When Texas Monthly set out to create a special issue celebrating Willie Nelson, we knew it wouldn’t be enough just to assign new stories, comb our archives for favorite old profiles, or even rank and review all 143 of Willie’s albums. So we reached out to some two dozen of Willie’s longtime friends, fans, and collaborators and asked them to share one favorite Willie story. From “Whiskey River” writer Johnny Bush’s memory of a portentous moment on tour with Willie back in 1962 to current producer and songwriting partner Buddy Cannon’s description of what it’s like to work with Willie right now, this collection of anecdotes offers an inside look at what Willie’s like when the spotlight shuts off.

Johnny Bush

is a singer-songwriter from San Antonio who played drums with Willie’s road band in the sixties and later wrote “Whiskey River,” which became Willie’s signature show opener.

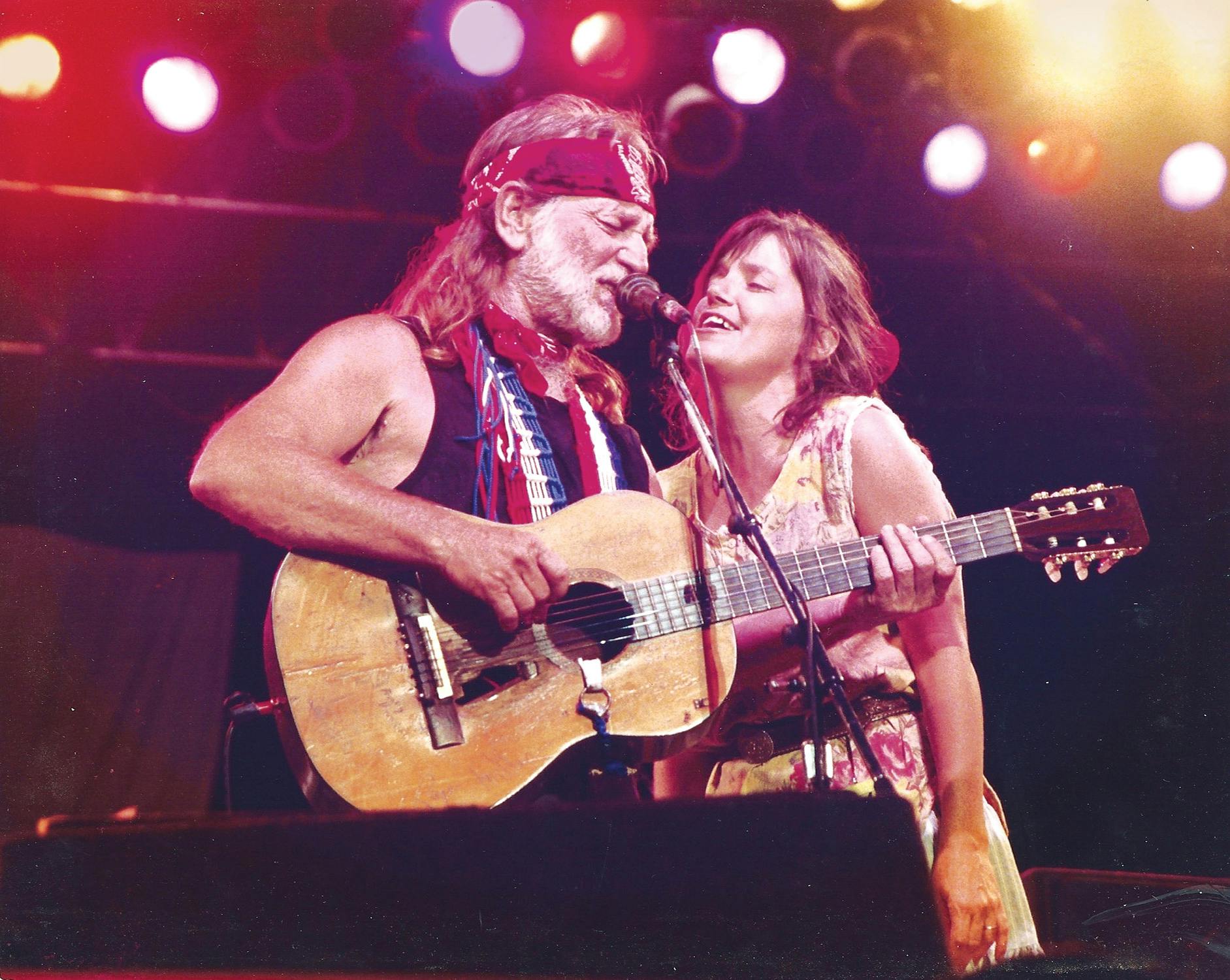

Willie had really come into his own as a songwriter [by the early sixties], and he put a band together to go out and play. It was Paul Buskirk on guitar, Jimmy Day on steel, Shirley Collie singing with him—before they got married—and myself on drums. And we were going to play two weeks at the Golden Nugget in Vegas. This was the big time.

The guy running the Golden Nugget at the time was named Bill Green, and he sent his flunky down to the motel. I was sitting on the floor in Willie’s room when he came by, and he said, “Mr. Green wants the big guitar player”—that’s Buskirk—“to play on the right side of the bandstand. And he wants the girl singer onstage at all times; he doesn’t want you calling her out.” And he had several other changes he wanted Willie to make. When he was finished, Willie said, “Are you through?” And the guy said, “Yes.” And Willie said, “Then go tell Mr. Green that my show is going to stay like it is, and my career will survive—with or without the Golden Nugget.”

I nearly fainted. This was our big break, the Golden Nugget. I’d already gotten to thinking about all the money we were fixing to make, and it was flying right out the window. Had it been me, I would have agreed to every one of those changes. They weren’t that bad. But that’s just Willie. It’s the way he is now, and it’s the way he was when we were driving around the country in a ’46 green Ford with the gas tank on empty.

Jeannie Seely

is a singer-songwriter whose biggest hit, “Don’t Touch Me,” won a Grammy in 1967. Her weekly radio show, Sundays with Seely, airs on Willie’s Roadhouse on SiriusXM, Channel 59.

When Willie was recording for Liberty Records in L.A. in the early sixties, I was working as a secretary at the record label. One of my jobs was to rent out office space in the building, and Willie took some because he wanted to open a West Coast publishing office. I’d go up there on my lunch hour and tell him where all the studios were, answer any questions, help him any way I could.

Years later, he was working on a movie script—he still insists he’s going to get it done one of these days—and he read a part to me that was set in that old office. I just looked at him; I was so surprised. And he said, “Well, you didn’t think I’d forget, did you?” No, Willie Nelson doesn’t forget anything.

About ten years ago, I lost my home, my car, and everything in the big flood in Nashville. The Opry was flooded too, so really, I lost two homes, and I ended up being all over the news. The Associated Press came down and talked to me, and so did some TV reporters. They showed my beautiful Martin guitar, just destroyed, on top of a pile of stuff.

One of the first calls I got was from Willie. He said, “Well, I saw on the news that the flood floated your mailbox away. So where do I send my check?”

