“I salute the Empire of Texas!” President Franklin Roosevelt proclaimed on a June day in 1936 to a crowd gathered at the newly named Cotton Bowl. He proclaimed it to the rest of the country as well, since his remarks were being broadcast nationwide. Texas, for once, was the place to be. The Texas Centennial Exposition, in Dallas—designed and built in a mere ten months to celebrate a hundred years of revolution, nationhood, statehood, secession, and blustery regional identity—was the state’s coming-of-age gift to the world and, more crucially, to itself. The frontier past was over, and all the marvels of the twentieth century were on spectacular display.

Among the proposed goals of the Centennial was to “Texanize Texans” and to create an extravaganza “bold enough to please the still hearts of Austin, Travis, and Houston, and big enough to mirror the accomplishments of Texas to all the sons and daughters of earth.” The Exposition’s art deco–inspired architectural style was labeled “Texanic.” The Big Show, a B movie starring Gene Autry, was filmed mostly on location at the Exposition, and if you watch it today you can get a sense of the scale and the self-conscious spirit of the event: rows of marching Texas Rangers; the grand esplanade flanked by colossal buildings with stately symbolic statues; and the vast stage of the Exposition’s biggest attraction, the Cavalcade of Texas, a pageant in which the state’s history was depicted in a flurry of galloping horses, ever-changing sets, and pioneers driving their wagons across the lonesome prairie. Elsewhere on the grounds were a replica of the Globe Theatre, full-size robotic dinosaurs, and attractions such as the Streets of All Nations, which provided visitors with an anthropological excuse to watch a nude woman dive into a flaming pool of water. At the center of it all was the State of Texas Building, a somber palace consecrated to the noble idea of Texas. Former governor Pat Neff declared the building to be the “Westminster Abbey of the Western world.”

Has there ever been a state that tried so poignantly hard, that wanted so desperately to believe in itself and to ensure that that belief was passed on to subsequent generations? We’re a long way from 1936 and its high-water mark of Texas exceptionalism, but that please-notice-us legacy still endures. I’ve never been immune to it, and I don’t think I’ve ever been exactly opposed to it, but because I came of age in a very different time—the counter-triumphalist sixties and seventies—I’ve always been squeamish and suspicious about the notion that Texas is, or at least has to be regarded as, the promised land.

It’s an attitude that probably seeped into my identity as a father. I wasn’t one of those proselytizing Texas dads to my three daughters, forever schooling them in the glories of their native state. I was too conflicted to play that role. But at the same time, there was something I didn’t want them to miss, the sense that they didn’t simply happen to live in Texas but were from here. There was just enough family history to justify some kind of aura of destiny. Though I was born in Oklahoma, somebody on my father’s side of the family was said to have fought at, or been at, or been in the vicinity of, the Battle of Sabine Pass during the Civil War. Through my wife’s family, the girls could trace their lineage back to a Georgia doctor named William McMath, who joined up, in 1842, with the ill-advised Mier Expedition, an attempt by an army of piratical Texans to seize parts of northern Mexico. Some of the men were later captured, and every tenth one was ordered to be executed, their fate determined by whether they drew a white or a black bean. I remember telling my children that they would not exist if some homesick, blindfolded guy rotting away in a Mexican prison in 1843 had not had the good fortune to pluck a white bean out of a jar, but they just gave me that please-do-we-have-to-stop-at-another-historical-marker look.

They were, I suppose, understandably wary. If I put myself in their place, I would have to understand that “Huh” was the only reasonable answer to a question like “Do you girls realize you’re looking at possibly the last remaining Spanish mission aqueduct?” Or that when they innocently asked, “What do you want for Father’s Day?” they did not mean they were ready for a two-hundred-mile round-trip to inspect the original site of Washington-on-the-Brazos.

As they grew older, though, pride of place inevitably took hold. The younger girls, Dorothy and Charlotte, went to college in New York and then worked in the city at purportedly glamorous jobs for a few years before coming home. It was the old story: they moved to New York for the excitement and opportunity, they moved back to Texas for the queso. Among the other things they badly missed, they told me recently, were giant-sized iced teas in Styrofoam cups; swimming holes; long, empty roads where the drivers in their pickups would give you a hi sign as they passed; and not having to explain to people what happened at the Alamo.

But you can’t step into the same Texas twice. In the few years they had been gone, the state had become a subtly different place: more and more strip malls and chain restaurants had continued to fill in the open highway stretches between cities; favorite hangouts and hideaways had either closed or exploded into unbearable hipster meccas; rent was up and jobs were scarce, though not as scarce as they were in the rest of the country during those recession years.

