Do you know the lyrics to our state song? Okay, I’ll start with something a little easier: Do you even know the name of our state song? Some of you wiseacres might be thinking, “Why, of course I do, you dang Yankee. Get back to New York.” Truth is, I’m from Andrews, where pump jacks outnumber people and the air “smells like money.” I also know as well as any when to “get a rope.” And while I’m sure I learned the state song at some point growing up, I never gave it much thought—if any—until 2008. That’s the year I took a history class with Kent Finlay.

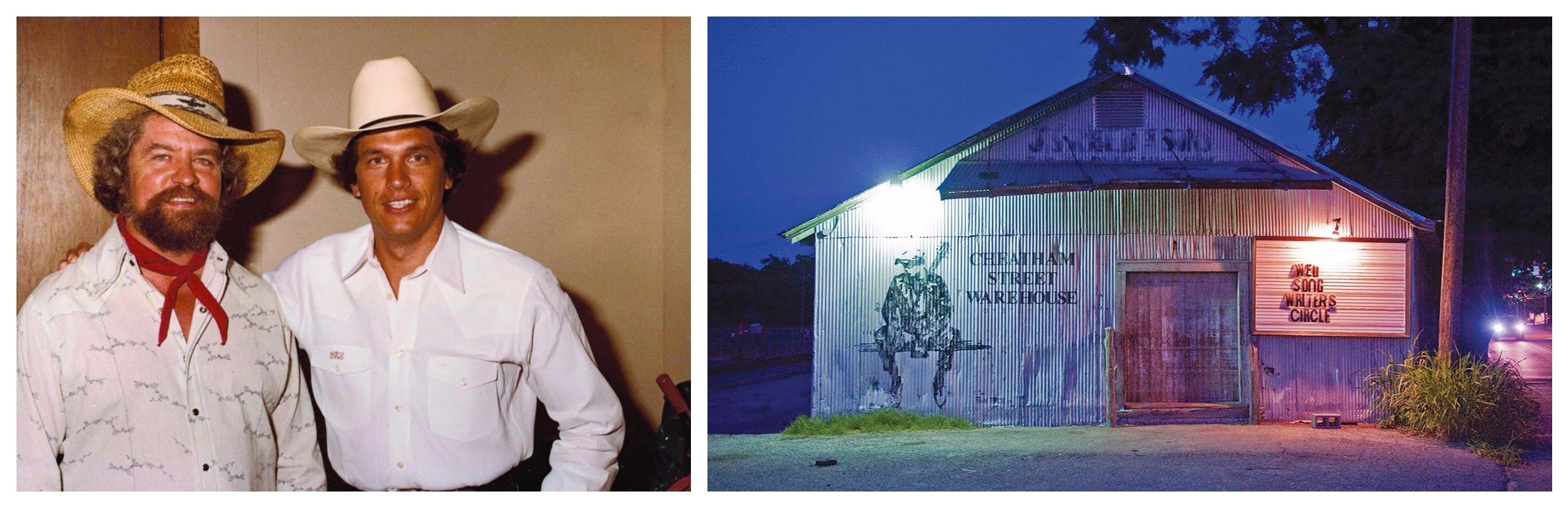

Now, I’ve enough horse sense not to try to sell anyone on my Texas bona fides; instead, I’ll tell you a bit about Kent’s. A native of Fife (“Just a rifle shot away from the geographical center of Texas”), Kent was a musician and historian. He got his first guitar during a Future Farmers of America trip to San Angelo in 1953, and from then on, hardly a day passed that he didn’t strum a set of six strings or scribble some verse. He moved to San Marcos in 1959, and he would often frequent the famous guitar pulls in nearby Luckenbach. In 1974 he opened his own venue, Cheatham Street Warehouse, a weathered, ramshackle honky-tonk that shook every time a train passed. Marcia Ball played on opening night, and soon after, Cheatham became a haven for songwriters. Kent nurtured the creative impulses of artists ranging from a young Stevie Vaughan (as he was billed then), Bruce Robison, James McMurtry, Randy Rogers, and Todd Snider to the most venerated of Cheatham Street’s alums, George Strait and the Ace in the Hole Band, who cut their teeth on Cheatham’s beer-stained stage every Tuesday (“Ladies free, nickel beer”).

