Q: My friends and I were paddling the Devils River in Val Verde County last spring. We drank some beer, we spilled our gear, and before we knew it, it was getting dark and we hadn’t found a good island to camp on. So we pitched a tent on the bank below a bluff. Or at least we’d started to, when the owner of said bluff appeared and loudly informed us that we were on his property and needed to get lost. I know the navigable waters of Texas belong to all Texans, but I thought the banks of a stream were fair game too, since the water sometimes flows over them. Where did I go wrong? Or did I?

Nate B. Spooner, Austin

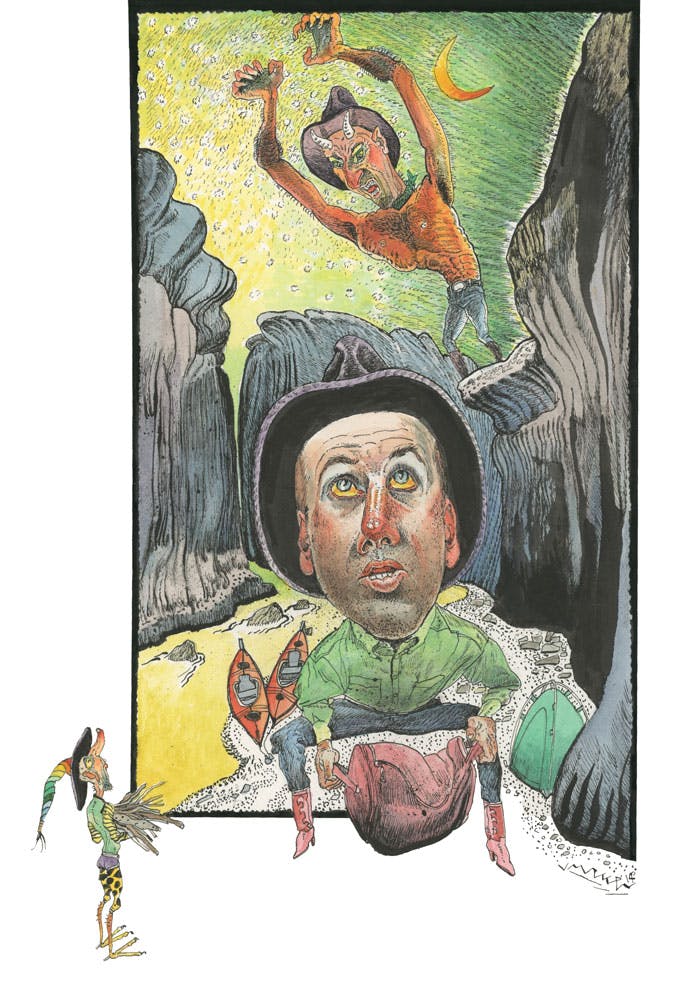

A: The Devils River is prized by paddling enthusiasts for its ruggedness, remoteness, and crystalline pristineness. Additionally, it has been known for the orneriness and occasional gun-totingness of the landowners through whose idyllically craggy properties this demonic yet handsome snake wends its way. As the Devils is bounded almost entirely by these private lands, making camp can pose problems. Islands in the stream offer a good option for an overnight (as well as for one hell of a Kenny Rogers and Dolly Parton duet) if, as they say, the good Lord is willing and the river don’t rise, which it sometimes very rapidly does. But even the best-laid plans can be affected by a fast-setting sun, paddle-weary muscles, and a beckoning cooler full of ice-cold beer. Clearly this is what happened on your trip.

The navigable waters of Texas do indeed belong to all Texans. And so do the streambeds upon which they flow. The problem is that the exact line demarcating the parts of the streambed belonging to the public and the parts belonging to private parties, a border known as the gradient boundary, is not always an obvious one. The Supreme Court of Texas has defined the streambed as the “soil which is alternately covered and left bare as there may be an increase or diminution in the supply of water, and which is adequate to contain it at its average and mean stage during an entire year, without reference to the extra freshets of the winter or spring or the extreme droughts of the summer or autumn”; further, the court has located the gradient boundary “midway between the lower level of the flowing water that just reaches the cut bank, and the higher level of it that just does not overtop the cut bank.”

