Writer, photographer, publisher, and champion of Texas culture Bill Wittliff died last week at the age of 79. He was laid to rest Thursday at a small family service at the Texas State Cemetery in Austin. (A public celebration of his life is being planned, but no date for the event has yet been announced.) Wittliff is such a shining light in our state’s literary and artistic firmament that we thought publishing just one remembrance of his life wasn’t nearly enough, as beautifully written as John Spong’s tribute was. We reached out to a few of his friends and colleagues, as well as Texas Monthly staffers past and present, seeking their personal recollections of the man. No doubt these represent just a tiny sampling of the many, many lives he touched.

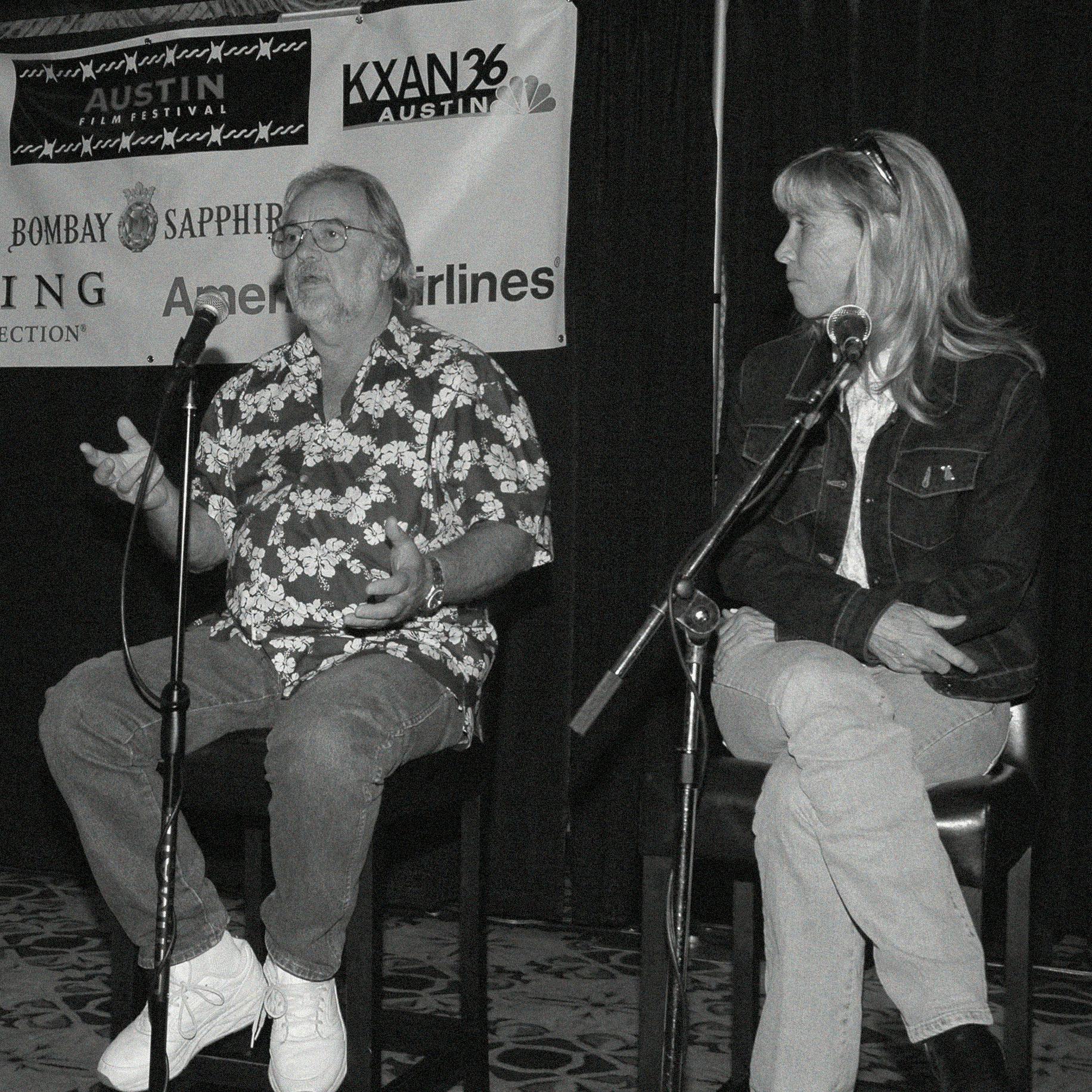

Barbara Morgan

Austin Film Festival executive director

An avid collector of art, artists, and history, Bill Wittliff was himself a collection of perpetual creativity, storytelling, and raw talent. He managed to spread these innate gifts across numerous art forms—novels, films, photographs—while finding unique ways to explore this world and the next, bridging lessons of the past with inspirations for tomorrow.

