There had always been acts like that—during the sixties the Rolling Stones shared the charts with the likes of Sonny and Cher—but by the mid-seventies Bread, Barry Manilow, and Captain & Tennille ruled the radio and the record stores.

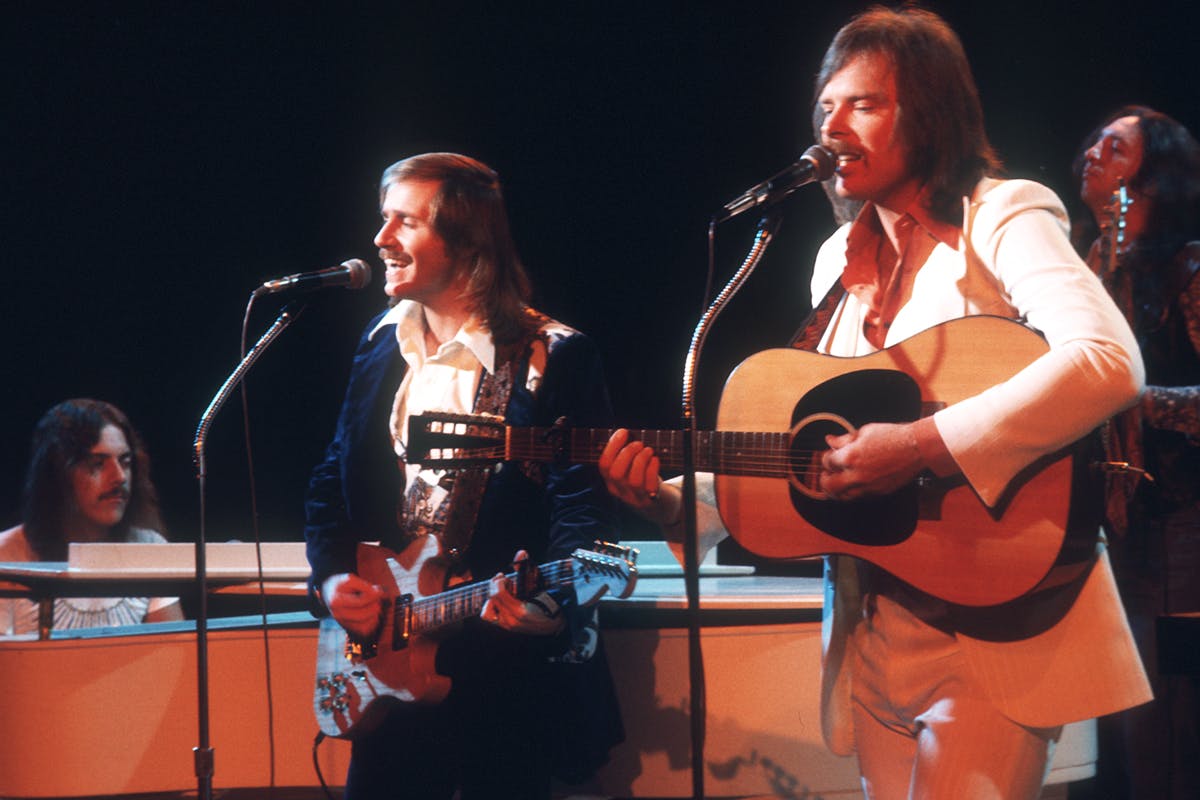

In 1976 another group joined their ranks: England Dan and John Ford Coley. The duo had been signed to A&M Records in 1970 and released a pair of albums. The two cowrote most of their mellow pop tunes, but they couldn’t find the formula to crack the American charts, even though they toured constantly, opening for acts such as Poco and Seals and Crofts. (By then, Dan and John had also become Baha’is.) In the American Bicentennial year their manager brought them a sugary pop song by the Nashville songwriter Parker McGee called “I’d Really Love to See You Tonight.” With Dan’s earnest vocals and John’s harmonies, it hit number one on the easy listening chart. The faces of the two men—with bushy mustaches and long, styled hair—were everywhere, especially after the follow-up, “Nights Are Forever” (also by McGee), also made the Billboard Top 10.

In August 1976 Seals and Crofts and England Dan and John Ford Coley each had songs in the Billboard Top 10—one of the rare times two siblings have ever accomplished that. Their polished music was a million miles away from those raw front-porch jam sessions they had been part of as kids in Iraan and Rankin. Though you could still hear some of their roots in their contemporary pop—Jim’s fiddle showed up occasionally, and Dan’s drawl never quite left him—they had almost completely reinvented themselves.

