When my friend Hortencia “Tense” Vitali was growing up in Laredo in the seventies, tamale making was a Thanksgiving ritual as keenly anticipated as the holiday itself. As I listened to her stories of the fun that she and her siblings had helping her mother prepare mountains of these savory treats, I felt quite deprived that I had not grown up in a large Hispanic family. “There were ten of us kids,” says Tense, who is now 38 and an Austin interior designer, “plus a cook, a housekeeper, and of course my mom and dad, and even my littlest brothers and sisters had their part to do. It was a huge affair.”

The preparations began two days before T Day, when Candelaria Cisneros and a contingent of her children would drive downtown to La Fe, “a big, old ceiling fan-cooled masa factory,” to pick up her order of the corn dough that would enclose the tamales’ central filling. Mrs. Cisneros was particular about quality and insisted on finely ground white masa, not yellow, which she considered inferior. Because this was before the widespread use of dehydrated masa, factories like La Fe started with real corn, and a warm, almost sweet aroma emanated from dozens of dough mixers. The next stop was the butcher shop, where Mrs. Cisneros picked up a whole, cut-up pig—head, feet, and all. The shoulder meat would be set aside for the tamales and the rest frozen for other uses such as barbacoa. Then it was across the border to Nuevo Laredo’s open-air market to sift through piles of dried corn husks, strings of garlic, cinnamon sticks, and dark red ancho chiles.