Perhaps his greatest superpower was his storytelling ability. Bill was a masterful teacher and orator, his stories infused with equal parts history, humanity, and magic. He could see into your soul and coax your own gifts out into the open, spreading creativity like a wild campfire—turning whispers into howls, ideas into masterpieces.

Centuries ago, we would have called Bill a shaman, one who teaches and influences, someone connected to the spirit world. Art was his portal. So often I heard him talk about writing as a sacred calling, something he channeled from the beyond. He believed it was the job of storytellers to point the way for the rest of us, and he led the way as diligently as he did effortlessly.

Since Bill’s passing, I’ve heard from so many people how moved they were by their relationships with him. Even if their interactions were few, Bill’s impact was plentiful. He made you feel seen and heard because he, in fact, could truly see you and hear you. Through the lives he touched, his own legacy ripples skyward, like embers from the campfires he so preciously tended.

My personal experiences with Bill spanned decades and were both personal and professional. He was a friend in its truest form, and he taught me how to once again believe in a sense of wonder I thought had been forever abandoned to my childhood. His wisdom, encouragement, and guileless faith in me were contagious. I always left his presence in a cloud of enchantment, something I’m certain wasn’t unique to our relationship.

There are too many memorable moments with Bill to recount, but there was a particular period of time that gave me a raw glimpse into his heart and soul. In the late nineties, he had been tasked with adapting the Stephen Ambrose best-seller Undaunted Courage into a miniseries. The story, if you recall, was fascinating—beckoning an otherworldly and wild sense of adventure through the eyes of Captain Meriwether Lewis. It became one of my favorite pastimes, and now one of my most treasured memories, to stop by Bill’s encampment on Baylor Street and listen to him deconstruct and reassemble this mighty, literary journey for the screen.

Of course, who else but the man who incarnated Lonesome Dove could do the task justice, reviving these ancient characters with layers of humanity, idiosyncrasies, flaws and all. For just as Bill could see into the depths of those who had the pleasure of knowing him, he was equally connected to the characters he created. He didn’t just study them; he channeled them. Bill spoke about this great expedition as if he had been on the journey himself, so moved by its triumphs and misfortunes, so in tune with its experiences of joy and pain. I imagined this is how it had been with Gus and Call, too, and that the dust of that small Texan border town gathered beneath Bill’s typewriter.

After reading his script for Undaunted Courage, it saddened me greatly when the project didn’t get made. I took solace, however, in the incredible opportunity to see a master at work. With firsthand knowledge of how the film industry is riddled with a graveyard of stories-that-could-have-been, I know how lucky we are to have received other projects of Bill’s.

From a film repertoire that has made me weep on many occasions, to an arts archive chock-full of gems, Bill spent his life creating more life. While we’ve lost a remarkable man in Bill Wittliff, it’s through these creations that his heart and soul live on, doing what they’ve always done best: inspiring us to believe in magic once more.

Anne Rapp

Screenwriter and Script Supervisor

A couple of years ago, I moved into a new house in Austin. Since I’ve made about a thousand moves in my lifetime, the transition to my new digs went like clockwork. Within a week, I had settled in nicely, and it looked as if I had lived in the place for years. A good friend, Connie Todd, came over for a glass of wine, and she gave me the thumbs up on the placement of all the furniture and wall hangings—except for one thing. She was disturbed that I had my two horseshoes hanging over the doorways with the open side down, rather than up.

I’ve had these two horseshoes for years. They came from my granddaddy’s barn, and they’ve hung over many, many doorways, always open side down. I know there is an ongoing, universal controversy about this. Some people believe you must hang horseshoes the way I do so that the good luck flows down upon everyone who walks through your door. Other people believe you must hang them open side up so it can collect the luck and hold it for you and your loved ones. I have always considered myself a lucky person—luck seems to come my way naturally—so I just assumed mine were hung correctly. But Connie was not convinced. We came to the conclusion that I needed to ask Señor Wittliff immediately. Connie knew Bill and his special mystical powers better than anyone, and she assured me he would guide the way.