While Kent took a humble pride in the remarkable success of the King of Country, the cornerstone of Kent’s legacy was the weekly Songwriters Circle he hosted on Wednesdays at Cheatham. Whether it was a road-hardened troubadour or a jittery nobody performing for the first time, Kent showered support on everyone who performed at his “songwriter’s church.” What set this circle apart from other barroom open mikes was that Kent didn’t give a damn about guitar chops or vocal virtuosity—he cared about the song.

Kent’s dedication to the craft earned him an important place in Texas music history. At some point, people started calling Kent the Godfather of Texas Songwriters. Despite his modest dismissal of the title, the epithet stuck.

I was a sophomore at Texas State University when I saw Kent’s “History of Country Music” in the course catalog. Intrigued, I enrolled. The curriculum was a casserole of historical lectures, well-spun stories, and old vinyl records played on a turntable for a small crowd of twenty or so students. My favorite part of class was when Kent (he was never Professor Finlay to us) would start talking about a piece of music and impulsively break into song, warbling a few lines like a singing encyclopedia before returning to the lecture as if nothing had happened.

During one class, his mood suddenly darkened when he queued up a particular song. His brow furrowed and disappointment filled his blue eyes as an unfamiliar marching tune boomed through the speakers. It was a sharp departure from what we’d been listening to: there was nothing of the gritty West Texas wind in it, no pain of the blues, no swagger of the cowboy. Instead, the song was self-important and vacuous, a brassy alma mater affair. The words were a sugary concoction of obtuse patriotic sentiment and rubber-wristed backslapping, a mouthful of cotton candy.

“Texas has all this great music, and this is our state song?” Kent said. He shook his head. “Texas deserves better.”

That was the first time I had ever really listened to “Texas, Our Texas.” Before Kent’s class, I didn’t care one way or the other about the tune. But Kent Finlay cared a whole hell of a lot. And I figured that meant that I should too.

Why Every Texan Oughta Also Care

No place hums with music like Texas. Pull out a map and you can sing your way across the state, from the “West Texas town of El Paso” to “Galveston, oh, Galveston.” This sweeping canon springs from a cultural identity steeped in music. Early Spanish colonization would eventually lead to the ascension of Tex-Mex sounds like conjunto, norteño, mariachi, and corridos. When the first Anglo Texians arrived in the 1800’s, they brought British ballads and fiddle tunes from colonial America. Black slaves contributed their own distinctive call-and-response songs and spirituals. The Germans and Czechs who immigrated to the Hill Country introduced waltzes, polkas, and, perhaps most important, the accordion, an instrument that would later be embraced by Tejano musicians. In Southeast Texas French-speaking African Americans developed a style known as zydeco, a mishmash of Cajun sounds and popular music.

As the twentieth century rocketed along, Texas became one of the most influential musical states in the country. Linden native Scott Joplin pioneered the ragtime piano that laid the framework for jazz. The first country recording was by Amarillo’s Eck Robertson, in 1922. The blues took hold here as strongly as it did in the Mississippi Delta, with giants like Blind Lemon Jefferson and Lead Belly cultivating the sound in Dallas’s Deep Ellum and the Sugar Land penitentiary, respectively. During the thirties in Fort Worth, Bob Wills and Milton Brown harmonized rural Texas–style fiddle and big-band, big-city jazz, a fusion we now call western swing. A decade later Ernest Tubb took the honky-tonk sound from Texas beer joints to a national audience. In the fifties Buddy Holly became one of the world’s first real rock stars and made Lubbock a mecca for future British invaders. In the sixties, Fort Worther Ornette Coleman blew his sax to experimental heights, while Roky Erickson and Janis Joplin got psychedelic in Austin. Willie and Waylon and the boys brought rednecks and hippies together and flipped a collective middle finger to Nashville in the seventies. Stevie Ray transcended the electric blues in the eighties. Selena broke cultural barriers in the nineties and was poised to become the first Tejano crossover superstar. And that barely skims the surface.

