It’s a deep, midnight-colored October evening in 1992. The first chill of autumn has arrived in Harlingen, bringing a reprieve from the summer heat that has lingered too long. Eight-year-old me pulls a dog-eared paperback from my backpack and I turn on the bedside lamp. The book’s edges have yellowed, but the pages inside remain creamy white. Flipping through it, I can smell decades of history—its stories told countless times on cool concrete porches or warm wooden rockers or over coffee-stained kitchen tables. I read the title out loud—Stories That Must Not Die. Ask anyone who went to elementary school in South Texas what Stories That Must Not Die is, and you’ll hear a variety of answers. To scholars, it’s a collection of folklore. To teachers, it’s a valuable bilingual teaching aid. To students and parents, though, it’s a treasure trove of the region’s best-known, most beloved tales.

There is a sophistication and poise in Stories That Must Not Die, a sort of straightforward beauty in each of the collected stories. Juan Sauvageau’s Spanish translations bear the hallmarks of border Spanish—the indigenous loanwords, the syntax, the same two-stepping cadences and rhythms that aren’t found anywhere else. Think of your grandmother sitting under a warm yellow bug light under the carport on a humid evening, sipping a cup of black coffee, speaking with all the gravitas of a courtroom deposition about the apparition of the infamous Woman in Black, or the devil in the Bluetown well on the way to Brownsville. Try not to scoff at the miraculous cures that Don Pedrito Jaramillo made in his clapboard cabin in Hebbronville, tenuous proof of faith in a faithless world. Try not to say a prayer when you hear thunder crack through the bluest sea breeze of a hot South Texas afternoon. These are all things I read in Stories That Must Not Die, and was moved by the singular resonance of their simplicity and bilingual elegance.

These ghost stories are not merely told to frighten children into behaving. They are the record of a collective memory marred by colonialism and intergenerational violence, a world of ranches and chaparral touched by fire from Mexican muskets and Texas Ranger pistols and lightning from above. And we would not have them had it not been for a French-Canadian man who came to be known as Juan Sauvageau.

Born in Québec, John James Sauveageau was the author of all four volumes of Stories That Must Not Die. He lived and worked in Mexico, France, Spain, and other parts of the United States before coming to South Texas sometime during the mid-20th century to teach at what is now Texas A&M–Kingsville. Intrigued by idiosyncratic Tejano culture, he visited ranches and towns from Laredo to Brownsville in search of folklore.

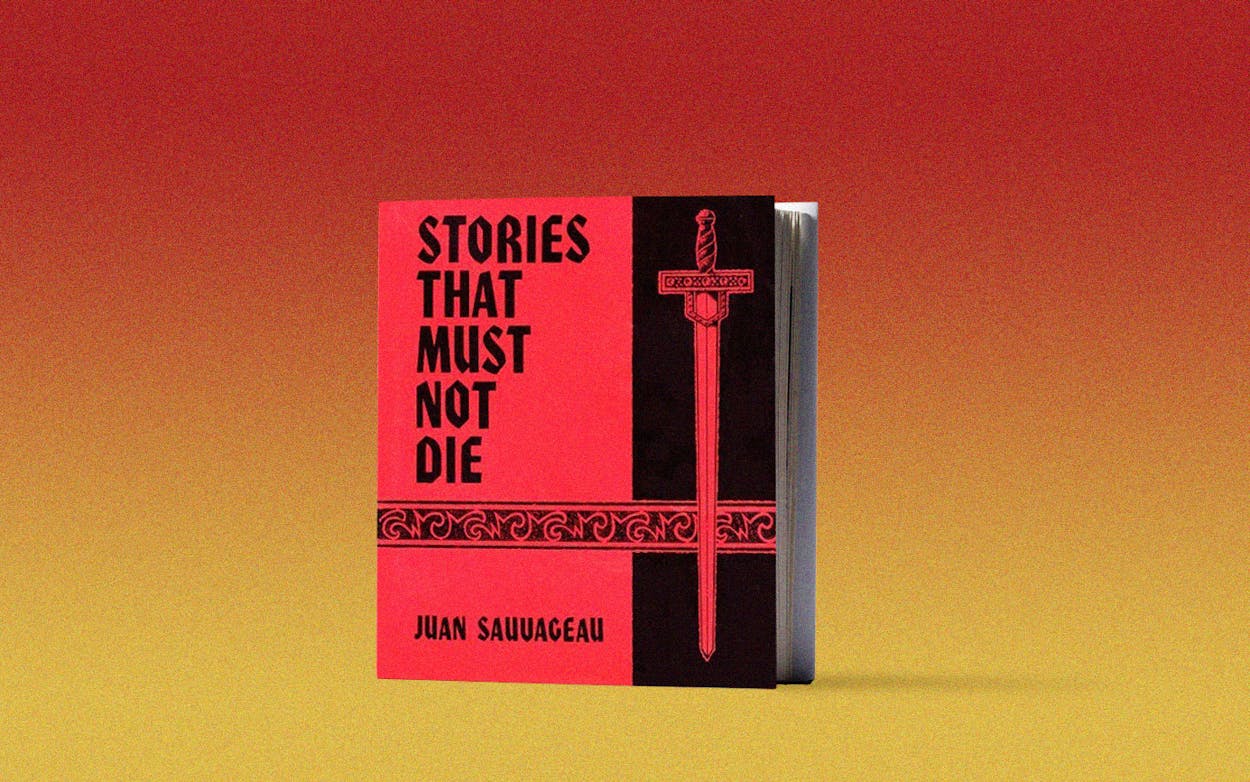

By the mid-1970s the tales he’d collected were showing up in local newspapers, all over the Rio Grande Valley. Sauvageau—who had changed his first name to Juan—had collected a handful of stories in Spanish, translated them into English, and published them in 1976. All four volumes have an eye-catching design: The titles appear in a chunky Roman font, accompanied by a drawing of a jeweled, hilted sword pointing downward. Roel Montalvo’s illustrations are loopy and true to their 1970s origin (one of the depicted characters resembles Charles Bronson, helmet hair and all).

