This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

I knew I couldn’t be a Pi Phi. I went to the wrong camp,” the sophisticated Houston coed explained as we walked out of the Junior Ball Room of the University of Texas Student Union with respectable sorority bids in hand. The 1962 rush week “pig squealing” was over. For me, a small-town girl, it had been a week of unconscious blunders, naive assumptions, unwarranted overconfidence, and too much punch. I was forewarned that I would need a jingly (preferably gold) charm bracelet to wear to the Pi Beta Phi rush parties in order to participate in the sisterly singing of “Ring Ching, Pi Beta Phi.” The bracelet’s symbols of high school accomplishments momentarily buoyed flagging small talk throughout the week; but there were status symbols that had not made their way to my rural province in East Texas. I had never been particularly concerned with Sakowitz and Neiman-Marcus labels or Villager oxford cloth blouses. Pappagalio dress shoes held no majority in my closet. How was I to know about camp?

Certainly no one had asked me about the two weeks I had spent at Girl Scout Camp High Point in Mena, Arkansas, a healthy preadolescent experience that bore no resemblance to the camp stories I would hear about during my four years at The University of Texas. I gradually became aware that the camp one went to made a remarkable difference in all sorts of social endeavors, both in college and in the years that followed it.

My first visit to the Texas Hill Country around Kerrville convinced me that it is a camper’s paradise. The cool, clear waters of the Guadalupe River are irresistible, and I waded in before reaching the first camp on my tour. The hills themselves are part of camp life, since they provide a natural setting for secret “tribal” meetings. After you’ve heard the echoes bounce off Joy Bluff at Camp Stewart, you don’t wonder that a Great Spirit could light the bonfire. With my feet in the Guadalupe, I lost a good bit of my skepticism about Hill Country camps. As one former camper put it, “All I know is, I thought about things on the banks of the Guadalupe that just wouldn’t have occurred to me if I’d stayed in Dallas.”

In a week I visited seven camps in the Kerrville-Hunt vicinity before going on to Inks Lake to see camps Longhorn and Champion. I wanted to explore the mystique of the legendary girls’ camps like Waldemar and Mystic. What was it about them that inspired such loyalty? Why would a college coed wear her diamond camp ring well into her junior year? Was it true that debutante bows were a part of the calisthenic program at Waldemar? Why did wives at lawyers’ conventions or medical meetings greet each other with “Kiowa?” “No, Tonkawa”? Or why would a 40-year-old woman squint through binoculars across the Cotton Bowl and nudge her husband, “See that blonde five rows up in the first deck? She was in War Canoe with me at Waldemar.” What did these camps offer that would make a Texas daddy who had invested more than $12,000 in 25 cumulative years of summer camp for three daughters say, “It’s a bargain.”

“I overheard a counselor say, ‘We’ve got to get them crying tonight, so they’ll sign up for next year.’ ”