While they had been away, there had been a quiet, momentous shift in demographic history: the growing minority populations had finally overtopped the white, non-Hispanic majority, which had been calling the shots in Texas since 1836. This fact was in vibrant evidence a few months ago when I went to my niece’s law school graduation at the University of Houston. There was her name—Margaret Sharp—in the program, along with a hundred or so other Anglo-sounding names, but there were enough graduates with names like Aamir Shahnawaz Abdullah, Obiajulu Nnebuogo Enaohwo, Janie Ann Kunnathusseril, and Innocent Ifechukwu Obeta to make you wonder whether a singular Texas identity had long ago become a remnant notion, dissolved into a globalized future.

But it would be a mistake to think that the Texanizing of Texans is entirely a thing of the past. A few weeks after my niece’s graduation, I was standing in the middle of the Odd Fellows Cemetery in San Antonio for a memorial service for my historian friend Kevin Young, who had died unexpectedly at the age of 55. Kevin had been living in Illinois, but because he had lived so long in Texas and much of his work had been centered on the Texas revolutionary period, it was important for his friends to see him off someplace closer to home. They chose the cemetery where the ashes of some of the cremated Alamo defenders were said to have been buried.

We stood in the sun as two guys in cowboy hats strummed their guitars and performed “The Ballad of the Alamo” and “The Green Leaves of Summer.” After the eulogies, a group of reenactors in 1830’s clothing marched forward and delivered a 21-gun black powder salute. As they reloaded, I noticed a teenage girl who was standing in front of me. She was wearing a tank top, and tattooed on the back of her shoulder were the closing words of William Barret Travis’s famous letter of defiance from the Alamo. The rendering of his handwriting was exact. “Victory or Death,” the tattoo read. “William Barret Travis, Lt. Col. Comdt.”

I remembered standing in front of a framed copy of that letter with my oldest daughter, Marjorie, when she was about the age of that girl in the cemetery. I had dragged the kids to the Alamo yet again, one of those dad-trips that they had learned to endure with sarcastic forbearance. But this time was different. Marjorie read the handwritten letter slowly, carefully—“Our flag still waves proudly from the walls—I shall never surrender or retreat”—and fifteen years later she named her second-born son Travis.

It wasn’t just because of the letter. She and her husband, Rodney, had always liked the name Travis, she told me, just as they had liked the Texas-sounding name Mason for their older son. The sounds of those names, their accidental or on-purpose historical resonance, reinforced the idea that your destiny has something to do with where you’re from and with the past that made that place what it is. The stories gathered in the pages of this special issue speak to that idea, to the sense that there is still something eternal about Texas, still something that people want to hold in common and preserve, though their own experiences growing up in the state, or adapting to it after arriving here from elsewhere, can be as different as Gene Autry’s from Obiajulu Nnebuogo Enaohwo’s.

This summer, I took my two grandchildren on a field trip to the site of the Centennial Exposition, which had taken place 76 years earlier and was as far distant in the Texas past for them as the Comanche wars had been for me when I was their age. Fair Park, which encompasses the buildings of the Exposition, including the Cotton Bowl, is still a periodically thriving place, home to football games, the State Fair, the Children’s Aquarium, and the Museum of Nature and Science. But in the middle of an uneventful June day, there was no one around as we walked up the stairs of the Exposition’s long-ago centerpiece, the State of Texas Building—now known by a more imposing name, the Hall of State.

