I t was only a couple of weeks after my father left that my mother made it clear: I was now the man of the family. I spent a long time looking at myself in the mirror that night, like a third stringer psyching himself up after finding out that he’s starting the second half of the big game. It was 1980, and I was fourteen. My parents had split after two years of agonizing indecision, intense anger, and madness as unrelenting as the San Antonio summer. My father had gone over to the other side, joining what my grandmother called el mundo. He wasn’t saved anymore. A talented guitarist, he’d always played for God, performing on the Spanish church tour with its puny adulation and chump-change offering plates. Now he’d taken off with a buddy’s band to play the devil’s music, conjunto, in far-flung and exciting places like Chicago and Los Angeles.

Meanwhile, we had become poor overnight—government-cheese poor. The people at church looked at us with pity, whispered about los pobres. Abandoned by my father but not by God, we soldiered on, my mom and five kids all sleeping in one bedroom, huddled together, needing to hear one another’s voices.

But self-pity was weak, and my mom wasn’t about to allow her eldest son to give in. “You have to get a job,” she told me at the end of the man-of-the-house speech. She knew a woman who ran a molino and was willing to take me on for weekend work. The barbacoa restaurant needed another cleaner and counter jockey. Straight-up sweat work, but it paid two bucks an hour, twelve hours a day, cash money.

From then on, each Saturday and Sunday, I’d get up in the still-dark morning to ride my bike to work. The route took me past the San Fernando Cemetery—huge, the size of a dozen football fields—and El Rapto, the evangelical church we attended, where my uncle delivered terrifying weekly sermons featuring the apocalypse and the alarming possibility that God’s favor was determined by a cosmic game of dice. Finally, after narrowly escaping the packs of wild dogs and angry roosters that roamed the winding, pothole-filled streets of the West Side, I’d pull up in front of an ugly beige building with a beat-up sign that read “Tamales Tortillas y Menudo.”

The doors opened at 6 a.m., and customers came nonstop. Twelve hours straight of people ordering in supersonic Spanish, handing you a mash of sweaty ones and fives while you scooped up servings of gray sesos and slithery lenguas that resembled stiff, skinned eels. Back in the kitchen, the cooks worked even harder. They started their day at 3 in the morning, stacking cow heads in an enormous pressure cooker that radiated furious heat and looked big enough to power a locomotive. After the heads were cooked, the guys lined them up and scraped off everything that was remotely edible: brains, eyes, tongue, and every bit of meat, each separated into its own aluminum bin. It was like Dante’s ninth circle of bovine hell. The cooks were constantly daring one another to swallow the most vile scraps of flesh and once living tissue imaginable, always with the question, “Are you a man?”

The cooks were all from Mexico, short dudes, most of whom didn’t speak English. They were a fraternity of paisanos who knew the rules of living in the shadows. They wore sweat-stained baseball caps and cowboy boots and sported mustaches, and all of them were indisputably, incontrovertibly men, the way I wanted to be a man, strong and assured, with easy laughs and good stories. They didn’t pay attention to me, a scrawny pocho, but I studied them carefully. There was Juan, who wore a prosthetic nose because he’d blown off the original while cleaning a shotgun. Ivan, who was the oldest and much respected for his barbacoa know-how. And Ernesto, whose job was popping the eyeballs loose and cutting the membranes away to get at the mushroomy meat with a dirty fork. Then plop, plop, plop into the bin.

Ernesto eventually became my pal. He was only a couple of years older than me and lived in Alazan-Apache Courts, one of the most violent places in San Antonio. That part of the West Side was overrun with railroad tracks and drainage canals that tried to keep the arroyos in check. There was a matadero that smelled so bad you had to roll up the car windows to keep out the sickly slaughterhouse stench. He was all about barrio rules, always ready to throw hands, and claimed to have had carnal relations with many a beautiful ruca. Best of all, he was unafraid.

When I could make an excuse about working late, Ernesto and I would cruise our bikes over to his father’s bar. It was an old-school cantina on Castroville, and he didn’t mind serving minors so long as they were his son’s friends. There was a free pool table, a jukebox with tons of conjunto, and an assortment of barflies and burnouts, a posse of failed fathers and ex-husbands. But at least Ernesto’s father was around. He made a fuss over us, bragged about his son to the other men. He owned a sweet ’75 Monte Carlo that he’d spray-painted matte black, with a big-block V-8 and a Mexican flag attached to the antenna. It was the Mexican Batmobile. He’d send us out in it when he needed an errand run. We always took our time, cruising Zarzamora, Bandera, Culebra, Rosedale Park. All the places my mother warned me about and which now composed the backdrop of my new reality. Late Saturday night, Ernesto and I would drink beer at Woodlawn Lake, sitting on a park bench and talking about the customers, girls, whatever, all the while daring anyone to mess with us as we speared empties into the water. If this wasn’t manhood, it was as good an approximation as I could imagine.