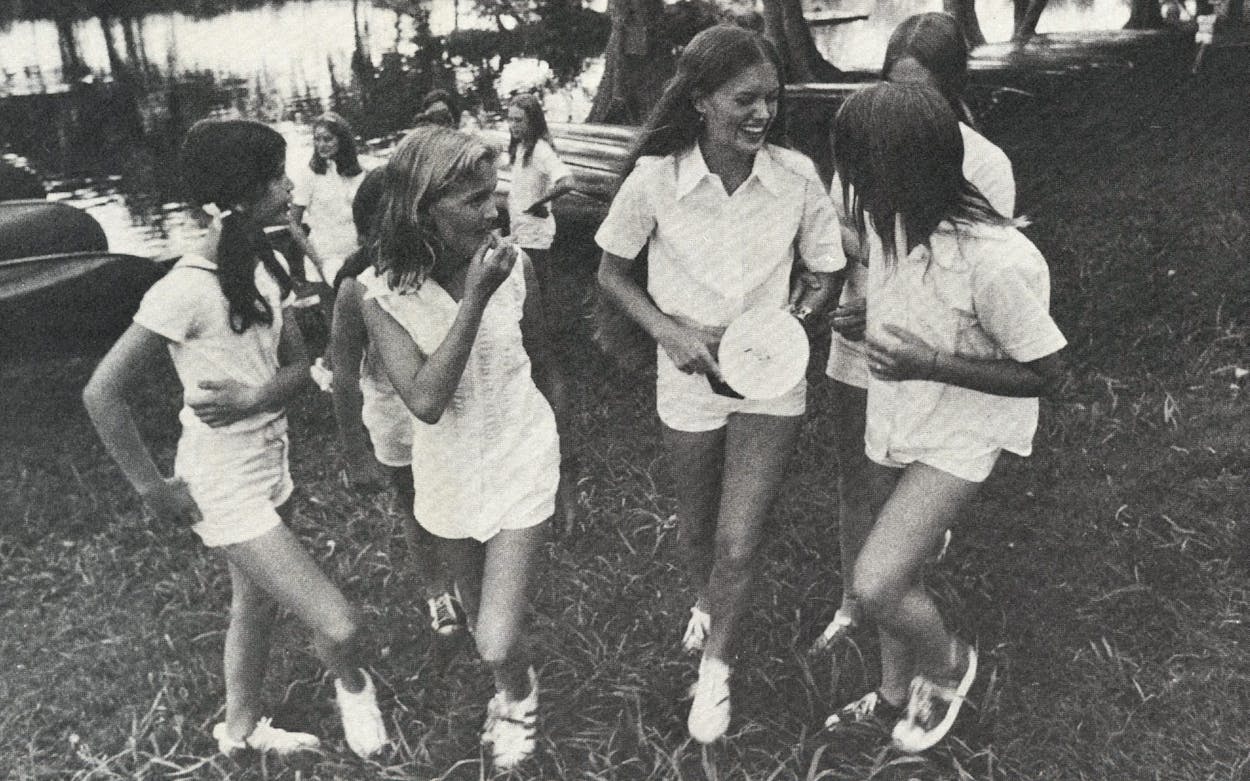

At fees of $465 to $650 per session (usually four to five weeks), all the private girls’ camps along the Guadalupe offer a standard curriculum—swimming, canoeing, archery, riflery, horseback riding, tennis, crafts, tumbling, and dance. Some offer a great deal more. I couldn’t help wondering if cheerleading appears as a regular activity in camps in Wisconsin or upstate New York as it does in Texas.

Girls’ camps are emotional places. Take little girls away from boys for four weeks and they fall in love with each other. They adore secret clubs and tribes, where they hug and cry a lot and sing tearful, terrible corruptions of 1930s love songs or Broadway musicals. It’s a confusing blend of Protestant Christianity and pantheism, with the word “love” used so liberally that a nine-year-old couldn’t be sure whether she was crying because she loved Jesus, the Kickapoos, the tribal True Blue, or her counselor.

During my camp sojourn, I kept experiencing deja vu. I knew it couldn’t be my old Girl Scout days, but it wasn’t until I overheard a counselor say, “We’ve got to get them to crying tonight, so they’ll sign up for next year,” that I knew. It wasn’t camp; it was the sorority house during rush week, with the songs calculated to bring tears, the embraces, the rituals, and the ubiquitous Rodgers and Hammerstein scores.

One of my contemporaries, a Rice graduate, has always been puzzled and slightly amused by a University of Texas phenomenon. “Texas graduates,” he says, “do not view their four years in Austin as a terminal experience.” He theorizes that it is only a small part of a much larger picture, a place where paths begin to cross from all over the state in ways that will somehow affect the rest of their lives. I could hardly wait to tell him that though the bonding process is galvanized at UT, it does not always begin there. The words of the Houston coed came back, “I went to the wrong camp.” I had unwittingly stumbled on one of the earlier threads in the continuum of Texas society.

A remarkably beautiful and healthy fifteen-year-old girl stands on the banks of the Guadalupe to give her inspirational vespers talk. She begins profoundly, “Two roads diverged in a yellow wood.” Poor Frost. Would he enjoy the irony of his “The Road Not Taken” read on this hallowed camp ground? Camp, after all, is a decidedly decisionless place to be. As one ingenuous child said, “It’s so easy to be good at camp.” The other irony, of course, is that for most of these little girls the road is already chosen. It goes from Hill Country camp to private school, or at least to an affluent suburban high school, to what Texans regard as Eastern girls’ schools: Mary Baldwin, Sweet Briar, Mount Vernon, Hollins, Randolph Macon, or any of those institutions which offer the “Texas Plan.” This plan allows girls to have one or perhaps two years out of state before returning to THE University where they can live at Miss Hardin’s (Hardin House it’s called now), acquire the necessary sorority credentials, marry lawyers, doctors, or inherited wealth, have two to four lovely, wholesome children, run carpools, dance a few years in the Junior League follies or work in the Thrift Shop, and “knowing how road leads on to road,” put their children on the appropriate waiting lists.

Counterparts of these Hill Country camps are dying out in the East. Spiraling expense, complaints from the kids that camp is boring, and competition from shorter term, specialized camps have taken their toll. Wilderness camps are so popular now that they can often charge more and offer less.

But the Hill Country camps don’t seem to be suffering. To be sure, they have problems. Texas camps are currently fighting federal safety regulation, even though the ones I visited could probably pass the most stringent of safety inspections. I suspect the directors’ real fear is that any federal interference will not only increase paper work, and hence costs, but also might threaten their prerogative to decide who attends.

