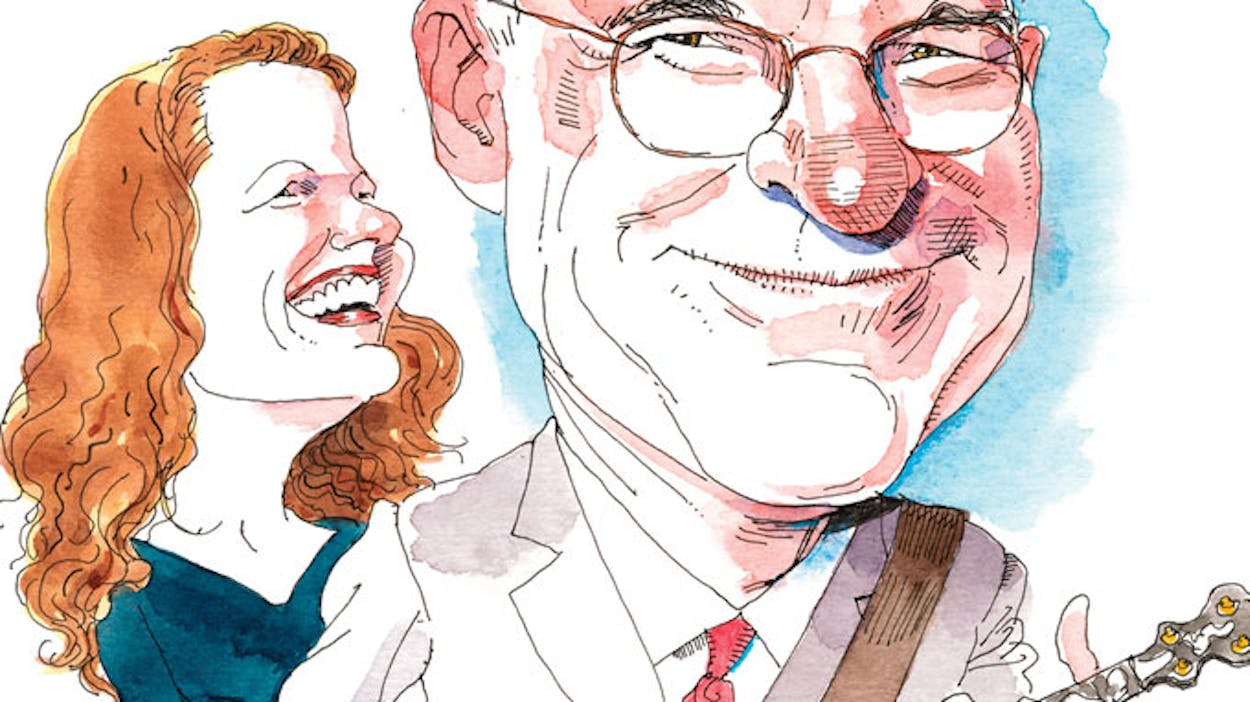

“Absolutely,” Steve Martin says, sitting at a small cocktail table inside the Los Angeles music and comedy club Largo. Though it’s been more than sixty years since his family moved from Waco to Hollywood, Martin considers himself a Texan. It’s the first thing I asked. But the terse, one-word reply and what felt like a quick flash of stink eye made me think I might have opened with a dumb question. It’s easy to develop an inferiority complex around Martin. He’s an iconic multi-hyphenate: a comedian-actor-author-playwright and a formidable banjo player who in recent years has been embraced by the acoustic music world’s A-list. As it turns out, he knows his Texana too: he speaks knowledgeably about the state’s pecan production, Austin’s reputation for live music, and the Amon Carter Museum of American Art’s collection of Western paintings.

Less surprisingly, Edie Brickell also considers herself a Texan. She lives in Connecticut these days, but she was born in Oak Cliff, and in the late eighties she and the New Bohemians established Dallas’s Deep Ellum as the country’s most-talked-about post-Athens, pre-Seattle music scene. She too finds Steve Martin a little intimidating. The pair’s forthcoming album, Love Has Come for You (Rounder Records), was actually born out of that intimidation. The two musicians have been casually acquainted for a long time, through Brickell’s husband, the legendary singer-songwriter Paul Simon. Nearly three years ago, after they bumped into each other at a New York party, Martin asked Brickell to pen lyrics for a banjo piece he’d written. He played it for her live, and Brickell instinctively did what she’s done for years: on the very first listen, she hummed and mumbled gibberish, trying small phrases and random rhymes, feeling her way toward words that would eventually fit.

“He kept asking, ‘Wait, what are you singing?’ ” Brickell says. “I’m used to just singing until a song evolves, but I was so intimidated by his intelligence that I kept thinking, ‘What if he thinks what I’m singing is stupid?’ So I mumbled a lot. And ultimately I asked him if I could just record it on my own and send it back to him.”

