What it was was a generational shift, and not one that Music Row wanted. In the late sixties, Nashville country music was defined by the string-swelling, countrypolitan gloss of Tammy Wynette and Glen Campbell. RCA executive Chet Atkins was a chief architect of the Nashville sound, and when people asked him to define it, he liked to jingle the change in his pockets and say, “It’s the sound of money.” No tweaks to the formula were tolerated. Even Willie Nelson and Waylon Jennings, two Texas boys with ideas of their own, were forced to fit the mold. They recorded for RCA, and their records sounded exactly the way Atkins wanted.

The rest of the nation had less success maintaining the old order. In cities like San Francisco, the counterculture was popular culture. Hair was long, love was free, and dope smoking was considered tame. The music ranged from the psychedelic extremes of Jefferson Airplane to the rootsier jangle of Creedence Clearwater Revival, with acts like Janis Joplin and the Grateful Dead straddling the two. Nashville, with its pompadours, whiskey, and quiet reliance on truck-driver amphetamines, had no use for any of it. When Los Angeles bands like the Flying Burrito Brothers started playing country rock, winking at Nashville in Nudie suits festooned with rhinestone pot leaves, Music Row responded with disgust.

Halfway between the coasts sat Texas, where hundreds of honky-tonks functioned as Nashville’s farm system. But that music belonged to the old guard. Texas kids were more interested in the state’s thriving folkie circuit. The hub was a Dallas listening room called the Rubaiyat, from which young singer-songwriters like Steve Fromholz and B. W. Stevenson sallied forth to coffeehouses around the state. The music they played was distinct from the protest songs of Greenwich Village. Texas folk was rooted in cowboy, Tejano, and Cajun songs, in Czech dance halls and East Texas blues joints. It was dance music. And when the Texas folkies started gigging with their rock-minded peers, they found a truer sound than the L.A. country rockers. There was nothing ironic about the fiddle on Fromholz’s epic “Texas Trilogy.”

It’s impossible to pinpoint the exact moment when that sound and scene coalesced into something cohesive enough to merit a name, but then again none of the labels people came up with—cosmic cowboy, progressive country, redneck rock, and, ultimately, outlaw country—made everyone happy. Still, the pivotal year was 1972, and the place was Austin. Liquor by the drink had finally become legal in Texas, which prompted the folkies to migrate from coffeehouses to bars, turning their music into something you drank to. Songwriters moved to town, like Michael Murphey, a good-looking Dallas kid who’d written for performers such as the Monkees and Kenny Rogers in L.A. He was soon joined by Jerry Jeff Walker, a folkie from New York who’d had a radio hit when the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band covered his song “Mr. Bojangles.” In March, Willie played a three-day country festival outside town, the Dripping Springs Reunion, that would grow into his Fourth of July Picnics. Then he too moved to Austin and started building an audience that didn’t look like or care about any Nashville ideal. By the time the scene started to wind down, in 1976, Willie and Austin were known worldwide.

To say that Nashville eventually got hip to what was happening would be too kind. Rather, the industry identified a chance to make money and came up with the “outlaw” label, which now applies to one more subset of the Nashville establishment. While it rightly conjures images of Willie, Waylon, and the boys, other stars who made careers off it, like Hank Williams Jr., couldn’t have had less in common with hippie poets like Murphey and Fromholz. But something more than marketing persists in the label. It was coined to describe country songwriters who wouldn’t conform to traditional strictures, who insisted on making music that sounded right to them. What follows are their stories of how they pulled that off.

Country Stars and Folkies

As the seventies began, there were two major schisms bearing down on Austin’s budding country music scene. The first was political. The cultural upheaval of the sixties was still going full force, particularly in Texas, even in a city that considered itself as forward thinking as Austin did. The second related more narrowly to the music. The only route to success for young Texas country songwriters went through Nashville, a stubbornly conservative industry town considered every bit as reactionary as the Nixon administration. Even Kris Kristofferson, a Brownsville-born Rhodes Scholar who followed the traditional path—he worked as a janitor at a Nashville recording studio before he started collecting number ones in 1970—failed to fit in. His writing was considered too esoteric. More to the point, his hair was too long.

BILL BENTLEY wrote for the Austin Sun, a biweekly newspaper. I was in school in Georgetown in ’68 and would come down to the Vulcan Gas Company [Austin’s preeminent counterculture nightclub] to see shows, then walk over to I-35 at two in the morning and hitchhike home. One time I got picked up by these rednecks, and, man, they drove me out into the country and said they were gonna kill me. It scared the shit out of me. I started leaving the club early enough to catch the last Greyhound back.

ALVIN CROW led a western swing band in Amarillo. We had long hair in my band, and a couple of the guys got pulled over in a little town called Ralls. The cops kept them for three days, then shaved their heads. It was even that way around Austin. If you were driving in from Lubbock or Amarillo with long hair, you had to get down on the floorboard in places like Oak Hill because you’d get pulled over.

RAY BENSON moved his western swing band Asleep at the Wheel from Berkeley to Austin in 1973. Music separated people. Country music fans were for the Vietnam War, like Merle Haggard and “Okie From Muskogee.” The hippies—and the Grateful Dead and Rolling Stones—were against it. And never the twain shall meet. If you walked in the Broken Spoke with long hair in 1969, you’d get your ass kicked and your hair cut.

MICHAEL MARTIN MURPHEY was a songwriter, known then as Michael Murphey. I went to do Ralph Emery’s Nashville radio show, and taped on the studio door was a Flying Burrito Brothers album with “This is NOT country music” written on it in red and X’s through the faces of the Brothers.

ROGER SOVINE was an executive at BMI Nashville. The guys who made the records in Nashville were people like Owen Bradley. He had an orchestra that played high school proms on the weekend, but during the week they played on Webb Pierce and Brenda Lee records. They had a round sound, no edge. In Texas you’d hear people like Billy Joe Shaver. They had an edge.

DAVE HICKEY was a cultural critic who occasionally wrote songs in Nashville. You have to understand the way Nashville worked. The “talent” were basically slaves of the record company. They’d come off the road once every three months, go into the studio, get handed lyric sheets, sing to prerecorded songs, and then go back on the road.

WILLIE NELSON was a Nashville songwriter. I recently found a bunch of my demos from 1961 to ’64, and I like the sound I was getting. But then the record companies overproduced it. They’d have had a real good record if they’d just released the demos.

RICHIE ALBRIGHT played drums for Waylon Jennings. Chet Atkins signed Waylon to RCA in 1965 and produced his first few albums. But then Chet cut back on producing and passed Waylon around to guys we didn’t feel we had a whole lot in common with.

DAVE HICKEY You couldn’t even cut a song Chet didn’t like, and it produced a war of cultures. In Nashville everybody acquiesced to the class structure. They’d think, “We may be poor, but we don’t want to be destitute, so we won’t make waves.” The temperament of Texas is more optimistic. People in Texas may be poor, but they keep thinking they’re going to win the football pool. There was a cultural optimism running through Waylon, Willie, and Billy Joe.

BILLY JOE SHAVER was a songwriter from Corsicana. I had a borrowed motorcycle that I ran up on [legendary Nashville songwriter] Harlan Howard’s porch. I was a little bit inebriated. So I kinda knocked on his door with my front wheel, and he comes to the door, and I said, “God dang, are you Harlan Howard?” He said, “Yes.” I said, “Well, I am Billy Joe Shaver, and I’m the greatest songwriter that ever lived.”

STEVE EARLE was a songwriter living in Houston. We were all essentially folkies who followed Kristofferson to Nashville, rather than Willie or Roger Miller. No offense, but they were traditional writers who happened to be incredibly good. Transcendent. But Kristofferson was post-Dylan.