“ ‘Get to know the boys in your cabin, Son,’ one Camp Stewart father admonished. ‘Lamar Hunt was in my cabin and I didn’t give a damn. Now I just wish he knew my name.’ ”

Kids themselves have changed in recent years and pose some challenges. Janis Joplin probably never envisioned, “Oh, Lord, Won’t You Buy Me a Mercedes Benz” as a song at Camp Kickapoo in Kerrville. Baseball teams at Camp Stewart have names like the Margaritas and the Harvey Wallbangers. Most directors admitted that their campers are more worldly wise and better trained athletically than in years past, but certainly no more mature. Nurses said they were stocking as much Maalox as Mercurochrome since many kids arrive with potential ulcers. They also said that more children are on prescribed medication than ever before.

No director would admit that drugs had ever been a problem at his camp, but all were extremely vigilant. A child at Heart o’ the Hills was seen hiding a bag of white powder under her pillow, which a counselor quickly took to the director. Analysis at the Kerr County sheriff’s office revealed that the bag contained ascorbic acid, a bittersweet candy substance. Si Ragsdale says that some of his campers wrote home with fictitious claims that they had discovered cannabis growing on Stewart’s property and implied that Mr. Ragsdale was raising a bumper crop. Kids are more likely to challenge authority these days. “Why should I have to ride horses? I hate horses.”

Some camps are obviously bending with the times. Rio Vista for boys, established in 1921, seems to pay lip service to its Indian tribe traditions while actually becoming more and more a specialty sports camp. Its eight magnificent laykold tennis courts reveal the principal interest of Jack McBride, Rio Vista’s director and stockholder, who sees the possibilities of another Lakeway-type resort in the Hill Country. Increasing budgets and a dearth of “good help” are inescapable problems. The cost of sending a child to Mystic increased from $575 last summer to $635 this year. Cafeteria food service has replaced family-style meals in all the camps except Waldemar, Kickapoo, Mystic, and Stewart.

In spite of problems and costs, these camps still have waiting lists. Most of the directors are talented salesmen, and their programs still please Texans. And camp has always been a safe place to park the kids while Mom and Dad were in Europe. But most of the parents I talked with suggested that they weren’t so eager to get rid of the kids as they were to go to camp with them. A former Waldemar Ideal Girl whose daughter will soon be a camper recalled how safe and secure she felt at Waldemar. “I’ll never forget the time some boys on motorcycles roared into our camp. I was near the kitchen and saw the cook run out brandishing his butcher knife after the hoodlums. I remember thinking, ‘Gosh, they really must love us.’ ” These parents have terrific nostalgia for a place that is seemingly unchanged, for a time in their lives when life was uncomplicated by adult responsibility.

Then there are the social implications. These camps are the closest to boarding schools most Texans will ever get, and they perform the similar function of introducing affluent children to one another. “Get to know the boys in your cabin, Son,” one Camp Stewart father admonished. “Lamar Hunt was in my cabin and I didn’t give a damn. Now I just wish he knew my name.”

Heart o’ the Hills, its roots in Texas legend, has less social pretensions than most of the other camps I visited. Built as a lodge by Dr. E. J. Stewart, who was then the owner of camps Stewart for boys and Mystic for girls, Heart o’ the Hills was intended to house the parents who came to Hunt for camp ceremonies. Arriving in the area without a hotel reservation, Dallas millionaire Colonel D. H. “Dry Hole” Byrd reportedly demanded a room at Heart o’ the Hills. The clerk assured him that no rooms were available, so, in fine Texas fashion, Byrd turned to his companion Kenneth Jones, a maintenance man from Camp Mystic, and said, “Kenneth, if I bought this place, would you run it for me? I need a place to stay.” Jones agreed, and Byrd told the clerk, “We’ll take it.”

Jones and his wife turned the lodge into a camp in 1953. Its acreage is decidedly limited as Hill Country camps go, but the beautiful Guadalupe waterfront is accessible by tunnel under the highway, and steep hills rise behind the original lodge to provide the secret tribal grounds for the Heart tribes—Pawnee and Shawnee. Although it has long since been under different ownership, the camp’s highest achievement award is still called Jo Jones Girl, a memorial to Jones’ daughter who was killed in a car accident.

Heart o’ the Hills, now owned by Carl and Diane Hawkins, is the smallest camp I visited. It accepts 125 girls, aged six through sixteen. The Hawkins see the small size as a distinct advantage since it offers each camper a better chance to excel, as well as an opportunity to ride horses every day. Larger camps offer horseback riding only on alternate days.

The Hawkins are hard-working people with extensive professional experience. Hawkins loves what he does and has a genuine concern and sympathetic ear for every girl in the camp. The program is full, but relaxed, with particular emphasis on the kids having a good time and making friends, rather than perfecting the final show for parents. The finale was in fact terrible—the craft display had the usual monstrosities: painted rocks, lap boards, and decoupaged plaques—but the little girls enjoyed it. Tribal competition is fierce between the Pawnees and the Shawnees throughout the session, but is lessened somewhat by the joining of the tribes to form one Heart Tribe at the closing.