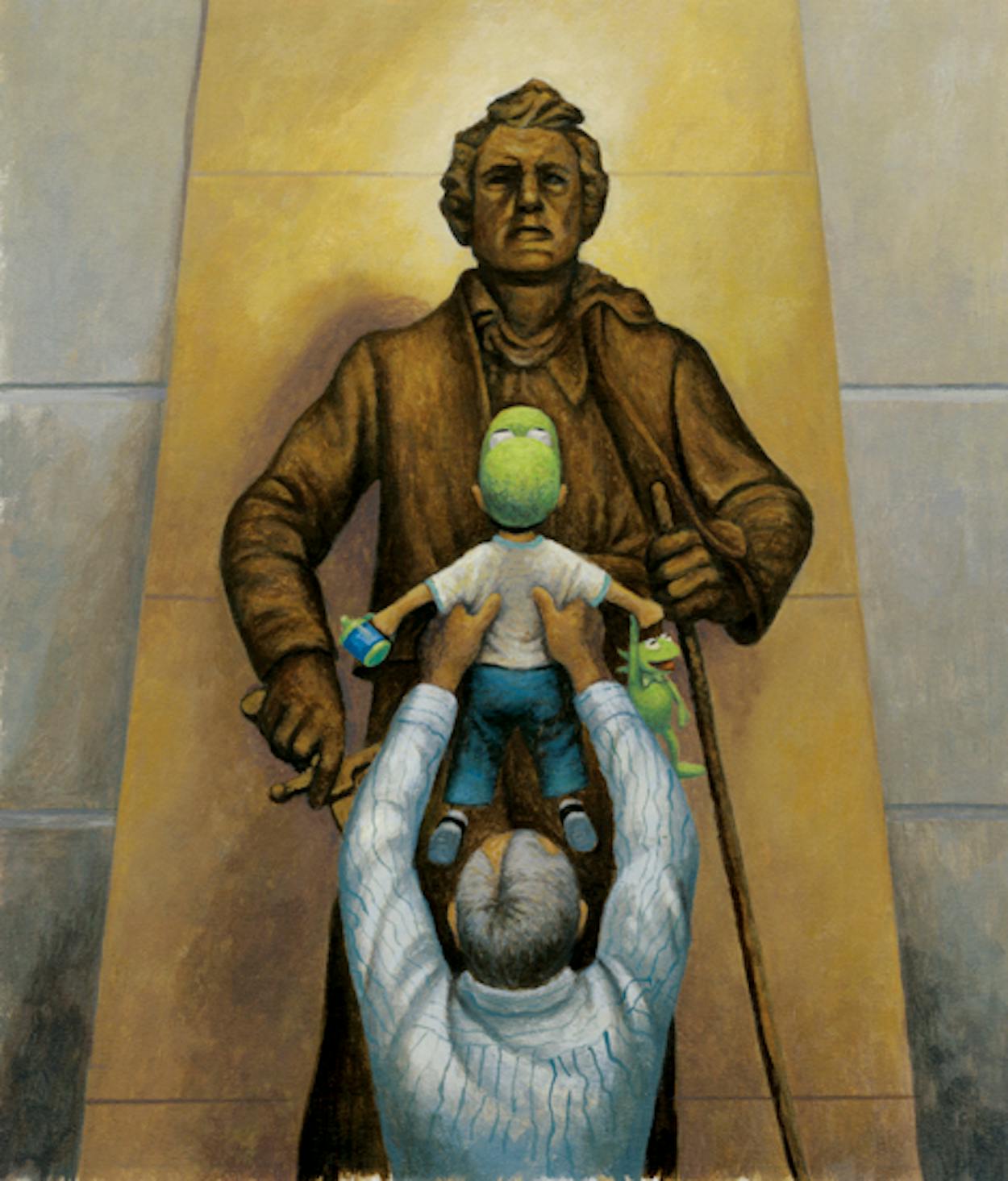

We stared at the massive bronze doors, and above them, Tejas Warrior, a gilded statue of an Indian drawing a bow, and above that, the soaring limestone pillars forming a semicircular portico. Four-year-old Mason was wearing a Handy Manny Halloween costume whose icky polyester fabric should have been unbearable on a blazing summer day, but his attachment to it was profound and unyielding. Travis, who was two, never went anywhere without his lime-green Kermit the Frog cap.

The two of them were an incongruous sight at this earnest shrine to Texas ideals past, but the truth is that anybody at all from our own time would have seemed incongruous at the Exposition grounds that day. They were so empty—and so, well, Texanic—that they looked like the ruins of a vanished civilization. In front of the Hall of State was the esplanade of the fair, featuring a reflecting pool whose fountains were programmed to dance in rhythm to “The Yellow Rose of Texas” and huge exhibition halls, which had once demonstrated the coming marvels of electrical and automotive technology. The main buildings had all been restored, their heroic murals—depicting thirties visions of space flight and medicine and farm productivity—uncovered and repainted, their rather hideous but also rather wonderful symbolic statues patched up or even recast.

We took all this in from our vantage point outside the Hall of State and then walked through the bronze doors to the hushed gallery known as the Hall of Heroes, where I lifted Travis up to gaze indifferently at Pompeo Coppini’s statue of his sort-of namesake, William Barret Travis, his sword unsheathed to draw that legendary line in the sand.

The Hall of State’s purpose is rather obscure. It is short on actual exhibits, though there is a small museum in one of its wood-paneled side rooms, and there are display cases in the Hall of Heroes, one of which—nestled between the statues of Mirabeau B. Lamar and Stephen F. Austin—pays homage to Mariano Martinez, the Dallas inventor of the frozen margarita machine. Otherwise the building seems to be all about brute inspiration. When Mason and Travis entered the Great Hall, a four-story-high empty room adorned with massive murals featuring sinewy, stricken-looking Texas heroes, they stared in awe at a gold medallion as big as the sun on the far wall.