TOM T. HALL had his first top ten country hit with “Ballad of Forty Dollars” in 1968. Kris came to town and created an illusion of literacy. Somebody said once that he and I were the only guys in Nashville who could describe Dolly Parton without using our hands.

BILLY JOE SHAVER Chet Atkins didn’t like me for shit—I guess because I was a kind of derelict-looking guy in a cowboy hat. I played some songs for [longtime Nashville star] Charlie Louvin one night, and he said, “Have you been driving a truck or something?” I said, “Yeah, I do just about everything. I’ve been cowboying, driving a truck.” He said, “I’d go back to that. These are about the worst songs I’ve ever heard.” My writing was different. I wrote like I talked, a little off the wall every once in a while. He didn’t get it.

DAVE HICKEY I can’t tell you how much these guys scared Nashville. Texans didn’t know who was boss. They were regarded as wild Indians.

At the end of 1971, while Willie and Waylon were still trying to negotiate the Nashville grind, three transplants to Austin pushed the small folk scene toward a new kind of country. San Antonio native Doug Sahm ended his five-year exile in San Francisco and returned to Texas a full-blown hippie rock star, with two Rolling Stone covers under his belt. Spooked by a California earthquake, Michael Murphey moved to Austin, but not before recording a first album for A&M Records, Geronimo’s Cadillac. And Louisiana piano player Marcia Ball, stuck in Austin when her car broke down on a road trip, decided to stay.

BILL MALONE was a graduate student in history at the University of Texas whose dissertation grew into Country Music, U.S.A., published in 1968. The Austin folkies were storytellers, and when that folk revival began to decline, country music was the place for them to go. Guys like Steve Fromholz played guitars, had the twang in their vocals, and filled their songs with the life they knew, which was country life and country people.

BOBBY EARL SMITH was a UT law school graduate from San Angelo playing bass in country bands. In early ’72 my band, Dub and the Dusters, was playing at the One Knite. Our drummer was Freddy Fletcher, Willie’s nephew, who was still in high school. When we take a break, he disappears. Fifteen minutes go by, then twenty, and the club owner is on my ass. Well, it’s just a block from the police station, and everybody’s out back smoking dope, so one possibility is he’s been hauled off to jail. Finally he shows up and says, “I just met this long-legged hippie chick with some incredible dope, and she’s a singer. Can we get her onstage?” So we called her up. It’s Marcia Ball. And she sang “Me and Bobby McGee.” That’s the birth of Freda and the Firedogs.

MARCIA BALL had just moved from Baton Rouge. I had to tell Bobby Earl that “Bobby McGee” was my entire country repertoire. So he came to my house and taught me all these classic country songs. It gave me goose bumps. It was a real revelation.

JOE NICK PATOSKI wrote for Rolling Stone and the Austin Sun. The first time I ever heard country music and saw cool people at the same time was at one of Freda’s Sunday night shows at the Split Rail. That was a transformative experience.

BILL BENTLEY Doug [Sahm] knew a good, free backup band when he saw one, so he started sitting in with Freda, bringing his hippie groove. He’d been playing with the Grateful Dead. His leads were sparklier, wilder, they went on a little longer. He didn’t have a beautiful voice. It was raspy, hard-edged, and it put a different spin on country. He showed Marcia that you could jack Patsy Cline up a couple notches.

MICHAEL MARTIN MURPHEY Bob Dylan’s producer, Bob Johnston, heard me and [bassist] Bob Livingston play at the Rubaiyat and asked us to come to Nashville and make a record. We said, “When?” and he said, “How about now?” So I borrowed my dad’s Buick, drove all night, and immediately went in and made Geronimo’s Cadillac. Gary P. Nunn [Murphey’s piano player] came up with some of the other guys who later became my Cosmic Cowboy Orchestra.

STEVE EARLE Geronimo’s Cadillac is a record I know every second of. It was based on country music, it had a steel guitar, but it really was progressive.

MICHAEL MARTIN MURPHEY Geronimo’s autobiography had a picture of him sitting in a car in a top hat and tuxedo, which was like surrealistic art for me. It was a trumped-up publicity stunt that the government circulated to say, “Geronimo is becoming white! Everything is fine!” But there’s an intensity in his eyes that says, “I may be in a denigrating position, but I survived.” So I wrote that song.

JOE NICK PATOSKI The frat and sorority kids started digging Murphey. That bigger audience was critical.

CRAIG HILLIS was Murphey’s guitarist. The band all moved into an old motor court on North Lamar. The drummer had a cabin, I had one, and Murphey and Gary P. lived in the big house.

GARY P. NUNN I called it “Public Domain Incorporated, My Home for Runaway Fathers,” because every wayward musician who came through town would end up staying there. Jimmy Buffett used to come by. The Doobie Brothers showed up in Cadillacs one night.

CRAIG HILLIS One night Jerry Jeff showed up looking for Murphey. Jerry Jeff was on his way from Key West to Los Angeles, all jazzed about his new deal with MCA giving him artistic license to make records the way he wants. He sticks his head in, and pretty soon we’re passing around guitars. The cross-pollination starts there.

Cosmic Cowboys

That impromptu picking session proved fortuitous. A monstrously hard-living folk troubadour out of the Greenwich Village scene, Jerry Jeff had gotten fed up with his previous label, Atlantic, for the same reasons Willie was frustrated in Nashville. Atlantic had paired him with Memphis soul musicians, players whose sound he found too bold and clean. When Jerry Jeff learned that his new label, MCA, had deposited a sizable, three-record studio budget in a New York bank account, he decided to spend it making records that sounded right to him.

He got the opportunity to do just that when he decided to stay in Austin. In the spring of 1972, backed by Murphey’s band, he recorded Jerry Jeff Walker. It was a slapdash production, completely unlike the polished work the players had done with Murphey, and it established a new, organic Texas sound. It also introduced the world to the songs of Monahans native Guy Clark, whose “L.A. Freeway” and “That Old Time Feeling” were album highlights.

RAY WYLIE HUBBARD was a Dallas folkie. The first time I saw Jerry Jeff was at the Rubaiyat. There was this little statue of Pan, the guy playing the flute, over in the corner. When Jerry Jeff comes up onstage, with a guitar and a harmonica rack, he takes off his hat and sails it across the crowd, and it lands on this statue. He was mesmerizing.

GARY P. NUNN Jerry Jeff showed up for a gig one night in a bathing suit, a vest, a cowboy hat, and maybe a bandanna. He’d been drinking Brandy Alexanders all day. We get him onstage, but he couldn’t remember any lyrics. After about three songs, some girl hollered, “Get off the stage, you drunk son of a bitch.” He responds, “F— you, f— you,” and then finally, “You ain’t got no beer. You ain’t got no cocaine. You ain’t got no pussy. You ain’t got anything I want.” Then he fell into the drum kit. The whole band walked out the front door, but he ended up playing by himself until one o’clock. That was the deal: he’d do the craziest things, but it’d always be funny when the story was told.

JERRY JEFF WALKER I had a whole lot of money available, and I knew what people like the Band were doing. You buy the equipment, make your record, and when you’re done, you own the shit! I thought that might be a good thing to do.

BOB LIVINGSTON Someone had gutted the old Rapp Cleaners on Sixth Street, put burlap on the walls, and made it one of Austin’s first recording studios. We’d been with Murphey in a Nashville studio, and now we’re with Jerry Jeff in this funky little place, plugged into a sixteen-track tape recorder in the middle of the room, with no board, no nothing. We’d get there about seven each night, and Jerry Jeff would be standing in the doorway, mixing sangria in this big metal tub.