Charley Pride

is recognized as country music’s first African American superstar. According to legend, when the two men played a show together in Texas in 1966, Willie moved to preempt any hostility from the audience by walking onstage and planting a kiss on Pride’s mouth. Pride went on to have 29 number one country singles and was inducted into the Country Music Hall of Fame in 2000.

I don’t know of any artist who was against me because of my uniqueness in the business. The thing that caused me a lot of harm back then was that club owners were afraid to book me. They said they didn’t want any incident. I’d tell them, “I’m in complete agreement with you on that.” Eventually, they decided they could put me on shows with bigger artists like Ray Price or Buck Owens, and just push me out there. At first, the audiences would be shocked. RCA hadn’t released any pictures of me; the audience didn’t know what I looked like. But the minute I started singing, it didn’t make any difference.

Willie was big in Texas, so we booked some package shows down there, and that’s when he gave me The Kiss. He always says it was at Dewey Groom’s Longhorn Ballroom in Dallas, but I remember it being at a Rodeway Inn down near Austin. And to be honest, I don’t know if it helped with the audience or not. I know nobody got mad about it. But I told him at the time, “I’m going to get you back one day.”

And he just kept telling the story everywhere, to everybody. “I kissed Charley, and he liked it.” Well, I don’t remember it being that good. But you know Willie. He throws all those little things in there like that. Finally, I got even. Years later, we were playing Billy Bob’s in Fort Worth, and I said, “I’ve been waiting for this,” grabbed him, and kissed him. Then on his birthday this year, April 29, I sent him a present with a note that said, “Happy birthday, but I don’t think I need any more kisses.”

Don Roth and Jan Reid

“The Coming of Redneck Hip,” adapted from the archives: November 1973

Ten years ago Willie Nelson wore business suits for his national television appearances; for the April 7, 1973, Armadillo World Headquarters audience in Austin he was a little looser: boots, beard, cowboy hat, and gold earring. Nelson may look different, but except for the addition of some rock licks and lyrical references to Rita Coolidge’s cleavage, his music hasn’t changed all that much. His old songs—“Hello Walls,” “The Party’s Over,” “Yesterday’s Wine”—still evoke memories of beery nights and jukeboxes, but they blend nicely with the newer, more upbeat numbers. Onstage, Nelson accepts praise with an irresistible smile, yet never lets audience enthusiasm interfere with his standard act, a nonstop, carefully rehearsed medley of his own tunes.

As remarkable as Nelson’s act that night was his audience. While freaks in gingham gowns and cowboy boots sashayed like they invented country music, remnants of Willie’s old audiences had themselves a time too. A prim little grandmother from Taylor sat at a table beaming with excitement. “Oh lord, hon,” she said, “I got ever’ one of Willie’s records, but I never got to see him before.” A booted, western-dress beauty drove down from Waxahachie for the show, and she said, “I just love Willie Nelson and I’d drive anywhere to see him . . . but you know, he’s sure been doin’ some changin’ lately.” She looked around. “I have never seen so many hippies in all my life.”

The crowd kept pressing toward the stage, resulting in a bobbing, visually bizarre mix of beehive hairdos, naked midriffs, and bare hippie feet. An aging man in a sport coat and turtleneck stubbed out his cigar and dragged his wife into the madness, where she received a jolt she probably did not deserve: a marijuana cigarette passed in front of her face. A young girl, noticing the woman’s discomfort, looked the woman in the eye, and took another hit.

But Nelson’s music relieved any cultural strain that developed beneath him. He played straight through for nearly two hours, singing all his recorded songs, then starting over. They handed him beer, threw bluebonnets onstage, yelled, “We love you, Willie”—a sentiment he returned when he finally called it quits: “I love you all. Good night.” A night that for many had been a sort of hillbilly heaven, though Tex Ritter would have undoubtedly taken issue with the form.

Don Roth is the executive director of the Robert and Margrit Mondavi Center for the Performing Arts, University of California–Davis. Jan Reid is a longtime Austin journalist and author of the 1974 book The Improbable Rise of Redneck Rock, among others.

Richie Albright

is Waylon Jennings’s former drummer.

When Waylon played the Armadillo for the first time, all these hippies and cowboys were just screaming. We had never had a response like that. Waylon turned around and said, “Somebody go get that little redheaded son of a bitch. What’s he got me into?”*

*Excerpted from “That ’70s Show,” by John Spong (Texas Monthly, April 2012).

Ray Wylie Hubbard

is a singer-songwriter who lives in Wimberley. He has released eighteen albums, starting with 1976’s Ray Wylie Hubbard and the Cowboy Twinkies.

Geno McCoslin was a promoter in Dallas who booked Willie in the Western Place in the early seventies. But when Willie grew his hair out, the Western Place fired him. It was right about the time Shotgun Willie came out, and pretty soon, Geno opened a place called 57 Doors. About eight blocks from there, he had a house where he’d put bands up and have parties. I’d never met Willie, but I knew Geno, so I was at that house one night—with a dancer in one of the bedrooms. All of a sudden, the window opens, and this guy comes crawling through. He says, “I forgot my key,” and just walked on through. Well, I came out a little bit later and saw him, and he said, “Man, I’m sorry,” and I said, “Wait, you’re . . . ” And he said, “Willie Nelson.” And I said, “Oh, okay. You’ve grown your hair out.” That’s the first time I met him.

After that, I started hanging out with him. I had an apartment in Dallas, with one of those deals where visitors would call from the gate, and you’d buzz them in. About three o’clock one morning, it starts going off. So I say, “Who is it?” and then I hear, “It’s Paul English, Poodie Locke, and Michael Gene Schroeder, let us in.” Paul, of course, was Willie’s drummer. And Poodie and Michael Gene were part of the road crew. But if you asked them what they did, they’d always say, “We’re Willie’s liaisons.”

Against my better judgment, I let them in. They came up and said, “What are you doing?” I said, “Well, nothing.” They said, “We’re going to a beer fest in Milwaukee. But first we gotta meet Willie and the bus in Garland at six a.m. We got three hours to kill, so we thought we’d come visit.” Then at about five a.m., Paul says, “Come on, Ray, come with us to Milwaukee.” I said, “Man, I can’t. I’ve got tickets to see the Eagles. There’s this girl I’m trying to sleep with who loves the Eagles.” And Paul goes, “Ah, you don’t want to see the Eagles. They sound just like their records.” Next thing I know, Michael, Gene, and Poodie pick me up, carry me down the stairs, take me out to Garland, and we get on this old bus.

It was Willie’s first bus. He called it the Time Tube because, as he explained it, “When you get on there, time passes somewhere else.” So now I’m on my way to Milwaukee, and I noticed this stick, about the size of a pencil, hanging on twelve inches of string from the ceiling. Willie goes, “That’s our magic stick.” I said, “Really?” And he said, “Yeah. It tells us what we need to know. If it’s wet, it means the bus is underwater. If it’s on the roof, that means the bus is upside-down.” I said, “Okay.”