Additional hands to do the heavy or tedious camp work are scarce, expensive, and frequently unreliable, so there are few jobs that Carl and Diane Hawkins cannot handle, be it mowing grass, slinging hash in the cafeteria-style dining room, or counting up camp store deposits. Knowing who’s who in Texas is simply not a part of the Hawkins’ experience, although their camp obviously draws from affluent families around the state and from northern Mexico. I returned from a neighboring camp one afternoon and mentioned to Hawkins that I’d seen one of Ross Perot’s children. “Is that someone I should know?” Hawkins asked. Impossible? Not when you understand the news vacuum that exists in Hunt. Television and radio reception are so poor and the Kerrville Mountain Sun so completely local in coverage that it took me three days to learn that Fred Carrasco was dead in Huntsville. But it isn’t just the inaccessibility of news that insulates you in Hunt. Camp is a cosmos unto itself. Nixon made his resignation speech on the closing day of one of the camp sessions. I was so involved in camp life by that time that I experienced some irritation that parents would delay the Memorial Vespers by refusing to leave their portable radios. Who cared about the American presidency; I wanted to know who had won the Jo Jones award.

I learned a code at Waldemar that’s almost a burden at times,” the young woman told me. “Eight years at Waldemar taught me never to settle for anything less than the best in everything—pure quality—no veneer. I learned to do things thoroughly and to expect the same from others.” She had been a camper at Waldemar sixteen years ago and, like an amazing number of women I talked with in Dallas, she felt Waldemar was one of the great moral influences in her life.

For sheer natural beauty, Waldemar’s 1200 acres along the North Fork of the Guadalupe in Hunt are unparalleled in the Hill Country. Architect Harvey P. Smith, who also restored the Spanish Governor’s Palace and several missions in San Antonio, insisted that no trees be cut, and designed native stone structures that seem to grow out of the hillside. Massive trees grow right through the roofs of several cabins. The masonry executed by German immigrant craftsman Ferdinand Rehberger in 1931 is matchless. The perfectly tended plantings suggest that the grounds keepers bear the burden of the Waldemar code, too. The Kampongs (cabins) are not carpeted or air-conditioned as detractors had tried to tell me, but they have a certain Spartan beauty: bunks are dark-stained oak, floors are red Mexican tile, and several cabins have fireplaces. The walls bear no names, carved initials, or tribal slogans. Since Kampongs are inspected twice a day, bedsheets had “hospital corners” and trunks were immaculate. The bathrooms, cleaned by maids, were sparkling.

August 1974 was not a good time to judge camp food. Rampant inflation could not have been foreseen when budgets were drawn up in the spring, but Waldemar was typically unperturbed by it all. None of the mysterious pizza, tamale, noodle, and Frito concoctions I had seen in other camps ever appeared in the polished dining room, where white-coated black waiters attended the tables. The food is legendary: “I ate my first soufflé at Waldemar,” a friend recalled. There are few packaged mixes, and the aesthetic manner in which the food is served is deemed as important as nutrition.

But it is not only the setting and the food that place Waldemar apart from other Texas camps. Some say it’s the Waldemar spirit, the immutable traditions, the social clout, and the intense loyalty it breeds; others believe it just may be Doris Johnson herself, owner and director of Waldemar and niece of its founder, Miss Ora Johnson. One friend admitted that as a nine-year-old, she had believed that perhaps Miss Ora’s ghost floated around the camp site at night.

“Waldemar is the only experience from my own childhood that I can offer unchanged to my daughter,” one mother explained, as I needled her about having enrolled her newborn daughter for Waldemar in 1983. Tradition is a big drawing card for any Texas institution, and Texas traditions require only 30 or 40 years to develop. The Hill Country camps, especially Waldemar, have made the most of it. The tribal rituals, the War Canoe picnic, and even a special Victorian vocabulary remain the same at Waldemar. Snack time is called “Nourishment,” and who could forget Miss Roe, former calisthenics teacher, calling, “Boozerings up, whosits in, squeeze those legs together.” Waldemar standards are traditionally rigid. Right and wrong are so clearly defined at camp that seemingly slight infractions may require a full confession before the entire tribe.

