Q:

I recently took my born-and-bred South Texas girls to visit their Longview cousins, and on our final night behind the Pine Curtain, we were graciously invited to a shindig that involved a piñata. My girls were quite astute at piñata dismantling, while the East Texas kids rarely made contact with the papier- mâché piglet. I think the advantage was due to the fact that my offspring were raised in a heavily Hispanic culture. Is this phenomenon widely known, or have I made an important anthropological discovery?

Wendy McHaney, Victoria

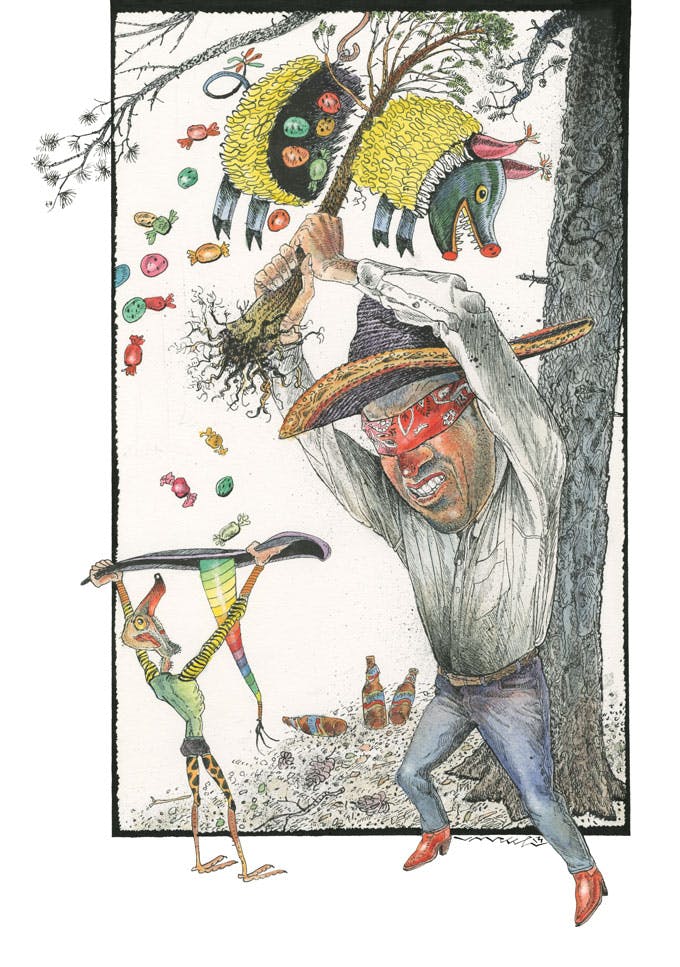

A: Piñatologists tell us that these brightly colored, goody-filled, dangling party enhancers made their way to Texas via Mexico, where they were introduced by the Spanish, who learned about them from the Italians, who got wind of them from Marco Polo after he visited China in the thirteenth century. They go on to tell us that the name “piñata” is actually believed to have derived from pigna, the Italian word for—drumroll, please—“pinecone”! The Texanist knows, right? East Texas. Pine Curtain. Pinecones. Piñatas. Weird. Anyway, by the time the European piñata made landfall in North America, it was already being utilized by Christians in Lenten celebrations. Fortuitously for the conquering Spaniards, both the Aztecs and the Mayans had their own indigenous piñata-like traditions, and the missionaries were able to entice would-be converts with their fancier European-style booty-stuffed vessels—not to mention the blindfolds and sticks. May the Texanist have a glass of water? Thank you. Whew, that was so much more of a piñata history lesson than he intended. And so much more interesting than he would have ever thought an off-the-cuff lecture, to one day be formally entitled “Brutal Papers: The Colorful and Violent History of the Piñata,” could be.

Now, about this South Texas versus East Texas piñata-whacking hypothesis of yours: the Texanist is skeptical. It seems to him that while the children of South Texas probably do, as you suppose, attend more social functions that feature piñatas than do East Texas kids, this doesn’t necessarily mean that they are inherently better club wielders. In fact, it’s the East Texans, with their timber culture, abundant pinecones, and easy access to sticks, whom you would expect to prevail in this department. And then there is the blindfold, the great piñata equalizer. How do you explain that? The Texanist suspects that the polite hosts of the Piney Woods fiesta y’all attended were just generous with the piñata rope when it was your girls’ turns. But really, the important thing to remember is that it doesn’t matter who among us causes the candy and prizes to spill, so long as the candy and prizes do eventually spill.

