There’s a scene near the end of The 24th, Kevin Willmott’s new film on the Houston riot of 1917, that plays like a fever dream. The camera cuts between locations as an Army officer reports, through voice-over, “the men identified as the ringleaders of the mutiny …” Then we’re met with a pregnant pause. Marie Downing (Aja Naomi King) is the sweetheart of one of those ringleaders. She sways back and forth on a swing set, with a smile on her face. Cicadas, birds, and crickets sing; dawn glistens through trees as an ominous shot of the swingset’s rope foreshadows what’s to come. The handsome face of Downing’s beau, Corporal William Boston (Trai Byers), fills the screen. They probably would’ve married if he hadn’t been martyred with his brothers of the 24th Infantry, following a mutiny that they undertook on August 23, 1917.

The officer finishes his sentence: “… were hung this morning shortly after five-thirty. May God have mercy on their souls.”

The screen fades to black and we hear a clink. A thud. A jolt. A rope tightening and swaying back and forth.

The 24th, a fictionalized account of the Houston riot of 1917, is a deeply resonant and perceptive window into American humanity. Directed by Willmott, whose screenwriting credits include Da 5 Bloods and BlacKkKlansman, the film was originally set to premiere at South by Southwest before the pandemic led to the festival’s cancellation; the movie is now streaming on Amazon Prime. The 24th sheds light on an important and long-overlooked moment in Texas history. But, at times, it also feels threadbare. The film is safe, a little heavy-handed, and not nearly as dangerous or radical as the men who inspired it.