It was a pretty wild ride. The term back then was roaring. Bee Spears [Willie’s bass player] or somebody would say, “Let’s roar, Hubbard!” and that’s what we’d do. So we roared all the way to Milwaukee, they played the beer fest, then we started roaring back home. And it got so crazy that when we hit Chicago, I saw that Jerry Jeff was playing a club there. So I told Willie, “Let me out here. I need to go hang with Jerry Jeff. You guys are killing me.”

Steve Earle

is a San Antonio–born singer-songwriter, author, actor, and political activist.

Willie Nelson moving back to Texas saved my life. I used to get my ass kicked pretty much every day in high school. I had long hair and cowboy boots. I got my boots stolen a couple times because the rednecks didn’t think I was supposed to have them. I got my hair cut with a pocketknife. I was a target for people like that. But when Willie moved back, suddenly I was standing in a cow pasture with guys who used to kick my ass, listening to the same band.

I knew who Willie was before a lot of them did because I went to Holmes High School, which is about eleven miles from John T. Floore’s Country Store [where Willie played regularly during the sixties and seventies]. And my high school biology teacher was George Chambers, who had one of the best country bands in San Antonio. He never got a major label deal, but whenever he went to Nashville, he would stay with Willie at his place in Ridgetop. And Bee Spears was from Helotes and went to Marshall High School, which was about five miles from Holmes. I knew Bee. I knew all those guys. So I knew about Willie.

But Shotgun Willie was when I focused in and realized I needed to have that stacked on my record changer with ZZ Top’s Tres Hombres and King Crimson’s In the Court of the Crimson King. And I was at the Dripping Springs Reunion. I was at the first Fourth of July Picnic. I hitchhiked to the Abbott Homecoming show.

I saw him play a dance hall in Pasadena when I was eighteen, in 1973. This was relatively early in the whole thing with hippies and rednecks being in the same place to see Willie. And Pasadena was rough. The local Ku Klux Klan clubhouse—and it was a clubhouse with a f—ing sign on it—was in Pasadena. The Klan was famous in those days because they blew up [Houston community radio station] KPFT’s transmitter twice. I think they’d decided KPFT were communists or pro-Jew or something.

The rednecks got to the show first, and they sort of hung back for a while. Then the hippies came in and sat on the floor to listen. When the music started, the rednecks start dancing, and they’re kicking those kids sitting in front. Willie stopped the show in the middle of a song and said, “There’s room enough for some to dance and some to sit.” That chilled it out.

And that’s Willie. Whatever else is going on, he’s serene. He knows he’s Willie Nelson, and he’s pretty comfortable with that. That gets a lot of s— out of the way.

Chet Flippo

“Matthew, Mark, Luke, and Willie,” excerpted from the archives: September 1975

Country music, if you believe all the critics who have misread a recent movie called Nashville, is made up entirely of smarmy concoctions of drink, divorce, Fundamentalism, and other cheap, unchic subjects. Country musicians, if one subscribes to Nashville’s credo, are perhaps one generation removed from cave dwellers. Their primitive musical instincts reveal themselves in cretinous tunes that parallel their wretched lives lived out in an alcoholic daze.

Country music sometimes may reflect such a life—but it is much, much more in the hands of its few truly gifted songwriters. The best of them is a man named Willie Nelson who has recently recorded an album so remarkable that it calls for a redefinition of the term “country music.” The difference between Nelson’s Red Headed Stranger and any other current C&W album is astounding. What Nelson has done is simply unclassifiable; it is the only record I have ever heard that strikes me as otherworldly. Red Headed Stranger conjures up such strange emotions and works on so many levels that listening to it becomes totally obsessing. The world that Nelson has created is so seductive that you want to linger there indefinitely.

Chet Flippo was the first stringer for Rolling Stone to be stationed in Austin.

Bobby Earl Smith

played bass in Austin’s original progressive country band, Freda and the Firedogs, and is a former criminal defense attorney in Austin.

Joe Gracey [program director at Austin’s KOKE-FM] and I went by [sound engineer] Phil York’s studio in Garland. As we pull up, Bee Spears walks out looking all beat-up. He’d been living in there with Willie for days. He said, “I’m going back to Austin.” We walk in, and Phil says we’ve got to hear what Willie cut. Now usually, when you’ve just wrapped something, you’re sick of it, you don’t want to hear it for a while. So we said sure. He said, “Let me back it up. You have to hear it from the beginning. It tells a story.” When it got to “Blue Eyes Crying in the Rain,” I almost fell on the floor. I thought, “God, that’s the prettiest thing I’ve ever heard.”

Gracey started playing the s— out of it on KOKE, especially “Blue Eyes.” And that song started getting played all over the country. Here comes the legitimacy that’s always been just out of reach. Willie’s got a hit. A monster hit. Everybody loved “Blue Eyes”—in farming communities, everywhere. Suddenly it didn’t matter who had long hair.

Mickey Raphael

has been Willie’s harmonica player since 1973.

Red Headed Stranger was recorded live. Willie said, “I wrote this album, this concept record.” And we hadn’t heard it till we went in there and he started playing it for us. I mean, the tape machine’s rolling the whole time. That’s really why it’s so sparse, because we’re just kind of listening and learning the songs. I don’t think we played them but a couple of times, and we did it in two days. We were all just mesmerized by what he was doing.**

** Excerpted from “Willie’s God! Willie’s God! We Love Willie!,” by Michael Hall (Texas Monthly, May 2008).

Rodney Crowell

is a Houston-born singer-songwriter who lives in Nashville.

I remember being at a guitar pull at [UT football coach] Darrell Royal’s house not long after Willie’s Fourth of July Picnic in 1973. I was just a shy 22-year-old with a few songs that were pretty good, and I think Mickey Raphael goaded Coach Royal into asking me to play something. So I played “Till I Gain Control Again.” Willie didn’t really indicate what he thought at the time, but a couple years later, I heard he’d started playing it in his live show. I felt like I was knighted as a songwriter.

Flash forward to early 1978. Willie was recording at Studio in the Country, in Bogalusa, Louisiana, and I was living in Los Angeles. One day, a plane ticket came in the mail, with a note that read, “Come on down to Bogalusa and help us record ‘Till I Gain Control Again,’ Willie.”

So I flew down to New Orleans and got picked up and taken to the studio. It’s pretty far out there, down at the end of a long gravel road with open fields on either side. And as we drive up, I see this Camaro out in the middle of this field, just cutting doughnuts and spinning around as fast as it could. I said, “God, what’s going on out there?” The driver said, “Guess who’s driving that car?” I had no idea. “Bee Spears, maybe?” He said, “No, that’s Stevie Wonder.” And I said, “Oh, this is gonna be fun.”

It wasn’t long before we recorded my song. Willie sang it so beautifully, and he played this breathtaking guitar solo. I added some harmony and that was it. It was like, wow . . . I don’t know what could be any better than that.

