On the day after Christmas in 1960, everything my two younger brothers and I owned was packed into a small cardboard box and put in the back of a white Chevy station wagon. Painted in black on the wagon’s front doors was a logo of a young boy wearing a cowboy hat and riding a bucking horse with another boy behind him holding on to the cowboy’s shirttail. “Cal Farley’s Boys Ranch” was printed across the top and below were the words “Amarillo, Texas.”

Looking out the car window, I watched the fast-falling snow and a small herd of antelope running across the rugged mesquite-covered prairie. My brothers and I grew excited, having seen the pictures on the Boys Ranch’s Christmas stamps. These stamps were mailed out twice a year to people across the country to solicit money for the ranch. One stamp showed a boy about eight years old wearing a blue cap and holding a puppy. The puppy was licking the boy’s face. Another showed two boys in cowboy hats riding horses through the snow. They both rode with their chins down, a Christmas tree tied behind the saddle on one of the horses. I longed to be the boy holding that puppy or the cowboy riding the horse with the Christmas tree tied to the back of his saddle.

While we were excited, Bobby, Karl, and I were also frightened. We were moving to this strange new place hundreds of miles from our mother, whom we’d been taken away from. My mother, whom we called “Honey,” was an alcoholic and suicidal. Providing for three children with no help is hard enough without an addiction—she just couldn’t handle it alone. She had moved us from one vacant house to another, so we had never attended the same school for an entire year. Our mother’s parents didn’t have the means to take care of us, and our other grandfather, on my father’s side, Karl “Doc” Sarpolis, didn’t want us. Nobody wanted my brothers and me except for Boys Ranch.

Paul Stuart was our driver. My brothers and I kept asking him questions about what Boys Ranch was like. After driving thirty-six miles northwest of Amarillo, Texas, which seemed to us like it was in the middle of nowhere, Paul Stuart pointed out to us a hill in the shape of a saddle. He told us that the hill was known as Saddleback Hill, which was on the edge of the Canadian River and served as a marker for the Native Americans. He told us it was a shallow bed of the river for the buffalo to cross and that the Native Americans would make arrowheads on top of the hill and wait for the buffalo. The western town of Tascosa sprung up alongside the river. Ever since I was a small boy, I loved Native American artifacts and stories of Buffalo Bill, Kit Carson, and Wild Bill Cody. In my mind, I couldn’t wait for a chance to look for arrowheads at the top of Saddleback Hill.

