Terry Daniels welcomes me to his home with a firm handshake, a startling reminder that once, long ago, his right jab was a fearsome entity. His voice, though, is faint. His 68-year-old body shakes like that of an older man. His close-cropped hair is snow-white.

Daniels’s brother Jeff, who has brought me to this one-bedroom apartment in an assisted-living center in their hometown of Willoughby, Ohio, had warned me that Terry’s memory doesn’t always “rewind” adequately. But when I ask Terry about the unlikely events that led him to fight Joe Frazier for the heavyweight championship of the world, in January 1972, his memory kicks in immediately.

“The promoter called and said, ‘Terry, are you sittin’ down?’ ” he says, his dark eyes brightening. “ ‘Well, you’re going to fight Joe Frazier.’ ”

“You mean an exhibition fight? All right! That’s great!” Terry had replied. He was 25 years old then, an Ohio transplant to Texas who was only a few credit hours short of graduating from Southern Methodist University.

“No, you’re fighting for the title,” the promoter told him.

“Are you kiddin’ me?” Terry said. “I’m not even ranked in the top ten!”

“Yes, you are. You’re number nine right now.”

“Then I sat down,” Terry recalls.

“You had to have been on cloud nine,” says Jeff, a semi-retired investment broker.

“I was,” Terry quickly replies.

Nothing in the decor of this apartment suggests that its occupant briefly shared the spotlight of American sports 43 years ago. No promotional posters. No framed photos. There are only three keepsakes of any kind adorning the living room walls—a plaque marking Terry’s induction into South High School’s sports hall of fame; another plaque presented by the Grand Prairie Jaycees in appreciation for his participation in their January 1973 boxing tournament; and his framed SMU diploma, dated December 22, 1972.

Daniels today weighs only slightly more than his fighting weight of 190 pounds, but so much else has changed. In the early nineties, he was diagnosed with a form of Parkinson’s disease that had likely been exacerbated by countless blows to the head. A decade later, a doctor told him that he had only a few more years to live. He outlasted that diagnosis, but his decline has been severe. In 2004 Jeff moved Terry back from Texas to their native Ohio. Two years ago, Terry settled into Breckenridge Village, which is located right next door to South High, where he was a three-sport star half a century ago.

During our visit, Jeff often helps his brother walk, gently placing a hand on his arm. Terry says he uses a walker when he’s alone in the apartment. “I stumble from one chair to the next,” he says with a sheepish grin.

It’s a long fall from cloud nine to a ground-floor unit in Breckenridge Village. But the night when Daniels faced the world’s heavyweight champion in New Orleans is intimately connected to his present circumstance. Before that night, Daniels was a talented young boxer who had put college on hold, but he was hardly a major contender. The predictable path for someone of his background and education would have been to fight for a few more years at most and then settle into a conventional career. But the greatest night of Terry Daniels’s life pushed him in another direction—six more years of full-time boxing, with few victories to show for the brutal pounding taken by his head.

As a young man, Daniels was an unlikely candidate for a life in the ring. The five Daniels children, of whom Terry is the oldest, were often asked by friends if they had any connection to the green Daniels Fuel trucks that drove through town. They did; the family owned a number of local businesses that were started by their grandfather, and Terry could have eventually assumed a managerial position in one of them. But he was always eager to set out on his own. His decision to attend college more than a thousand miles from home was just the first of his small rebellions.

When Daniels tried out for SMU’s football team as a freshman in the autumn of 1964, he aggravated a serious knee injury that he had suffered during a high school game. A return to the gridiron, he was told, just wasn’t possible. The injury wasn’t debilitating, though; he pitched for the Mustangs baseball team and took up boxing to stay in shape. Eventually he became a regular at Dallas’s Pike Park gym and entered the city’s Golden Gloves tournament. His father wasn’t happy about it. “I didn’t send you down there for that” is how Jeff recalls Bill Daniels’s reaction. But Terry’s amateur success over four years—three city championships and one state heavyweight title—prompted him to turn pro in 1969 and delay completion of a degree in political science.

Daniels’s fledgling fighting career was nurtured under the guidance of trainer Ronnie Wright and manager Doug Lord, a Dallas insurance executive by day whose stable of area boxers included world welterweight champion Curtis Cokes. Compiling a record of 23 wins, 1 loss, and 1 draw against modest competition during his first two pro years, Daniels was a relentless puncher who could absorb extensive punishment. As he moved on to more-challenging opponents, the victories grew harder to come by, though that didn’t always discourage him. He lost a unanimous decision to nationally ranked Tony Doyle in February 1971 but was glad to last all ten rounds. Another defeat three months later—a ten-round decision to former world champion Floyd Patterson before a roaring hometown crowd in Cleveland—actually bolstered his reputation.