I took a reel-to-reel tape of it back to L.A. and played it for all my friends. I told them, “This is going to be Willie’s next big thing.” But time went by, and it wasn’t released. His next record was Willie and Family Live, and he did a version of “Till I Gain Control Again” on that. Frankly, it wasn’t nearly as nuanced as what we did in the studio, but that version never did come out. And I’ve lost my reel-to-reel copy.

But that’s just the way Willie rolls. I’ve never known anyone who was so in-the-moment.

[Editors’ note: The album Willie recorded in Bogalusa was, in fact, released in 1991 as The Hungry Years by Sony Music Special Projects. Texas Monthly sent a copy of that version of “Till I Gain Control Again” to a very grateful Crowell.]

Jessi Colter

is a singer and Waylon Jennings’s widow. She had a number one country hit in 1975 with “I’m Not Lisa.”

I’ve got so many Willie and Waylon memories that it’s hard to weave them into one story. Willie came over for a songwriting session at Southern Comfort, our old home in Brentwood, Tennessee, one day in 1978. Our basement had just flooded, and a geologist had determined the house had been built on top of a spring, so a contractor was jackhammering the patio to dig twelve feet down and reroute the water. Willie just sat in the living room, unfazed and smiling, like he didn’t even notice the demolition crew blasting away. And then he and Waylon wrote “I Can Get Off on You.”

In October 1982, Waylon and I had taken a house in Malibu for a month. He went out for a walk on the beach and about an hour later returned with Willie. There was no mention of how he just happened to find Willie out there, but they came in and Waylon said Willie was staying for lunch. Waylon left the room for a few minutes and came back, didn’t see Willie anywhere, and asked, “Where’d he go?” I said, “He is sitting on the kitchen floor coloring with [our son] Shooter.”

There were so many great moments like that. At the sobriety party that Johnny and June Carter Cash gave Waylon when he got off drugs, Willie had cut off his pigtails and sent them to Waylon for his sobriety gift.

George Strait

is George Strait.

I played golf with Willie a couple times. The first time was at the tournament he hosted each year with Coach Royal, the Darrell and Willie Invitational. It was at Barton Creek Country Club and it was me, Coach Royal, Willie, and [legendary pro golfer] Chi Chi Rodriguez in a foursome. Willie went first and hit a bad drive, so he immediately took a mulligan—which was funny, because there were no mulligans. But hey, it was his tournament. So, we got to the green and Willie had a really long putt for maybe a six. He asked Chi Chi to give him a read. Chi Chi looked at it from both sides then walked over, picked the ball up, tossed it to Willie, and said, “It’s too hard. You can’t make it.”

Ray Benson

is the founder and leader of Austin western swing band Asleep at the Wheel.

Once, we were out playing golf, and I said, “Man, you oughta go take a lesson. Your golf swing sucks.” And Willie said, “If there’s a right way to do things, I’ll try the wrong way first. Every time I did it the right way”—like in Nashville—“nothing happened. When I finally did what I thought was the right way”—and here he was talking about “Blue Eyes Crying in the Rain,” which everyone else thought was the wrong way—“everything fell into place.” So, you know, just trust yourself and follow your instincts.**

** Excerpted from “Willie’s God! Willie’s God! We Love Willie!”

Bee Spears

grew up in Helotes and was Willie’s bass player from 1968 until Spears’s death in 2011.

We play golf anytime we have a day off. We plan our bus routes around the golf courses. The only reason we’re playing music now is to support our damn golf habit.**

** Excerpted from “Willie’s God! Willie’s God! We Love Willie!”

John Mellencamp

is a rock star and a member of the Farm Aid board of directors.

In 1985, before the first Farm Aid in Champaign, Illinois, Willie and I rode together in his tour bus to the press conference a couple of days before the show. There were hundreds of reporters there, and we spent a long time talking and answering questions. I felt like the press conference was over, so I went back to the bus; Willie stayed and talked and signed autographs. I waited for about an hour. When he finally showed up at the bus, I said, “Nelson, what have you been doing?” He told me, “Something you should think about doing: paying attention to the public and your fans.” It was a teachable moment.

