Ben Dunn was giddy with excitement as he arrived at the Royal Collegiate Church of Santa María La Mayor in Málaga, Spain. The majestic stone façade and gothic spires of the Renaissance cathedral loomed, demanding his attention the way they had demanded that of visitors for nearly 500 years. But Dunn was captivated by another sight on this morning in March 2019: a group of young actresses and actors, on set for the first week of filming Netflix’s Warrior Nun, the culmination of an idea that had started as some sketches in his notebook 25 years earlier.

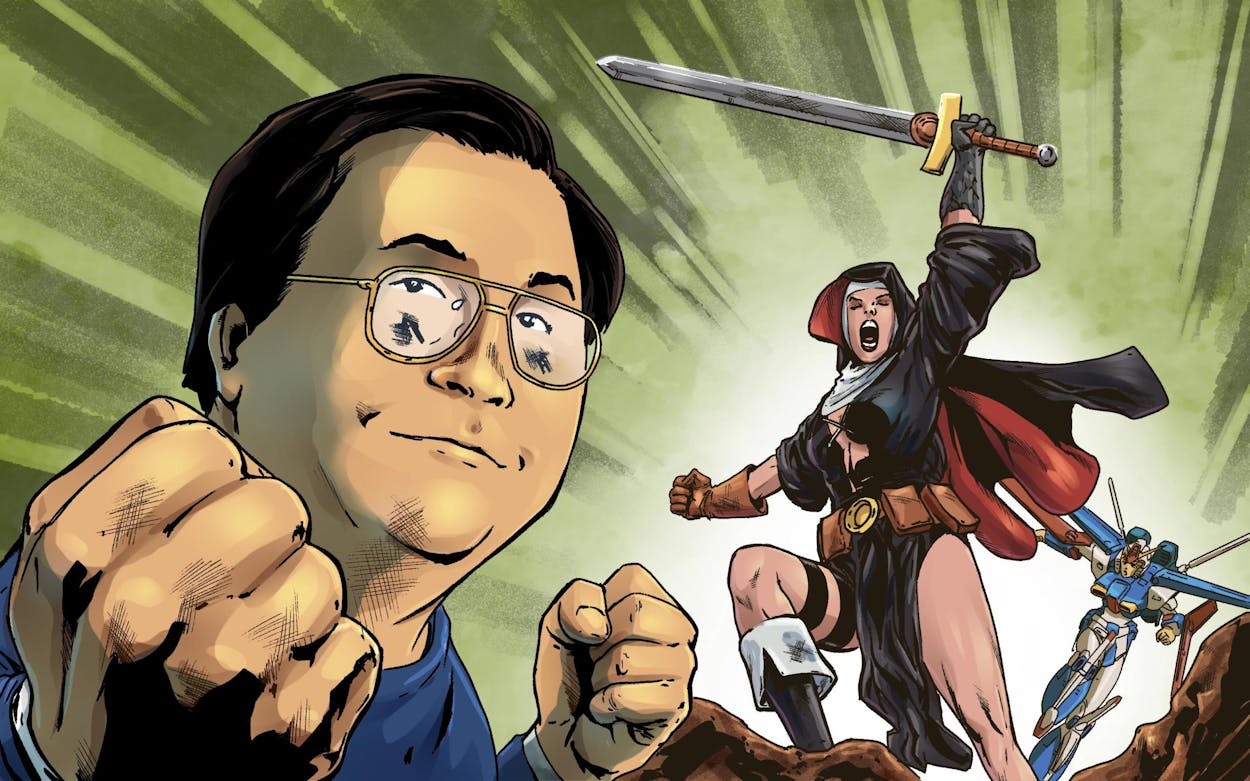

Dunn had created Warrior Nun Areala in 1994 as a comic book for Antarctic Press, the San Antonio–based small press he cofounded a decade earlier. The series told the story of an order of nuns, imbued with holy power and tasked with fighting demons. It was a spin on the “bad girl” trend that was popular in comics in the early nineties, mixed with a healthy dose of ideas from Dunn’s religious upbringing, which included four years at San Antonio’s Central Catholic Marianist High School. He outfitted his heroes—Sister Shannon Masters, Shotgun Mary, Lilith, the Demon Princess—in impractical garb (the titular Warrior Nun’s legs were bare, save for a pair of leather, thigh-high boots) and sent them crashing onto comic-book store shelves. It was an immediate hit.