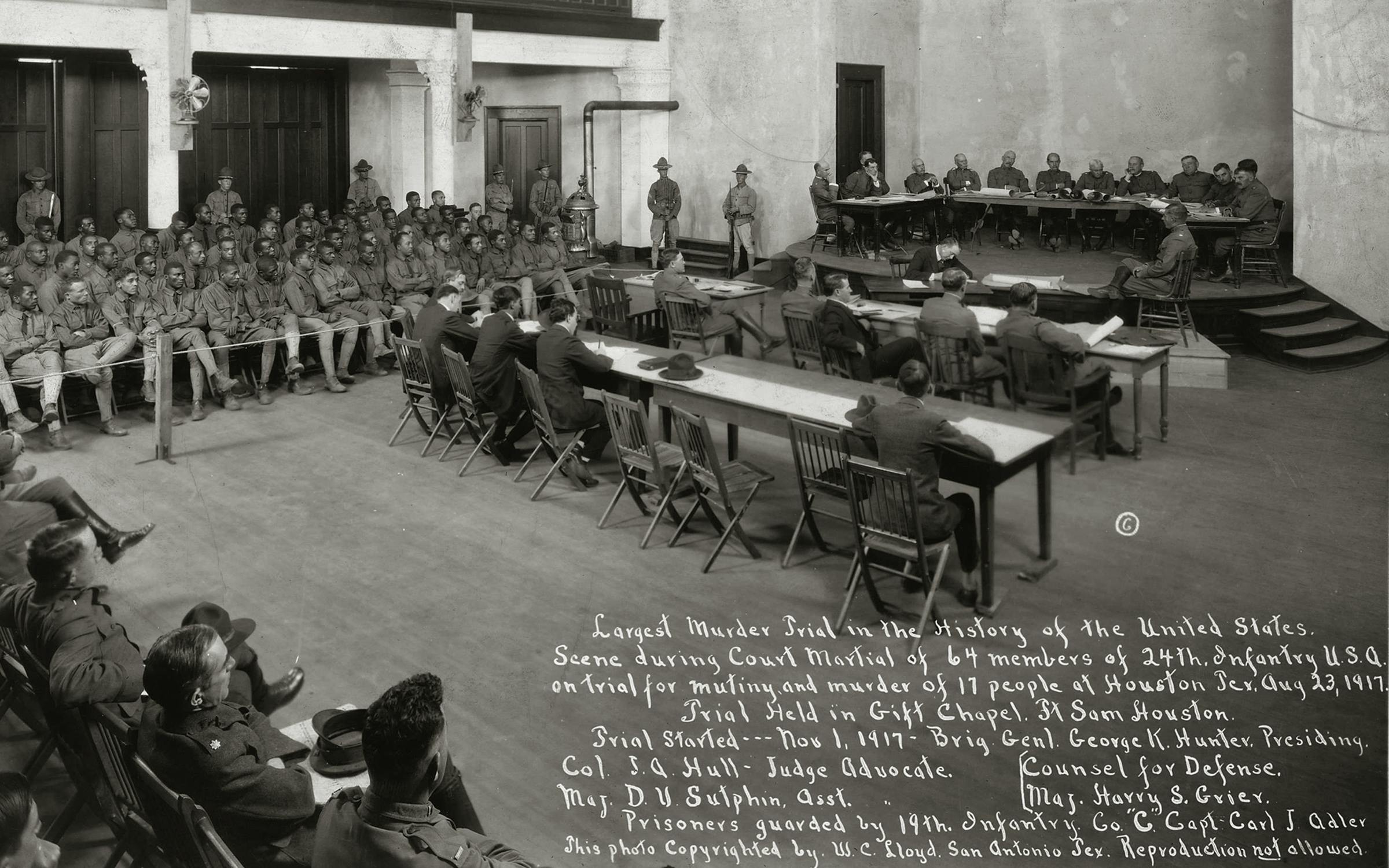

The events dramatized in the film are these: In July 1917, three months after the U.S. entered World War I, the Army sent an all-Black unit from Columbus, New Mexico, to Houston. The members of the 24th Infantry’s third battalion were among more than 350,000 Black soldiers who served in segregated units during the war. The unit’s task was to guard the construction of the new Camp Logan training site (located in what is today Memorial Park). The soldiers endured severe, nonstop racist harassment from civilians, police, and fellow members of the military. After a Black soldier was beaten and arrested for intervening in police mistreatment of a Black woman, tensions boiled over and the soldiers mutinied. The resulting gunfire left sixteen white locals and five Black soldiers dead. In what remains the largest murder trial in U.S. military history, nineteen members of the 24th Infantry were sentenced to death.

Those are the facts. What The 24th powerfully conveys are the emotions. The film begins shortly after the troops’ arrival at Camp Logan, and we watch as the soldiers face abhorrent discrimination and harassment. One soldier is urinated on at the construction site. We feel their shame and their rage as they’re spat on—thick, phlegmy, tobacco-tinted spit. A soldier is brutalized by police for refusing to sit in the back of a streetcar as members of the regiment look on in horror. Soldiers in the unit get held at gunpoint and pistol-whipped by Houston police. Two soldiers are beaten with a sack of grapefruit by Captain Abner Lockhart (Jim Klock). Are they not brothers in arms? Colonel Norton (played by Texas native Thomas Haden Church), the most senior officer at Camp Logan, seems to be the only decent white man in the entire film. Eventually, Norton accepts a promotion and goes off to fight overseas, leaving the soldiers under Lockhart’s command. He is decidedly less kind.

Willmott uses Boston, played by his co-screenwriter Byers, as the film’s protagonist and guiding light. Loosely based on the real-life soldier Charles Baltimore, Boston is an eloquent, Sorbonne-educated man from Atlanta—a model soldier full of patriotism. One scene finds him reading Booker T. Washington’s Up From Slavery in the evening by lantern light. Washington famously argued against desegregation and civil rights activism, for which he has been met with mountains of critique. Instead, he believed Black Americans would eventually achieve equality by improving themselves through respectable work, selflessness, and usefulness to the community. Though viewers see what book Boston is reading only for a split second, Willmott and Byers make it abundantly clear that not only does Boston subscribe to this philosophy—it’s what drives his life.