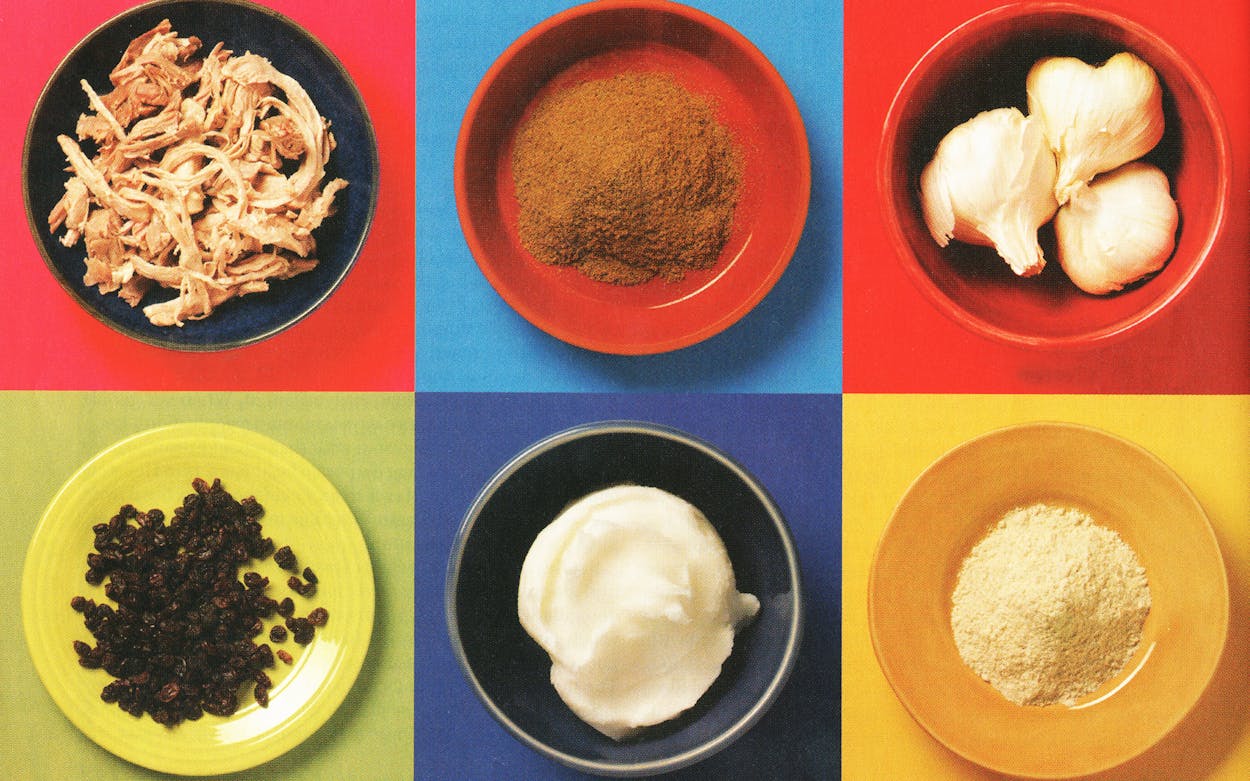

When they got back home, Mrs. Cisneros tied on her apron and began the serious work of cooking the pork and getting the masa ready. The next day the family tamale team was marshaled, with plenty of hot chocolate on hand for the children and beer for the adults. It was a regular assembly line. “We had the ones who soaked the corn husks to make them pliable and pulled off the silk,” says Tense, “then the ones who spread the masa on the husks.” Another person carefully put a dab of chile-and-cumin-seasoned meat and exactly three raisins in each of the bite-size tamales, and still others rolled and tucked the shucks into the familiar tubular shape. The last one stacked them in the steamers. As many as 55 dozen would be made at Thanksgiving, both the pork version and cinnamony, raisin-filled sweet tamales, and half of them would be frozen for Christmas. There was no such thing as too many tamales. After the interminable hour that it took them to steam on top of the stove, the first ones were gingerly unwrapped and eaten, straight from the shucks.

Tamales are fiesta food. In Hispanic communities throughout the United States, they signal times for celebration, such as New Year’s and Mexico’s two independence days, el Cinco de Mayo and el Diez y Seis de Septiembre. They are also obligatory for more solemn occasions like el Día de los Muertos (the Day of the Dead) on November 1 and 2, when departed loved ones are remembered with home altars decorated with the honoree’s favorite things (a vase of lilies, a Spurs jersey, a bottle of Tecate). But these masa snacks don’t require a holiday to be enjoyed; bowls and platters brimming with them also make their appearance at birthdays, wedding showers, and family reunions. In other words, at the kinds of events where Anglos would typically be milling about balancing a plate of finger sandwiches and a glass of wine, chances are tradition-minded Latinos will be peeling the husks off tamales.

Tamales are among the most ancient foods of the New World, dating back at least two thousand years. To the Maya, who lived in and around what is now Central America and Mexico’s Yucatán Peninsula, the tamale was the cultural equivalent of our cheeseburger. A graceful drawing on a vase discovered at the ruins of Tikal, in Guatemala, shows a well-fed noble in a feather headdress sitting cross-legged in front of a bowl of neatly rolled tamales. It was the Aztecs of central Mexico, though, who were the masters of the tamale universe, making the handy packages in a multitude of shapes (little canoes, animals) and colors of masa (white, red, yellow). Chile-spiked turkey and dog meat were favorite fillings. The word “tamale”—the correct singular form in Spanish is tamal, by the way—is derived from “tamalli,” a word in the Aztec language, Nahuatl.

Although many elements of Mexico’s indigenous cultures vanished forever with the coming of the conquistadores in 1519, tamales survived. In fact, if it hadn’t been for the Spanish and the boatloads of squealing pigs they brought with them, modern-day tamales would lack their second most important ingredient after corn: lard, which gives the masa flavor and flexibility. (Pre-Hispanic tamales were more like thick steamed tortillas—”tender and quivery,” in the words of cookbook author Rick Bayless.) Today the variety of tamales made in Mexico and other parts of the Latin world is astonishing. Around Tampico, in eastern Mexico, giant sacahuiles, swathed in banana leaves and big enough for a whole pork loin, emerge from adobe ovens. In Sinaloa, in the western part of the country, tamales of almost equal girth are filled with a veritable stew of pork, zucchini, potatoes, green beans, plantains, and serrano chiles. The far southern state of Chiapas has its iguana tamales. In her cookbook The Cuisines of Mexico, Diana Kennedy wrote of tamales from coastal Campeche that are made with a near-transparent dough, “so delicate that it trembles at a touch.”

But as vast and intriguing as these varieties may be, we Texans know what a tamale is, and we’re not messing with it. It’s true that certain modern American chefs, Dallas’ own Stephan Pyles among them, have played fast and loose with the whole notion, making masa-less tamales of arborio rice pudding or apples in brioche pastry that would startle even the ancient Aztecs. But for most of us, whatever our heritage, the familiar, homely cylinder of masa remains the gold standard. We may flirt with exotic types, but in these uncertain times there is much to be said for simplicity, for the ritual of opening a corn husk-wrapped bundle and letting its steamy contents tumble onto our plate. We take a bite of that soft masa coating with its filling of moist, chile-spiked pork and pause. Ah, yes. For a moment, at least, all seems right with the world.

Tamales 101

Inspired by Tense’s childhood memories, I decided to make tamales one night. In the course of doing so, I consulted half a dozen Mexican-food cookbooks and also validated Murphy’s Law (everything that could go wrong did). My tamales looked like miniature loofahs (oddly shaped and full of little holes), but they tasted great. Here are some tips that I gleaned from the process, so that you too can make tamales even if you don’t have a Mexican grandmother to answer questions.