No easily portable tome—much less a magazine article—can hope to throw its arms around the enormity of Texas music history. The point I’m trying to make is that our musical heritage is important. Above oil, cotton, and big hair, it is our greatest export, a source of pride that should make every Texan’s head swell a size bigger than it already is.

A state song is meant to celebrate the richness and diversity of a place’s musical heritage. It’s a song used to welcome foreign diplomats. One sung by those missing home. A state’s personality expressed in whole, half, and quarter notes. Texas music is one instance where all our big talk is backed up, so there is no excuse for this state, with all of its auditory flavors, to settle for the musical equivalent of dry toast.

Which leaves one asking, how did we get stuck with “Texas, Our Texas” in the first place?

How Texas (Finally) Got A Song

When designating state symbols, some come easy (state footwear: cowboy boot); some elicit impassioned arguments (state dish: chili [instead of barbecue? Heresy!]); and some are downright silly (state hashtag: #texas). “Texas, Our Texas” became the fourth such token to receive an honorary nod (after the bluebonnet, the mockingbird, and the pecan tree), but a look back reveals that Texans have never fully embraced our state song.

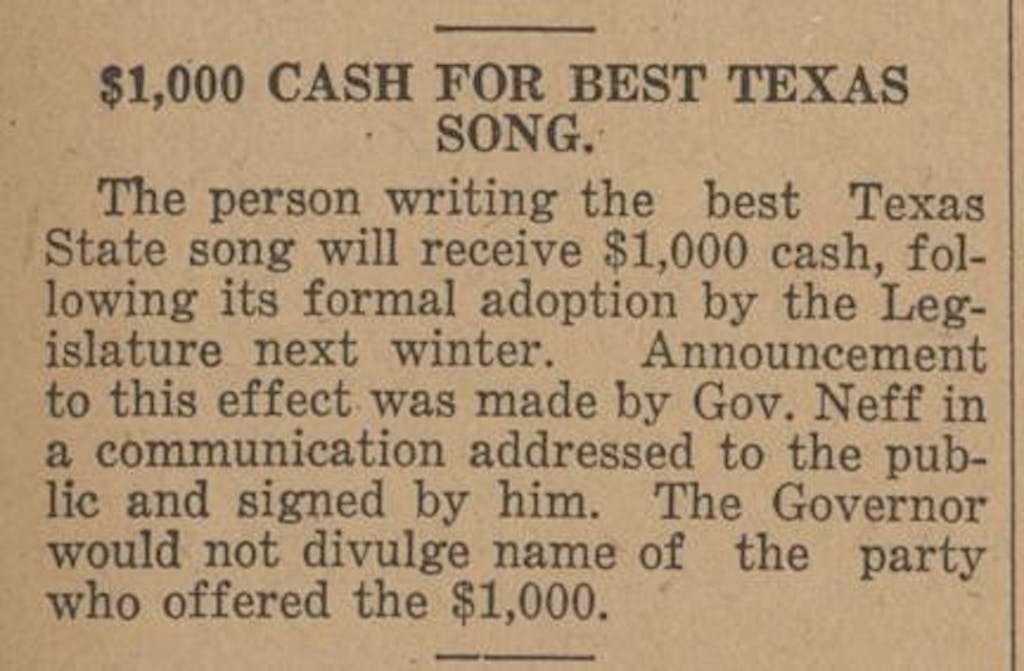

In 1923 Pat M. Neff, the state’s twenty-eighth governor, decided that we needed an official song. He issued a statewide challenge: write an original piece of music about Texas. If it was chosen as the state song, a group of private donors would pay $1,000 (approximately $14,000 today) to the winner. The call was heard by patriots (or capitalists) far and wide: 286 songs were submitted, many from outside the state, with one entry arriving from Italy and another from Brazil. Neff had handpicked a committee of sixteen “prominent Texans,” composed of both musically competent individuals and others who, as Neff put it, “were not supposed to know anything about any kind of music, but who knew a world of things about things generally, and knew how a State song ought to sound.”

