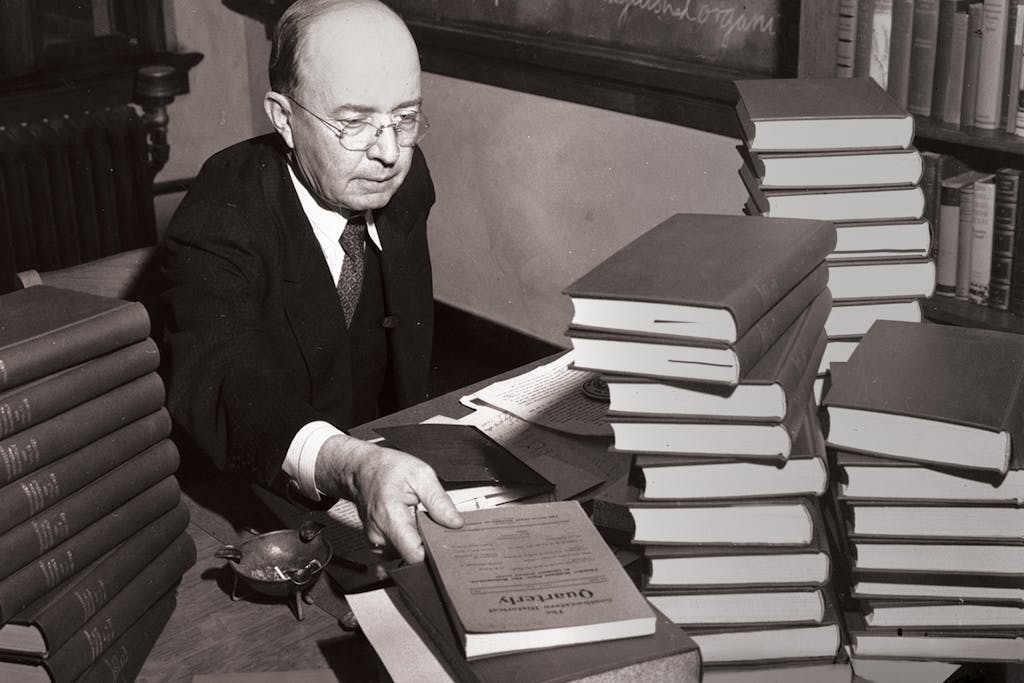

While working in the archives at the Dolph Briscoe Center for American History at the University of Texas at Austin, the historian Michael Collins came across what he describes, somewhat hyperbolically, as “a buried treasure—pure gold, at least in a figurative sense.” It was the unfinished autobiography of Walter Prescott Webb, perhaps the most famous historian the Lone Star State has ever produced. Webb drafted the manuscript in his mid-fifties while spending the 1942–1943 academic year at the University of Oxford as the Harmsworth Visiting Professor of American History and then apparently set it aside. Though Collins, as he began reading the narrative in the summer of 2008, anticipated “the stale chronicle of a stodgy, pedantic old professor’s life and academic career,” he concluded instead that the 230-page memoir was a “masterful piece of literature,” a real-life bildungsroman mixing profound introspection and self-deprecating humor.

In fact, what Webb titled “The Texan’s Story” had been lying in plain sight for decades—the treasure hadn’t been buried all that deep. Researchers, Collins among them, had known of the manuscript for years; some had previously mined it for insights into Webb’s life and work.

And yet Collins—a professor emeritus of history at Midwestern State University, in Wichita Falls—has rendered a great service in editing and annotating Webb’s memoir for publication in book form as A Texan’s Story: The Autobiography of Walter Prescott Webb (University of Oklahoma Press). It’s an engrossing portrait of the scholar as a young (and middle-aged) man, and it reveals how Webb’s lived experience indelibly informed his two best-known books, The Great Plains and The Texas Rangers—for the better and, in many ways, for the worse.

Walter Prescott Webb’s ascent to the highest ranks of his profession was nothing short of miraculous. He was born in 1888 in Panola County, in East Texas, to parents who had emigrated from Mississippi. The family relocated several times throughout Webb’s boyhood before settling in the Cross Timbers, a hardscrabble region about eighty miles west of Fort Worth. This final move constituted “a sharp break,” according to Webb, “because it carried us from the old America into the new”—that is, from the settled country of the Deep South to the wide-open spaces of the West. Webb’s father established a homestead in Stephens County and taught school.

As a close friend of Webb’s, the folklorist J. Frank Dobie, once observed, “Few other men of his stature and intellectual power experienced so intimately the choke of poverty.” Young Webb helped out by plowing fields and picking cotton. Reflecting on the tedium and misery of his early years, he wrote acidly in his memoir, “Don’t talk to me about the joys of childhood. They exist largely in the minds of adults.”