JERRY JEFF WALKER The sound engineers wanted to bring in this souped-up equipment. I said no. This needed to be like one of those nature shows: [He whispers in an affected English accent]“This is the first time we’ve ever seen the birthing of a Tibetan tiger baby.” I figured if somebody could sneak up on a tiger, we could be recorded where we’re comfortable.

CRAIG HILLIS Jerry was the ringmaster. People like [East Austin piano player] the Grey Ghost would just drop in off the street and sit in, and then management would have to figure out later who had played.

JERRY JEFF WALKER Murphey constantly told the band what to do. I came from the other school of “You guys are musicians. So if I play a folkie tune like ‘Little Bird,’ play something folkie on it. If I’m playing ‘L.A. Freeway,’ something that’s more rock and roll, play something rocky on it.”

HERB STEINER played steel guitar with Murphey and Jerry Jeff. There was always tension between Jerry Jeff and Murphey over the band. One night we were on a break from recording with Jerry Jeff, and I went into the sandwich shop next door. Murphey was sitting there with his guitar and said, “Listen to this.” He’d written “Alleys of Austin.” Just a beautiful song.

EDDIE WILSON owned the Austin concert venue the Armadillo World Headquarters. Murphey needed to be more like Jerry Jeff, and Jerry Jeff needed to be more like Murphey. That’s probably what it came down to.

While Jerry Jeff was working on his record, Willie was contemplating dramatic changes of his own. Though he was one of the most successful songwriters in Nashville, eight years of jumping through RCA’s hoops in an effort to become a recording star had worn him out. After his Tennessee home burned down two days before Christmas in 1970, he spent the next year in Bandera, occasionally returning to Nashville to record. By early 1972, the house was rebuilt, but Willie was done with Music Row. He wanted to start over, and as he considered locations from which to do so, he booked a gig that would point the way.

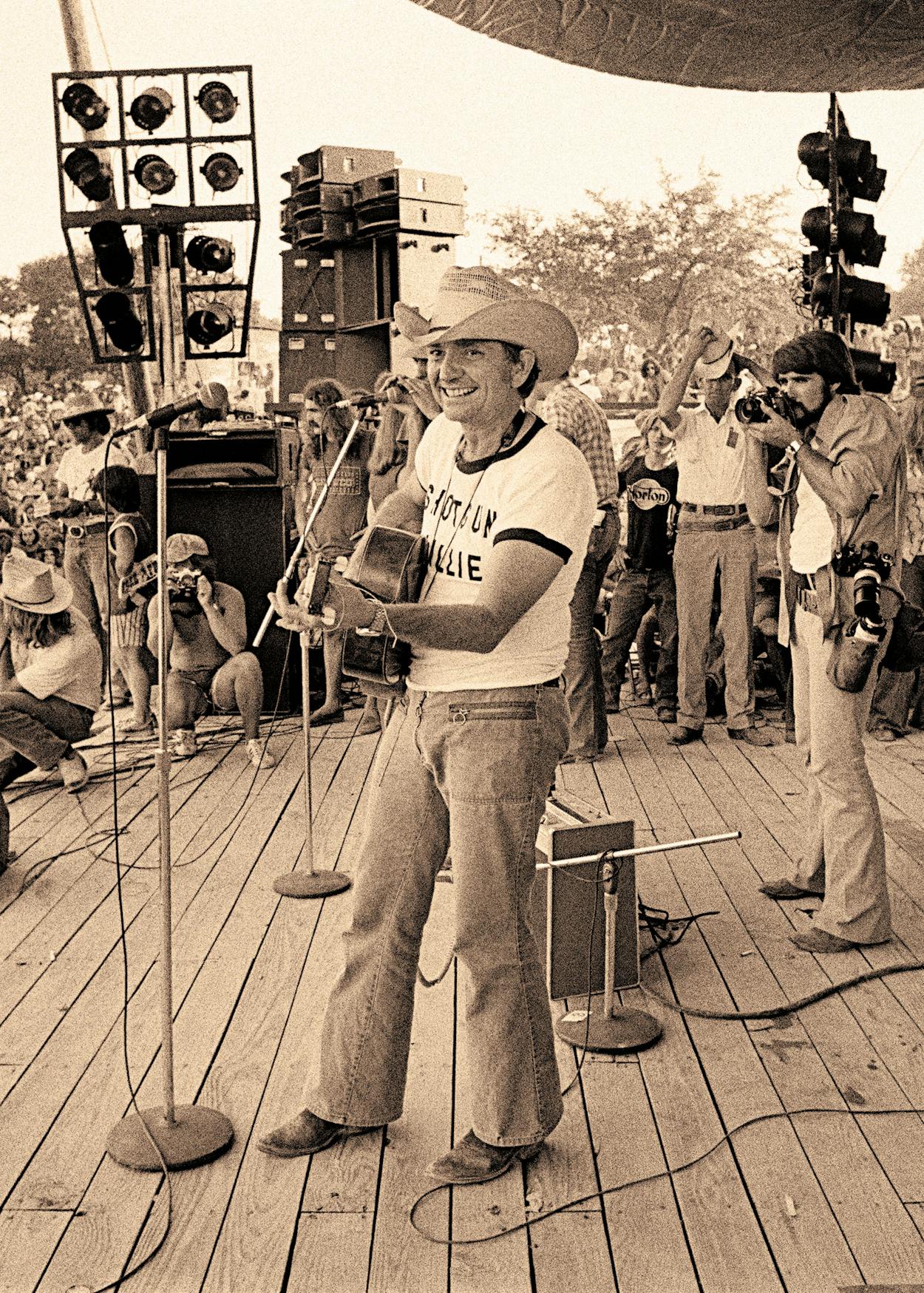

The Dripping Springs Reunion was a three-day country music festival held over the course of a long weekend in March. Its Dallas promoters had high hopes, investing $250,000 in the show and expecting 60,000 people a day. Rolling Stone sent Annie Leibovitz to take photos. But nobody really knew what they were doing, and by the end of the weekend, barely 12,000 people had shown. Worse, since the concert was held in dry Hays County—meaning vendors couldn’t sell beer—the few who did come didn’t spend much money. By any standard measure, it was a colossal failure. But two things happened during the Reunion that would alter the course of country music history. During a backstage guitar pull, Waylon Jennings first heard the songs of Billy Joe Shaver. Even more important, Willie had a good time.

WILLIE NELSON When Woodstock happened, I saw all those folks come together to listen to all kinds of music. I decided that would be a good thing to do around Austin. So we threw the Dripping Springs Reunion, with me, Roy Acuff, Tex Ritter, and so on.

DAVE HICKEY The promoters were old Dallas frat brothers of mine, and I booked the talent, almost all Nashville acts, like Tom T. Hall and Loretta Lynn. The best was Charlie Rich, who just sat in his Cadillac smoking dope and played whenever somebody didn’t show up. But there was also a lot of cultural exceptionalism being felt. We all loved “Texas music.” So I hired songwriters like Billy Joe, Lee Clayton, and Terry Allen, who would go out and fill in the gaps between the big acts.

BIG BOY MEDLIN wrote for the Austin Sun. It was a real culture clash. We all thought, “Wow, look at these rednecks.” Tex Ritter, who emceed, was an asshole. He’d complain about how long it took to change bands: “Maybe if some of these stagehands would get haircuts, they could see the equipment and move it better.” Half the crowd was hippies wanting to dance, and the other was rednecks looking for something else entirely. Even Kristofferson said something to the hippies like “Why don’t you guys sit down and listen one time?”