Then came the stunning upset that October of heralded Ted Gullick, who entered the ring with fourteen knockouts in eighteen outings. Gullick left the ring early in the third round, floored by Daniels’s vicious right. Promoter Don Elbaum—the tireless barker who brought Don King into the sport—began piecing together the possibility of pitting Daniels against Frazier in New Orleans the night before Super Bowl VI, which was to be held in the Crescent City. Daniels’s manager, Lord, saw a possible marketing synergy. Earlier that year, the Dallas Cowboys had lost their first Super Bowl game on a last-second field goal. By late November, they were once again leading the NFC East. If the Cowboys made it to Super Sunday once again, Daniels could share in the hype devoted to his adopted hometown’s team.

Boxing pundits rated Daniels as the biggest underdog in a heavyweight title fight since the mid-fifties. Not that a serious challenger was really desired. Frazier’s first appearance since “The Fight of the Century” against Muhammad Ali ten months earlier was intended to whet the public’s appetite for a more alluring matchup in the future, possibly with 1968 Olympic gold medalist George Foreman, of Houston. Daniels understood his role. “They wanted an easy test,” he told the Dallas Times Herald.

As sacrificial lambs go, Daniels had a lot working in his favor, especially the fact that he was Frazier’s polar opposite. Frazier was the rural son of South Carolina sharecroppers; a New Orleans Times-Picayune sports columnist called Daniels the “son of a millionaire.” That probably wasn’t accurate, but Lord didn’t discourage any embellishments. Daniels, one in the long line of “Great White Hopes” who have existed since black fighters began to dominate the sport midway through the twentieth century, sang in the high school choir, was treasurer of his junior class, and began his SMU days studying engineering. He delighted the national press with his choice of reading (a book on psycho-cybernetics) and hobbies (crocheting, to keep his hands occupied). Sports Illustrated observed that Daniels “may be the most articulate pug since Gene Tunney.” Ali said, “Outside of me, he’s the prettiest boxer around.”

And so on Saturday night, January 15, 1972, Daniels entered the ring at Rivergate Auditorium wearing pink trunks with “Terry” sewn down the right side and blew kisses to the crowd. Frazier, three years older and almost 24 pounds heavier, wore trunks and a robe of kingly purple and hopped about as if already facing an unseen opponent. The fighters were both about six feet tall, which worked in Daniels’s favor; the champ was more comfortable fighting taller opponents.

“I wasn’t scared,” Terry says. “I was ready to go. I expected him to chase me down and beat me to a pulp if he could.”