One Sunday, in the middle of smearing congealed grease around on the yellowed Formica countertop, I looked up to see my father walk in. He lined up like a regular customer, waiting his turn. He had someone with him, a woman I’d never met. It’d been months since I’d seen him. Two of my siblings’ birthdays had passed since he’d last called. It occurred to me that maybe he was trying to show support by being there, an awkward attempt at reconnecting. But I wasn’t even sure if he knew I worked there. I went to the back. I didn’t have anything to say to him.

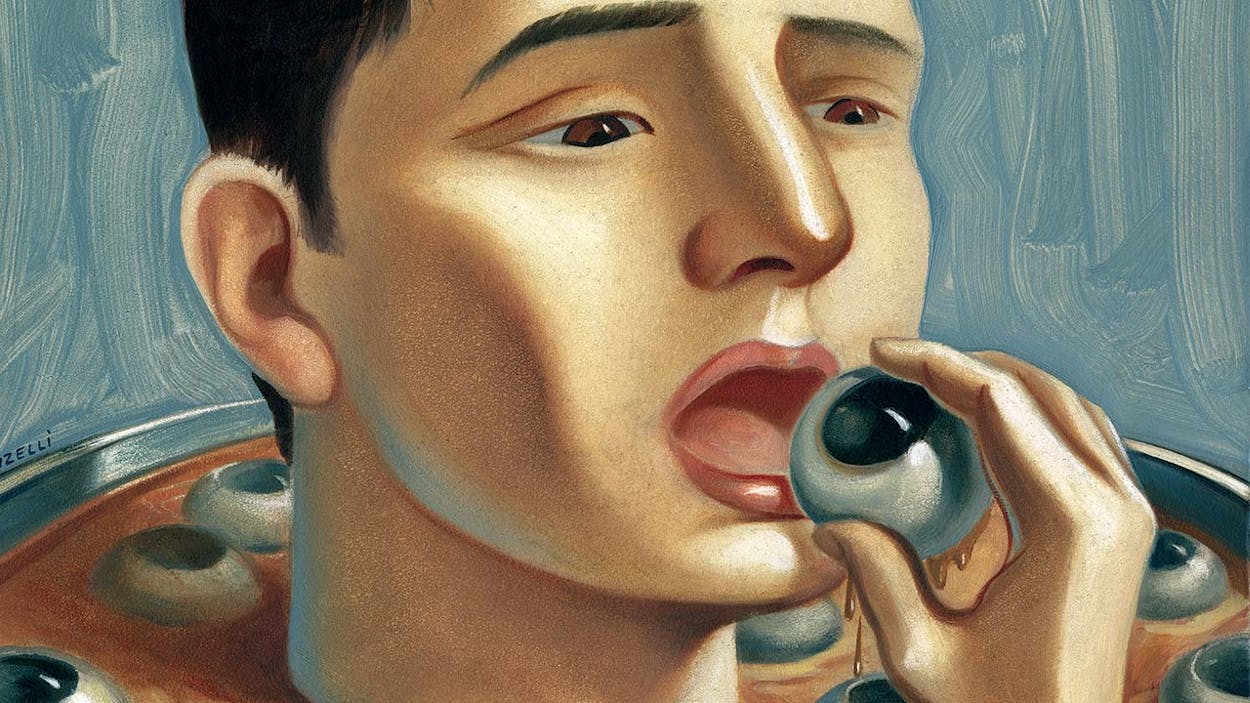

Ernesto was bent over a bin of five dozen eyeballs bobbing in murky water. “Give me one of those,” I said. He smiled widely and scooped his palm into the tub. “What you want an ojo for?” “I just need it,” I said. Ernesto opened his hand and held out a pair of wrinkled, lidless eyes. “You hungry, then?” he said. The other cooks stopped scraping and clanging and elbowed one another. “You got huevos or huevitos?” he asked, cradling the slimy pair, about the size and consistency of peeled hard-boiled eggs, at his crotch.

Through the serving hatch I saw my father nearing the front of the line. Without thinking, I grabbed the eyeballs and in one smooth motion sank my teeth into the optic nerve of one, spit it back into Ernesto’s bin, and popped the eyeball into my mouth. A wave of nausea hit me as I rolled the giant, chewy slug across my tongue. I chewed once or twice, then swallowed the whole thing. A roar of raucous approval went up from the cooks. “That was good, mano!” Ivan said, thumping my back. “You’ll see better now.”

I walked back up front and intercepted my father’s bag before he paid. All he’d ordered was a dozen tortillas de maiz. I slipped the other ojo into his bag without his noticing. Then I stepped in front of him and handed over the bag. As he reached out with a handful of crumpled ones, he glanced at me, then did a double-take. He grabbed the woman’s hand and turned away, not bothering with the change. He didn’t speak a word.

When I got off work a few hours later, my mom was waiting out in the dusk in our beat-up Dodge, my brothers and sisters along for the ride. I put my bike in the trunk and got into the front seat. I didn’t say anything about my dad coming in. I just fanned out the weekend’s $48, handing it over. “Look, I brought us something to eat.” I held out a brown paper bag, shiny with grease. “Two pounds of all-meat.” The kids were elated, jumping on the seats, and even my mom looked happy for the first time in a while. I leaned back and closed my eyes, tired and sweaty. It was just us and it was okay. And damned if I wasn’t a man.