BOBBY BARE had his first top ten country hit with “Detroit City” in 1963. I played a number of Willie’s picnics, but I don’t think I was at that first one because I remember Billy Joe coming back to Nashville from it and telling me he’d done some peyote or something and just disappeared. He said, “I don’t know what happened, I just wanted to take a walk.” So I decided I’d do the second one.

BILLY JOE SHAVER I got into that dang peyote and got to thinking I was Jesus. I was just walking around, healing people. I baptized a bunch of them.

DAVE HICKEY Billy Joe came out of that Reunion a cult hero because he sang “Black Rose.” It was hillbilly, it was about black people, and Billy Joe only had three fingers. Everybody loved it.

BILLY JOE SHAVER I was in a trailer passing a guitar around and started singing “Willie the Wandering Gypsy and Me.” Waylon bounced over and said, “Whose song is that?” I said, “That’s mine.” And he said, “I’m going to record that.”

ALVIN CROW I went to that Reunion with my mother and father. And it was great. Charley Pride, Hank Snow, Dottie West, Roger Miller. But also an Austin guy, Kenneth Threadgill, who yodeled old Jimmie Rodgers songs. That’s when I realized I needed to move to Austin.

WILLIE NELSON That first Reunion didn’t draw because the promoters didn’t know how to promote it in Austin. They spent all the money in Dallas, the big cities. They didn’t let the local people know where to go. But I saw that it was a good idea. The following year I put on the first Fourth of July Picnic in the same place, and we got 50,000 people.

The Austin scene was coming together. Other songwriters moved in, like B. W. Stevenson, a Dallas folkie with a down-soft tenor who would later have a top ten hit with “My Maria.” Willis Alan Ramsey came from Dallas as well and in the summer of 1972 released his self-titled debut album. It didn’t sell well, but from a songwriter’s perspective, it was a tremendous success; eight of its ten songs would be cut by other artists, including one, retitled “Muskrat Love,” that Captain and Tennille took to number four in 1976. Stevenson and Ramsey, buoyed by the mystique of the sensitive, troubled artist, came to rival Murphey and Jerry Jeff as the town’s top draws. Ramsey later ascended to cult-legend status by failing to produce a follow-up to his debut, which is still his only album.

ROBERT EARL KEEN was a country music fan and college student. I was always a kicker. But even at A&M I realized that one of the best things about College Station was that it was only a hundred miles from Austin. Aggies will throw rocks at me for saying that, but Austin was that cool.

JERRY JEFF WALKER This was earthy. Nashville had been in uniforms. George Jones and his band all wore the same polyester suit. That was changing. We wanted to be the same people on and off the stage.

KANDY KICKER was a DJ at Austin’s KOKE-FM. Battered straw cowboy hats—not felts—with feathered hatbands and Western shirts with pearl-stud snaps, either short-sleeved or with the sleeves torn off. Faded Levi’s and pointed-toe cowboy boots. And for women, really short shorts, torn and faded, with boots.

HERB STEINER B. W. Stevenson was terminally shy. He had a weight problem, he was hairy, and kind of armored against people. But he wanted to be a success so badly that he would do almost anything. He recorded songs he didn’t like but thought would be pop hits. He signed galactically bad management deals. By the time we recorded “My Maria,” he was giving management and agencies 40 percent of his money before he saw anything.

RAY BENSON They were just fooling around in the studio when he wrote “My Maria.” He was pretending to sing like Frankie Valli or Del Shannon in this high, wailing falsetto, and the producer said, “What’s that song?” “We’re just f—ing around.” “Yeah? Well, write that song. We’ll record it next.” So they did.

LEON RUSSELL was a rock star from Tulsa and the co-founder of Shelter Records. I met Willis after I played a show in Austin. I was sitting in my motel room with the door open, and this guy was leaning there with a guitar case. All these people were there, but he didn’t say anything. Pretty soon the people had left and he was still there, so I said, “Do you want to play that thing?” He opened it up and played all these remarkable songs. I decided to record him.

WILLIS ALAN RAMSEY Leon went on a world tour and let me stay in his house in Los Angeles with his recording studio. I got to hang with all these incredible Tulsa musicians but started getting discouraged. I couldn’t get a good sound and became convinced his studio wasn’t that great. Then one night Phil Spector and George Harrison came by to play one of George’s old master tapes. It just sounded so unbelievably good that after they left I remember thinking, “Okay, well, it’s not the studio.”

LEON RUSSELL He had his own ideas about recording. I had gotten [legendary L.A. session musicians] Jim Keltner and Carl Radle to play with him, and Willis was all upset because he felt they were just studio guys. He was always talking about “hard hats” and “real people.” I never could understand what he was going on about.

RAY WYLIE HUBBARD When Willis came back from L.A., it was like a Robert Johnson thing. He’d always just been the kid who hung around. But he showed up at an after-hours jam in Austin and pulled out this Martin D-41, which was the cool guitar, and played Crosby, Stills and Nash’s “Suite: Judy Blue Eyes.” With the licks and everything. Everybody went, “Whoa.”

STEVE EARLE After I heard Willis’s album, I’d hitchhike hundreds of miles to see him play.

As audiences grew, so did the number of places to play, as even some of the old honky-tonks started to open their doors to the new breed of musicians. A more natural fit was the Armadillo World Headquarters, which became Austin’s favorite hippie hangout when it opened in August 1970 and eventually gave the movement its mascot. Then, in the summer of 1972, Murphey wrote the movement’s first anthem—and provided its first sobriquet—“Cosmic Cowboy, Pt. 1.”

BOBBY EARL SMITH Lloyd Doggett [then an attorney running for state Senate] asked us to play a benefit at the Broken Spoke, and we jumped at the gig because we’d been trying to get in there. We packed it on a Monday, a night when it’s usually closed.

JAMES WHITE opened the Broken Spoke in 1964. They drew over five hundred people. And I guess about 70 to 80 percent were hippies. Some of them were barefoot or wearing moccasins or tennis shoes, like a PF Flyer. None of them could two-step. They all did a dance I called the Hippie Hop, jumping around like old hoedown dancing. But there were five hundred of them, and I figured anybody who can draw five hundred people is okay.

EDDIE WILSON When I heard Freda and the Firedogs, I realized what an easy sell country would be to people coming to the Armadillo for some hip rock and roll experience. All the LSD-influenced listening and all the light shows had been too much work. It was exhausting. But beer, dancing, and sweating just went together.

BILLY JOE SHAVER I was booked to play the ’Dillo in front of the Grateful Dead but got there a day late. Eddie was ticked but didn’t make a big deal of it. Actually, he chased me down in the parking lot and said, “Billy Joe, the Dead left you something,” and handed me this roll of toilet paper that had a hit of acid on every square. For about two years, I walked around with that toilet paper in my pocket. I couldn’t hit it every day. I would hit it every other day.

MICHAEL MARTIN MURPHEY There became two camps. There were the cowboy hippie guys who got high and the rest of us who were straighter, or even down on drugs. My band was joking around before a show in New York about “cosmic cowboys.” I knew Jerry Jeff was coming that night, so I wrote the song as a joke for him. It was supposed to be satirical, about the spaced-out cowboys hanging around Austin.

RAY WYLIE HUBBARD I never thought of it as a parody. I thought of it as a battle cry. Murphey would go to these places, play it with his band, and there was this bond. It was like the “Halls of Montezuma” to the Marines. That’s the anthem. That’s who we were.

Progressive Country

The tectonic shift in the scene finally came when Willie moved to town in the summer of 1972. Nobody is clear on the exact moment he made the decision. Some trace it to the night Eddie Wilson took a clean-shaven Willie to see a Murphey–Jerry Jeff double bill in front of a rowdy crowd of long-haired UT students at a club called Mother Earth. Others peg it to a George McGovern rally at Zilker Park that Willie doesn’t even recall playing.

