This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

Onomasticians—those who pursue the study of names—would be among the first to tell you that Texas is the only state to inspire a decent nickname.

Such specialists, who for some reason tend to be British, have a tough time coming up with names for the other states. The nickname “Buffalo,” for example, they give to North Carolina. Or “Fly-up-the-creek”—that’s Florida, in case you didn’t know. Then there’s Nebraska’s “Bug-eater.”

Of course you could argue that John Bull doesn’t know doodly squat about American nicknames, but it doesn’t take much expertise to recognize that “Monty Montana” just doesn’t cut it. A Nebraskan who doesn’t want to be called Bug-eater could always go by the name “Neb,” but that sounds like someone you would say “Come on out from under the porch, Neb, and eat your supper” to. Then there’s always “Cal.” “Are you through in the bathroom yet, Cal?” Face it: besides “Tex,” no state moniker gives an indication about the man, except that maybe he’s a wimp.

Nicknames have been around as long as there have been people to wear them. Every name is nicked from some root, often as a method of quaint identification with a place, occupation, description, joke. Somehow “Tex” embraces all those categories. It sums a person up, or ought to.

Not many moms and dads name their children Tex at birth. It’s a name, after all, that’s supposed to attach itself to you. Hard-core Texans, we would like to believe, don’t feel the need to advertise, and the rest of us would just as soon have our children enter the twenty-first century unfettered by an antique regional nickname. The result is that most Texes don’t come from Texas. Texas E. Schramm, who is a venerable source on how one gets Texed, was born in Los Angeles and says, “It really doesn’t make a difference where you’re from.”

Take Tex Johanssen. He’s from Wisconsin. Never been to Texas; probably never will. All he did was like horses. When he finally bought a horse, his wife nicknamed him Tex. They then moved to New Mexico. Make sense?

Tex Mulka hails from Michigan. He’s short, stocky, and more Pole than Bevo is beef. He’s a stevedore to boot. How did he get graced with “Tex”? When he was in the Army, in Japan of all places, someone flung it at him and—perhaps because it so plainly did not fit—it stuck.

So they can come from Los Angeles as easily as from Lubbock, from Dubuque as easily as from Dallas. It doesn’t seem to matter. If you pour André champagne into Taittinger, 200 million people wouldn’t know the difference. Likewise, any fool can wear a name just as easily as he can wear a cowboy hat. Still, “Tex” ought to be more than an ornament you put on like a $21.85 John Wayne commemorative belt buckle.

When politburo member Vladimir Shcherbitsky was in Texas to sell peace and shop at Neiman’s, he was presented with a cowboy hat and boots. Did that make him Tex Shcherbitsky? Could you as easily plop a fur cap on Jim Wright’s head and call him Ruski Wright? That kind of flimflammery underscores the problem. People still carry the name “Tex,” but does it still carry them? In other words, has “Tex” lost its meaning?

Perhaps the Texas has been bred out of “Tex,” and the name is now no more Texan than “Joe” or “Frank” or even “Abdul.” Some folks would even argue that Tex and Texas have gone the way of Achilles and Troy; we’re just another mound of mythified rubble upon which onomasticians exegete.

Don’t bet on it. Texas is changing, and Tex is changing with it, but who among us would advise Tex Ritter, if he were starting out today, to use his given name, “Maurice”? The truth is, it’s not the world that’s expanding into Texas, it’s the other way around. After all, God didn’t spend five out of six days on Texas for nothing. And Tex plants an image through the fields of fact and folklore—it matters not whether the image is real, only that the man is.

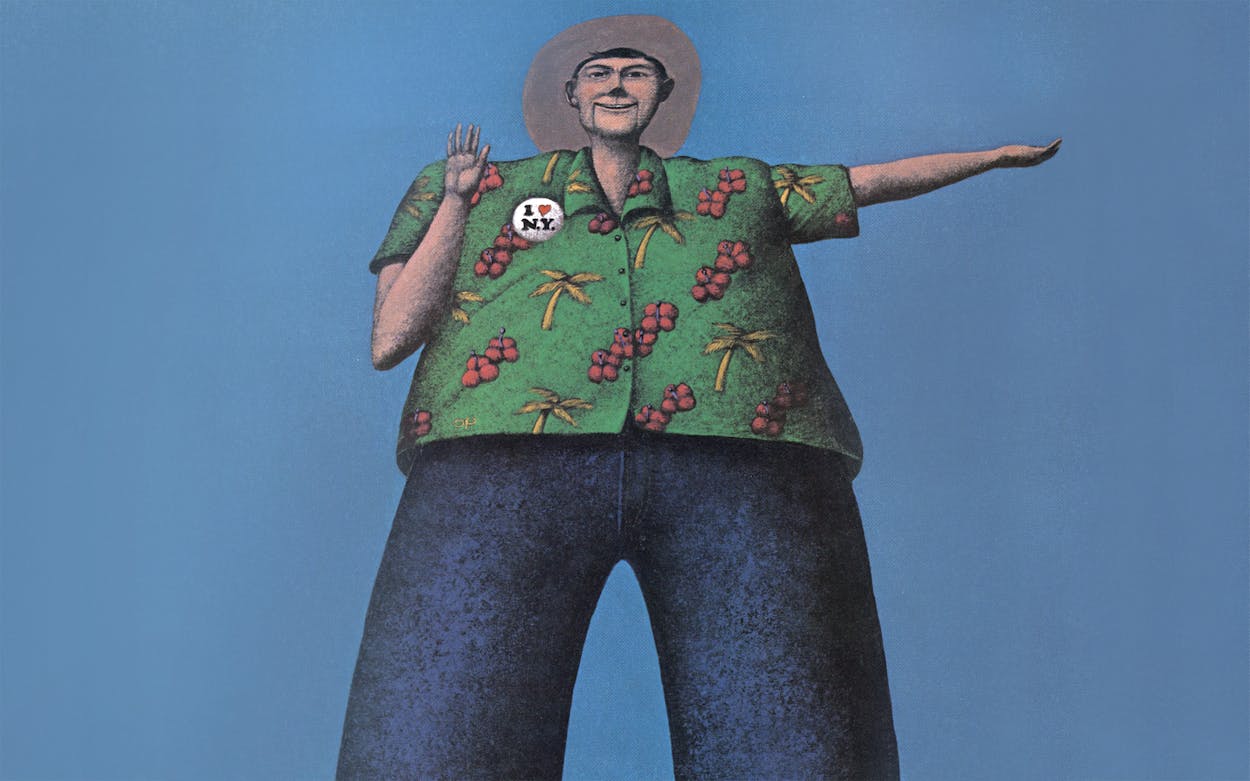

The nickname “Tex” stands on its own, just like the most famous Tex of all. Fifty-two feet tall, wearing jeans, boots, and a hat as big as the roof of a house, Big Tex stands smack in the middle of Big D fairgrounds, his arms and grin spread wide. For all we know, his real name might be Maurice too, but nobody would ever call him that to his face.

Gary Cleve Wilson, a writer who lives in Austin, was called Tex when he was in the army.

- More About:

- TM Classics