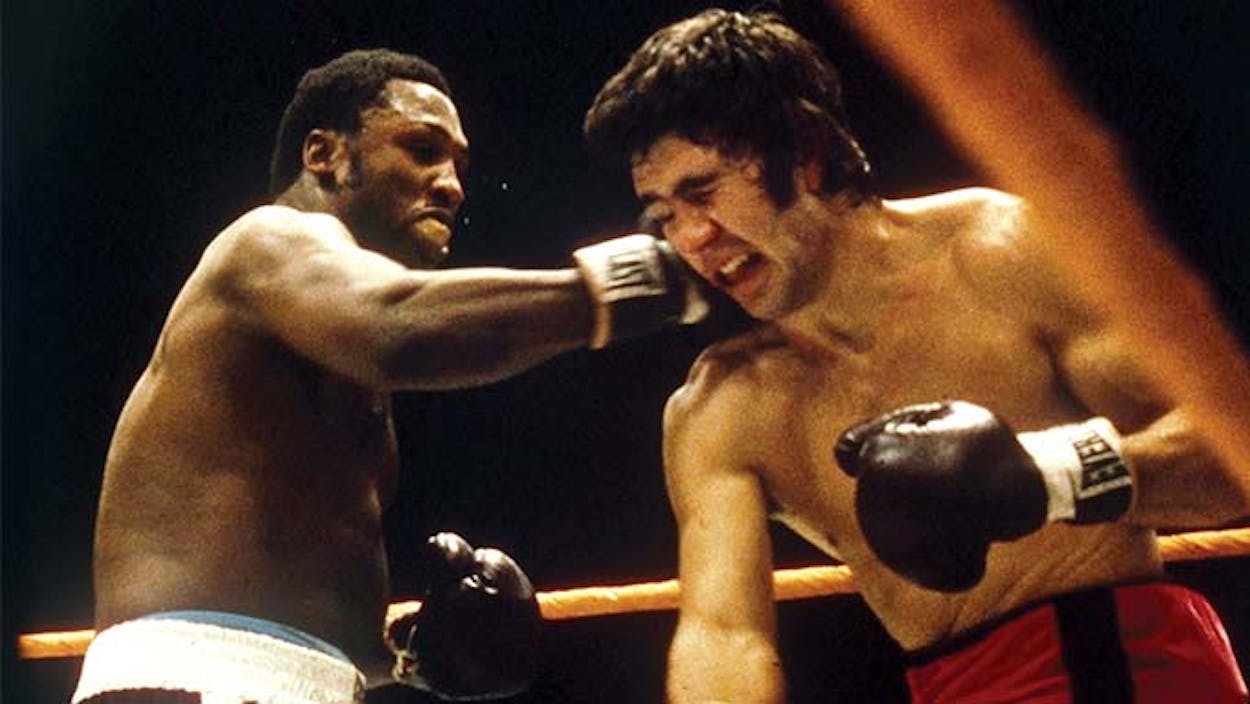

The black and white footage of the fight, available via YouTube, demonstrates that Frazier wanted to do precisely that. After the opening bell, he charged from his corner and worked the head more often than usual. Daniels was first knocked down by Frazier’s left hook in the closing seconds of the opening round, falling forward to the canvas and rising just in time to avoid being counted out. In the second round, Daniels gamely continued his own attack, which appeared to have no effect on Frazier. The challenger flailed and danced and ducked and even lost his mouthpiece.

“I’m sure Terry had Frazier confused or concerned,” Jeff says, “because, by that third round, he came after Terry like a freight train.” In the third, Daniels was knocked down twice by left hooks, compelling some fans to yell for him to stay down. In the fourth, Frazier sent Daniels halfway through the ropes before he sank to one knee on the canvas, and the referee stopped the bout.

In his corner, an exhausted Daniels leaned on the top rope, his head resting on folded arms, crestfallen that his opportunity had come and gone so quickly. But during the post-fight interview session, he breezily joked about how often he’d been sent to the canvas: “They must have needed a math major to count so much.”

The next day, Daniels sat on the 50-yard line at Tulane Stadium and watched his beloved Cowboys beat the Miami Dolphins to win their first Super Bowl. “Next Year’s Champions” were on their way to becoming “America’s Team.” It was a good weekend.

After Daniels’s decisive loss to Frazier, Lord urged him to quit boxing. He knew that Daniels’s career had peaked, and unlike so many boxers, Daniels had options outside the ring. But Daniels wasn’t ready to give up. The $35,000 purse for the Frazier fight (the champ was guaranteed $250,000) was more than the average pro football player made in a year back then. He’d had a taste of the limelight, and he liked it. “Terry told me, ‘No, I want to fight again,’ ” Lord recalls.

Lord, it turned out, was right. Before the Frazier bout, Daniels was 28-4-1. Over the course of the nine years that followed, he went 7-25, beginning with 5 consecutive defeats that ended any chance of being highly ranked again. His lone return to prominence came in October 1972, when he was among a passel of pugilists who faced Ali in an exhibition staged in San Antonio. He re-enrolled at SMU that same year and got in his remaining hours, taking Twentieth-Century Political Thought, History of Christianity II, and Sociology of Law. He retired from boxing in 1978 after a tough defeat in Chicago, came out of retirement in 1981 for a bout that he lost in a second-round KO, and then hung up his gloves for good.

A few months later, he relocated from the Dallas area to Houston, where he operated a court-reporting business that was owned by his former trainer, Ronnie Wright. The first signs that something was wrong came soon after, when he started noticing tremors in his left hand. Then things got worse. One day at Dallas–Fort Worth International Airport in the late eighties, Wright recalls, a flight agent mistook Daniels’s struggle to maintain his balance as inebriation and was reluctant to let him board his plane.

When he was finally diagnosed, it wasn’t much of a surprise; by then Ali too had been diagnosed with Parkinson’s, yet another link between the two “prettiest boxers.”

Sitting in his apartment, Daniels seems uninterested in self-pity. “I accepted it,” he says of his condition.

“He just ignores it,” Jeff says. “He ignores the pain.”

Jeff, who was himself an amateur fighter, explains his brother’s reluctance to leave the sport by referencing other fighters. “Even Frazier hung in longer than he should have,” he says. “They all did. Ali.” And, to be fair, the harm caused by so many concussive blows to the head wasn’t understood decades ago.

One reason Jeff thinks about this so much is that he’s writing a book about Terry. My Brother the Boxer, which doesn’t have a publisher yet, will end with the title fight, though an epilogue will note Terry’s current disability. Jeff’s proposed cover photo is a promotional pose from the Frazier bout, of Terry smiling at the camera while leaning over the ropes. “I wanted people to remember him exactly that way, at the peak,” he says.

But talking to Terry today, as he quietly follows the flow of a conversation and only occasionally chimes in, it’s impossible to forget that he chose not to let that peak be his only legacy. The professional decline that followed, and the physical and mental decline that followed that, turned his story into a cautionary tale.

I ask him if he seriously considered quitting boxing after his title shot.

“Yeah,” he says. “But not too seriously.”

Was fighting Frazier worth it?

“Worth it? Yeah. Sure,” he says. “It gave me a little more money. I lived like a rock star for about six months.”

- More About:

- Sports