But there’s no disagreement on the effect. Up to that point, the cosmic cowboys had played to crowds that looked largely like they did. Willie brought a different audience; though he’d never made it big as a performer nationally, he’d always been able to fill a Texas honky-tonk. Once he figured out how to bring the hippies and the rednecks together, the scene grew into something no one had seen before. Most folks have always credited that to his innate charisma, to the idea that Austin was the place where Willie was finally allowed to be Willie. But the fact is, Willie came to town with a specific goal in mind: building a scene that would allow him to ignore Nashville completely. And he pulled that off with more than luck and a smile.

DAVE HICKEY Willie would prove to be the hinge. He could hang out with [UT football coach] Darrell Royal and the governor. He brought that real, hard-core constituency.

JIM FRANKLIN was the artist in residence at the Armadillo. He had that intellectual thing that appealed to us hippies. We felt like we’d discovered this jewel hiding in a basket of pigs.

RAY BENSON Willie was like God. We would play with him in Dallas, and the strippers would come and worship him. We’d be sitting there watching as these chicks, the dregs of Greenville Avenue, would come in from the topless joints and say, “Willie, you sing about our life. ‘Night Life’ is about us.”

STEVE EARLE I saw Willie play this joint in Pasadena called the Half Dollar. Pasadena was where the Ku Klux Klan clubhouse was in the Houston area. It was as redneck as Texas got, full of refinery workers who went dancing every weekend. But that night, a bunch of us hippies wanted to sit on the floor and watch Willie play. So as the regulars go around the dance floor, they’re kicking us in the back. Willie stopped in the middle of a song and said, “You know what, there’s room enough for some to dance and some to sit.” That chilled it out.

BILL BENTLEY In June 1972, there was a McGovern benefit in Zilker Park. Several bands played, and then Willie came on. He looked out in that crowd—most of them were hippies—and you could see the realization in his eyes: This is my new audience. The next thing you know, he’s playing the Armadillo.

EDDIE WILSON When I walked into the Armadillo for Willie’s first show, I was stunned. All our hippies were there, but the walls were lined with UT football players.

JIM FRANKLIN The show was such a success that Willie contacted all his buddies in Nashville, guys like Tom T. Hall, Waylon, and Jerry Lee Lewis, and told them, “Drop your projects and come play here. I guarantee you’ll love it.”

TOM T. HALL My show at the Armadillo was the first time I was ever propositioned by a woman. I came out of Kentucky and had this naive notion that men were supposed to chase women. That was the sport of it. So this beautiful, blond-haired girl came out of the audience looking like one of the Dallas Cowboys Cheerleaders. She said, “Hey, you want to go screw?” I said, “Oh, I don’t think so.” The charm had gone out of the thing.

RICHIE ALBRIGHT When Waylon played the Armadillo for the first time, all these hippies and cowboys were just screaming. We had never had a response like that. Waylon turned around and said, “Somebody go get that little redheaded son of a bitch. What’s he got me into?”

JERRY RETZLOFF was district sales manager of Lone Star Beer. [Willie] called one night and asked if I was going to his show at the Country Dinner Playhouse, said he wanted to talk afterwards. “Sure, Will, I’ll be there.” We meet up, and he said, “I think we can work together.” I said, “What do you mean?” He said, “You’re out to make Lone Star appealing to the youth crowd, and I have a problem with them because of the straight country thing. I can’t get the youth market to listen to my old country music because they think it’s what their mothers and fathers are doing. They want to discover their own deal, something rebellious, personal. If we work together, I think we can both overcome our problems.”

WILLIE NELSON Texas young people wanted their own thing. Their parents drank Pearl. They could drink Lone Star and be different.

JERRY RETZLOFF It sounded like a good idea. Then he said, “It’s got to be informal. We’ll trade favors so nothing’s commercial. Deal?” I said, “Right on, Will.” So I started providing the backstage beer.

WILLIE NELSON Back then I had about a $90,000-a-year backstage beer tab. Poodie [Willie’s longtime stage manager, Poodie Locke] and the boys really had a way with the beer.

JERRY RETZLOFF I convinced management on the plan. Back then, the majors—Budweiser, Schlitz, and them—were only buying radio ads in college towns from September to May. So I talked to my marketing boss, who played golf with Willie, and suggested we buy our radio different. That summer, we were the only beer on the radio.

RAY BENSON Lone Star started sponsoring everything. They had a van painted like a six-pack that they took from gig to gig.

WILLIE NELSON I knew what I wanted to do, and a lot of it was working. When Kris and Rita [Kristofferson’s future wife, Rita Coolidge] were filming Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid down in Durango [Mexico], I went down and invited them up. I knew if I brought in people like them and Leon Russell, it would be good for whatever we were trying to do.

MICKEY RAPHAEL was Willie’s harmonica player. Willie had seen Leon play and wanted to appeal to that younger audience.

WILLIE NELSON I knew his work on Joe Cocker’s Mad Dogs & Englishmen album, and that he was the real deal. I didn’t have any doubts about how everybody would get along. Anytime you can work someone else’s fans, that’s good. He gets ours, we get his, and next thing you know it’s quantum physics going on.

Another focus of Willie’s strategizing was radio station KOKE-FM. On New Year’s Eve 1972, KOKE switched to a new format geared to the mixed crowds he was pulling at the Armadillo. Programmers at the station, which was housed in a little walk-up near a gun store on North Lamar, first thought to call the new format “country rock.” Realizing they’d never be able to sell “rock” to country advertisers, they settled on the term “progressive country.” Willie was a regular on-air presence, showing up unannounced to pick his guitar and spin records. Billboard named KOKE the most innovative station in the country for 1974.

NICK SPITZER was a DJ at KOKE and a graduate student in folklore at UT. I’d play the Carter Family doing “Give Me the Roses While I Live,” a kind of moral, Victorian tale, and segue into the Rolling Stones’ “Dead Flowers,” which is about this dissolute individual in the basement with a needle and spoon who’s not long for the world. And then I’d come back with some Texas dance-hall music.

JIM RAY was general sales manager at KOKE. It was all tongue-in-cheek, high theater. Our symbol was a long-haired cowboy roping a goat. We called him Super Roper.

GARY P. NUNN One DJ was a Hispanic kid whose radio name was the Sinsemilla Kid, sinsemilla being Spanish for “no seeds.”

NICK SPITZER There was never a feeling of “We’re educated, they’re rednecks.” We did get a kick, though, when Robert Altman’s film Nashville came out, and [mainstream country station] KVET bit hook, line, and sinker, like it was a big documentary. They did a remote from the theater saying, “Come see the great Nashville revealed in this fine new film.” And then people went in and saw this surreal, despondent breakdown of the culture.

KEN MOYER was the station manager at KOKE. Willie liked to play at the landing atop the spiral staircase in our foyer. We did concerts the night before the July Fourth picnics. He did a New Year’s Eve broadcast once and brought Kristofferson, who leaned up against the transmitter switch and knocked us off the air.

CARLYNE MAJER owned Soap Creek Saloon, which she opened just west of town in February 1973 with her husband, George Majewski. Doug Sahm had a huge hit on KOKE with Freddy Fender’s old song “Wasted Days and Wasted Nights.” At the end of it, Doug said, “That’s for Freddy Fender, wherever you are.” So I found Freddy in Corpus and brought him to Soap Creek to play with Doug’s band. I’ve never heard such swooning in my life.