One of those submissions was “Texas, Our Texas.” According to the Southwestern Historical Quarterly, the song was first conceived as a poem by Fort Worth native Gladys Yoakum Wright, in 1918. When the state song contest was announced, a friend urged her to share her patriotic verse with another Fort Worther, composer William J. Marsh. The two reworked Wright’s lyrics to fit an earlier piece of music written by Marsh, and finalized a draft in 1924. To be fair to the melody’s originator, Marsh was no musical slouch. (Nor a native Texan. Born in Liverpool in 1880, Marsh followed King Cotton to Fort Worth in 1904, becoming a naturalized citizen thirteen years later.) A musician trained at Ampleforth College in Yorkshire, Marsh served a long tenure as a professor of organ and theory at Texas Christian University. He published more than one hundred works throughout his career, including Texas’s first opera, The Flower Fair at Peking. Marsh was also a faithful Catholic and drafted the official mass for the state’s centennial celebration, as well as a whole bevy of hymns and sacred music. This may account for the churchlike solemnity of the state song’s sound and his attraction to Wright’s formal lyrics. (A sampling: “God bless you Texas! / And keep you brave and strong / That you may grow in power and worth / Throughout the ages long.”)

In December 1924 Neff’s group vetted the submissions over a two-day session in Austin, and “Texas, Our Texas” emerged victorious. (Well, not entirely. The second of three verses was rejected and had to be rewritten.) That, however, didn’t automatically catapult it to official state song status. Like anything trying to make its way through the bowels of the Texas legislative system, that process proved lengthy and arduous.

Five days before his term ended, in January 1925, Neff delivered an impassioned appeal to lawmakers to officially adopt “Texas, Our Texas.” His plea was not met with the same enthusiasm. The unconvinced members of the Thirty-ninth Legislature decided instead to form a joint committee of four representatives and three senators to stage two public hearings, where additional entries could be heard.

The decision dragged on into Governor Miriam “Ma” Ferguson’s term until, on March 18, 1925, the committee, “not being composed of experienced musicians,” reported that it could not agree on a clear winner and had selected the top six, including “Texas, Our Texas.” It was the committee’s recommendation that these six songs be sung by the public until the next legislative session “so that the people may be able to form an opinion as to which song should be adopted.”

Ferguson’s time in the pink dome was beset by controversy, so one might forgive her and her administration for failing to come to a resolution on this state song business. And so it fell to the desk of Governor Dan Moody in 1927, who cranked up the efforts once again, appointing a new committee using the same 1925 formula of reps and senators. Senator Margie Neal, of Carthage, the group’s chairperson, staged yet another contest, requesting that each of the 31 senatorial districts form a subcommittee to screen entries from their constituents and select a winner from each district. These nominees were then added to the 6 songs that had been chosen in 1925. The final 37 were further whittled down by the seven committee members, until, for the second time, “Texas, Our Texas” was blue-ribboned.

The Legislature officially adopted “Texas, Our Texas” by concurrent resolution on May 23, 1929, stating that it “had been selected by the Legislative Committee twice, proving the song was meritorious to the extent that it ‘had sung itself into the hearts of the people.’ ”

The newly designated state song was “ably and appropriately” dedicated in the hall of the House of Representatives on the evening of Tuesday, March 11, 1930. Neff was on hand for the occasion, as were composers Marsh and Wright, who handed over the song’s copyright to the state and collected the $1,000 check. Three renditions of the song were performed that day: one by the legislators, another by respected vocalist Pearl Calhoun Davis, and yet one more by the Wednesday Morning Music Club of Austin (apparently the Tuesday Evening Club was unavailable).

The song’s only revision was prompted by Alaska’s annexation, in 1959. Marsh replaced the word “largest” with “boldest.” That same year, Governor Price Daniel designated March 6, the 123rd anniversary of the Alamo’s fall, State Song Day. To celebrate the occasion, Daniel arranged for a recording of the song to be broadcast on the radio and television, encouraged bands across the state to perform it, and required the in-session Senate to sing it.