The next day I went over to see Bill in his office. I explained my dilemma and asked what I should do. I wanted to know if flipping the horseshoes would change my luck for the even-better or if it might backfire on me and result in the opposite. I did admit that my luck had not been quite as good the last few years as it had been in earlier years. But that, overall, I had lived a life of good fortune.

Bill pondered this for a long moment. Then he looked at me with both compassion and confidence. He said, “Oh, dear cowgirl, surely you were born under a pointing-down horseshoe, and that’s why you’ve been so lucky for so long. But luck can sometimes run down to a trickle, and you need to fill the horseshoe up again. I urge you to turn that horseshoe open end up, to do that. But only if you believe it works. Because nothing—nothing!—works without belief. Please believe me.”

Nothing works without belief.

Just looking into his eyes that day, I instantly believed it one hundred percent—because he had said it. I jumped up out of the chair and told him I needed to race home immediately and flip those horseshoes. As I was running out the door, he said, “Where is this new home of yours?” I pointed and said, “Oh, just right over there, in this neighborhood. I could hit your office with a 3-wood.” Bill said, “What’s a 3-wood?”

These are the magical moments I will always remember when I think of Bill. His wisdom, his humor, and the truth. One of the luckiest things that ever happened to me was getting to know him and calling him my friend.

Till we meet again, amigo, buena suerte!

Stephen Harrigan

Author, historian, and Texas Monthly writer-at-large

In the early eighties, I was a young writer desperately trying to finish a second novel. With three children noisily occupying every square foot of our house, and with laptop computers and coffeehouses still so undreamed-of they didn’t even count as fantasies, my most pressing need was a place to work.

As was to be the case so many times in my career, Bill Wittliff came to my rescue. He offered me the rent-free use of a room just above his own office in the building that he owned on the corner of Baylor and Sixth streets in Austin, just down the street from the Treaty Oak, the tree that legend maintains was the site where Stephen F. Austin once opened peace talks with the Comanches. Bill’s old stone house was itself historic, built in the nineteenth century and rumored to be haunted by everyone from a Civil War widow to William Sydney Porter, the short story writer better known as O. Henry.

I never encountered any ghosts while I worked there, though of course Bill did all the time. He was proud of being “spooky.” He would hear or see phantasms while he worked in his darkroom upstairs, or in the first-floor office where he wrote his increasingly famous screenplays by hand on loose-leaf notebook paper.

One day I was sitting in his office when he said, “Hey, put this on,” and plunked an oversize cowboy hat on top of my head. Then he took a picture. What emerged later from his darkroom was the most ridiculous photo of me ever taken. The hat is so big it rests on the top rim of my giant eighties glasses. There’s a look on my face that might be inscrutable menace, or maybe blank despair, or probably just plain embarrassment.

This photo was recently unearthed, and to my mortification (but also with my wary blessings) the University of Texas Press used it as the cover of its Fall and Winter catalog, in which my most recent book is featured. When Bill heard about this, he was so delighted he made a big print for me and prints for each of my children. And he didn’t stop there. A week before he died, he called me up and said he had made prints for my grandchildren.

The last time I saw him, which was Thursday, June 6, I stopped by the house on Baylor Street—the place where thanks to Bill my writing career had been salvaged and sustained—to pick up the six new prints he had made. I said thank you and goodbye, not knowing it was the last time, not knowing I was carrying away his last gift to me. But I understand now, since this gift was for a generation just getting underway, that it might not have been such a stark goodbye. After all, Bill was completely at home in a spooky world where the dead interact with the living. My grandchildren will never meet Bill Wittliff, but whenever they look at that silly photo of me in the cowboy hat, they will know him.