JOE NICK PATOSKI It was hilarious. Corpus knew something was going on in Austin, but their interpretation was goofball. Freddy shows up wearing a long leather jacket with Western fringe, looking so out of place. But he sings his ass off.

BILL BENTLEY Right after that, Doug’s manager, Huey Meaux, starts managing Freddy. Huey finds “Before the Next Teardrop Falls” for him and has him recut “Wasted Days.” Both became huge national hits.

Back in Nashville, Waylon was poised to take advantage of the shifting terrain. RCA had lost Willie, and the label didn’t want the same to happen with Waylon, who was an easier sell to traditional country listeners. He’d come out of the West Texas rock and roll scene, but Chet Atkins had smoothed over that aspect of his sound. Waylon restored it in 1973, with his first self-produced album, Lonesome, On’ry and Mean, and an appearance at the New York underground art-scene hangout Max’s Kansas City. He was thought to be the first country performer to play a rock nightclub in the city, at a time when New York didn’t even have a country radio station. Later that year he followed those triumphs with a collection of Shaver songs, Honky Tonk Heroes.

RICHIE ALBRIGHT When Waylon’s contract was coming up, RCA offered him $5,000, and that made him mad. He wasn’t the kind to hold anything back, but he’d gotten the yellow jaundice and was sick, so I told him to talk to this guy I met in New York, Neil Reshen, who managed Miles Davis. That was the big turnaround. Neil got Waylon artistic control.

DAVE HICKEY Waylon wasn’t really a badass, but he was smart, with enough self-consciousness and irony about his persona to make people comfortable. At Max’s Kansas City, he played until four in the morning, and everybody was still there at the start of the last set. You could have killed every Texan in New York if you had a small bomb. Waylon finally got up to the microphone and said, “If y’all could give us a few minutes more, we’re waiting for our pills to go off.”

BILLY JOE SHAVER Waylon ducked and dodged me for six months after saying he’d cut my song at that Dripping Springs Reunion, until one night I found him in a studio. I was in this hall full of groupies and bikers, and Waylon got wind I was there and sent a $100 bill folded up in a little square with a message for me to take off. I said, “Tell Waylon to stick that up his ass and twist it.” So here he comes, pissed, with bikers on each side. And he says, “Hoss, what the f— do you want?” I said, “You told me you were going to listen to my songs. Actually, you told me you were going to record one.” Then I threatened to whip his ass. Maybe that tickled him because he gave me a listen. By the time I got to “Honky Tonk Heroes,” he slapped his knee and said, “I know what I’m going to do.” Then he cut them all, with his own band. Chet had a fit about it.

RICHIE ALBRIGHT When we were recording “Honky Tonk Heroes,” Waylon wanted to cut just the front, slow part of the song first, then later do the part where it picks up. Billy Joe was there and when he heard us stop, he goes nose-to-nose with Waylon. “You are f—ing up my song!” Waylon says, “Just let me show you what we’re doing.”

In August 1973, Jerry Jeff recorded his next album, ¡Viva Terlingua! The idea for the record came to him while he was walking past New York City’s Town Hall, an old community meeting center turned performance space. He saw a motor home parked in front with cables running out and through a building window and asked what was up. Inside the vehicle were sound engineers cutting a record. He invited them to the Hill Country ghost town of Luckenbach, with plans to turn its nineteenth-century dance hall into a studio where he could rehearse during the day and record at night. He also summoned the Lost Gonzo Band—the name Murphey’s band now used when backing Jerry Jeff—promising he’d have microphones hanging in the trees.

JERRY JEFF WALKER The engineers spent a week getting everything set up. It was a great atmosphere. You’d look out from the dance hall at trees and birds. Then they said, “Let’s go!” And I went, “I don’t have any songs.” I’d been too busy dreaming everything up. But I had pieces of things. I had part of “Gettin’ By,” and that’s about a happy-go-lucky guy, so I didn’t need to get too deep or wordy on that. “Sangria Wine” was a party song. Guy Clark had played me “Desperados Waiting for a Train.” That’d be my story song, the “Bojangles” of the project.

RAY WYLIE HUBBARD I’d begun “Up Against the Wall, Redneck Mother” one night in this redneck bar in Red River [New Mexico]. Somebody had started in on me: “How can you call yourself American with hair like that?” Then I’d seen a pickup outside with a bumper sticker reading something like “America, love it or leave it.” Later that night, B.W. and Bob Livingston and I were passing a guitar around, and I started singing, “He was born in Oklahoma . . .” I came up with a chorus, we laughed, and that was it. Next thing I know, Livingston calls me from Luckenbach and says Jerry wants to cut it. But there was no second verse. I made it up on the phone.

HERB STEINER Some of us took acid one day and then worked up “Wheel.” “Wheel” is us on LSD.

JERRY JEFF WALKER About Wednesday I thought, “Why don’t we get some people down here Saturday night and do part of this live?”

JIM RAY He needed an audience and called KOKE. They spent fifty bucks and we ran ten spots or so and got him a hell of a big crowd.

GARY P. NUNN Jerry Jeff looked at me onstage on Saturday night and said, “Sing that song you were playing this afternoon, the one from London.” See, when “L.A. Freeway” had gotten some West Coast buzz, the band hit the road with Jerry Jeff, but I went to England with Murphey to promote his Cosmic Cowboy Souvenir record. He was married to an English girl, and while he was out doing promo stuff, I crashed at her brother’s London flat. It was cold. The heat would go off in the morning and not come back on until evening. Here came a first line: “Well, it’s cold over here, and I swear, I wish they’d turn the heat on.” So I made up a silly little song, trying to mix British and Texas phrases together. “You can put up your dukes or bet your boots.” I had no idea that I’d ever do anything with it.

JERRY JEFF WALKER This was the first time we ever did the whole song, and the audience couldn’t even hear Gary on the verses. But when we got to that chorus, things snowballed. Everybody went nuts.

GARY P. NUNN Afterwards, the guys from the recording truck came running in. “Hey, we weren’t ready for that. You’ve got to do it one more time.” So I had to go back to the low spot where the song begins. I said, “Gotta put myself back in that place again.”

STEVE EARLE I saw Jerry Jeff with the Gonzos right after they recorded ¡Viva Terlingua!, and they were like the Band, trading instruments on different songs. It was clear they were now his band. About that time, Murphey moved to Colorado.

MICHAEL MARTIN MURPHEY I’d spent a few months unable to sing because I’d had nodes shaved off my vocal cords. We kept rehearsing, but the recovery took too long. Then the band made ¡Viva Terlingua! Other albums had been important to the scene—my record Cosmic Cowboy Souvenir was the first to directly address what was happening in Austin. But ¡Viva Terlingua! wiped out everything else.

By mid-1974, Austin had a national reputation, thanks largely to the reporting of Rolling Stone stringer Chet Flippo, who seemed to get a dispatch from the Armadillo into every issue. Inspired by the failed Dripping Springs Reunion, Willie had hosted his first two Fourth of July picnics—one in Dripping Springs and one in College Station, both headlined by Leon Russell—which were considered sufficiently cool for NBC to send legendary DJ Wolfman Jack and a film crew to record the College Station picnic for the music program The Midnight Special.

Another boost came with the publication of The Improbable Rise of Redneck Rock, by journalist Jan Reid. The book, which grew out of a TEXAS MONTHLY article, became required reading for kids like Robert Earl Keen, then an A&M freshman, who still refers to it as “the playbook.” It also wound up in the hands of Bill Arhos, the director of programming at Austin’s PBS station, KLRN, inspiring him and producer Paul Bosner to create a weekly TV show spotlighting the scene, Austin City Limits. In November 1974, they shot a pilot with Willie. The performance was marked by an unmistakable rapport between band and audience that implied that this kind of thing happened every Friday night. The show, which aired around the country in early 1975, was a hit, and PBS ordered a full season, to be funded in part through a generous sponsorship from Lone Star Beer.