Yet despite the protracted process and prolonged hype and promotion, the state anthem never quite managed to strike the right chord with Texans.

The Official Unofficial State Songs

Over the past few months, I conducted an experiment. Whenever I found myself in a gathering of native Texans, I asked if they could name the state song. Just about everyone had an answer, but few had the right one. And not a single person could lilt more than a lick of “Texas, Our Texas.”

At least one journalist predicted this scenario back in 1930. The Waxahachie Daily Light ran the following editorial: “The Legislature has paid out $1,000 of the dear peepul’s [sic] money to the composers of the state song. We’ll wager a pewterfied [sic] buffalo nickel against a rancid doughnut that ninety-nine out of every hundred native sons and daughters never memorize it beyond the first verse and chorus.” Sounds as though they had an oracle working in Waxahachie.

One by-product of my investigation was the discovery that Texas has at least three official unofficial state songs. The most common response to my poll was “The Yellow Rose of Texas.” Not a bad answer; as one friend said, “The Yellow Rose” is embedded in the genetic makeup of Texans the way Journey’s “Don’t Stop Believin’ ” is in Detroiters. But the song has a checkered history. The lyrics originally contained racial slurs, and the tune was popular with both blackface minstrels and Confederate troops. The song’s reputation is further complicated by its association with the Texas legend of the Yellow Rose, a mixed-race woman named Emily West, who supposedly kept Santa Anna “occupied” while Sam Houston’s army launched its surprise attack at San Jacinto. With Virginia and Florida both retiring state songs with questionable racial references, it’s best that Texas leaves the “Yellow Rose” to Hollywood mythmakers.

Other oft-guessed ditties were “The Eyes of Texas” and “Deep in the Heart of Texas.” Both are songs that Texans grow up singing, like Christmas carols or “The Star-Spangled Banner.” They’re classics you’ve known for so long that you can’t recall the first time you heard them—their melodies buried somewhere deep inside—and occasionally you’ll catch yourself singing a refrain without meaning to, like when a line of “Jingle Bells” slips out in July. The glaring problem with “The Eyes of Texas” is that Aggies and a certain border collie might keel over if we elevated the Longhorns’ anthem to official state song status.

This leaves “Deep in the Heart of Texas.” It probably has the strongest case for official designation. Grade school music teachers drilled it into each of our heads to clap-clap-clap-clap after “big and bright,” and opportunities to show off this rhythmic feat are readily available at various events across Texas, from ball games to concerts. Drawbacks include the fact that the song wasn’t written by a Texan, nor was it originally sung by one. Perry Como recorded the first hit version two days after Pearl Harbor, and the jaunty ballad ended up becoming so popular that the BBC stopped playing it during work hours. Apparently, the chance of ammunition workers’ dropping their tools to clap was too risky. Today the song may feel a tad hokey, but when George Strait played it during his farewell tour, last summer, the stars did seem bigger and a little brighter.

Two (or Three or Four) Tunes Are Better Than One

Kent Finlay was the first person to show me this chink in our cultural armor, but he’s not the first to gripe about the state song. Since its official adoption, “Texas, Our Texas” has been a point of contention for scholars, music lovers, and concerned citizens. Texana expert Anne Dingus called for change in the pages of this very magazine, while Texas historian and Texas Monthly contributor Lonn Taylor has made the same plea on his history program on Marfa Public Radio. The fact that Taylor has expressed his wish for a new state song is particularly significant. His cousin was Gladys Yoakum Wright, a.k.a. “Gladys, Our Gladys” to his family.

Even lawmakers have gotten in on the act of bashing the state song. In 1963 Representative Bill Walker, of Cleveland, recommended an alternative to the House, saying that “Texas, Our Texas” was “difficult to sing, especially by large gatherings”; was not widely known; and that it “lack[ed] the martial character needed and desirable in the state song of the great state of Texas.”