Christian Wallace

Texas Monthly associate editor

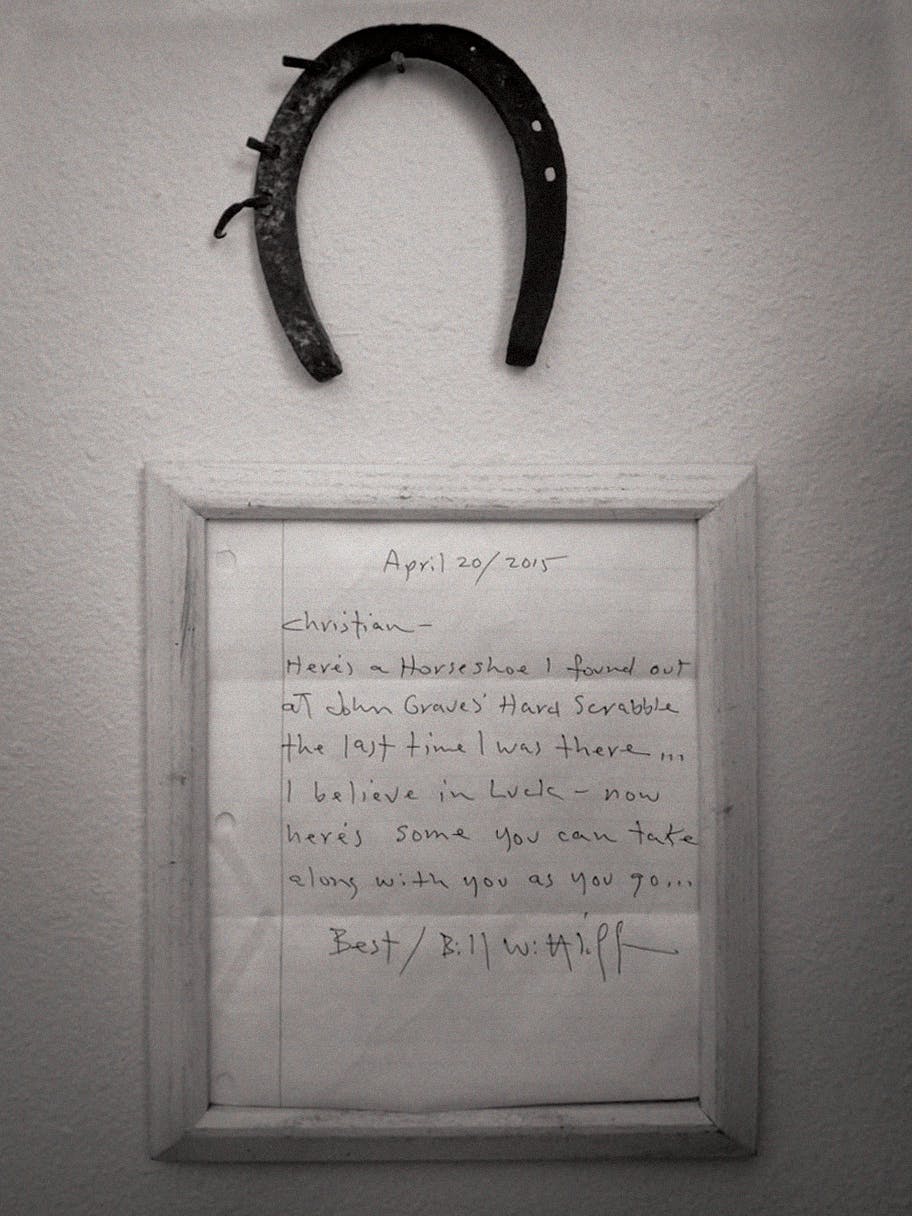

I only met Bill Wittliff once. We spoke at a reading at the Southwestern Writers Collection. During our brief conversation, he asked me what kind of writer I wanted to be. I pointed a thumb toward the nearby statue of John Graves. A few days later, I got a call from an administrator at the Wittliff Collections. She said they had a package for me. I went by and picked up a manila envelope with my name scrawled across the front. Inside was a rusted horseshoe and a letter.

Christian—

Here’s a horseshoe I found out at John Graves’ Hard Scrabble the last I was there… I believe in Luck—now here’s some you can take along with you as you go… Best / Bill Wittliff

It was one of the kindest and most unexpected gifts I’ve ever received. For a Texas literature fanboy, it was also one of the coolest. I wrote Bill, thanking him, and he told me to “pass it on when you’re an Old Fart.”

As someone who went to Texas State, I cannot overstate how much it meant to have the Wittliff on campus. I attended my first poetry reading there, met some of my favorite authors, and spent a lot of time browsing the exhibits. The Wittliff made me feel like the work I loved—Sandra Cisneros, Larry L. King, Graves, Sam Shepard, Willie, McMurtry—had lasting literary value, that those writers were just as important as the Big Names at the Harry Ransom Center at UT. The collection gave gravity, context, and meaning to the work that I hoped to do. That was inspiring to an eighteen-year-old wannabe writer from West Texas. It still is.