Q: When I was growing up, it was always a thrilling treat to get to ride in the back of my dad’s pickup, even though we did it all the time. The other day I pulled up to the home of a friend of my son’s to pick him up for a playdate, and when I told the friend to hop in the back, his mother canceled the playdate. Later that day I got an email from her in which she accused me of child endangerment for letting my son ride in the back and said she wouldn’t allow her son to visit our house again. Tell me she’s overreacting.

Name Withheld

A: Up until the time the Texanist was licensed to operate a motor vehicle by the great state of Texas, his favored mode of getting from point A to point B was also in the back of a pickup. Just as soon as he was able to load himself up, this is how he got around. “We’re going to Clem’s for dinner. Get in the truck.” “You have a dentist’s appointment. Get in the truck.” “We’re late for church. Hurry up! Get in the truck!” And it continued into adolescence. “Texanist, you wanna go frog-gigging? Get in the truck.” “Texanist, you wanna go out to the lake? Get in the truck.” “Texanist, you wanna go cruise Fifty-seventh Street? Get in the truck.” It’s a safe bet that before getting his own wheels, the Texanist spent more time in the backs of trucks than he did in the cabs of trucks. This is how it was for many a young Texan. Arms outstretched like the wings of a roaring fighter jet, the wind whipping through his ample seventies hairdo, and an unfurled tongue flapping in the breeze like that of a happy, happy hound—the Texanist was the king of the world! Or the king of Central Texas! Or maybe the king of Temple. He was at least the king of certain outlying roads in the vicinity of Temple. Of that he is sure. These were good times. Thinking back, the Texanist figures that his last open-air ride of any real distance occurred during his early college years, when, the day after an exceptionally festive summer fraternity party, he was transported supine all the way from Houston to Austin in the bed of a pal’s pickup. Good times, indeed.

But that was then. In the modern era, all of those aforementioned rides, except for the hangover express, would run headlong into the law, which forbids the transport of anyone under the age of eighteen in an open pickup bed. There are exceptions for parades, hayrides, beach driving, one-car families whose one car is a truck, and the transport of farmworkers on country roads, but otherwise you could be looking at a fine of anywhere from $25 to $200. Yet another lamentable reality brought on by well-intentioned spoilsports with everybody’s best interests in mind. Getting back to your question: even though you were in clear violation of the law, it does appear that your son’s friend’s mom did react somewhat excessively. But tell the Texanist this: How many empty beer cans had you allowed to accumulate back there? Just asking.

Q: One of my co-workers, who grew up in Missouri, told me that the reason Texas has wild turkeys is that Missouri traded turkeys for Texas armadillos. I was born and raised in Texas, and I have never heard this story. She claims she is right, but I think it is hogwash. Can you set her straight?

Lisa Skelton Parman, Via Facebook

A: It appears that this Show Me State colleague of yours is attempting to show you just how far she can pull your leg. The Texanist directs you to call malarkey on her posthaste, for this is nothing more than a big load of preposterous and bad-smelling balderdash! Texas (it goes without saying, but the Texanist is going to say it anyway) is loaded with armadillos, and among its Rio Grandes, Easterns, and Merriam’s, the Lone Star State is also teeming with toms, hens, jakes, and jennys. Missouri may have a lot of wild turkeys too, and even spotted us a few gobblers back in the nineties when we were padding our numbers, but the Texanist assures you that no armadillos changed hands as part of that transaction. The good folks over at Parks and Wildlife would never allow the use of our official state small mammal as currency. Come on! Turkeys for armadillos? What would the exchange rate be? Ask your co-worker, because the Texanist doesn’t know. This is ridiculous. Let’s see, the Texanist will trade you fifty armadillos for ten wild turkeys. Thank you. Have a nice day. Hey, wait—he found ten more dillos in the seat crack of his truck. What do you know about that? Lucky day. How about four racks of those St. Louis–style barbecued ribs, three cases of Budweiser, a couple of those Mark Twain novels, and two tickets for a paddleboat excursion down the old Mississippi? How many armadillos will that cost? Get outta here. Turkeys for armadillos. The Texanist has to go now.

The Texanist’s Little-Known Fact of the Month:

Before he ever touched a football, or earned the nickname by which he is best known, or introduced such innovations as the three-point stance, the screen pass, the spiral punt, and the naked reverse, Glenn Scobey “Pop” Warner lived on a ranch outside Wichita Falls.