So why has the call to change it gone unanswered? Perhaps Kent and the other dissenters have been barking up the wrong metaphorical tree. Instead of sending poor Wright and Marsh out to pasture, perhaps we should be sending them more melodic company. Adopting multiple state songs is the status quo throughout the U.S. In fact, each of our neighboring states has no fewer than five. In addition to two state songs, Arkansas has a waltz, a historical song, and a state anthem. New Mexico has designated Spanish and bilingual songs as well as a state song, state ballad, and a cowboy song. Louisiana has made room for two state marches, two state songs, an environmental song, and an ode to “Hurricane Katrina and Hurricane Rita recovery efforts.” Oklahoma has eight, with gospel, country and western, children’s, rock, and folk among the types of music represented.

When it comes to volume, Tennessee outshines the rest of the U.S. by far. In addition to its six official state songs, there’s been legislative recognition for seven others, including a bicentennial rap. Other states have given official status to genres such as glee club and polka (Massachusetts), lullaby (Montana), bluegrass (Kentucky), and cantata (Connecticut).

As it happens, it’s not so difficult to designate an additional state song. Texas has done it once before. In 1933 Julia Booth and Lora Crockett, of Chappell Hill, were upset that the newly sanctioned state song failed to mention the state flower. The two composed their own tune, trekked to the Capitol, and had a soloist perform their freshly inked “Bluebonnets” for the lawmakers. No committees were formed or additional contests held. The Legislature politely passed a joint resolution proclaiming it the state flower song with no further reasoning than “This State has no State Flower Song.”

Following that logic, nor does this state have a Tejano song or a western swing song, despite Texas’s being the birthplace of those genres. If we’re stuck with “Texas, Our Texas,” we might as well follow our neighbors’ lead and elect it some company. The question is, with so much first-rate Texas music, where do we start?

Opening Pandora’s Jukebox

Trying to proffer a list that the whole state can agree on is about as foolhardy as walking a tightrope over a pool of alligators with Christmas hams tied to your ankles. Any list that attempts to encompass Texas music is going to miss something. One quickly realizes why it took six years for lawmakers to settle on “Texas, Our Texas.”

Now, I can guarantee you that I’m well aware of the size of my britches, and I ain’t too big for them. Rather than put forth a definitive list, I can only suggest my personal preferences. And isn’t that kind of the point? To link our cultural identity to music that personally affects us, that moves us in some way, tethers us together as Texans?

I’ll start with an easy one: the state waltz. My nominee is Ernest Tubb’s “Waltz Across Texas.” This is a song that kindles memories for many Texans, striking a perfect balance of nostalgia and timelessness. It’s the song I danced to with my granny on a warm June night, her sixty-seventh birthday, the vinyl spinning on an old record player on her back porch and ol’ E.T.’s voice moving our boots across the floor. This is a song deserving of legislative recognition.

Waltzing is great and all, but Texans are more inclined to two-step. What better to scoot a boot to than our official state music, western swing? This genre is unequivocally Texan, and its king is Bob Wills. His signature single, and one of the defining tunes of western swing, is “New San Antonio Rose.” This jazzy number, recorded in 1940, grooves back and forth between straight-ahead swing and campfire cowboy music, exemplifying the best of his Texas Playboys’ innovative musicianship. The one hitch is that the song centers on a specific location. But that shouldn’t derail its accreditation, especially considering the place in question happens to be the Cradle of Texas Civilization (go on, fight me). What could be more patriotic than “Deep within my heart lies a melody / A song of old San Antone”? It’s the modern equivalent of Remember the Alamo, except with a melody that rallies dancers to the floor.

While Wills is the King of Western Swing, Selena Quintanilla Pérez holds a crown of her own: the indisputable Queen of Tejano. The first Tejano musician to win a Grammy, in 1994, Selena brought national notice to this uniquely Texan genre. Her short but stellar career included numerous hits, which makes pinpointing the one track that deserves the statewide nod a difficult task. Of her top tracks, “Como La Flor,” a ballad of unrequited love, is hard to best. The plaintive lyrics may have the toughest hombres struggling to keep their lacrimal glands in check, but the emphatic bass line and irresistible beat have been driving dance circles at quinceañeras and proms for over two decades. While the song isn’t specifically about Texas, neither is Ohio’s official rock song, “Hang On Sloopy,” about the Buckeye State. Not all state songs need be self-aggrandizing, jingoist jingles.