Sauvageau—who died in Meridian, Idaho in 2011—originally wrote Stories That Must Not Die with young readers in mind. Their entire purpose was to foster bilingual literacy and cultural understanding. At that point, very few people (Gloria Anzaldúa and Américo Paredes, for example) had tackled the torturous history of the Rio Grande Valley as a standalone subject. But Sauvageau carefully collected the stories and presented them in a storybook format, along with a word list and reading comprehension questions in both English and Spanish. Kids and teachers loved the stories for different reasons: teachers appreciated the folkloric tales’ educational impact, while scary story-loving kids ate up the accounts of ghostly weeping women, poor little naked birds, and vanishing hitchhikers–stories all situated in their own backyard.

But the real brilliance of Stories That Must Not Die lies in its matter-of-fact retellings of key moments in Tejano history. “Los Rinches,” for instance, is a half-true recounting of the Texas Rangers’ misdeeds in South Texas, which were only commemorated in recent years with a historical marker near Brownsville. Another tells the true tale of Gregorio Cortéz, whose exploits won him both the admiration and scorn of Texans north and south of the Nueces. Sauvageau carefully skirts controversy by glossing over some events, but otherwise correctly relays historical truths. For some Tejano kids like myself, these stories were the first time we’d been introduced to a history of our own people.

The book’s most famous tales have been inscribed in the memory of every Chicano child: Particularly that of La Llorona, who drowns her children in the Rio Grande (specifically in a place called “El Rincón del Diablo” in Laredo, “The Devil’s Corner”) because she cannot give them a better life. This version of the legend adopts a very American moral obsession with material security and happiness, and is markedly different than the more moralistic rendition in Mexico that reflects aspects of genocide. Another famous story, “The Handsome Stranger,” recounts how a spoiled, selfish girl disobeys her mother’s forbiddance to attend a dance and finds herself pulled into the arms of Satan himself in a horrifying whirl of sulphur and brimstone. Animal stories are included alongside the ghost stories, reflective of the ancient cultures of indigenous people on the lower border.

In their truest form, the stories preserved memories of a landscape punctuated with doubt and fear; the violence suffered by Leonora Rodríguez de Ramos, the ‘Woman in Black’ seen traversing the intersection of Highway 281 and Farm-to-Market road 141 near Ben Bolt, is both an historical fact and a moral admonishment. Her hanging (which occurred before statehood) is a bone-chilling reminder of the scourge of domestic violence that can exist within Hispanic families.

I often think of that cool Friday night when I read my first volume of Stories That Must Not Die, cover to cover. I read the other three volumes within weeks and acquainted myself with their facts as if I were investigating a crime scene. At school, details were embellished among children who’d heard them; the stories mutated into the tallest of tales. Adults were consulted to verify their accuracy. All four volumes were perpetually checked out by fascinated schoolchildren all school year long .

Sauvageau’s work is hard to find nowadays though—the forty stories have never been collected into one single volume, and aside from a few cursory reprints of individual stories with illustrations by regional artists like Noé Vela and Jessica P. González, a complete Stories That Must Not Die remains elusive. Their presence in the minds of Tejanos as a source of literary inspiration is impressive: taken as a whole, they represent an important South Texan variety of Southern Gothic literature. Countless writers (like Donna native and writer David Bowles) have cited Sauvageau’s work as an important contributor to the literary heritage of Texas. I myself owe a great deal of debt as a writer to Stories That Must Not Die, both as an appreciator of Texas history, and as a writer of fiction centered on the border and the people who live there.

In the hearts and minds of many Tejanos, however, these books remain enshrined as a quintessential goth essential. Like all things from South Texas, these cherished volumes of folklore deserve greater attention—a rediscovery—especially now as Texas comes to terms with the violent and vengeful ghosts of its not-too-distant past. As an adult I can see the animosity that belied the supposedly harmonious world of the Rio Grande Valley. I can see ruthless Texas Rangers, heartless Mexican brigands, powerless farm laborers, and unscrupulous land barons. I can see the wide plains of the border spread out like a tablecloth—a battlefield, a contest of wills—between traditional and emerging identities, touched by steel and born in blood and fire, separated by a stinking river.

When I read Stories That Must Not Die, I am reminded of the perennial tragedy and heartbreak that marked the lives of people who lived here, how close they were to losing it all, how unfortunate were those who did. Their legacy is immortalized in these fables, legends, ghost stories. For nearly five decades these tales have lingered with anyone lucky enough to read them—and they will continue to for years to come. In fifty years’ time there may be more Stories That Must Not Die that will both haunt and inspire our children. It will be up to us to explain, in our own way, why those stories matter.

- More About:

- Books