TOM T. HALL The picnics were a real adventure. It was Willie, Waylon, Bare, Kristofferson, Billy Joe, just a whole bunch of us in a little trailer dressing room. Can you imagine being in a mobile home with that crowd? They all had that hair and Indian charms for necklaces. I was in khaki britches, goosey loafers, and an Izod golf shirt. Everybody probably thought I was a lawyer. But then I got so caught up in the excitement that when my set was over, I threw my guitar into the audience.

CARLYNE MAJER I was stage manager at College Station, and [my husband] George was in charge of carrying naked women off the stage. He would scoop them up, put his nose right in their chest, and run them down the steps to the front. He was a busy man.

GEORGE MAJEWSKI The show was running over one night, and Carlyne had to tell David Allan Coe he couldn’t go on. She found his manager, and then he told Coe, “The law is coming. They’re looking for you.” Coe hopped on his bus and left.

JERRY RETZLOFF We didn’t get rid of Kinky [Friedman] that easy. He stood on the steps with his guitar trying to get onstage.

WILLIE NELSON A lot of acts were pissed because what’s-his-name, Kung Fu, got to go on—David Carradine. What was funny too was that Kung Fu, David, was out there barefooted. So I said, “If he can go out there barefooted, I’m going out there barefooted,” and took my shoes off. In the meantime, people had thrown a bunch of roses with thorns onstage; I walked right over the goddamn things. I thought, “Maybe I’m not as tough as Kung Fu.”

BILL ARHOS That first year of Austin City Limits was crazy. Doug Sahm was on, and the air in the studio turned purple from marijuana smoke. I had to throw a guy out for spraying silver paint up his nose. Seriously. And God, Jerry Jeff was supposed to tape one night, but he’d gone to Miami to see the Cowboys play in the Super Bowl. If they’d won, he would’ve never shown up. But they lost, and he came, walking onstage while the Gonzos were singing “London Homesick Blues,” just grinning like an idiot. I said, “What the hell?” And someone said, “There’s a guy in the audience wearing a gorilla suit.” There was.

Outlaws

For all of Willie’s foundation laying, and all of the fun he was having, there was still something missing: a hit. The two post-Nashville albums he’d recorded for Atlantic, 1973’s Shotgun Willie and 1974’s Phases and Stages, had been satisfying artistically and critically, but both sold poorly. That was about to change. Waylon’s manager, Neil Reshen, began managing Willie too, and he got Willie a deal with full artistic control from Columbia. For four days in January 1975, Willie worked in a recording studio with no producer watching over him, for the first time in his career. The record he made was Red Headed Stranger. Released in June 1975, it became his first number one country album and stayed on the country chart for two and a half years. It also spent nearly a year on the pop chart. Suddenly the crowds of two thousand he’d reliably drawn in Texas mushroomed to twenty thousand—across the country.

BOBBY EARL SMITH Joe Gracey [KOKE’s program director] and I went by [sound engineer] Phil York’s studio in Garland. As we pull up, Bee Spears [Willie’s bassist] walks out looking all beat-up. He’d been living in there with Willie for days. He said, “I’m going back to Austin.” We walk in, and Phil says we’ve got to hear what Willie cut. Now usually, when you’ve just wrapped something, you’re sick of it, you don’t want to hear it for a while. So we said sure. He said, “Let me back it up. You have to hear it from the beginning. It tells a story.” When it got to “Blue Eyes Crying in the Rain,” I almost fell on the floor. I thought, “God, that’s the prettiest thing I’ve ever heard.”

BOBBY BARE That record was priceless. It was what every Willie Nelson fan wanted, bare-bones Willie. The people running Columbia didn’t want it to come out in the worst way. Said it sounded like a bad demo.

BILL BENTLEY I wrote a review of Red Headed Stranger for the Austin Sun saying I didn’t get it. It sounded like they made it in a minute. But after I turned that in I went home, got stoned, and listened again. I was floored. You couldn’t listen to it like it was country music, especially of the seventies. It was almost folk music, completely stripped down. Luckily I knew how to use the typesetting machine. I went back to the Sun that night, wrote a different review, and snuck it in.

BOBBY EARL SMITH Gracey started playing the shit out of it on KOKE, especially “Blue Eyes Crying in the Rain.” And that song started getting played all over the country. Here comes the legitimacy that’s always been just out of reach. Willie’s got a hit. A monster hit. It paid off for the whole community. Everybody loved “Blue Eyes,” in farming communities, everywhere. Suddenly it didn’t matter who had long hair.

Finally, Nashville executives took an interest in what was happening in Texas. And being blessed with more marketing savvy than the songwriters, DJs, and journalists who’d previously tried to describe the new country, they gave it a name sexy enough to sell. In January 1976, RCA released Wanted! The Outlaws, a collection of previously recorded tracks—many already released—by Willie; Waylon; Waylon’s wife, Jessi Colter; and Tompall Glaser, a moderately successful singer who ran an independent Nashville studio. The record was a smash, and the ensuing outlaw craze boosted not only Willie and Waylon but also artists like Hank Williams Jr., Johnny Paycheck, and David Allan Coe, and even some Austinites, like Jerry Jeff.

BILL MALONE Nashville tried to hold all this at arm’s length. It took them a good while to accept it.

RICHIE ALBRIGHT RCA had already relented on creative control, and now they were ready to make some money. And they did. Hell, Wanted! The Outlaws was the first country album to ever go platinum.

BOBBY BARE RCA came up with that “outlaw” term out of the clear blue sky. But Neil Reshen ran like a dog with it, even though Waylon was so far from being an outlaw. What he was, was a good-hearted, good ol’ boy who just happened to do drugs. When I met him, it was pills every day, until he jaundiced out and wound up in the hospital. Once he got his color back, he went to Hollywood and got turned on to coke, and then he was off and running. He started to buy into the outlaw thing, began thinking he was that guy.

RICHIE ALBRIGHT We were producing Hank Jr.’s The New South, and there’s a knock on the door. Waylon was overdubbing a harmony at the other end of the studio, Hank’s sitting on the couch, and the DEA walked in the control room and said they had been following a package. Well, it had gotten there maybe ten minutes before they did, and it was cocaine; Waylon had it in the studio. So I leaned on a button so he could hear what was going on in his headphones. They had a search warrant for the office, but not the studio, so I said, “You can’t go in that room because we’re overdubbing. This costs us $300 an hour, and we’re gonna keep working.” Then I went in, winked at Hank, and said, “We’re going to have to go back and do that line again.” Then I found the bag, put it in my pants, slipped off to the bathroom, and took care of it.

WILLIE NELSON Everybody I worked with was an outlaw in some way or another. But I don’t think any of us were robbing banks.

RICHIE ALBRIGHT The next day Waylon was booked for possession, and that was big news in Nashville. And it was funny because Willie played in Nashville that night and had Waylon come out onstage. The place went nuts. The day after that, we were at the lawyer’s office, and Waylon said, “You got a guitar around here?” They did. He said, “You’ve got to hear this new song.” He started playing “Don’t You Think This Outlaw Bit’s Done Got Out of Hand.” He got to the part where he says, “They got me for possession of something that was gone, long gone,” and the lawyers faces all drained. They said, “You can’t say that.” Waylon goes, “Hell, it is gone.”