Another school of music deserving a tip of the hat is hip-hop. Artists like Bun B, the Geto Boys, DJ Screw, and Erykah Badu have made lasting impressions on the sound while maintaining their ties to Texas. Even if many of these tracks feature language that runs contrary to the effete sensibilities of Capitol suits, these songs give voice to often marginalized members of our community. I’m partial to UGK’s “One Day,” a wrenching ode that offers insight into the lives of its Port Arthur writers, Bun B and Pimp C.

One category that shouldn’t wrinkle the legislative khakis too much is country. There is no shortage of twang-tinged odes to Texas or of opinions on which of these are top dog. Before y’all go hurling your rotten vegetables, let me say that not every country tune with “Texas” in the title is worth a “pewterfied buffalo nickel.” By the same token, not every good song about Texas has the word in the title. One such track is “London Homesick Blues,” penned by Gary P. Nunn and performed on Jerry Jeff Walker’s ¡Viva Terlingua! It is one of the seminal songs for Texpats missing home, with a refrain that demands to be hollered no matter the setting. “I wanna go home with the armadillo / Good country music from Amarillo and Abilene / The friendliest people and the prettiest women you’ve ever seen.”

Even after all this chin-stroking, I have yet to mention our patron pigtailed saint. Willie Nelson’s recorded a wealth of Texas ballads (including the 1968 album Texas in My Soul, made up entirely of state-loving songs), but I suppose the official Willie state song could be whatever he happens to be humming at the time.

There’s still so much good music to consider. What about a state polka or a blues anthem? Or pieces from songwriting titans like Cindy Walker, Kris Kristofferson, and Townes Van Zandt? What about ZZ Top’s Texas rock songs? Heck, what about Beyoncé?

Maybe it’s time to assemble the Fellowship of the Song, a meeting of the most talented Texas songsters, from indie rock’s Annie Clark to Tejano legend Flaco Jiménez. If our best living maestros convened over a few cans of Lone Star, perhaps they could orchestrate a tune that might actually sing its way into the hearts of Texans.

Certainly a state with as much geography and ego as Texas can handle a full stable of state songs, and unlike the governors of yesteryear, we no longer have to entrust the privilege of choosing one to a handful of tone-deaf lawmakers. Today we have the luxury of digital democracy, which allows anyone who can work a smartphone—or hobble to a county library, if necessary—the chance to voice their opinion online. Surely we could put this newfangled technology to good use by crowdsourcing the selection process. In fact, someone’s already kicked off the movement; there’s an online petition pushing for the adoption of Ray Wylie Hubbard’s “Screw You, We’re From Texas.”

If I were to start my own petition right now, of all the songs I’ve considered, I’d have to put forth my friend Kent Finlay’s “What Makes Texas Swing.” For one, it checks all the right boxes: barbecue, beer, honky-tonks, friendly people, weather, silver buckles, and a slew of Texas idioms and small towns. The song do-si-dos enthusiastically without an iota of irony or cheese.

It would also be a memorial to my friend, who died last year on Texas Independence Day from complications of cancer. I lost the mentor who taught me to really hear Texas music, and Texas lost one of her finest songwriters. When we last spoke, the week before he died, Kent didn’t mention his disappointment in the state song, but he did croon a few lines that he was working on and a few more from songs he’d finished long ago. Kent understood the importance and power of music—its ability to bring people together on a dance floor or across decades. He treasured it as one of life’s greatest pleasures, and he taught me to do the same.

- More About:

- Texas History

- Music

- Longreads

- Selena

- George Strait

- Bob Wills

![Willie_1280x230[10][1]](https://img.texasmonthly.com/2016/02/Willie_1280x230101.jpg?auto=compress&crop=faces&fit=fit&fm=pjpg&ixlib=php-3.3.1&q=45)