This information, pertinent though it may be, leaves the Texanist’s head aswirl in an eddy of words, and an attempt to explain such a befuddlement to that landowner, with his nostrils flaring as they were, would most assuredly have been a fruitless endeavor. Ideally, river trips go according to plan, and camp is made without incident at a prearranged, legal spot. Occasionally, though, things do not go as planned. In these situations it’s the Texanist’s hope that reasonable heads prevail. As you survived to write this letter, it appears to have worked out this way for you and your party. Congratulations.

Q: I am a fairly new resident of the Lone Star State, having recently transplanted from Chicago, so the only thing I know about cowboy boots is that I want a pair. I’ve been browsing online and at a local Western wear retailer, and I am a little confused about what kind of heel I need. I understand that there are riding heels and walking heels, which seem to be self-explanatory, but even though I’ll be doing 100 percent more walking than horseback riding, I think I prefer the look of a riding heel. Is it acceptable to use riding heels for walking?

Andrew Black, Houston

A: It was once the case that the heels of boots, much as the boots themselves, were constructed with a functionalist design principle. The boot’s high shaft helped protect the wearer’s leg from saddle rub, mesquite thorns, rocks, snakebites, and the like, while the oversized heel kept the boot from slipping through a stirrup. Working cowboys and country folk appreciate these elements still, but for the general public, boots really need only look good on the outside and feel good on the inside to serve their purpose. The shorter and broader walking heel is a fine option, but if a riding heel suits you, the Texanist would advise you to proceed in that direction. And you may do so, even in your new boots with the riding heels, at a walk.

Q: Texas has a number of towns with peculiar names, but Cut and Shoot has to take the cake. Where in the world did that name come from?

Vickie Gonzalez, Waco

A: Local lore places the origins of the name of this Montgomery County town at the footsteps of a local church-slash-schoolhouse known as the Community House. As legend has it, all denominations were welcome to make use of the Community House except Mormons and Apostolics, but in July 1912 an Apostolic preacher declared his intention to preach there, which divided the community fiercely. Thankfully, no actual cutting or shooting ensued. Instead, it is said that an eight-year-old boy, frightened by the increasing frothiness among the townspeople, proclaimed that he intended to “cut around the corner and shoot through the bushes.” The rest is history.

For the record, the Texanist also likes Red Ranger, a tiny spot east of Temple, in Bell County, which according to the Texanist’s family lore was named by his grandfather in honor of Red Ranger cigars.

Q: If a group of people are using a friend’s river house for the weekend but the homeowner isn’t there, is it permissible for the husband of one of the guests to pull a .22 rifle out of a closet, load it up, and start taking potshots at turtles, frogs, a small snake, floating pieces of Styrofoam, and a whole slew of other harmless objects?

Name Withheld, Kerrville

A: The Texanist is a man of many pastimes, and plinking with his trusty .22 is one of his favorites. The Texanist also likes being invited to stay at the river houses of friends. It makes for an especially good time when he has the opportunity to combine these two loves into one happening. But before the Texanist is allowed to commence fire on such occasions, a few things have to fall into place. The husband of the houseguest in question appears to have erred on numerous fronts with regard to basic etiquette as it applies to both river house visitation and guns. You can’t just show up at a person’s second home, load up the first gun you find, and start spraying hot lead all over the place without express permission from the home’s owner. Common courtesy and good sense tell us this. The Texanist’s experience is that certain ground rules are usually made clear beforehand in these situations. The homeowner might offer something like, “Y’all can swim in the river. There’s beer in the fridge. Please use the fire pit out back. Also, we left a .22 in the closet and there are bullets on the shelf. Feel free to plink at will. It’s open season on turtles, frogs, small snakes, and Styrofoam. Have fun!” Or the guest, in a similar exchange, might ask something like, “Is it okay to bring a .22? Pauline’s husband has never shot one and I want to teach him. Oh, okay. You have a strict no-guns policy. I see. No problem. Thanks for letting us use the house.”

The Texanist is no fuddy-duddy, but if it were his river house and his .22 that this yahoo misused, it’s safe to say that it would be this fella’s last time to stand upon the Texanist’s river house welcome mat. Enjoying the generosity of friends is one thing; filling that generosity full of disrespectful .22 caliber bullet holes while ungratefully running roughshod over it is another.

The Texanist’s Little-Known Fact of the Month: Lang Field, home of San Antonio’s St. Anthony’s Catholic High School Yellow Jackets, was constructed in 1910 and is the oldest football field in Texas. This season’s varsity home opener (and homecoming) is set for September 27 against the Spartans of St. Stephen’s Episcopal from Austin. Good luck, Yellow Jackets!