Waldemar offers the standard camp athletic activities, but with strong emphasis on perfecting form. Those who have attended camp long enough to participate in War Canoe, an exhausting activity requiring strength and impressive precision, can undoubtedly identify with the girl who said, “Every year after I got home from camp, I would turn my bare back to the mirror, lift my arms to a ballroom dancing position and watch with tears in my eyes as the muscles rippled across my back like Charles Atlas’.” Even my most cynical friends became a little misty-eyed about Waldemar’s tradition of traditions, the Ideal Girl Ceremony. The most loyal return year after year, well past their college days, to participate. The Ideal Girl is elected by the entire camp and staff at the end of a session, and her virtues are extolled in a candlelight ceremony that has not changed since the camp began. Once she is named, she is taken down the Guadalupe in a white canoe paddled only by former Ideal Girls while the entire camp sings, in choked voices, to “the spirit of Camp Waldemar.”

Waldemar accepts girls aged nine to sixteen and has a capacity of 306. Present preenrollment applications will fill the camp through 1983. Grandmothers have been known to secretly enroll granddaughters whose mothers were still rebelling against their own upbringing. “Sally will thank me when little Sarah is nine years old.” Although there is really no debutante bow practice at Waldemar, the social implications of going there are undeniable. Even the least enthusiastic campers admitted, “I wouldn’t have thought of going through rush at Texas without my Waldemar ring.” One ex-camper was amazed to hear a friend who had attended another camp admit that she had participated in skits satirizing Waldemar. “I was a little sad to think that they were so aware of us,” the Waldemar graduate said. “We never even thought about them.”

Indeed, Waldemar has experienced no competition from other camps along the Guadalupe, although “Nakanawa, in Tennessee, once took a lot of our Dallas girls,” Doris Johnson conceded. Doris—she is known by her first name to all Waldemar campers—is the embodiment of the Waldemar spirit, high standards, and organization. Always clad in white, this slightly imperious doyenne of the Hill Country camps lives year-round in Rippling Waters, her home on the Waldemar grounds. She has been associated with the camp since 1928.

Doris maintained a certain aloofness throughout our conversation; however, as we strolled the grounds, it was apparent that she never forgets the name or face of any camper. When I mentioned my own contemporaries who had gone to Waldemar, she recalled not only their married names, but also the names of their children. As I sat in her office looking at the massive wooden card catalog that records the pertinent information on every past camper, I couldn’t help wondering how many of them regarded Waldemar as the last bastion of civilization. Perusing a Record Card, I noted that table manners are graded on a scale of 1 to 10. “Don’t sixteen-year-old girls find this a little silly?” I naively asked. “It’s more important than ever now; families eat on TV trays,” Doris replied with ill-concealed disgust. I knew that Waldemar attracted girls from New Orleans and Little Rock particularly during the second session, but I saw no evidence of the Mexican aristocracy from Monterrey, Piedras Negras, or Mexico City that I had frequently encountered in the other Hill Country camps. “We tried that once,” Doris explained, “but we saw no need to continue. Their English was poor and, since most of them are raised by servants, they have terrible manners and are much too spoiled for camp life.”

“What about notable or famous women who have attended Waldemar?” I asked. An icy hesitation suggested that I had trespassed. She replied with inoffensive though patronizing protectiveness, “No, I can’t think of anyone who’s made a name for herself.”

What will become of Waldemar when Doris is gone? She is seventyish, and there is no clear line of succession. Wealthy parents and former campers, her loyal subjects, stand nervously in the wings awaiting her instruction.

If I asked a Mystic camper about the traditions she learned at camp, she would tell me about the tribes Kiowa and Tonkawa and the training rules—unchanged since 1928—that prohibit bare feet, Coca-Cola, candy, and talking at rest hour. She would tell about living in cabins called Chatter Box or Angels’ Attic or Hangover where her mother’s name might be found carved in the rafters, or about tribal serenades, or winning Best Posture.

“The Spirit of Camp Mystic is love,” says Inez Harrison, the camp’s director. “And that spirit pervades our whole camp. Mystic girls learn to love God first, others second, and themselves last.” Before the day was over, however, I would know that Inez Harrison is no naive grandmother and that beneath the almost cloying sweetness there is a strong intelligent organizer with a sound visceral sense of what these little girls need and what their parents expect.

Mystic has long been a favorite of the Texas political aristocracy. Texas Governors Dan Moody, Price Daniel, and John Connally have all sent daughters there. Lyndon Johnson’s daughters were also Mystic campers. Luci unexpectedly took refuge here after the 1960 Democratic convention. Even now, Luci acknowledges Inez and Frank Harrison as her much beloved summertime parents.

Inez sees Mystic as a retreat. “The world demands too much sophistication of these little girls,” she says. Outside that gate these same fourteen-year-olds might talk knowledgeably of birth control or the merits of The Last Picture Show, but once inside, they are little girls screaming their hearts out for the Tonkawas. When they return to the real world, they might be a little embarrassed at this display of emotion, but for five weeks they can live without affectation.