Shopping list. Most ingredients can be found at supermarkets (try the produce section or Mexican-products section for corn husks). Fiesta Mart sells ready-made masa for 50 cents a pound (specify masa for tamales, which is more coarsely ground than tortilla masa). So do tortilla factories and grocery stores in Hispanic neighborhoods. Here is the list of factories.

Wrap stars. You can use a variety of waterproof wrappers to hold the tamale while it cooks: corn shucks, banana leaves, avocado leaves, even plastic wrap. (The latter is a little soulless, but it works great for those odd shapes; you peel it off before serving.) Corn shucks are the most common in Texas, though, so I’ll concentrate on them. To make dried shucks pliable, soak them in a bowl of very hot water for thirty minutes, weighting them with a saucer so they don’t float. (For a pretty holiday presentation, soak them in red hibiscus tea.) Fresh shucks can be used too.

Critical masa. I tried making a few tamales with the fresh ready-made masa that I bought at Fiesta. But I was much happier with the less dense masa I whipped up myself using dry masa harina (again, be sure to get the kind that is specifically for tamales). It was light, almost spongy, and the whole process was as easy as using a cake mix. Maseca is a good brand, but the package instructions aren’t very detailed. So here are some wise words from the experts:

For meat-filled tamales, mix your masa harina with lard and warm chicken stock, using amounts specified on the package; for sweet tamales, use vegetable shortening and warm water. Whichever fat you use, chill it for an hour or so and beat it with a mixer for at least a minute to make it light and fluffy. After you mix the dry masa with warm liquid, add it in batches to the beaten fat. Continue beating the dough for one to three minutes until it is approximately the texture of a butter-cream frosting. The dough is ready if a teaspoon-size chunk floats in a cup of cold water. (A word about lard. I know what you’re thinking: “Yech! Pig fat. No way.” But it’s lower in cholesterol and saturated fat than butter and lower in trans-fats than shortening. It’s also clean and pure white—and meat-filled tamales just don’t taste right without it.)

General assembly. Every cookbook has a different masa-spreading method: Spread it on the middle of the corn husk; no, spread it on the lower half. Cover the husk all the way to the sides; no, leave margins. The truth is, they all work. Here’s the best way I found to make the typical cylindrical Tex-Mex tamale. Pat a corn husk dry and lay it in front of you (if some are too small, overlap two of them and use a dab of masa to stick them together). With a knife or a spatula, spread a scant one-fourth cup of masa into a four-inch square (these measurements do not need to be exact). Leave a border of about two inches at the pointy end of the husk and three fourths of an inch on the other three sides. Spoon your filling of choice down the middle of the square, then lift the two sides of the husk, bring them together to encase the filling, and fold them both to the left. Then fold the pointy flap over them like the flap on an envelope. The other end stays open, but if you prefer, you can fold it over too; just leave more of a margin at that end when you’re smearing on the dough. The finished tamales look cute when tied with thin strips of husk or colored ribbon, but this isn’t necessary.

By the way, there’s nothing sacred about the usual stogie form. You can make tamales any size or shape your heart desires—circular, square, triangular, crescent-shaped, whatever. Mention this when your friends convulse with laughter over your efforts.

Now you’re cooking. Steaming is the most common way of cooking tamales, in a tamale cooker, a vegetable steamer, or whatever you can improvise. Stack the tamales upright in the top part of the steamer, open ends up. Spread extra husks between each layer. Pack the tamales firmly but not tightly, and put a wet, wrung-out dishtowel on the top layer to absorb water that condenses on the lid. Cover the pan and steam for 45 minutes to 2 hours; the time varies tremendously depending on how many you’re cooking and how big they are. Several cookbook authors suggest putting a penny in the water when you start heating it; if it stops dancing about, add more boiling water fast. If the steam is interrupted before your tamales are cooked, they will fall like a cake and be heavy. The tamales are done when the husks come away cleanly from the dough. Let them rest for 5 to 10 minutes in the steamer before serving. To reheat tamales, either leave them in their husks and resteam for 2 to 5 minutes, depending on the quantity; wrap them in foil and put them in a 350 degree oven or toaster oven (allow about 20 minutes for half a dozen); or heat them individually in their husks on an ungreased comal or skillet over a low flame. Microwaving tends to make them tough.

By the book. Here are my favorite cookbooks for tamales, and they’re fun to read too: Rick Bayless’ Mexican Kitchen; Diana Kennedy’s The Essential Cuisines of Mexico; Mark Miller, Stephan Pyles, and John Sedlar’s Tamales!; and Zarela Martínez’s Food From My Heart.