Dan and John had two more hits, neither of which they wrote (“We’ll Never Have to Say Goodbye Again” and “Love Is the Answer”), and Jim and Dash had one, which, true to form, they did (“You’re the Love”). But music trends come and go. Just as soft rock had been a reaction to the intensity of sixties hard rock, new genres arrived and announced that the mellow era was over. First came disco, with its brisk tempos and celebration of gay, black, and Hispanic urban subcultures, then punk rock, which sneered at anything soft and complacent.

Neither Seals and Crofts nor England Dan and John Ford Coley fit into this new world, and in 1980 both duos broke up. Their careers as hitmakers had lasted only a few years, but they were fruitful ones. Between them, the two acts had racked up two platinum albums, five gold albums, and seven Top 10 hits. And though soft rock has never again dominated the way it did in the mid-seventies, the genre has endured. You hear it almost anytime you go to a doctor’s office or an airport or anytime Shawn Mendes or Ed Sheeran open their mouths. Soft rock is forever.

For Seals and Crofts the music was essentially over. Jim and Ruby moved to Costa Rica, where they raised their three children and ran a coffee farm. Dash lived in Mexico with his wife and two children and then in Australia. For years neither man played much music. They were burned out and wanted to live something approaching normal lives.

Dan and John weren’t quite so ready to move on. John did a little performing and went into acting, while Dan kept playing music in earnest. At first he tried to continue as a pop performer, releasing his debut solo album in 1980 under the moniker “England Dan Seals,” but it went nowhere; neither did a second LP. He was audited by the Internal Revenue Service, which seized his assets. Married with several kids and living in Nashville, Dan found himself at a crossroads, and at age 35, he resolved to return to his West Texas roots and try to make it as a country artist. “I like rock,” he said in 1983. “I love country. Country comes from way down inside. It’s what I was raised on.”

Nervous about undertaking such a big shift, he made a trip to Rankin to talk to his father, who reassured him that things would be fine if he followed his dream. Dan also decided that it was time to learn to be the songwriter he had always wanted to be. He spent six months woodshedding, consulting with Nashville songwriters as he honed his craft. “I’m working as hard as I can to learn it,” he said in an interview.

It worked. In 1983 Dan released Rebel Heart, which featured the single “God Must Be a Cowboy,” a sentimental song he had written one day on a drive from Midland to Rankin to visit his father. “There’s nothing out there but God,” Dan explained to a journalist. It went to number 10 on the Billboard Country chart in 1984. Over the next year he had three more top ten hits, and then he really hit his stride: Between 1985 and 1990 he had an astonishing eleven number one country songs, most of them old-fashioned ballads that he wrote or cowrote. Dan often found himself pulling up his West Texas memories for songs such as “Everything That Glitters (Is Not Gold),” his number one hit based on a story his grandmother told him about a woman leaving her husband in Iraan.

The two brothers returned occasionally to Rankin to visit their father, who had retired in 1969 and lived with his mother, Cora, in the same house the boys had grown up in. Wayland was stooped and moved slowly—he’d lost a toe to gangrene, and his foot hurt constantly. He spent his time taking care of Cora, now an eccentric woman who wore a sunbonnet that hid her face and an old-fashioned long dress that covered her from neck to ankle. Neighbors would watch her walk around the yard smashing ants with a ball peen hammer.

Wayland told Jim he hadn’t played music much since Jim had moved to L.A. in 1958. “When you left,” he said, “the music died.” Still, sometimes he and his boys would pull out their guitars and play a few of the old songs.

Wayland rarely spoke with Jim about his music, though Jim had written a song called “Wayland the Rabbit,” which appeared on Seals and Crofts’s 1975 album I’ll Play for You. The song was a tribute from a son to a father: “I love Wayland because he’s strong,” sang Jim, “and I love him because he’s weak.” Wayland never talked to Jim about the song, though he once told Dan that he didn’t like the suggestion that he might be fragile. Wayland also told Dan that Jim’s music was the only music he’d ever heard that made him feel happy and sad at the same time.

Wayland wasn’t shy about telling others about his sons and their music. “He was very proud of those boys,” said Edra Owens, who still lives in Rankin. “Every time I’d see him in the grocery store, he’d be showing pictures of Jim or Dan to people. ‘That’s my son!’ he’d say.”