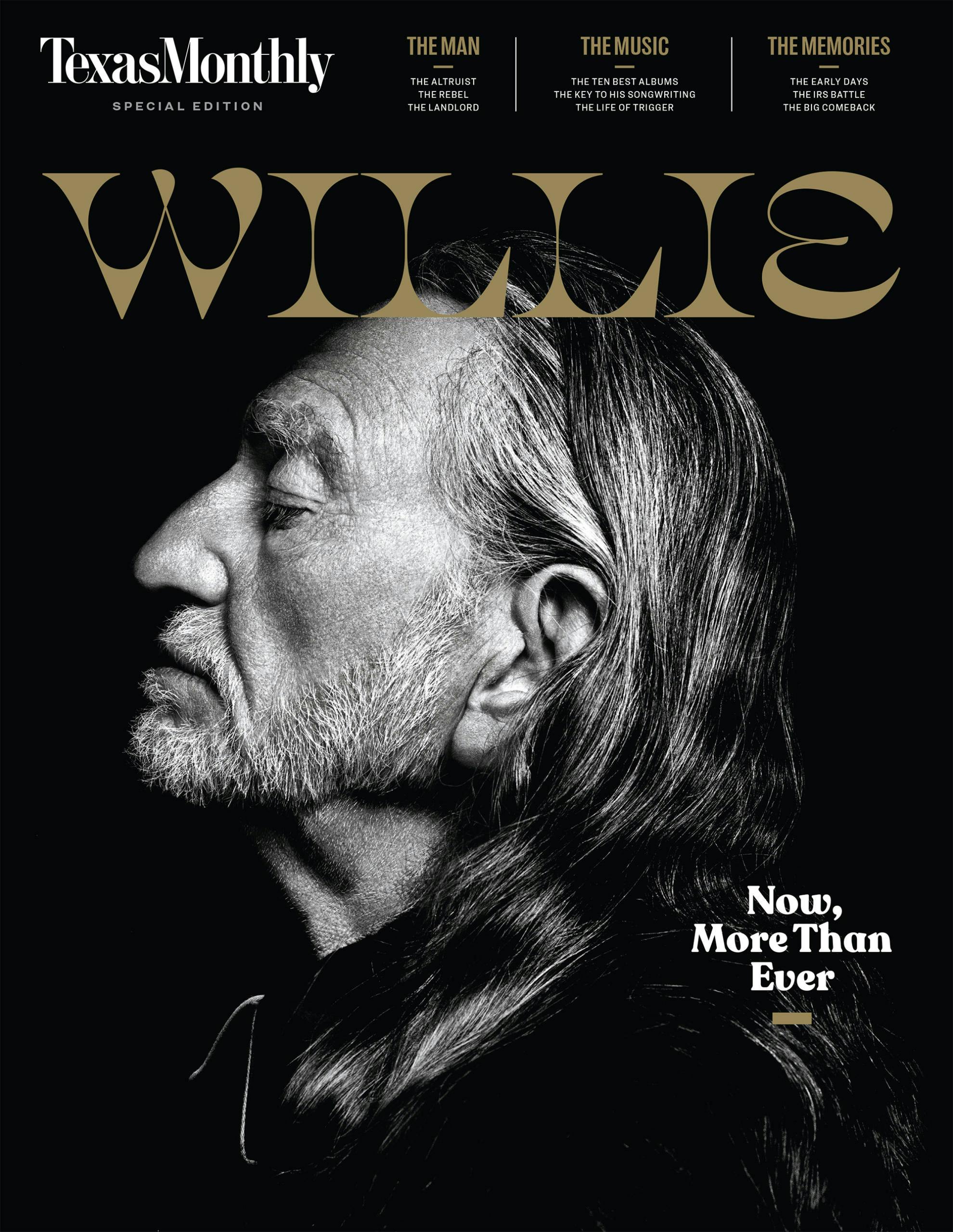

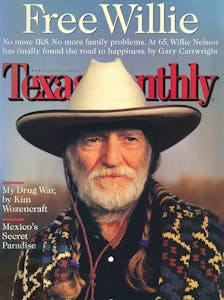

Michael O’Brien

is an Austin photojournalist who shot the photograph of Willie that appeared on the cover of the May 1991 issue of Texas Monthly.

I got to know Willie when he was shooting Red Headed Stranger at his ranch in Luck in 1986. Life magazine sent a writer, Cheryl McCall, and me down there to document him making this movie, and we stayed for thirty days. Every morning, Cheryl and I’d go pick him up at his ranch house. It had a wraparound wooden porch, and he’d always be sleeping out there, in a ratty old sleeping bag, in his running shorts. We’d honk, Willie would rub the sleep from his eyes, invite us in for a cup of coffee, and then ride with us down to the set. He was always incredibly generous with us.

A couple years later I needed to shoot him for National Geographic, and that’s the image that was used for the Texas Monthly cover. When I asked if I could take his picture, he said, “Well, I don’t think we’re doing anything tomorrow afternoon.” I’d told him I wanted to do it at sunset. And he said, “Oh, I love watching the sun go down.”

I set up on a little plateau right below the ranch house. I’m always nervous before shooting someone, and when he showed up—right on time—I told him, “I don’t want to screw this up.” But he was completely relaxed. He wanted to know what I’d done since Red Headed Stranger. Then we started talking about one of his roadies, Ben Dorcy, who I’d met on the movie set, and what a great storyteller Dorcy was. Willie asked if Dorcy’d told me about working for Johnny Cash. He said that once, when Johnny left his hotel room, Dorcy took all the furniture out of Johnny’s room and brought in furniture from a completely different room to freak Johnny out when he came back. For a good while, we just talked and laughed like that.

And then I shot his portrait. He was already a mythical American figure, so I needed to make a portrait that had the intensity and stature of the man. I wanted to keep the focus on his face. It’s almost like a landscape, with mountains, canyons, valley, shadows, and darkness. There are a lot of miles on that face. And really, nothing more was needed than having Willie completely focused into the lens.

Sally Wittliff

is the widow of Austin writer Bill Wittliff, who wrote the screenplays for the Willie movies Honeysuckle Rose, Barbarosa, and Red Headed Stranger.

After the IRS had come in and taken over Willie’s studio, put locks on the doors and all that, Bill called Willie and said, “I am so sorry.” And Willie said, “Oh, I don’t care about any of the stuff in there.” Bill said, “Well, there’s that Indian headdress that the Hopi tribe gave you.” And Willie said, “That’s in there?” And Bill said, “Yeah, it’s over in the back corner.” Then Bill said, “And that great guitar that so-and-so gave you?” Willie said, “That’s in there?” And Bill said, “Yeah. It’s over on the counter.” And then Bill went through about five or six other things, and got the same reaction from Willie each time: “That’s in there?”

Next day, we open the paper and there’s been a break-in at the studio. And the things that were taken were the Indian headdress, the guitar, and all the things Bill had mentioned to Willie.

Kimmie Rhodes

is a singer-songwriter who lives near Pedernales Studio in Briarcliff.

After Willie bought the country club outside Austin [in 1979] that became Willie World, a bunch of us—Willie’s friends and folks who worked for him—ended up living out there. My husband, Joe Gracey, and I built a house just down the hill from the studio that Willie put in the old golf course clubhouse. David Zettner [Willie World’s resident visual artist and utility string player] had a house on the river. And there were also some condos near the studio, with people in them like a guy we called Computer Bob, who taught us all how to turn on computers, and another named Bucky Meadows. His job was to look after the studio, but when Willie was in town, he liked to pick with Bucky and Zettner. Bucky played guitar like Charlie Christian. He was brilliant. Willie always said Bucky was “between hits.”

Willie had a condo, and he had Zettner paint a big oak tree on a wall that stretched out onto the ceiling. Willie would pitch a tent in there to sleep under the tree.

It was just so much fun, especially when Willie’d drag us into whatever he was up to. Like the Cowboy Channel [a satellite-television channel that Willie started in 1990, which broadcast fifties- and sixties-era country music shows, along with old Hollywood westerns and original programming produced in Willie’s studio]. It was all very organic. We had all this wood that had been brought down from Willie’s old barn in Abbott, and one day we nailed a bunch of it up on the wall in the living room of one of the condos to be a backdrop for broadcasts.

So one night I had a gig at the Broken Spoke [the Austin honky-tonk]. It was my birthday, which happens also to be the anniversary of the fall of the Alamo, so Zettner had painted this giant Alamo mural to put onstage during my show. I finished the gig and got everybody paid at around one a.m., at which point we—me, Gracey, Zettner, and Bucky, who were all in my band—got word that Willie was up to something back at the condos.

We got there around three a.m., and Willie and Computer Bob had started up the satellite truck, and Willie was hosting a late-night call-in TV show live from the condo with the barn wood. He had a phone in there, and people were calling in from all over to request songs. Only, it was just a regular, landline phone, so you couldn’t hear the callers. You just heard Willie talk to them, and then he’d play their requests.

We show up, and Willie says, “We’re going to take a break, and we’ll be right back.” But, of course, there were no commercials, so the screen just went to black while we got that Alamo mural and set it up. Then the show came back on, with us all sitting there around the phone, taking requests and playing songs. And we went until six-thirty or seven in the morning. I was literally falling asleep on the air.

Finally, this lady calls in, and her name is Irene. Willie talks to her for a little while, and then he turns to me and says, “Kimmie, do you have anything you’d like to say to Irene?” And I said, “Yes . . . good night, Irene!” So Willie hung up the phone and we all sang [the old Lead Belly standard] “Goodnight, Irene,” unplugged the satellite, and went to bed.

Paul Franklin

is a steel guitar player and one of Nashville’s premier session musicians. He has appeared on five Willie albums.