“What are those guys holding?” Mason asked me when he finally turned his attention to the murals.

“Guns.”

“Why do they need those?”

Long story. How was I supposed to explain the Goliad Massacre to a four-year-old in a Handy Manny costume? He and Travis, two tiny little figures in this vast, echoing chamber, were clearly working to take it all in, and I had the feeling they would be a long time sorting it out. This 1936 vision of Texas—with its tonsured Franciscan friars, sinister conquistadores, muscle-bound Indians, gushing oil wells, and be-gowned women holding aloft torches—seemed overwrought and otherworldly even to me, less like a history lesson than like some kind of collective anxiety dream.

After we left the Hall of State and Fair Park, I decided—in case my grandchildren had not been imprinted with enough Texas lore—to swing by Pioneer Plaza, in downtown Dallas. This is the site of not just the city’s oldest cemetery but also a shock-and-awe art installation: a larger-than-life-size sculpture depicting a group of wranglers driving a herd of seventy Longhorns across a man-made stream. We approached the sculpture through the old cemetery, which was full of broken granite slabs inscribed with the weathered names of the pioneer grandees of Dallas and, often, their infant children. This prompted a battery of questions from Mason about death and burial that was interrupted when the boys discovered the bronze cattle herd making its sinuous way down a steep slope and across the water. Travis, gazing up at the statue of the trail boss, offered something appropriate from his vocabulary: “Yeehaw!” Other than that, the boys did not seem to be particularly stirred. They were growing up with Handy Manny and Yo Gabba Gabba!, not, as I had, with Hopalong Cassidy and Davy Crockett.

“Why is he riding a horse?” Mason sincerely wanted to know. His idea of a solitary range rider did not reach farther back than Lightning McQueen. I filled him in as best I could on the Industrial Revolution and then asked him why he thought all those cattle were crossing the river.

“Don’t ask me! How would I know?”

We left it at that—no need to launch into a history of the Kansas railheads or, for that matter, the slaughter of animals for food—and got back in the car, driving north on Griffin Street. We turned left on Elm and were heading toward Stemmons Freeway when I saw the white X in the middle of the street and realized I was driving them past the old Texas School Book Depository and through the dark shadow of history.

I kept driving without saying anything to the grandkids, but the next day I went back by myself. It had been years since I had been to the Sixth Floor Museum or stood in Dealey Plaza, looking at the assassination site. It was more of a touristy hub than I remembered, with self-appointed guides aggressively trolling for clients on the sidewalks and assassination theorists holding forth in front of tables laden with conspiracy books and DVDs and gruesome illustrations of the fatal head wound. A sign near the museum entrance read “Come Enjoy a White Chocolate Cherry Iced Mocha.”

A tasteless yellow banner planted in the grass read “Grassy Knoll.” I was standing in the pergola at the summit of this infamous slope when I noticed a white horse-drawn carriage clomping up beside the front door of the building that had once been the School Book Depository. Riding in this fairy-tale conveyance was a Muslim family, the father stretched out, half reclining on one of the bench seats, his wife and an older woman sitting on the other, along with a girl who looked about ten. Both of the women wore hijabs, but the girl was bareheaded, her hair cut into a fashionable bob. I couldn’t hear what the driver was telling them about the history of the assassination but saw that she was gesturing toward the middle of the street below.

Along with the family in the carriage, I followed her pointing finger and saw again the white X that marked the place where Kennedy had been struck in the head by the bullet from Lee Harvey Oswald’s mail-order rifle. It occurred to me that the X stood for something else as well: the moment when that old idea of Texas—the unquestioned pride behind the Centennial Exposition—gave way to something murkier and less certain, a Texas that could not be so easily celebrated and passed down from parent to child without a haunted note of ambivalence.

If that X seemed to mark the birth of modern Texas, I had to remember it was modern only to someone my age, for whom the events of Dealey Plaza were still magically raw. Someday I would tell Mason and Travis what it felt like to hear my high school principal’s voice come over the intercom and announce that the president was dead. I doubted, though, that I could really convey that sense of horrible amazement, the feeling that a trapdoor had just opened, and I was no longer in my algebra class but alone and lost on some new plane of reality.

For my grandchildren, for that little girl in the Cinderella carriage, for the young couples who were born after 1963 and were now drinking white chocolate cherry iced mochas in front of the School Book Depository, that long-ago moment could only be the historical past, a trauma from a distant time heard about, read about, in the undying present. The cavalcade of Texas keeps moving on, a Centennial here, an assassination there. We may like to think that through it all there is something indefinably, steadily the same, something to hold on to. But that determination belongs to history, not to us. That is the way it has to be, the way it should be, and the way it shall be unto the Texas generations.