Years after our meeting, when I published my first Texas Monthly cover story, I sent Bill a copy of the issue and told him thanks for the luck. I wish I would have told him that I was grateful to him for so much more.

Sarah Bird

Novelist and Texas Monthly writer-at-large

For reasons that can only be explained by generosity and a gambler’s instinct to play the long odds, Bill called me in 1993 to talk about the possibility of my writing an episode for his television series, Ned Blessing. I was a definite long shot, since my only screenwriting experience, at that point, was adapting my second novel for a fabulously forgettable film.

I was already nervous about meeting the legendary man when my babysitter phoned ten minutes before I was supposed to leave to tell me that she had cramps and wasn’t coming to look after my son, Gabriel.

Certain that my lack of TV experience—combined with the super-professional move of bringing a three-year-old to what was, essentially, a job interview—would knock me out of the running, my little assistant and I headed out.

Bill being Bill, he was delighted by the surprise addition. As an enchanted boy explored the priceless Western artifacts—“Look, Mom, cowboy stuff!”—that filled his office, Bill, always the teacher able to make a student feel as if nothing were out of reach, broke down TV writing for me.

“Sarah,” he explained, “The only difference is that, instead of three acts like a feature, an hour of TV has seven acts. For the commercial breaks. And you have to keep the audience coming back.” He gave some cliff-hanging examples. “Something surprising happens. A secret is revealed. A tomahawk flies through the air. A stranger rides into town. A—”

“A dinosaur comes to town!” Gabriel burst out.

Bill, acting like my son was the one in that room who had two Emmy nominations, widened his eyes, and asked, “A dinosaur? What kind?”

“A T. rex.”

I don’t recall what other dinosaurs were discussed. (Probably the iguanodon, as the iguanodon was “the second best of all the dinosaurs” in Gabriel’s accounting.) Nor do I remember when Bill told me I had the job. What does remain in my memory of that day is his kindness.

And what I wish for is what we all wish for when someone is taken too suddenly. I wish I’d had a chance to thank him and to tell him how much that day, so long ago now, and all the gracious moments that followed, meant to me.

Skip Hollandsworth

Texas Monthly executive editor

What I remember about Wittliff was his graciousness. When I was assigned to write a story on him for Texas Monthly, I was so in awe of him and the crowd he hung out with that I didn’t know what to say. But he immediately made me feel part of the crowd, going so far as to show me a screenplay he was working on, asking me whether a line he had written sounded right—or should he change it? I’m not sure I had even seen a screenplay before that moment. I said the line read fine to me. He roared with laughter and said, “Oh, come on, you know it’s terrible.”

Lawrence Wright

Journalist, playwright, and former Texas Monthly writer

Some of my favorite journal entries regarding Bill:

June 11, 1997

Went by Bill Wittliff’s office to drop off the plans for Plaza Saltillo, where CAST [Capital Area Statues] may try to place another statue. He was telling me about a scene he was working on for his Lewis and Clark miniseries, where Clark meets Daniel Boone—an entirely fictitious event. He spoke the scene from memory—it was a wonderful scene, where Boone takes Clark to an Indian cave to see the pictographs and warns him that Clark is likely to live the rest of his life “robbing the world of its mystery, as I have.”

I asked Bill how he loosened up his mind so that he could write impressionistically. “Pray,” he said. “At night, I pray and think about the scene I’m about to write, and I let my mind work on it while I’m asleep. Then in the morning, oftentimes, it just comes.”

June 24, 2008

Bill told a story about going to his own real father’s funeral (he had rarely met him). Bill and his brother took a bus to Corpus Christi. The father, a drunk, had bled to death from an old World War II injury in his side that never healed. There was some chapel out on Ocean Drive that had a tin roof. There were two chairs up front for the boys. People were upset because they were running late. The pastor got started, and he kept forgetting the father’s name—he was fishing through his pockets looking for a reminder. “He was only forty-three—and untimely death,” the pastor remarked. “Forty-three. That was the age of my wife. Only forty-three! And the Lord plucked her, like a berry from a bush.” The pastor pushed his glasses up on his head and began to sob. Then his glasses fell down and landed on his nose all askew, and the pastor forged ahead with his inane sermon. “My brother was crying, and I was laughing,” Bill recalled. “But from the rear, it looked the same.” He shrugged his shoulders up and down, then said fondly, “Like a berry from a bush!”