Over the next twenty years, Dunn would flirt with Hollywood, but the interest always fizzled out. In the mid-nineties, Antarctic commissioned a one-minute, anime-influenced teaser to take to executives who had made other independent comic books of the era into hit shows—he imagined it fitting in alongside HBO’s Spawn and MTV’s The Maxx—but never found a buyer. Dunn continued publishing other comics, with Warrior Nun Areala never far from his heart. In 2009, he was approached by Dean English, a Canadian independent film producer, to pitch Warrior Nun as a movie.

English’s project hit similar dead ends, until, in 2015, he took the script to a friend, Simon Barry, to ask him to rewrite it. Barry identified the problem: the dense story, packed with mythology, wasn’t a movie at all. It was a TV series. Suddenly, the doors to Hollywood unlocked. Barry, who was working on the fantasy series Van Helsing and Ghost Wars when English approached, refined the Warrior Nun idea over the next few years, before taking it to Netflix, which jumped at the concept. Production began in March 2019, shooting on location in the streets and cathedrals of Spain.

English arranged for Dunn to visit the set in Málaga, and that was where he met Shotgun Mary. Toya Turner, the actress tasked with bringing Dunn’s character to life, saw him while the cast was preparing for the day’s stunt workshop. According to English, she froze in her tracks when she spotted him.

“When Ben first met [Turner], she just started to tear up, because she’d read the whole story, and then there’s the guy who created it,” English recalls. “And then Ben started to tear up. And then I started to tear up watching it. It was like, ‘Oh my god, everybody’s crying—in combat training.”

Warrior Nun premiered on Netflix in early July and began finding its audience over the next few weeks. The series was popular in the U.S., but it quickly became an even bigger hit globally, growing its international audience by more than 8,000 percent by the end of the month. Netflix announced in late August that the show had officially been renewed for a second season. “If someone had asked, ‘What was your greatest expectation?’ it was that we would crawl across the finish line to get season two,” English says. “Then you insert a month, and for July, we’re the number one [scripted] show worldwide on Netflix.”

None of this seemed even remotely possible to Dunn when, back in 1984, he took a few thousand dollars in borrowed money and started a comic book company in a converted carport in his parents’ house in San Antonio. Now, as his Warrior Nun captures the imaginations of fans around the world, the 56-year-old Texan has seen his characters go places he never expected. The question he keeps asking himself: how did he get so lucky?

It was 1984, and Ben Dunn had a dream. It was full of ninjas, giant robots, and scantily clad, sword-wielding, demon-slaying nuns. It had started, as all good dreams do, in childhood, when the comic book–obsessed oldest son of Taiwanese immigrants was growing up in San Antonio, where his family had moved when Ben was five. He filled sketchbooks with drawings of comic book characters—his favorites included Richie Rich and the X-Men—and his obsession only grew when his family spent six months in Taipei when he was twelve. There, Dunn discovered Japanese comics and animation, sharing the thick volumes of manga anthologies with his younger brother, Joe. Dunn was immediately captivated upon learning that comics could look and feel different than just the American superheroes he’d grown up with. His family returned to Texas, Dunn graduated from Central Catholic Marianist High School in 1982, and by 1984 he was a twenty-year-old business marketing major at St. Mary’s University, sketching heroes, villains, robots, and ninjas in the margins of his notebook during class.

While at St. Mary’s, Dunn decided to realize his dream. He partnered with a classmate to launch his own comic book company, borrowing $5,000 to pay for printing and distribution of the company’s first title: an anthology collecting the work of other American writers and artists who were raised on superheroes but who grew to enjoy Japanese comics. He called it Mangazine. The title, published in August 1985, was advertised in the Comics Buyer’s Guide and other trade publications, and quickly found an audience hungry for new, American manga comics—the first print run of five thousand copies promptly sold out—and Antarctic Press was born.