Campers come from all over the state. Mystic also welcomes the children of Mexico’s affluent families, but Inez admits that language and cultural barriers are not always so smoothly crossed. Imagine the trauma of a little Mexican girl being introduced for the first time to that relic of American pre-Freudian toilet training, the “Health and Happiness Chart,” on which each child records her tooth brushing and daily bowel movements. One Mexican camper went for days without brushing her hair. The counselor hated to reprimand her, but by week’s end, after swimming and riding horses, the child’s hair was hopelessly matted. An older cousin was summoned to ask why she hadn’t brushed her hair. “I don’t know how,” the eight-year-old replied in Spanish. “My ladies have always done it.”

Escorted by two counselors, I toured the camp grounds. Mystic’s 650 acres on the South Fork of the Guadalupe are remarkably beautiful, but unmistakably camp. The cabins, although perched aesthetically on a hillside, are still no-nonsense frame or Central Texas stone with concrete floors. Indoor plumbing was added in 1939. A brief trail ride within the camp acreage took me through a clear creek and up to Natural Fountains, a curious basin-shaped stalagmite formation under a cliff, with natural springs bubbling up in it.

While observing the Mystic waterfront activities, I was startled to see a white Cadillac driven by what I took to be somebody’s grandmother come barreling down to the water’s edge. “Oh, that’s just Ag,” the counselors assured me. Agnes Stacey, an owner of Mystic and a camp personality since 1937, climbed out of her car and headed for the water. After a disciplined number of laps to and from the raft in the middle of the river, she climbed out, blue-rinsed hairdo intact. The counselors introduced me, and Ag said, “You know I used to swim every day to the dam and back, but now they won’t let me go alone, and these counselors can’t keep up with me. You be at my house in about fifteen minutes. It doesn’t take me as long to get into my girdle as you might think.”

Born in Dallas in 1887 on a farm where the Cotton Bowl now stands, Agnes Stacey (then Doran) turned down a Dallas debut to attend The University of Texas, against her father’s wishes. There she appeared on Cactus beauty pages, pledged Kappa Kappa Gamma, received a T Association letter in swimming, maintained a creditable academic record, and met Bill Stacey, a UT tennis champion. Her postgraduate days included graduate work at Wellesley, teaching school in France, and Junior League work in Austin. She and Bill took over Camp Mystic in 1937, possibly the worst time in American history to sell people on the importance of a private camp for girls.

It became apparent during my brief stay that Ag Stacey’s stamina and her link with the Texas aristocracy are still a part of Mystic’s continuing success story. The actual directing of the camp has been delegated to Inez and Frank Harrison, but this doughty octogenarian has not completely retired. She is still likely to appear in unexpected places doing unexpected things. Campers requesting a song from Ag after dinner may be awed to see her climb up on the piano and belt out, “Oh My Man, I Love Him So.”

The camp calendar of activities is largely unchanged since Ag organized it years ago. Mystic offers twenty activities, of which campers select eight. The tribal competition in tennis, swimming, canoeing, and baseball produces amazing athletic prowess among the girls, but their energy is also channeled with equal zeal into cheerleading and twirling activities.

No one leaves Mystic without some sense of personal accomplishment. Even the klutziest kid can stand up straight for a week in order to win Best Posture or get fork to mouth efficiently enough to be named Best Manners. At Final Campfire, no less than 30 awards are bestowed, but there is no Miss Mystic. The honor that most little girls seem to seek is to return as a counselor. Former campers have told me that they were always aware of their counselor’s sorority and that considerable preliminary rushing took place at camp. On learning my affiliation, Ag almost upset the mashed potatoes to slip me the Kappa grip across the lunch table.

Most of these private camps have recruiting parties at country clubs in the major cities. I attended a Coke party for Camp Arrowhead in February and couldn’t help noting the disparity between the movies of sunny Arrowhead flickering on the screen before the well-groomed audience of mothers and daughters and the camp I had seen on a rainy day the previous summer.

Arrowhead is noticeably more rustic than Waldemar or Mystic and even a little bleak on a rainy day, with muddy paths linking cabins that appear unimproved since the Thirties. The heart of the camp is on very flat terrain with only the clear Guadalupe and its cypress trees beautifying the site. When I saw separate bathhouses between cabins, I thought to myself, “Now this is camp. These little girls don’t mind roughing it.” The cafeteria-style dining hall, called the Filling Station, suggested that eating was purely for nourishment. “Good manners are encouraged,” one mother told me, “but Arrowhead doesn’t try to be a finishing school. It’s just a place to have fun.” The only hint of social pretension I saw at Arrowhead was the naming of the age divisions: Debs, Junior Debs, and Sub-Debs.