November 9, 2011

Big night for CAST. We had an informal unveiling of “Willie” at Troublemaker Studios. Willie came, in his black hat and braids. He was gracious and seemed a bit overwhelmed. I said in my remarks that all of our previous statues had been of people who were long and safely dead, so I hoped he behaved himself from now on.

After we pulled the tarp—actually, a parachute—Willie and Bill Wittliff and I were admiring the piece, and Bill explained that what we liked about the piece was its engagement with the audience. “People will come to you,” he said.

“And ask for advice,” Willie said.

“Little children will touch your knee and seek your counsel.”

“Do what I say and not what I do,” Willie said.

November 16, 2011

Last Saturday, we went to the Wittliffs’ for a dinner for Bill Broyles, who was in town to emcee the gala for the Wittliff collection the following night. Lots of old (very old) friends and eminences—Gary Cartwright, Jerry Jeff Walker, Victor Emanuel. The new director of the collection, David Coleman, was there. In front of Bill Wittliff, I joked that, whatever he needed, just make a list, and Bill would be happy to write a check. Bill laughed and recalled that, during the last fundraiser, G.W. Bailey had read a letter from Larry L. King to Bud Shrake, in which he remarked that getting money out of Wittliff was about as likely as getting a blow job from John Wayne.

Bill Broyles

Journalist, screenwriter, and founding editor of Texas Monthly

When Mike Levy and I were starting Texas Monthly back in 1972, I went to visit Billy (as he was called then) at the Encino Press, then over in South Austin. He told me he didn’t know any more about publishing than I knew about journalism but that hadn’t stopped him, and it shouldn’t stop me. He said that, for a storyteller, Texas was a treasure that never stopped giving. He gave me a copy of In a Narrow Grave by Larry McMurtry and said he’d caught hell from the then-Texas Literary Establishment (which it savaged) for publishing it, but he’d done it because it was honest and true and great writing, and I should seek to do the same. He said it had one foot in Old Texas and the other in New and that I could have a damn fun time exploring both.

Bill taught me to love and nurture talent and just enough of his poker secrets that I could almost, but not quite, win in our monthly poker games that lasted for decades. He was my mentor and friend and inspiration for almost fifty years. He was a Renaissance talent as a writer, photographer, and filmmaker. But, beyond all that, he was a lifelong supporter of countless Texas writers, photographers, filmmakers, and artists. Beginning with the Encino Press and continuing through the Wittliff Collection at Texas State, Bill and his wife Sally nourished, encouraged, and celebrated generations of us. He was the hub. We are all the spokes. He was rooted in tradition and embraced innovation. He had a stubborn, mystical belief in the creative process and an unerring eye for the beautiful and the true, and he could find a story in just about anything. He was Old Texas and New Texas too. He was a poker-playing, horse-trading boy from Blanco, and he remained that joyful Blanco Boy his entire life.