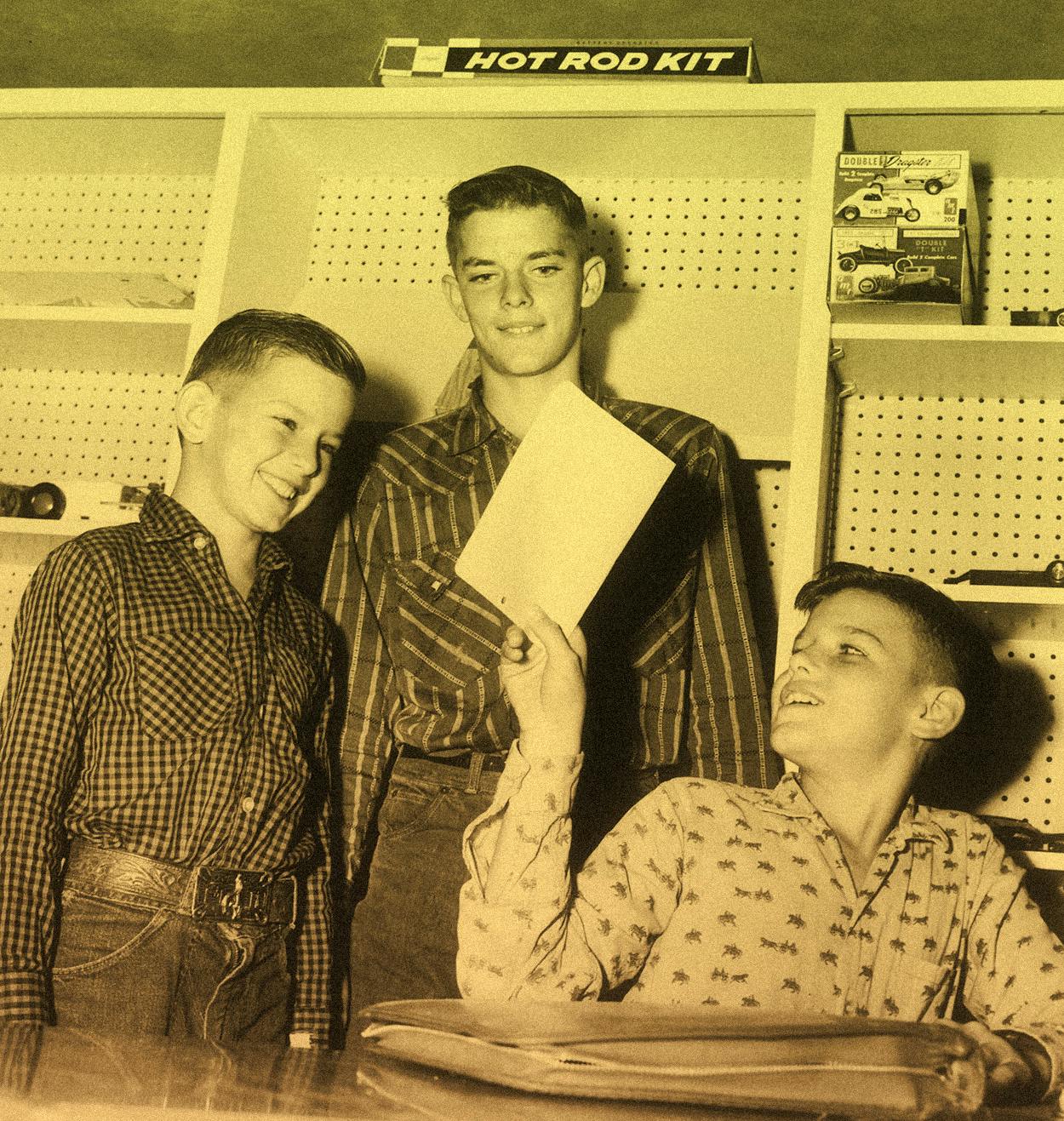

We entered the arched entrance to Cal Farley’s Boys Ranch. I noticed a beautiful white chapel, which Mr. Stuart explained had been moved to Boys Ranch from the air base in Dalhart. It was the focal point of the ranch. We parked in front of the Boys Center, an old white building with two large cottonwood trees in front. The Boys Center was the center of operations at the ranch. The post office, bank, and snack store were located in the Boys Center. This was also where visitors registered and where new residents were processed upon arrival. We were now new residents.

Three men in cowboy boots and jeans shook our hands and invited us to sit in the chairs along the wall. One of the men told us that we would do fine at the ranch if we followed the rules. He explained that we could go to Amarillo every third Saturday if we were not on “restriction.” If we were on restriction, we would be assigned extra chores after school and on weekends.

We could not carry cash, he said. If we wanted to buy anything, we’d write a check from a Boys Ranch bank account. All checks had to be initialed by our dorm parents. We would each be provided new clothes. After that we would buy our own clothes from a monthly allowance, which was based on each boy’s age. Church and Sunday school attendance was required. Most importantly, each boy was required to report at every roll call, which was called “muster,” several times a day. We were to follow all orders from our dorm parents or be punished. If we did not earn passing grades in school, we would be placed on restriction.

“Finally,” he said with a smile, “the older boys will help you adjust and learn the rules.”

Then a man with a limp came in, also wearing a cowboy hat and cowboy boots. He was about twenty-five years old and a little overweight. He had a big smile, and somehow he reminded me of Santa Claus.

He stuck out his hand and said, “I’m Gene Peggram, your dorm parent.” He shook our hands and picked up our cardboard box. “I’ll show you your dormitory.” We followed him to his pickup, and he put our box in the back as Bobby, Karl, and I jumped into the front seat. As we drove away from the headquarters, Mr. Peggram said our dorm was named “Jim Hill,” after a man who had donated money to build it. He added that thirty-six boys were living in Jim Hill.

We drove up a small hill and approached the dorm, built with Colorado red stone. A porch stretched across the front. Apartments for the dorm parents anchored each end of the building. Between them was the living room, or “big room,” furnished with couches, a coffee table, and a TV set. Full-time dorm parents lived in one apartment, while alternate dorm parents, usually schoolteachers, lived in the other.

Jim Hill was one of a group of four dorm buildings known as the “Hilltop dorms,” while the dorms on the other side of the dining hall and around a big hill were known as the “Valley dorms.” We parked in front of Jim Hill, got our box out of the pickup, and went inside.

By the door were two cardboard boxes, one filled with oranges and the other with bananas. Located at each end of the big room was a door that led to a long hall that stretched from room 1 to room 6. Each room had three bunk beds and three closets. Located at each end of the hall was a bathroom with four sinks, four toilets, and four showers. Thirty-six boys shared a bathroom at each end of the hall.

Mr. Peggram explained that each room was numbered. Bobby and I would live in room 2, while Karl would live in another dorm for younger boys. It hadn’t occurred to us that we could be separated. I asked Mr. Peggram why Karl couldn’t live with us. He said Karl would move to a “big boys” dorm the following year, when he was older. He must have realized how upset this arrangement made us because he relented, saying Karl could stay with Bobby and me for the next five days until all the boys returned from Christmas holiday.

In our room, there was a couch and a desk along with the three bunk beds. The mattresses on the bunk beds were about an inch thick. Each closet was about five feet by four feet. Mr. Peggram said we would share our closet with another boy. He opened one closet door, and I saw that the clothes that took up half of the closet were perfectly folded—the other half of the closet was empty. There were a few family photographs on the first shelf and a few pair of pants and T-shirts on the other two shelves. Mr. Peggram told me that would be my closet and I would be sharing it with a boy named Pete Flack.