I’d just ended a tour with Dire Straits in the fall of 1992 when [producer] Don Was asked me to play on a Willie album, which ended up being Across the Borderline. Don was a new producer for Willie, and he hired this unique band and brought in all these iconic artists, from Paul Simon to Bob Dylan to Bonnie Raitt. But Willie was the glue. They all had this personal connection to him, had all been influenced, inspired by him. As a session player, I’m a fly on the wall, and all these heavyweights were telling Willie, “Hey, I had this record of yours,” and “Wow, Willie, you did this.”

We recorded the album in New York, and all of us stayed at this five-star hotel. It was an awesome place. Each morning, we’d all get together downstairs for a great breakfast. And I remember asking Reggie Young, who played guitar on the record, “Is Willie going to come down and eat? You think he’ll come hang?” And Reggie said, “He’s sleeping in a sleeping bag on his bus.”

Lyle Lovett

is a singer-songwriter from Klein who has been nominated for seventeen Grammys and won four.

Willie recorded two of my songs for Across the Borderline—“Farther Down the Line” and “If I Were the Man You Wanted,” which was just a tremendous honor. And when the record came out, he did a showcase at the Roxy that was broadcast live on Westwood One, and they invited me to come in and sing harmony on those songs. At the end of the show, we were all out onstage doing “Still Is Still Moving to Me,” which was also on that record. That song—even just its title—is such a perfect encapsulation of Willie Nelson. I mean, “Still Is Still Moving to Me?” You bet it is!

So we’re singing it, and I look at the monitor and see that it’s flashing ten more minutes. And I know for sure this is the last song. But they’re telling Willie there’s ten more minutes. He gives me a glance, and I think, “Am I supposed to do something?” We both look at the monitor again, and then he looks back over at me, and I’m thinking, “No, no way.” We’re getting close to the end of the song. He looks at me again and I’m thinking, “Don’t, do not, please.”

When the song’s finished, Willie walks over, pulls Trigger over his head, puts it on me, and says, “Play something.” And my very first thought was, “What in the world can I possibly play without a capo?” So I started into “The Church Song.” It’s in the key of G, and the changes are insignificant enough that the band just played the one chord all the way through. It was truly a moment of terror, me standing there, onstage, with Trigger. But I can still picture Willie pulling that red, white, and blue guitar strap over his head and putting it over mine. I felt like somebody was hanging a medal on me.

Kinky Friedman

is a singer-songwriter and author who lives in Kerrville.

I had this girlfriend who was about six feet tall, and I brought her on [Willie’s] bus. We stood back-to-back to see who was taller, me or [her], and I said her ass is higher than mine. Willie said, “My ass is higher than both your asses.”**

** Excerpted from “Willie’s God! Willie’s God! We Love Willie!”

Dan Winters

is a photojournalist based in Wimberley who shot Willie for the April 1998 cover of Texas Monthly.

That was the first time I ever shot Willie. It was in Bakersfield, California, out in front of Buck Owens’s dance hall there, the Crystal Palace. It’s kind of a destination for country music fans, and Willie was playing that night with Leon Russell. I remember while we were setting up, my producer told me that Buck Owens once said that Willie didn’t get famous until he got ugly, which is pretty funny.

There was a Walmart about a thousand yards away, with a big, empty field in between that would give a good, clean background, so we set up there. I’d seen Willie earlier, standing outside the bus in his civvies: flip-flops and a T-shirt. But then he showed up with that sweater and hat on, totally set for a photo shoot. He was amenable to everything I asked, but I tried not to control things too much. I just wanted to get him within his own thoughts and give the viewer something to connect to, some pensive moment. Thirty minutes later, the shoot was over.

Afterward, Mickey Raphael said, “Willie and Leon are on the bus, why don’t you go in there?” So I go in and they’re at this little table. I sit down and start debriefing with Willie about the shoot, and I look over and see Leon rolling a joint. And then he lights it. Well, I’d gotten stoned way back in the day, but I didn’t smoke weed at all at this point. But I thought, I’m at Willie’s table, and this is Willie’s weed; I’m not turning this down. So Leon hands it to me, I take a hit and hand it to Willie, who takes a hit and hands it back to Leon, and then it’s back to me and back around, and finally I say, “That’s three hits, I’m good.” And they go on talking, reminiscing some, getting ready for the show that night, discussing somebody I didn’t know, maybe somebody in the band or something . . . and pretty soon my head is spinning, and I’ve got to leave. I was a zombie. It was the strongest weed I’ve ever experienced—and the last time I ever smoked.

Paul English

was Willie’s drummer from 1966 until his death in 2020.

Used to be the biggest problem [Willie] had was drinking. Back when he drank, the first thing he’d want to do was drive a car. I would chase him down and try to get the keys away from him. He’d get dishes and throw ’em over the balcony, punch holes in walls, tear up rooms. He don’t drink anymore. He changed over to weed slowly. When he smokes weed, you can’t even tell it. He says, “I don’t smoke weed to get high. I smoke weed to get normal.”**

** Excerpted from “Willie’s God! Willie’s God! We Love Willie!”

Evelyn Shriver

was Willie’s publicist from 1991 to 1998 and serves on the board of Farm Aid.

I think that the relationship between him and [his sister] Bobbie is the real constant in his life. I’ve spent a lot of time with them, and they both read a lot, and they’re both very curious about different spiritual things and philosophies. I think that on long road trips they’ve had some really interesting conversations that have given them both that kind of serene touchstone that most people don’t have.**

** Excerpted from “Willie’s God! Willie’s God! We Love Willie!”

Jimmy Carter

was the thirty-ninth President of the United States.

When I had my most difficult times [during my presidency], I would go in my private study and tie flies for fly-fishing and listen to Willie’s music.**

** Excerpted from “Willie’s God! Willie’s God! We Love Willie!”

Billy Joe Shaver

is a singer-songwriter from Corsicana. His son Eddy played lead guitar in his band from his early teens until his death at 38.

My son Eddy died of a heroin overdose in 2000. I got to the hospital and said, “I’m here to see my boy,” and they said, “He’s dying.” Sure enough, he was. I managed to get his boots on him, but he died downstairs there. They took him upstairs and brought him back to life—and then he died again. He always had a saying that he didn’t like to rehearse. But I guess he did this time, because he died twice.

We had a show scheduled to play at Poodie’s that night, and none of my band showed up. They’d been with Eddy when he overdosed, and I think they thought I’d kill ’em all. And I probably would have. But Willie came with his band and took over. And you know how he is—so damn cool and calm, his whole spit-in-the-devil’s-eye thing—that’s how he did the show. I’d get up every once in a while and sing what I could, but it was hard. I’m not a very emotional guy; it’s hard for me to cry. But I did have one of those that night, way out back, off by myself.

And of course, Willie’s son Billy had died a few years before. I’d been real close with Billy—both of us were borderline crazy—and Willie knew that. But he never gave me any advice about Eddy. He just showed up for me. And then he paid for the funeral.

Peter Cooper

is a Nashville-based singer-songwriter and music journalist who works for the Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum.