While Waylon and other Nashville stars adopted the outlaw mantle as a means of climbing the charts, most Austin musicians dismissed it as a cynical pose. In fact, the real outlaws happened to be back in Texas. One of the characteristics of a regional music business was that the players, operating out of the glare of the big media centers, often made their own rules. These were people who’d given Willie gigs through the lean years of his career, and he remained deeply loyal. As he rose, they rose with him, the joke being that the only disqualifier for getting on his bus was mistreating old people or children. Two of his more colorful consorts were his drummer, Paul English, who’d also served as Willie’s money collector with stingy club owners, and a mercurial Dallas promoter named Geno McCoslin.

MICKEY RAPHAEL I was riding in an elevator in L.A. once with Paul, and he had on his black cape with red satin lining that went all the way to the floor, black pants and shirt, and red patent leather cowboy boots. The door opens up, and standing outside is Little Richard in the same getup—but his cape only comes to his waist. Paul doesn’t even look at him, just struts out like he’s the Prince of Darkness. But Little Richard does a double take.

TIM O’CONNOR co-owned the Castle Creek night club in Austin before going to work for Willie. I was walking backstage at the picnic at Liberty Hill, and it was raining really hard. All of a sudden you heard BLAM! BLAM! BLAM! BLAM! Everybody hit the deck, and I said, “It’s just Paul and his pistol.” He needed to get the water off the stage roof, so he blew some holes in it.

RICHIE ALBRIGHT Guns? That’s just the way it was, especially if you were the guy handling the money.

WILLIE NELSON If you didn’t have a gun, we’d give you a gun.

RAY WYLIE HUBBARD Geno was my manager when I was the house band at 57 Doors, in Dallas. I’d go in there to get paid, and there’d always be a gun and money on the table.

FREDDY FLETCHER is Willie’s nephew. Geno was a rough customer. At the Gonzales picnic, one of Willie’s bodyguards was a big-deal Hells Angel, and he and Geno stayed in a house a couple of weeks prior, getting the site ready. But they didn’t get along. One day Geno ran over the guy’s Harley. Literally. So the guy started screaming, and Geno just pulled a gun on him. He took him up in a helicopter and told him he’d have to jump. This badass Hells Angel turned into a crying puddle.

RAY WYLIE HUBBARD When I played the College Station picnic, I stopped by the hotel to pick up my credentials. I walk in the room and Geno has a turntable with a Waylon Jennings record playing. And he’s on the phone calling up radio stations saying, “Yeah, we’re out here at the site, Waylon’s onstage right now, and listen, I really can’t confirm that Bob Dylan is here. And we think John Lennon is going to sit in, but we don’t know that. Okay, I gotta go.” And then he’d call another radio station, get on the air, and do the same thing.

RAY BENSON We were filming a show at the Alliance Wagon Yard, and I’m in the video truck with a guy from CBS Records named Herschel. I put my hand on the board and suddenly go, “Ow! Was I just shocked?” and then Herschel goes, “Ow! My leg!” and I turn and see his jeans going dark with blood. One of Willie’s guys had shot at Joe Gracey’s brother with a .22, and the bullet went through the side of the van, grazed my left hand, and then went into Herschel’s leg. But when CBS found out who shot him, they decided not to press charges. They didn’t want to alienate Willie.

LEON RUSSELL That was my video truck. But I figured that if you send your million-dollar truck down to Austin, you’ve got to expect to get a bullet hole or two in it.

Nashville’s outlaw sales pitch didn’t leave much room for the cosmic cowboys, but by that time there wasn’t much room for them in Austin either. Scenes built around the taste of young people tend to shift as the kids grow up and new ones move in. So went Austin. Murphey had become a pop star on the strength of his song “Wildfire,” which went to number three on the Billboard Hot 100, and was happily doing his own thing in Colorado. The Jerry Jeff party continued to rage, but it was as likely to take place at New York’s Lone Star Café as in Austin. Willie played regularly at the Texas Opry House, a venue half a mile south of the Armadillo that he’d taken over. But he was too big to be considered part of any local scene. Waylon never moved to Austin, but Jimmie and Stevie Ray Vaughan did, and suddenly the dominant sound was the blues. Still, Nashville talent scouts kept combing the weeds of Austin for the next Willie.

BILL ARHOS By the time we got ready to tape the 1977 season of Austin City Limits, the scene was gone. We started booking national acts.

MICKEY RAPHAEL As Willie became mainstream, local acts started getting signed. But Nashville never really got it. They tried to mold the music.

RAY WYLIE HUBBARD We recorded an album for Warner/Reprise, but then while we were on the road, somebody at the label said, “This is a folk-rock record. Country radio is not going to play this.” So they put girl singers and steel guitars on every track and just broke our hearts. I called my lawyer and said, “They put rope letters on the cover of the album. What can I do?” He said, “I suggest you start drinking.” So I did, for about the next twenty years.

BILL BENTLEY The thing that turned Austin inside out was cocaine. The city got flooded with it.

STEVE EARLE It created a caste system. The democracy goes out when people are hiding in bathrooms because some can afford cocaine and some can’t.

WILLIE NELSON I never liked it. Eventually I told everybody, “You’re wired, you’re fired.” If you’re going to play music, you better all be on the same drug. You can’t have a guy up here wailing away on cocaine while you’re laid back on a little pot. It just don’t work.

MICKEY RAPHAEL Man, I go back and listen to some of the live recordings from those days, and on songs like “Stay All Night” and “Bloody Mary Morning,” we’re playing two hundred miles an hour. Willie would turn around and look at us like, “Where’d you guys go?”

FREDDY FLETCHER Austin went from the peace and love of the sixties to something with a much harder edge.

JAN REID I did a TEXAS MONTHLY story called “Who Killed Redneck Rock?” I wrote that they were taking the outlaw shit too seriously, that Willie had a Hells Angel working for him who was known for pistol-whipping. What’s that guy doing hanging out with Willie? The guy was pissed at me. Unfortunately, a guitar player in town named John Reed was playing some blues place and became the victim of a severe case of mistaken identity. The band took a break, and suddenly this hulking guy was throwing him around the room.

JOE NICK PATOSKI When [the Austin blues club] Antone’s opened, in 1975, the first thing you noticed was that everyone was dressed up. Clifford Antone took great pleasure in buying nice oxford shirts for his employees. The whole idea was that they weren’t that cosmic cowboy shit.

ROBERT EARL KEEN When I finally got out of A&M, I decided to find myself as a songwriter, and my plan was to go to Austin, hang out at the Armadillo, and be a cosmic cowboy. I made an exploratory trip down, and the first thing I did was walk into Ray Hennig’s music store and run into Mickey Raphael. I thought, “Wow, I’m on a fast track to cosmic cowboy stardom.” And then I moved to Austin, and it’s like they shut all the doors and closed the saloon.

JOE NICK PATOSKI The Summer of Love in San Francisco in 1967 marked a huge cultural shift. But when you look back on it now, the psychedelic music that came out of it had a pretty brief run. What started in Austin in that fuzzy 1970 to 1973 period is still playing out. There’s a continuity that you can’t say about any other regional music explosions in the United States in the latter half of the twentieth century. And that ain’t blowing smoke. The singer-songwriter tradition is linked directly. The whole idea of neo-traditionalist country was articulated by Asleep at the Wheel and Alvin Crow rediscovering western swing. The Americana format, and all that stuff that people call Texas music, it all came out of Austin.

STEVE EARLE I DJ a show on that Outlaw Country channel on Sirius, and there are things I hate about the whole outlaw idea. I don’t think I do the same thing as Hank Williams Jr. or David Allan Coe. But I do the same thing as Guy Clark and Willie Nelson. So what’s lasted of that time and place that’s real? For me, it’s the music. I still listen to all of it.