Near the end of his extraordinary new book, Run, Brother, Run: A Memoir of a Murder in My Family, about the killing of his older brother, Alan, outside Houston in 1968, David Berg writes about going to see Joel and Ethan Coen’s 2007 film No Country for Old Men—not knowing that the film featured the actor Woody Harrelson in a supporting role.

The detail is curious for a number of reasons. It was Harrelson’s father, Charles Harrelson, who was tried and acquitted in the death of Alan Berg. David Berg said that for decades he was unable to watch movies or television shows featuring Woody Harrelson—the pain of seeing the son of the man he believes to be his brother’s killer was simply too much to bear.

But the reference to No Country for Old Men also resonates because the twisty, Texas-set tale of lawlessness and corruption that Berg recounts in Run, Brother, Run could have been conjured by a novelist like Cormac McCarthy, who wrote the book the film was based on.

Alan Berg was a carpet salesman working with his father in Houston when he was lured to a bar by a phone call from a mysterious woman promising sexual favors. Evidence suggests he was then kidnapped and killed. The killing may have been payback against the Bergs’ father, orchestrated by a former employee whom the elder Berg had been bad-mouthing in the community. There is also evidence that Alan Berg had significant gambling debts.

“You look at a movie like No Country for Old Men, and you see how something like my brother’s murder can happen,” Berg said in a recent interview. “The Javier Bardem character in that film is not far removed from Charles Harrelson.”

Berg believes the trial of Harrelson was beset by prosecutorial sloppiness and good-ol’-boy-style Southern injustice. The prosecutor, for instance, was unprepared when the defense began working to disqualify the testimony of a witness, Berg said. Meanwhile, the famed defense lawyer Percy Foreman brought in a group of witnesses to provide an alibi for Harrelson.

“If I were on that jury, I would have had to vote for acquittal, too,” said Berg, who has practiced law since 1968.

Harrelson was convicted of the 1968 murder of the grain dealer Sam Degelia Jr. in McAllen, and spent five years in prison. In 1979, he was sentenced to two consecutive life terms for the assassination of United States District Judge John H. Wood Jr. He died in prison in 2007.

Berg, 71, is well known in Houston for his political activism and his work on civil rights cases. For a time during the seventies and eighties, he was a defense lawyer in a number of murder trials, a painful irony he was well aware of.

“My responsibility was not to the family of the victims,” he said. “But I would look at them sometimes when I left the courtroom, and it was hard. It began to eat at me a bit.”

Berg decided to focus his practice solely on civil cases in the early nineties.

He started working on Run, Brother, Run, which is being published on Tuesday, in 2008, after decades of being unable to talk about the killing. With his younger sister, Linda, he pored over old police reports and legal files. He also tracked down and interviewed people involved in the case.

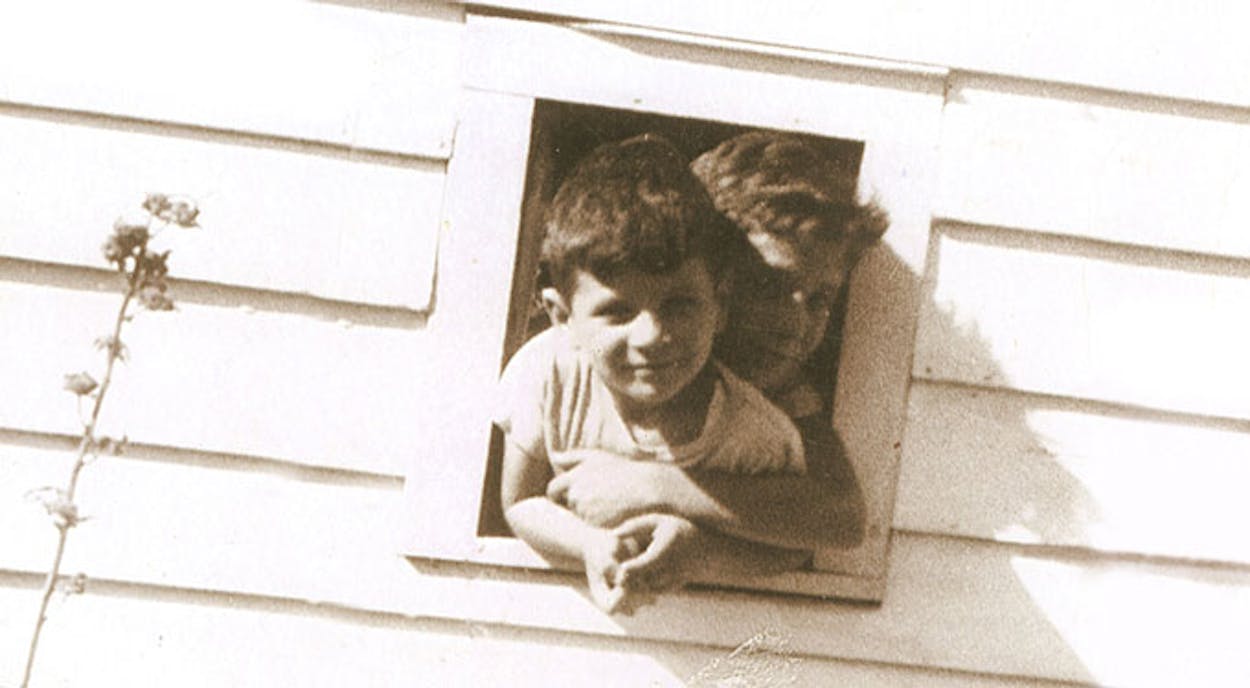

What is remarkable about the book, though, is Berg’s writing. He elegantly brings to life the rough-and-tumble boomtown that was sixties-era Houston, and conveys with unflinching force the emotional damage his brother’s death did to his family. His only previous book was titled The Trial Lawyer: What it Takes to Win.

“I think that David was writing from a deeper place than his lawyerly self,” said Colin Harrison, the editor in chief of Scribner, who acquired and edited Run, Brother, Run. “This book was coming out of his childhood and boyhood, and that made for writing that in no way resembles what you think of when you think of a lawyer writing a book.”

Berg, who peppers his conversation with references to literary memoirists like Mary Karr and Tobias Wolff, said he was not worried about falling into the traps usually associated with memoirs—the way such volumes can feel exploitative, or trample over the feelings of other family members who prefer that their stories remain private. (“If Alan thought I was exploiting his murder, he’d be thrilled,” Berg joked.)

Run, Brother, Run has brought his entire family closer, he said, and has allowed him for the first time to feel a measure of peace about his brother’s death.

“There was one night in particular, when I was writing the book and I received the very detailed statement of his murder,” he said. “My wife was out of town, and she called me that night, and I began to weep. I cried so hard that she thought someone had died.

“And I said, yes, someone had. It was the first and only time I had cried over my brother’s death.”

- More About:

- Books

- Woody Harrelson