His life might have turned out much like his father’s if not for the salvation, in Webb’s words, of “a thin dime” he coaxed from his mother for a subscription to the Sunny South, a literary magazine published in Atlanta. Vexed by his dim prospects, the teenage Webb sent a plaintive letter to the editor in early 1904 expressing his wish to get an education and become a writer. His missive, which was printed in the journal’s “gossip corner,” was spotted by William Ellery Hinds, a Brooklyn-based toy manufacturer, who wrote Webb to offer encouragement, insisting that “there is no such thing as fail in the lexicon of youth” and volunteering to send the boy some additional reading material.

Thus began an intermittent correspondence that lasted until Hinds’s death, eight years later; by then, his inspiration and financial support had spurred Webb to matriculate at UT. Webb—who never met his benefactor but forever kept that first letter and even the envelope it came in—dedicated The Texas Rangers to him. Years later, in an article for Harper’s Magazine, he described Hinds’s generosity as “the nearest thing to applied Christianity that I know.”

Austin’s bright lights and city streets dazzled Webb upon his arrival at UT in September 1909, at the age of 21, inspiring vivid memories that, more than three decades later, flickered in his mind, he recalls, “like pictures on a screen.” His ambitions, however, were quickly dashed by poor academic preparation. After nearly receiving a failing grade on a paper, Webb became “so word conscious, so comma blind, and so sentence-structure minded” that for a time he gave up writing altogether. He was far happier under the tutelage of the social scientist Lindley Miller Keasbey, from whom Webb “learned to examine the relationship between the environment and human culture,” a skill that became a hallmark of his scholarship.

Webb earned his BA in 1915 and returned to UT three years later to teach in the department of history and begin graduate studies. After completing a master’s thesis on the Texas Rangers in 1920, Webb—bowing to pressure to seek “the accursed Ph.D.”—enrolled in a doctoral program at the University of Chicago in 1922, with his wife and young daughter in tow. But he failed his preliminary examinations—“the hardest blow I ever received,” which raised brief thoughts of suicide—and returned to Texas after a year, broke and broken.

In his presidential address to the American Historical Association in 1958, Webb said that he absorbed but one lesson from his embittering Chicago sojourn: “Don’t take an original idea into a graduate school,” lest academic convention impede its growth. The “original idea” in question had struck Webb shortly before he decamped for the Midwest, around the time he “became reconciled to the fact I had grown up on the frontier and that I could not rub off the evidence.” As he worked on some journalistic pieces about the Texas Rangers one rainy evening in February 1922, it dawned on him that it was the six-shooter—and not the long rifle, as previous scholars had insisted—that had facilitated Anglo conquest of the Great Plains, by allowing easy, rapid fire from horseback. That insight yielded others about how white pioneers, traveling westward across the 98th meridian—just as his own family had done—adapted to their new environment through technology, including barbed wire (permitting fence construction despite the scarcity of timber) and the windmill (providing access to subsurface water for irrigation).

Webb’s concept of an “institutional fault [line]” running down the middle of the country survived his year of “educational outbreeding” in Chicago and became the central argument of his first book, The Great Plains. Published in 1931, it was greeted warmly in major newspapers, including the New York Times, which ran a rave review on the front page of its Sunday books section. Among the volume’s attributes, according to the critic, was its “abundant evidence of firsthand acquaintance with the conditions of Western life,” which was certainly true given the facts of Webb’s childhood.

Of those long-ago days, Webb recalled in his memoir, “Though the frontier was gone, if by that it is meant that the buffalo and the wild Indians were gone, the flavor and tang of it was all around. The ashes of its campfire were still warm, especially to a lively imagination.” The UT history department—where he had taught since his return from Illinois—accepted The Great Plains as his doctoral dissertation and awarded him a PhD, in 1932.

Nearly a century after its publication, The Great Plains remains relevant, above all, for its contention that the region (and the wider trans–Mississippi West) was defined by its aridity. Nevertheless, any college professor assigning it today might be tempted to stick a warning label on the cover to acknowledge the book’s shortcomings, among them its reductive environmental determinism and penchant for sweeping generalization.

As it happens, these were two of the primary complaints that emerged at a conference dedicated to the book held at a luxury resort in Pennsylvania in September 1939. Webb was infuriated by the scope and tone of a peer’s stinging assessment (even as other scholars in attendance hailed his achievement) and insisted, “I would not prostitute The Great Plains by accepting [the critique] as an appraisal.” Given the significance of the episode—which, according to one scholar, divided the community of American historians for years—it is surprising that it receives only passing mention in A Texan’s Story.

One of the critic’s more muted points—namely, that Webb failed to consider how more generous treatment of Native peoples might have smoothed westward Anglo migration—may resonate even more with the modern reader, who will wince at the casual racism that suffuses The Great Plains. Take, for instance, the infamous passage in which Webb likens the blood of “sedentary” Pueblo Indians to “ditch water.” Caveat lector.