Arrowhead is by no means, however, an ugly stepsister of the other Hill Country camps. It offers similar, well-taught activities, equally adequate sports facilities, and it inspires great loyalty among wealthy alumnae across the state. Mothers who had gone to Arrowhead could hardly wait to start packing their daughters’ trunks. “It hasn’t changed a bit since I was there,” one mother said. I could feel mothers around me thrill to Garner Bartell, camp director and owner, saying, “We’re just as square as we’ve always been.” Mrs. Bartell’s family has been associated with the camp since its founding in 1934.

Arrowhead’s tribes, the Kickapoos and the Pawnees, promote teamwork, leadership, and competition. A second-generation camper may choose to be in her mother’s tribe, while others are assigned arbitrarily. Other than a few individual certificates and ribbons earned by campers, no awards are given at the Final Campfire. Mrs. Bartell feels that too many awards detract from the lifelong rewards of good camping experiences.

There are private boys’ camps in the Hill Country, too. Stewart is widely acknowledged to be the male counterpart of Waldemar and Mystic. Silas B. Ragsdale, Jr., exchanged his coat and tie for shorts and tee shirt when he left the Denton Chamber of Commerce in 1967 to become the owner and director of the socially prestigious camp, but he brought his super-salesmanship abilities with him. Touring Stewart’s 500 acres with Si in the camp’s orange and white Ford Bronco, I learned a good bit about boys, Stewart’s traditions, its problems, and its successes.

As we rode along, I could see that Stewart’s site doesn’t require much selling. The Guadalupe branches and bends to form four separate water areas—Blue Hole for fishermen; Bathtub, an area of shallow white-water rapids for nonswimmers; a Junior Pool with a Tarzan rope for average swimmers; and a Senior Pool for water skiing and canoeing. Joy Bluff rises above the Senior Pool and provides spooky echoes for nighttime bonfires. Younger campers’ stone and frame cabins line the road that follows the athletic playing fields. Older campers stay across the river in Senior Camp.

Si’s commentary made me well aware of the special problems that plague a boys’ camp. He readily admitted that little boys are destructive, careless, and, most of the time, dirty. They will go to great lengths to avoid taking a shower and can mysteriously break four screens in their cabin during rest hour. “Now, that’s what I’m talking about,” he said, pointing to the broken window in the back of the camp station wagon. “That got busted during the dance with Waldemar, and no one is even sure how it happened.”

Boys do not seem to form the emotional attachment to camp that little girls do, but that doesn’t mean that camps like Stewart are devoid of tradition. Si stopped the Bronco long enough for me to meet “Mr. Lip,” Stewart’s favorite personality and link with the past. For 35 summers, Travis Lipscomb has served the camp in some capacity. Now, as head counselor, he remembers the good old days when “Uncle Bill” James directed Stewart. The place was much smaller then, and campers much less sophisticated. “With Uncle Bill, the boys just did a lot of hiking and sleeping out,” he recalls, “but now they require every day to be filled with planned activity.”

Our next stop was the dining hall. Like Waldemar, Stewart’s bread is homemade and its cooks are a disappearing breed who use no packaged shortcuts. A little camper catching a small catfish in Blue Hole can usually persuade someone in the kitchen to fry it for him any time of the day. I saw the dining hall in action later that evening, a very different story from the kitchen. The noise even while the boys had their mouths full was earsplitting, and I saw one child stuff two pieces of bread into his mouth before attempting to chew. Si apologized for the atrocious manners, “We make some attempts, but it’s even hard to find counselors who know how to eat in public anymore.” Ben Barnes once won the Double Doily Award for having both elbows on the table while visiting his son Greg at mealtime.

Campers who attend Stewart for five years may get a second chance to polish their manners. Fred Pool, a former executive with the East Texas Chamber of Commerce and Si Ragsdale’s long-time friend, takes a group of older Stewart boys for a week in Monterrey and Saltillo every summer during the camp session. Mr. Pool, who speaks fluent Spanish, introduces the boys to the cultural and culinary pleasures of Mexico, considered an essential part of a Texas gentleman’s education.

The camp motto hangs on a wall in the dining hall. “Don’t Wait ’Till You Are a Man to be Great—Be a Great Boy.” This is implemented with “Thoughts for the Day” and “Pow Wows,” brief meetings when distinguished visitors, counselors, or campers share their experiences. Stewart also offers its members a chance to perfect their interests by bringing in specialists like “Rooster” Andrews to teach a football kicking clinic, Rex Cobble for a calf-roping exhibition, or Steve Farish, professor of music at North Texas State University, for vocal instruction. The athletic clinics keep Stewart competitive with the sports specialty camps that have sprung up in recent years. But Stewart is interested in more than building athletes. As Si said, “Parents who send their boys to Stewart don’t want their boys to be coaches, so we try to hire college students with professional ambitions, doctors or lawyers, to be in-cabin counselors.”