Mr. Peggram checked his watch and said it was almost time for dinner and that he’d give us a ride to the dining hall. The dining hall was one large room with about fifty round tables, eight chairs to each table. Hundreds of coat hooks lined the walls. At the center of the front wall was a stage. The kitchen was on one side of the stage, and the dishwashing room was on the other. Mr. Peggram showed us the cafeteria line, where we filled our plates with food, then we followed him to a table where four boys were already seated. They also lived in Jim Hill dorm. Of all thirty-six boys in Jim Hill, these four were the only ones who hadn’t gone home for Christmas. As we ate, the four boys introduced themselves and answered the many questions we asked.

As we walked back toward the dorm after dinner, Mr. Peggram pulled up in the same station wagon we rode to Boys Ranch in and asked if we wanted to go bowling or see a movie in Amarillo. All seven of us scrambled in, and Mr. Peggram drove us the thirty-six miles to the bowling alley in Amarillo. We bowled for hours and then slept in the station wagon on the way back. We had a great first day, and I thought this was the beginning of something very special in our lives. As I dozed off to sleep, I could see myself riding a horse with a new pair of boots and a cowboy hat.

The next morning after breakfast, Mr. Peggram took us to a country store to get our new clothes. All I could think about was a pair of cowboy boots and a cowboy hat. The country store was a small white building behind the dining hall. Our “new clothes” were khaki army fatigues that had been donated from the air base in Amarillo. They were too big and didn’t fit well, but they were free. Each of us was given two pairs of pants and two shirts. We also got one pair of dress slacks, a dress shirt, and dress shoes to wear only to church or trips to Amarillo. Then we were fitted with army brogans: brown high-top shoes with leather laces. We were each issued four pairs of socks and underwear and two T-shirts.

When I asked Mr. Peggram when we’d get a cowboy hat and a pair of cowboy boots, he chuckled and answered, “When you have the money to buy them.”

He labeled all our clothes in red ink with our own laundry numbers, explaining that this was to identify our clothes from the other 350 boys at the ranch when the clothes came back from the laundry. My number was JH83. Bobby and Karl each had their own numbers.

I asked Mr. Peggram when I would get to ride a horse. He laughed and said that later that afternoon, I could go to the horse barn and wait in line to ride a horse. That was all I could think about the entire day. I wanted to ride that horse and pretend I was a cowboy. At 1:00 p.m., I hurried down a dirt road flanked by cottonwood trees to a cinder-block building. There were horse stalls on one side and dairy cow pens on the other side. Standing in line behind several boys, I waited for my turn to pick a horse to ride. A clipboard had a list of the horses’ names with a blank line next to each one. I had to select a horse and sign my name on the line. Turning to the boy behind me, I asked which horse to pick. He said to choose the horse named Sleepy because he was slow. Sleepy was the horse they used to teach boys to ride. Another boy helped me pick out a bridle and saddle, showing me how to strap it on the horse. I mounted Sleepy, rode for more than an hour, and fell in love.

I returned to my dorm that afternoon, fell into my bunk bed, and thought about how wonderful it was to be at Boys Ranch. I had a bed, new clothes, and fresh fruit by the door. We went bowling, and I got to ride a horse for the first time. Life could not be any better. Although I missed my mother, Boys Ranch was perfect for my brothers and me. I fell to sleep wondering if my mother was OK. I was twelve years old and had gone to sleep many times worrying about my mother. I had seen her drinking get worse each night for years. She had become very depressed and had tried several times to take her own life. She was my mother, and to me she was the best mother in the world. I knew deep inside she was struggling and that her sons were her life—it must have been so painful knowing she had to give us up and that she could not provide for us. That must have made her feel like a complete failure.

Two days later our lives at Boys Ranch changed when more than two hundred boys returned to the ranch. The dorm parents searched everyone’s luggage and clothes, looking for cigarettes, cash, and other contraband.

Before dinner, some boys started walking throughout the dorm yelling, “Muster!” I reported immediately to the living room. Mr. Peggram stood in the center of the big room as all the boys hurried to grab a seat on the couches along the walls.

As Mr. Peggram read the names of each boy in the dorm in alphabetical order, each boy responded, “Here, sir!” After he read all the names, he asked Bobby and me to stand. He introduced us to the group, and the boys clapped to make us feel welcome. We were referred to as the “new boys,” a nickname for boys who were new to the ranch.

After muster we walked to the dining hall, where we were assigned permanent seats at a table. Bobby’s table was next to mine, and we searched for Karl. He had just moved into the dorm for younger boys and knew no one. At least Bobby and I had each other. When I spotted my little brother, I hurried to his table to ask how he was doing. A man yelled at me, ordering me back to my seat. Karl began to cry. That man told Karl to shut up and sit down. As I walked back to my chair, I began to realize we were now living in a different Boys Ranch.

- More About:

- Books