I was writing for the Nashville Tennessean in 2002, when Willie’s The Great Divide album came out. The album was ultra-glossy—Rolling Stone’s review aptly noted the abundance of “adult-contemporary production goop”—and it’s probably my least favorite Willie album. But I was quick to take the rare opportunity to interview him on his bus just prior to release. I knew Willie eschewed negativity in any form, so I hemmed and hawed when I asked about The Great Divide’s goopy nature.

Finally, I said, “Your ascent to superstardom came in the seventies with Red Headed Stranger. Do you think someone who loves the spare, sparse sound of that album would like The Great Divide?”

His eyes flashed, and he stared through me for a half second before saying, “No, I don’t.” Then he half-chuckled and said, “But my fans know that when I put out an album they don’t like, I’ll have another one out in fifteen minutes that they might really enjoy.”

Lucinda Williams

is a singer-songwriter who has been nominated for fifteen Grammy awards and won three.

In 2004 Willie and I did a song together that I wrote, “Over Time,” for his album It Always Will Be. We were both signed to Lost Highway, which may be why that happened, but when it first came up, I was completely floored, humbled, honored—all of the above. I did think it was a perfect song for him, kind of country-slash-jazz, like the stuff he does so well. It sounds like something Ray Price might have recorded.

They had already been working for a while when I got to the studio. And I remember being worried to no end, because everything had been cut except for my vocal—and the song wasn’t in the right key. It was too high. I thought, “Damn it, I’m going to have to do this somehow.” But Willie was there. I think he said, “Oh, honey, it’s going to be fine,” and offered me some whiskey. It still wasn’t the most comfortable thing. I had to stretch my voice to its upper reaches; it doesn’t have that edgy thing it usually does. But it came out kind of airy and soft, so the song sounds sweet.

A few months later we did it live at the Wiltern Theater in Los Angeles [as part of a concert that was later released as Outlaws and Angels]. I asked him before the show, “Do you mind if we do it in a little lower key?” And he said, “That’s fine, whatever key you want to do it in,” re-tuned his guitar, and that was it. So when you hear that live version, it sounds more like me because Willie let me sing it my way. And his sweet nature shines through. I listened to it again recently and it just made me cry.

Miranda Lambert

is a country star from Lindale and a seven-time winner of the CMA’s female vocalist of the year award.

I performed at the Kennedy Center Honors Merle Haggard tribute in 2010, and before I went onstage, I ran into Willie and he asked, “How are ya?” It took everything within me not to jump up and down and say, “This is the best moment of my life!” But I just smiled and said, “Right this minute I’m doing mighty fine.” Something about Willie makes you feel calm and okay just being you.

Toby Keith

is a country star who has had twenty number one singles.

I was at an after-party following an award show. It was at the Palm restaurant in Nashville. My longtime guitar player, Joey Floyd, was with me, and he’d played Willie’s son in Honeysuckle Rose. We saw Willie as we walked in, and Joey said, “Hey, Willie.” I’d met him a few times with Joey, so I said hey, too. And then I said, “I’ve got a song I wrote, a western-themed tune. Would you consider singing on it?” He said, “Send it to me so I can hear it.” I said, “Okay, I will.” A few minutes later he came back and said, “What is the name of the song, so I’ll know when I get it.” I said, “It’s ‘Whiskey for My Men, and Beer for My Horses.’ ” And Willie said, “Hell, I don’t need to hear that. I’m in.”

Later, after “Beer for My Horses” had gone to number one, I ran into Willie in New York City. I said, “Our song did real good, didn’t it?” He said, “It did?” I said, “Yep. Six weeks at number one.”

“Well, damn,” he said. “I guess I should add it to my show.”

Joe Nick Patoski

“Entertainer of the Century,” adapted from the archives: December 1999

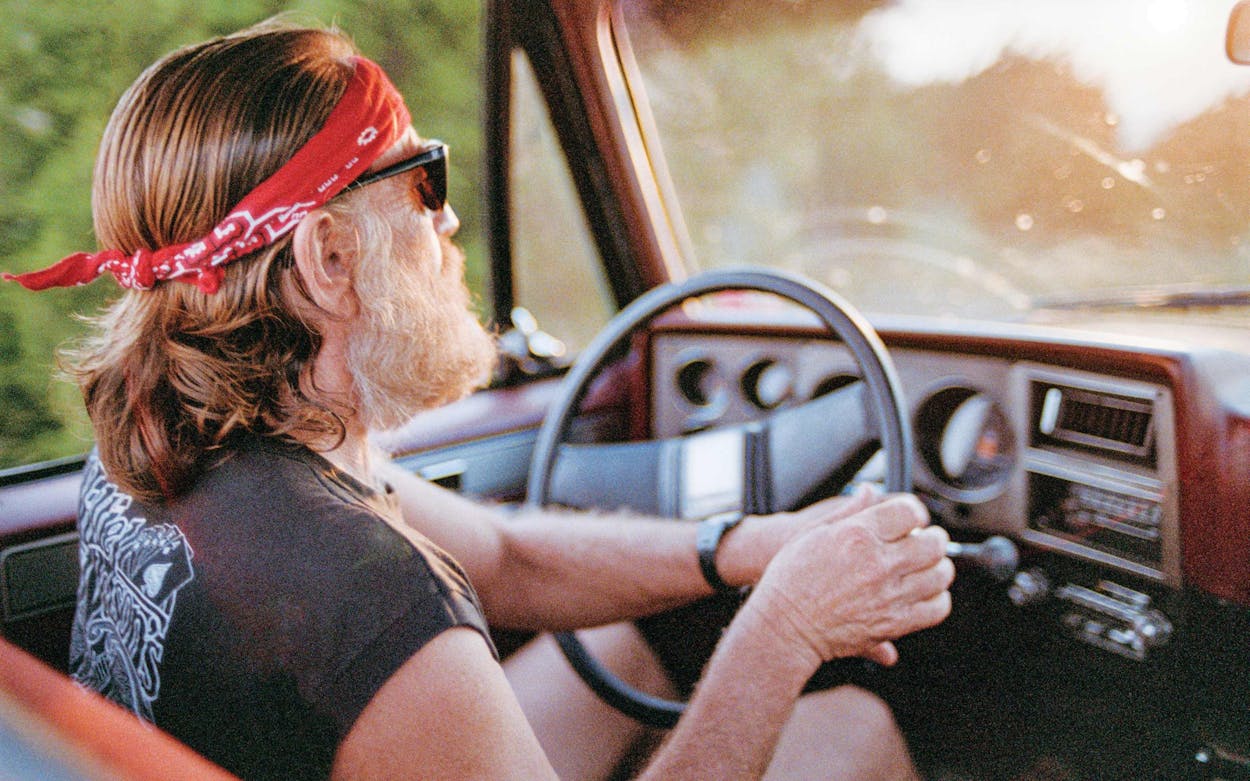

When you ride shotgun with Willie Nelson around the back roads of Willie World, the self-contained universe he created for himself and his extended family in the Hill Country west of Austin, you realize what it is that makes him such an icon. It’s his Willie-ness. It hits you while watching the old guy in black with the scraggly beard and the puppy-dog eyes undo a braid on his pigtail. He doesn’t fit the stereotype of a 66-year-old veteran of a profession that eats its young. The goofy grin he flashes conveys the vibe that he really and truly likes what he’s doing.