In contrast to his first book, Webb’s sophomore effort—The Texas Rangers: A Century of Frontier Defense, published in 1935—is unlikely to find a home on many syllabi. Beyond its unvarnished bigotry (far more pronounced than in The Great Plains), the volume reads like a lengthy series of colorful scenes drawn from the annals of the famed constabulary. Webb himself acknowledged the absence of a coherent through line and regarded the study as little more than “a competent journeyman’s job.”

Each of these principal defects grows from the same thorny root. Because Webb didn’t have the direct experience that had lent such immediacy to The Great Plains, he compensated by interviewing members of the force, including some of the veterans who had participated in the brutal campaigns against Native Americans and peoples of Mexican descent in the decades following the Civil War. He even took a three-week automobile tour of South Texas with a Ranger detachment, for which he received a commission (as well as “a cartridge belt and a forty-five calibre double-action Colt revolver”). This dearth of critical distance led Webb to imbibe his subjects’ prejudices and narrate their (often self-serving) tales with little context or analysis—a failing exacerbated by his lack of interest in the perspectives of the people on the receiving end of the Rangers’ violence (a flaw that Webb conceded late in life).

A Texan’s Story illuminates another key difference between the two books: Webb approached The Texas Rangers fueled by practical considerations rather than sheer intellectual curiosity. Not long after receiving his master’s, Webb had discovered that there was a market for popular writing about the Rangers when he was commissioned by the editor of the Dallas Morning News to write a series of illustrated articles about the group’s exploits; other opportunities soon followed. Thus alert to a commercial possibility, he timed the book’s release to coincide with the Rangers’ centennial, a strategy that—aided by the state’s own hundredth anniversary the following year—paid off handsomely when royalties quickly surpassed the generous advance he had received from his publisher, Houghton Mifflin.

Better yet for Webb, the firm sold the film rights for “a figure that required five digits to write,” which he notes with some satisfaction. Although he was irked not to receive an invitation to the movie’s Dallas premiere, he thought it was good entertainment, if suspect as history. Much the same could be said of the book on which it was (very loosely) based, even if for many readers the volume remains, as his friend Dobie described it, “the beginning, middle, and end of the subject.” In fact, it is mainly in recent years—with the publication of books like Benjamin Heber Johnson’s Revolution in Texas, Monica Muñoz Martinez’s The Injustice Never Leaves You, and Doug J. Swanson’s Cult of Glory—that a very different version of Ranger history has entered the broader consciousness.

While the unlikely course of Webb’s life and career unspools across the first four chapters of A Texan’s Story, in the fifth and final chapter he wraps up with a welter of thoughts on World War II (then raging right across the English Channel from his perch at Oxford), the perils of American isolationism, and his success in Austin real estate. And there ends his autobiography, a project to which he never returned before perishing in a car accident near Austin in March 1963, just shy of his seventy-fifth birthday. Collins speculates about why Webb abandoned the memoir, suggesting that life, professional obligations, or even campus politics intruded. Or, Collins muses, perhaps Webb became consumed with the completion of his most ambitious book, 1951’s The Great Frontier, in which he argued that the boom era of western expansion that began in 1492 had ended in the early twentieth century, with drastic global consequences. Or maybe he simply preferred to spend his time entertaining guests at Friday Mountain Ranch, his retreat southwest of Austin, whose frequent visitors included Dobie and the third member of their famed triumvirate, the naturalist Roy Bedichek.

Webb generally abided by the adage “Write what you know,” and what he knew best was the Anglo-Texan frontier experience of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Although he arrived on the scene near its end, he was close enough to the white settlers he considered the “first men” of the West Texas frontier that in his mind’s eye he could see these “real people,” as he called them, “those who were hunting buffalo, fighting Comanches, going up the cattle trail.” (It perhaps goes without saying that his description omits a staggering array of other “real people,” among them women and nonwhites.)

He admired these figures enormously and reconstructed their experiences by getting as close to them as he possibly could—whether by listening to their tales when he was a boy or chatting with them after he became a scholar—and then relying on observation and intuition (as well as archival research) to tell their stories. When Webb was challenged on how he used these methods in The Great Plains, he explained that he had conceived of the book not as a history but rather as “a work of art,” which is true enough, at least in terms of the fluid prose style that typifies most of his writing. But A Texan’s Story suggests that “myth” characterizes Webb’s oeuvre just as well.

Andrew R. Graybill is a professor of history and the director of the William P. Clements Center for Southwest Studies at Southern Methodist University.

This article originally appeared in the February 2021 issue of Texas Monthly with the headline “A Historian’s History.” Subscribe today.

- More About:

- Texas History

- Books