Boston arrests one of the town’s more virulent racist civilians, Tommy Lee (Tony Demil), for stabbing a Black civilian to death and receives a hero’s welcome at Camp Logan. Norton informs Boston that he’s the first Black man in Houston to arrest a white man for taking a Black person’s life. Lee is eventually released by a judge, with no charges filed. All of Boston’s peers love him, except Private Walker (Mo McRae) and Sergeant Hayes (Mykelti Williamson). Boston’s light skin and his genteel nature lead Walker and Hayes to believe that he thinks he’s better than the rest of his regiment, chiefly concerned with his personal advancement. Eventually, through his actions and telling the true story of his roots—his parents were born into slavery and died in the Atlanta massacre of 1906—he earns their respect. So much so that Boston’s eventual arrest, which leads to a false rumor around camp that he’s dead, is the catalyst for the riots.

Boston returns to camp after rumors of his death, and of a white mob making its way to camp, metastasize. His face has been bloodied by police, and shots can be heard ringing out near the camp. So a handful of Black troops take up arms and storm through Houston, killing white civilians, vigilantes, police officers, and a car full of National Guardsmen whom they mistake for Houston cops. In reality, only one guardsman (Captain Joseph Mattes) was killed by the 24th Infantry Regiment. The fictionalized account makes the events that transpired that fateful night on August 23 seem inevitable (police and soldiers both wore khaki uniforms), with this one grave mistake serving as a bitter climax to their violent promenade. This version of the story feels far too neat and tidy.

In reality, these impassioned men exacted vengeance and reigned chaos. The film gives the impression that only a few dozen soldiers participated in the mutiny, but every historical account claims there were upwards of one hundred. Willmott’s picture does not show a riot on screen, mostly an insurrection, but hundreds of white men looted hardware stores and pawn shops for firearms that night. The police illegally terrorized Black residents and searched their homes for Black soldiers. Roughly a thousand white militiamen found themselves at a police station, with officers handing out firearms to anyone who’d take one. Mattes wasn’t the only casualty of friendly fire; two Black soldiers were killed by stray bullets from their own regiment. To this day, the Houston riot of 1917 remains the only race riot in American history in which more white Americans died than Black Americans. That is, if you don’t include the nineteen soldiers who were sentenced to death by hanging as a result. Sixty-three Black soldiers received life sentences. No white military officers, police officers, or civilians received any jail time.

It’s mind-boggling that this story has stayed largely under the radar for more than a century. What makes this deserving of little to no real estate in your average textbook? What does it say about racial terror in this country that a group of brave men who took an oath to protect Americans instead opened fire on anyone they saw, including teenagers? Could you imagine how furious and hopeless you would have to be to go down that road? How long would you let your humanity be attacked before you combust?

The 24th is a serviceable film. But, unlike Willmott’s excellent collaborations with Spike Lee, The 24th doesn’t do much to elevate itself beyond cinematic paleontology. This is bewildering because none of the principal characters carry the names of the real men involved in the Houston Riot. They’re inspired by them, but ultimately play as tropes and avatars, not real people. Willmott and Byers create Marie Downing as Boston’s romantic interest, but since the woman is given very little agency, the romance seems extraneous. The town racists are borderline cartoon villains. None of the characters feel fully imagined. We don’t know much about them, they aren’t dynamic or interesting beyond what is being done to them or what they do in a compressed time frame. The lack of depth is a missed opportunity. But despite this, the actors give great performances—Mykelti Williamson in particular.

In a documentary about the Houston riot, a descendent of Ira Rainey, one of the white police officers killed that night, asserts that Rainey’s death unleashed trauma and poverty that his family is still dealing with generations later. This is tragic, but if one man’s death can weaken a family for a century, how do we even begin to quantify the generational trauma of slavery, Jim Crow laws, redlining, and police brutality since 1619? That The 24th was released two days before Jacob Blake was shot seven times in the back by a white police officer in Kenosha, Wisconsin, might be seen as prescient. But movies like this always seem prescient. Da 5 Bloods was prescient. BlacKkKlansman was prescient. Crash and The Help (not very good movies) were prescient. A Soldier’s Story was prescient. In the Heat of the Night was prescient. The question is: when will such movies stop being prescient?

- More About:

- Texas History

- Film & TV

- Film