As he tools around in his pickup truck in a state of herbal bliss, he’s locked in a zone of his own and right in sync with the master plan hatched at age eight. “I started out watching Gene Autry and Roy Rogers every Saturday on the movie screen in Hillsboro [ten miles north of Abbott, his hometown],” he says in his relaxed drawl. “I knew what I wanted to do: I wanted to be a singing cowboy, ride my horse, play my guitar, shoot my gun. So here we are.”

Four dogs with wagging tails are waiting for him on the porch as he parks the pickup next to the World Headquarters in Luck, an old-timey saloon with a satellite dish on the roof, a fully stocked bar, and a movie screen with church pews for seating. The walls are adorned with Willie posters, Willie album covers, and snapshots of Willie with friends like Richard Pryor and Johnny Bush. There’s even a photo of Willie with his cowboy hero Gene Autry.

His buddies, a casual, semigrizzled bunch partial to gimme caps, jeans, and running shoes, gather around the J-shaped bar while their boss eats his eggs and beef bacon. And when he’s done, he vanishes out the side door by the back of the bar, just like Autry used to do in the movies. “Well, here I go,” Willie says. “It’s time for my favorite thing to do: gotta go get my picture taken.”

He tries to make it sound like a burden, but his complaint rings hollow. He walks a hundred yards to the Opera House, where a photographer and his assistants are waiting. He sits on a stool in a makeshift studio, quiet, patient, occasionally flashing that goofy grin, doing what needs to be done, giving the photographer all he wants. The photographer looks like he’s having the time of his life, and so does Willie, and so does everybody else milling around Luck. It’s the Willie Way.

Wimberley-based writer Joe Nick Patoski is the author of Willie Nelson: An Epic Life.

Annie Nelson

has been married to Willie since 1991.

When Willie and the Dalai Lama get together, they’re like a couple of eight-year-olds. They’re laughing and talking and they crack each other up, and you know it’s a mutual exchange. I’m not saying he’s on the level of His Holiness the Dalai Lama, but there’s a recognition in each of them when they’re together. They can relate.

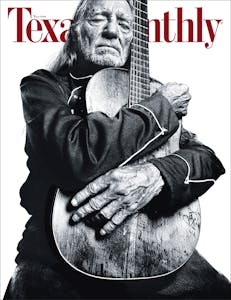

Platon

is a photographer who was born in Greece, raised in England, and lives in New York. He shot Willie for the May 2008 cover of Texas Monthly.

There’s an album Willie made called Spirit. When I first arrived in New York in 1998 with nothing but a suitcase and a camera bag, starting my life over in America at thirty, that CD got me through the first few weeks. I played it to death. And the reason it was so meaningful is because the songs are rooted in an American tradition of storytelling, but the ideas—dealing with love lost, missing someone—are universal. It’s a bit lonely when you’re on your own, no connections, not sure if you’re going to get an agent, if you’re going to get a chance to show the world what you’ve got. But what do you do when you’re lonely? You fall back on art to inspire you to move forward. And Willie supplied that perfectly. His stories about longing for someone reminded me of my family. I did not know if it would work out, and in those situations, you’ve got nothing but hope. That’s the currency. And that’s what’s embedded in that album.

For this shoot, we rode together to his ranch. I remember asking when we arrived, “Willie, why is your town called Luck?” And he said, “Sometimes, you’re in luck. Sometimes, you’re out of luck.” That’s his genius; he’s joking around, but if you think about what he just said, he’s talking about life. He called his town Luck because we all go through this. We all have our little winning streaks and losing streaks. It’s actually very philosophical.

I did think, though, that I may be reading into things because America’s not my natural culture. And Luck was about as American as anything I’d ever experienced. I mean, I’m an Englishman; I’d never seen anything like this. He had built a cowboy town. There’s a saloon. There’s a jail. It’s all there, covered in dust, horses everywhere. It was like stepping into a movie. It was like being in High Noon.

That’s where we did the pictures. I set up my white background in this building on High Street, his saloon, and started waiting. And it took him a while. His bus was parked on the outskirts of the block, and he was in there with some friends. Eventually he sort of staggers out with his guitar case in this cloud of smoke. And he seemed pretty stoned.

He comes in and sits on this apple box that everyone sits on in my pictures. Putin has sat on it, all our living American presidents have sat on it, Gadhafi has sat on it. And now, Willie Nelson sits on it. But it’s got no back. It’s just a box, right? He was a little unsure of his balance, and he almost fell off. So I say, “We need something for him to hold on to.” Without saying anything, he gets up, opens his guitar case, and takes out his guitar. And it’s all a bit wobbly. He gets back on the apple box and holds onto his guitar to keep his balance. And as he’s clinging to his guitar, he actually nods off and has a snooze.

And that’s the picture: this man with his arms around his treasured guitar. And it became famous in America because people felt it’s the quintessential American artist embracing his art.

Buddy Cannon

has produced thirteen of Willie’s last fourteen albums and co-written dozens of songs with him.

I was hanging out on Willie’s bus before one of his New Year’s Eve shows in Austin when someone brought on a lady who Willie and Annie both got up to greet and hug, so I gave her my seat across the table from Willie and sat on the couch. She started talking about somebody who had recently passed—I presume her husband—and Willie was listening intently. She was still very sad and troubled. I remember her saying, “I just don’t know how I’m gonna ever get over this.” And Willie said, “It’s not something you get over, but it’s something you get through.”

I didn’t write that line down, but it stayed with me, and I thought about it every day for two years. Finally, I sat down and wrote some lyrics and sent them to him in a text message. And he added some stuff and texted it back. That’s how we write. And I love writing with Willie. He’s not chasing radio; he can sing whatever he wants. There’s a great sense of freedom in that. It deepens my thinking.

The song ended up being “Something You Get Through,” and it’s been viewed 37 million times on Facebook. And almost three million more on YouTube. It’s kind of crazy. But I guess there are people who need it, who have loss. It’s very gratifying to think that this little, eight-line song is giving people comfort.

We recorded it the same way we record most all of them. I get the basic tracks down in Nashville and bring them to his studio in Pedernales. Willie always walks in, says “Hi” to whoever happens to be around, then walks over to his spot in the corner just outside the control room door. There’s a chair there for him—it’s just a folding chair—by a window that he can look out of onto a lake, off in the distance.

Sometimes he’ll sit there three or four hours before he gets up. He’ll go song by song, giving each one three or four vocal passes, and then pick up his guitar and play on a couple passes. Sometimes he’ll pick and sing at the same time, you don’t ever know. And my main job is to read him, make sure he doesn’t get bored, keep things moving—and to just be ready to capture whatever he does.

These interviews have been edited for clarity and length.

This article originally appeared in the Willie Nelson special issue of Texas Monthly with the headline “That’s Just the Way Willie Rolls.” Subscribe today.

- More About:

- Music

- Willie Nelson