Stewart accepts boys aged six through sixteen. The night I spent there, after a stunt performance before a huge bonfire, my maternal instincts got the best of me. The youngest campers with meringue crusted in their hair from a pie-eating contest looked too young to be away from their mothers for four or five weeks. Kathy Ragsdale, the camp’s business manager, handles homesick boys with aplomb. Giving an extra warm hug to a little camper eyeing the Ragsdale telephone, Kathy, with her Sulfur Springs drawl quietly comforted, ‘‘Sweetheart, we’ll call your mama tomorrah, you just go on to sleep tonaht.”

Tex and Pat Robertson, the executive directors of Camp Longhorn are acknowledged by other directors to be Mr. and Mrs. Camp in Texas. Their operation in Burnet on Inks Lake offers three 24-day sessions a summer. Five hundred campers aged eight to sixteen fill each term. Everyone knows someone who’s been to Longhorn, and that may in part account for its popularity.

In the truest sense of the word. Longhorn doesn’t really qualify as a camp. As one young Stewart camper said, “My friends who go to Longhorn don’t do very much that they couldn’t do here in Dallas.” Longhorn campers don’t go on overnights, seldom hike or even ride. (Longhorn has only 38 horses.) Nature study is limited to a small petting zoo in the middle of the complex. Furthermore, it’s hot in Burnet, with only an occasional scrub oak for shade. And yet, 1500 kids can hardly wait to go back each summer. Tex says, “Longhorn is so many things—it’s health, happiness, love of God and country, manners, friendship, and training in activity skills. It’s also a place where young people can be counselors.”

I talked with Tex briefly in his office before touring Longhorn. It had been a hard summer for him. Federal hearings in Washington on youth camp safety had been scheduled at a time when directors could least afford to leave their camps to testify. A contemporary of Gerald Ford’s at the University of Michigan, Tex is suntanned, silver-haired, and physically fit.

Tex had so much to tell me about the evils of federal control that I hardly had time to get the basics on the camp. Longhorn for Boys and Longhorn for Girls are separate camps; however, Chow Hall is a common dining room, and occasional activities are coeducational. Former campers have assured me that they were very much aware of the opposite sex while at Longhorn.

Quite frankly I have never seen so much teenage pulchritude under one roof as I did at Chow Hall. Features were regular, teeth straight, bodies perfectly proportioned. The most beautiful were the counselors, who were fairly easy to spot since most wore sorority or fraternity tee shirts. Indeed Longhorn seemed to be the most obvious prelude to UT greek life that I had seen all summer; 64 of the 113 college-age counselors were from the University. Orange and white colors everything from camp vehicles to sports equipment.

Longhorn is principally known for its water sports. Tex is a former Olympic swimmer, so it’s not surprising that a timed mile swim is one of the major competitive events. Offerings include water skiing, water polo, diving, scuba diving, and “blobbing,” a Longhorn original. Created by boys’ camp director Bill Johnson, the “blob” is a huge orange and white, whalelike inflated plastic float. It is much like a trampoline, though much harder to stay on.

Another popular activity at Longhorn seems to be collecting Merits, small plastic tokens earned by good behavior that are negotiable only at the camp store. The store is a child’s fantasy world of sporting equipment—not just baseballs and Ping-Pong paddles, but ten-speed bicycles, water skis, and expensive tennis racquets. A kid seldom stops to realize that merits sufficient to purchase a bicycle would probably require attending camp at least eight years, which would cost his parents approximately $4000. Merits are also sent to Longhorn campers on their birthdays. Around Christmastime a staff member delivers the Longhorn Yearbook, a thick orange and white volume containing pictures of the campers and counselors and candid shots of the past summer. During this visit, the staff member inspects the camper’s room; for every memento of Longhorn found there, another Merit is awarded. Recruiting carnivals at country clubs in major cities allow prospective campers to win Merits playing games. This merit system is apparently so successful in keeping misbehavior down and camp attendance up that it has been adopted by neighboring camps like Champion, a newer camp which boasts Darrell Royal as a stockholder.

Longhorn’s site is almost as crowded with buildings as the University of Texas campus. Enough cabins to house 500 somehow diminish the feeling of wide open spaces normally associated with camp. Longhorn’s only claim to real rusticity is that cabins lack electricity and running water. (But bathhouses with both are less than ten yards away.) Well-tended carpet grass makes shoes superfluous.

Aside from the chance it offers to glimpse the opposite sex, the dining hall is a purely functional cafeteria. Campers eat on metal army-type trays, which they must wash after each meal. A Waldemar camper who later served as a counselor at Longhorn said, “My father almost didn’t let me stay after he saw the food. I couldn’t write him that part of my duties as counselor included clipping the hedge.”

Counselors told me that they felt a strong obligation to keep the kids happy and entertained. Longhorn is not big on tearful sentiment and its closing ceremonies are quick and painless.

- More About:

- TM Classics

- Longreads

- Kerrville