Toward the end, when their dad was in the hospital, the two visited Iraan and drove to the site of the old Shell Oil camp, where their house had been. They tried to picture the way it was forty years before, but everything was gone now. Wayland died in 1992, and Jim and Dan went to the funeral, the last time they were in Rankin together.

Dan’s career began to wind down after his last hit, though he kept on recording and touring. In 2003 he invited Jim to join him onstage at the Grand Ole Opry, in Nashville. Jim was wary; he thought no one in Nashville would want to hear the songs of a pop artist. But members of the audience jumped out of their seats when the opening notes of “Summer Breeze” sounded, and they stayed standing through “Diamond Girl,” singing along with the words. The songs had become classics.

After the show, Jim got to meet some of his childhood idols, such as Les Paul and Roy Acuff. And the brothers decided that, after more than fifty years, it was time to get the Seals family band back together again—and take their show on the road. Over the next four years, under the name Seals & Seals, they did almost two hundred shows in a group that included Jim’s sons Sutherland and Joshua on guitar and bass. “Jim, I’m having the most fun I’ve ever had in my whole life,” Dan kept telling his brother. “This is just so much fun.” Both men kept thinking of their father and how much it would have meant for him to see them together onstage. In 2009, two years after their last performance, Dan died of lymphoma at age 61.

These days, Jim and Ruby divide their time between Costa Rica and Hendersonville, Tennessee, just outside Nashville. Jim had a stroke in 2017 and can’t play music anymore, but he paints still lifes in the style of Monet and travels. He also hangs out with his half brother, Eddie, who moved to Nashville in 1968 and retired from the music business twenty years later. In fact, Nashville has been home to a crowd of Seals family musicians, including Jim and Dan’s uncle Chuck Seals (who cowrote the Ray Price hit “Crazy Arms”) and cousins Troy Seals (who cowrote “Seven Spanish Angels,” which Ray Charles and Willie Nelson took to the top of the country charts in 1985), Brady Seals (who played with the popular band Little Texas), and Johnny Duncan (who sang several country hits, including “Thinkin’ of a Rendezvous,” which topped the Billboard Country chart in 1978).

Dash and his second wife, Louise, live on a hilltop ranch near Johnson City, watching over several Egyptian Arabian horses and a herd of alpacas. They moved there in 2013, five miles from the cattle ranch that his great-grandfather ran in the nineteenth century. Dash recently spent time in the hospital for atrial fibrillation and doesn’t play music much either, though he still likes to pull out one of his old mandolins and finger the fretboard. He talks with Jim about once a month. As for John Ford Coley, he eventually gave up on acting, though he still performs occasionally.

Today, if you stop in Rankin, you can visit the town’s museum, which is located on the first two floors of the grand old Yates Hotel, built in 1927 at the height of the first oil boom and then closed in 1964. It’s the kind of place where, if you show up outside normal visiting hours (Monday and Tuesday, 9 a.m. to noon), you can call the number on the sign in the window and one of the volunteers will come over and give you a tour. The museum has an extensive collection of local artifacts: an antique organ, a variety of Rankin High School Red Devils pennants, and displays devoted to the local dentist’s awls and picks and the patches and merit badges earned by the Concho Valley Boy Scout troop.

The museum has also been involved in preserving the contents of the Seals family home, which has been deserted since 1992 and is now owned by the city. This past summer, volunteers began transporting some of the house’s furniture to the museum, and this fall workers set up a new exhibit on the second floor: a re-creation of the living room where the Seals family once gathered to play music all those years ago. The room has the austere look of that era: a couple of shabby chairs, a wood-burning stove, a scratched-up dining room table. Spread over the table is a collection of LPs and eight-track tapes that contain music made by Jim and Dan, and framed on the wall is a yellowed newspaper clipping of a 1986 story on Wayland; “Successful Sons Make Up For Hard Life,” reads the headline.

More than anyone, Wayland knew that his boys had to grow up and move far away from this room to find success. It was only then that Jim and Dan could look back at the hardscrabble life they had all known and see it differently than they had decades earlier—as something they could think of fondly, and sing about softly.

This article originally appeared in the February 2020 issue of Texas Monthly with the headline “Summer Breeze.” Subscribe today.

Editor’s note: Late in the reporting of this piece, the Rankin Museum closed for repairs. It is expected to reopen in March.