After Brickell sent him her initial song—“Sun’s Gonna Shine”—the pair worked up another dozen tunes via email. Martin would write a banjo melody and send a recording of it to Brickell, who would write lyrics, sing them, and send the MP3 back. What seemed, even to them, like an odd pairing quickly led to places they couldn’t have gone to alone. For Martin, it was time to test the musician’s truism that the notes you don’t play can be as powerful as the ones you do—even when it comes to the banjo, which usually encourages maximal, high-velocity picking. “I worked under the premise that a banjo piece could have a lot of air in it and still be very evocative,” says Martin, who played the banjo in his seventies stand-up act and has released two albums based around the instrument, 2009’s Grammy-winning The Crow: New Songs for the Five-String Banjo and 2011’s follow-up, Rare Bird Alert. “Initially the banjo is about technique, but eventually you get to the place where you’re comfortable enough to make music rather than show off.”

Brickell, for her part, saw an opportunity to write in a more linear style than usual. The bulk of the songs on Love Has Come for You read like short stories, with rich characters and beginnings, middles, and ends. The album’s very first lyric is “When you get to Asheville, send me an email,” striking a quirky—and modern—tone for a very traditional-sounding record. Brickell says that while some of the subject matter is based on childhood memories of visiting her grandmother in Paris, Texas, a lot of the language stems from a newfound interest in classic country music. “The warm Texas sensibility is unmistakable in country music,” Brickell says. “The way somebody like Bob Wills talked—‘Roly-poly, daddy’s little fatty’—always reminded me of home. The stories they tell, the little details, intrigued me. And I thought, ‘Wouldn’t it be fun to explore writing that way?’ Then this happened.”

Last summer, the pair gathered their MP3 demos and asked producer Peter Asher (James Taylor, Linda Ronstadt) to help them record an album, with assistance from Austin-based Grammy winner Esperanza Spalding, Nickel Creek alumni Sara and Sean Watkins, and his touring band the Steep Canyon Rangers. And though the songs aren’t particularly funny, the 25-plus live shows Martin and Brickell have planned for the spring and summer will prolong the most significant by-product of Martin’s late-blooming music career: his return to live comedy three decades after he abandoned the form to focus on movies.

“We do a funny show,” says Martin, who has grown comfortable enough with the comedic interludes and interplay with his band that he’s recently begun billing the performances as “music and comedy.” “As a comedian, there’s a freedom the music provides: you do three minutes of comedy and then you play a song. You’re not out there on the hook all the time. In comedy, you’re always two minutes ahead of yourself. It’s ‘What’s next? What’s next? What’s next?’ With music, you’re always in the moment.”

Martin certainly doesn’t always feel the need to be funny (as the hour I spent talking with him certainly bore out). “I’ve been doing things with a bit of emotion in them for a while now,” he says. “I’m known for more than just what I did in 1976. And what I did in 1976 wasn’t sustainable. It takes a kind of energy that would have become fake energy over time. You just can’t act like that when you’re older. It would be fake and look fake.”

Brickell also knows what it’s like to be judged by a first chapter: she was just twenty when “What I Am” conquered pop radio in 1989. After two albums, the New Bohemians parted ways in 1991, largely because Brickell wasn’t having fun. She felt lonely on the road and lonelier still onstage. An introvert playing an extrovert’s game, she didn’t know what to do with herself between verses. “I knew I couldn’t dance, so when I wasn’t singing and all eyes were on me, it made me self-conscious,” she says. She’s released solo records in fits and starts ever since, and while none have measured up sales-wise to her New Bohemians run, she’s more than fine with that; she’s never been conflicted about which side wins the art-versus-commerce debate. When I mention to Martin that Brickell has always seemed far less at ease with fame than he seems to be, he simply says, “She’s a real person.”

Lately, though, there’s been an uptick in her music-biz profile. This will be her fourth album of new material in less than three years, and since last April, as a personal challenge, she has without fail written and recorded a new song every day and posted it on her website. And her tour with Martin will represent her longest run of shows in two decades. Having a bona fide comedy legend next to her onstage seems to have something to do with it. “All I have to do is stand there and sing?” Brickell asks. “That’s one of the greatest reliefs I’ve ever experienced. To stand there next to someone who is going to entertain? Boy, the pressure is off. I can relax and do what I love to do without worrying about letting people down by not offering something more. It’s the dream gig.”

“Dream gig” is also how Brickell describes phase two of her collaboration with Martin: writing a musical. The pair has written a dozen songs for Bright Star, a theatrical piece set in North Carolina in 1945, which they hope to get workshopped this summer. Brickell believes she and Martin have the rarest thing in show business: chemistry.

“One time, we were listening to a playback of a song, toward the end of the week of recording,” Brickell says. “We were sitting behind the board and the banjo solo came on, and he started dancing in his chair, fingers pointing, eyes squinted, arms flailing, giant smile on his face—it was the ‘wild and crazy guy’ dance. When the banjo stopped and I started singing again, he slumped down in his chair and gazed up at the ceiling like he was bored. We all just fell out, cracking up laughing. It was a great moment. Steve Martin can act like he’s bored by your singing and make you feel special at the same time. Who else does that?”

- More About:

- Music