Wes Ferguson

Texas Monthly writer-at-large

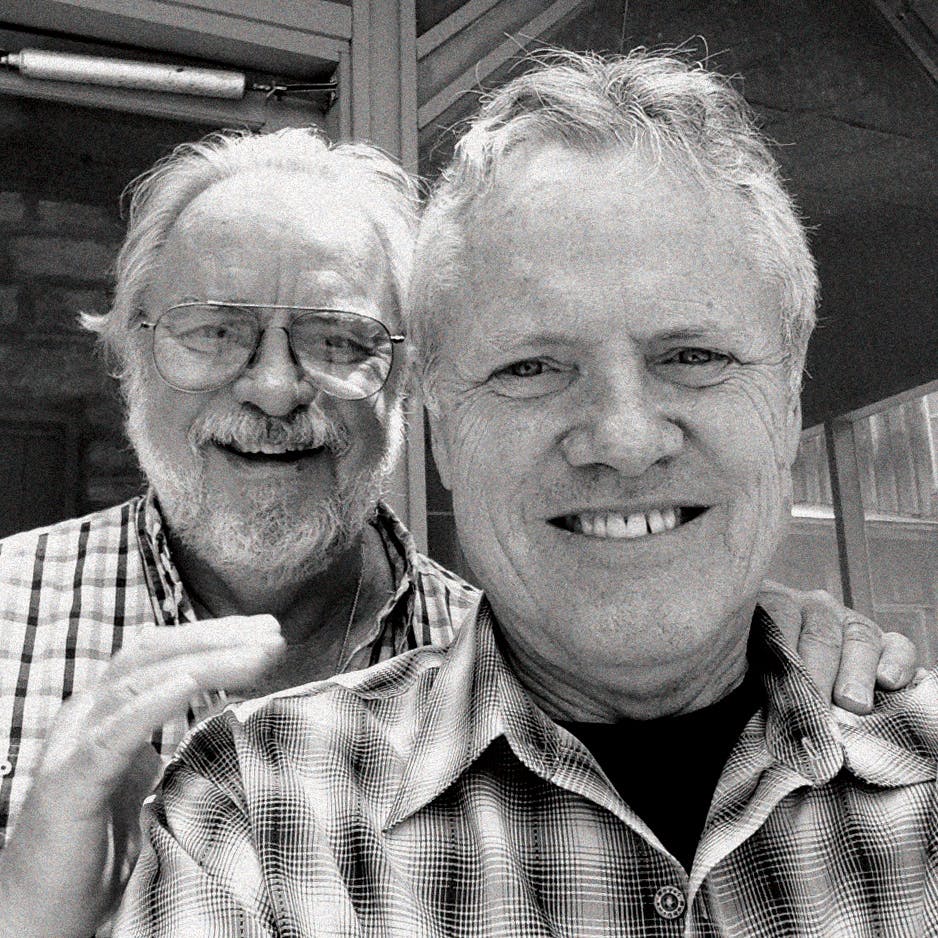

For more than half his life, Bill Wittliff made his headquarters in a handsome Victorian house just west of downtown Austin, where an upstairs room was said to be haunted by the friendly ghost of former tenant William Sydney Porter—better known by his pen name, O. Henry. The apparition was far from Wittliff’s only famous visitor.

Like many of the fine tributes that have poured in since his death on June 9, Wittliff’s obituary describes a “procession of movie stars and literary and music legends” who routinely dropped by, often unannounced, to see the renowned storyteller, photographer, collector, and visionary cofounder of the Wittliff Collections in San Marcos, the finest repository of our region’s literature and photography.

The obituary goes on to note that, “It didn’t matter to Bill if you were famous or unknown, if you were serious about your craft, he was serious about you and would be your friend for life.”

About a year and a half ago, I joined the parade of unknowns at Wittliff’s door. Not to overstate things—I mostly lucked into spending a little time with him via my friendship with his assistant, photographer Joe Pat Davis. With his tousled white hair and beard, Wittliff struck me as a living link to previous generations of Texas greats like J. Frank Dobie and John Graves, and while he’d accomplished pretty much everything in life, he still had a humble and disarming way of inspiring me to pursue my own work. “I think this is important for your career and for your art,” he’d say, encouraging me to meet up with a creative luminary or read a particular book or look at a body of photographs. After our first meeting, I dreamed up additional reasons to revisit Wittliff’s office, a Texana hoarder’s paradise of precariously stacked books and box upon box of fine-art photographic prints. Rolls of film gathered dust on the fireplace mantel behind a wooden desk, itself buried under papers, books, and manuscripts. Filling the remainder of the room, it seemed, were stacks of framed prints awaiting nonexistent wall space.

You had to be careful where you walked and where you sat, with Wittliff and Davis juggling so many projects. There were public sculptures to commission and arcane photographic processes to attempt. One morning, Davis might be transcribing the handwritten pages of Wittliff’s latest writing project; some other afternoon, he’d be upstairs with O. Henry’s ghost, scanning black and white photos Wittliff had acquired of Don Pedrito Jaramillo, the South Texas folk healer who died in 1907.

Like the late curandero, Wittliff was known to have a mystical streak. He often wore a necklace adorned with a milagro of Don Pedrito, and he lived by the motto “La Vida Brinca,” literally translated as “Life Jumps.” As the obit puts it, “La Vida Brinca meant that unpredictability and surprise—of both the welcome and grievous variety—were not just givens of human existence but drivers of human wonder and creativity.”

No one was more attuned to life’s jumps than Bill Wittliff. It’s hard to imagine anyone leaving a more enduring imprint on Texas culture, creativity, and the procession of friends and admirers, both famous and unknown, who will miss him.

- More About:

- Books

- Stephen Harrigan

- Lawrence Wright

- Bill Wittliff

- Bill Broyles