The comic book industry of the eighties was in the process of reinventing itself. Self-publishing, once the realm of underground “comix” sold at head shops, had begun to prove itself viable in the nascent direct market of comic book specialty stores. Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, which was self-published in May 1984, quickly became a phenomenon, and Dunn was inspired by the series. “When the Turtles came out, it really opened the door for other small publishers,” Dunn says. He and his partner, Marc Ripley—whom he bought out early on—saw a way to reach beyond Marvel and DC fans to the older readers who frequented the hobby shops that had begun opening across the country. They wanted to name the publisher Penguin Press (“We liked penguins,” Dunn says), but after learning of the famed British publishing house of the same name, went with Antarctic instead.

Being based in San Antonio presented some challenges. There were no printers in the city capable of putting out an entire comic book in 1985, so Dunn had to assemble the first issue of Mangazine piecemeal, using two different printers for the covers and the interior pages. Then, he had to schlep the printed pages in the backseat of his 1972 Chevy Nova to a third location, where the issue was cut and bound. But Dunn says being based in San Antonio provided opportunities, too—especially the sense of camaraderie and support he found within the city’s small, tight-knit art community. “Talent is anywhere, and can come in the most unexpected places,” he says. “I made a lot of friends who were also into comics, and we gathered together to make the best comics we could.”

Dunn followed up the anthology-style Mangazine by launching titles based on his own characters. In 1987, he debuted Ninja High School, and then in 1994, Antarctic published the first issue of Warrior Nun Areala, which was an instant hit. The early nineties were a boom time for the industry, fueled by collectors lured in by rapidly appreciating prices on stuns like the death of Superman and a wave of “hologram”-style covers, and Antarctic rode the success of Ninja High School and Warrior Nun Areala to become a top-ten publisher. But independent comic book publishing is rarely lucrative, and as the speculative market went bust, publishers who had been selling hundreds of thousands of copies a month just a few years earlier disappeared.

Antarctic didn’t, though. Joe came in to manage the company’s finances, and he had a pragmatic philosophy that kept the publisher solvent even as the industry shrunk around it. “Number one is you’ve got to pay your printer,” the younger Dunn laughs. “There were days that I finished paying the payroll and the printers, and we had like $2.60 in the bank, and I would sit back and say, ‘Look, we did it.’”

Joe Dunn says he never took a paycheck from Antarctic Press; an internal medicine physician and acupuncturist, he’s run the business side of the company on evenings and weekends, enjoying the opportunity to be a part of the comics he and his brother fell in love with as children. They started recruiting other creators and publishing their titles, allowing the writers and artists to maintain full ownership—an unusual arrangement in the comics industry at the time—and bringing in a “bullpen” of talent to work out of the office park the Dunns’ parents purchased near Ingram Park Mall. In addition to Warrior Nun, they’ve had other series develop followings, including Fred Perry’s Gold Digger, which has been published continuously by Antarctic since 1992, as well as the early issues of award-winning hits like Terry Moore’s Strangers in Paradise and Alex Robinson’s Box Office Poison. Ben Dunn took occasional gigs in Hollywood, doing storyboards for the cartoon The Real Ghostbusters or working as an animator on Richard Linklater’s A Scanner Darkly, but he let the dream that Warrior Nun or Ninja High School might become household names fade.

“We’ve been in this business for 35 years, and every few years, someone comes up and says, ‘We’re going to do a movie! We’re going to do a TV show!’ At the beginning, you get all excited,” Joe Dunn says. “And then after 35 years, you go, ‘Okay, that’s fine.’ We’ve heard it before.”

There’s no one to whom the 25-year odyssey of Warrior Nun seems more unlikely than the Dunn brothers. From an animated teaser Dunn couldn’t sell, to a screenplay that Dean English never quite cracked, to a TV idea that Simon Barry walked into Netflix with and walked out with a series order, it’s a path they never predicted. But now that the show is a hit, they’re trying to enjoy the ride as best they can.

Ben Dunn is a happy guy. He says that a lot. “I’m extraordinarily happy and proud of what I’ve accomplished,” he says. “I’m very satisfied with how things are going.” He’s shy at first, at least on the phone, but quickly lets loose with stories from his career in comics. He’s happy with his life—in Mesquite now, where he and his wife, along with their two kids and three cats, relocated to take care of her parents—and proud of the fact that Antarctic has survived as other publishers have struggled. Warrior Nun Areala had a dark edge to it, but over the phone calls and Zoom meetings that define the pandemic era, you don’t see much of that in its creator.

In her original incarnation, Warrior Nun Areala was part of the “bad girl” wave that crested in the mid-nineties, when improbably proportioned heroines in skintight costumes wielded swords, guns, and whips to fight crime or monsters or whatever, all to the delight of mostly male, mostly adolescent fans. Sister Shannon Masters and Shotgun Mary fit in well alongside them, even if the concept of scantily clad nuns with ninja swords and heavy guns raised some controversy among Catholics, too. The U.S. Catholic League condemned the “sexy, violent nuns” of the comic book, and Dunn believes that the racy nature made it a tough sell in Hollywood back in the nineties. “We went to several studios, and almost every single one of them thought it was just too controversial,” he says.

That made it easier for Dunn to embrace the reimagining that Simon Barry had in mind when he took the property to Netflix. Barry was a fan of the mythology Dunn created for Warrior Nun Areala, but wanted to reframe the perspective. Rather than create a series that tried to appeal to teenage boys, he saw a concept that could speak to young women who might relate to the story’s heroes. “I liked that it was an unapologetic take on this secret sect of fighting nuns, and the heavy-metal attitude,” Barry says. “When we were putting the show together, we definitely wanted to preserve that take-no-prisoners approach and some of the more extreme, operatic notes … even as we were looking at making this more about empowered women in a way that was more 2020 than early nineties.” Ava, the protagonist of Netflix’s Warrior Nun, and her demon-fighting sisters wear sensible tactical gear, their legs and chests covered and protected from whatever monsters menace them.

Dunn doesn’t seem to mind the changes. “I know that things have to be adapted, and are not necessarily a 100 percent adaptation of your material, and that’s fine,” he says. “The most important thing is that I get to share something I created with a larger audience.” He still recognizes his characters in the versions that appeared in the series, even if they’re wearing more practical outfits. “She’s right there on the screen,” Dunn says. “It’s amazing to see it come to life.” That attitude made it easy for Barry to give Dunn a glimpse of the process, whereas other creators of intellectual property sometimes fret about what’s happening to their baby. Barry had Dunn meet with the writers’ room for the series via a videoconference, and invited him out to Spain for his visit to the set once shooting started.

“We were all on the same page that we were deviating heavily from the book,” Barry says. “But he had a genuine curiosity about how shows get made, how adaptations function, and how writers’ rooms work, and we definitely wanted to get his blessing.”

Dunn’s curiosity might serve him well. He hopes that the success of Warrior Nun may be what it takes to get Hollywood interested in Ninja High School, which he’s also working with Dean English to develop. According to his brother, Antarctic Press has already started seeing some renewed interest in its comics since the show’s premiere, and the crowdfunding campaigns that allow the publisher to take chances on projects like hardcover collector’s editions and inter-company crossovers have been getting more support too. Even if Ben Dunn’s Hollywood adventure ends with Warrior Nun, after 25 years of knocking on that door, he knows he’s lucky just to be there—everything else is a bonus.

“I never would have thought I’d have gotten this far,” Dunn says. “If something new happens, great. If not, then I’ll just keep doing the comic book. I’m a very patient man. But if it doesn’t, I’ll be happy. I would just keep doing comics until I shuffle this mortal coil.”

- More About:

- Film & TV

- Art

- Television