The body of Tony Ayala Jr. was finally at rest, lying inside a closed metal casket at the M. E. Rodriguez Funeral Home in downtown San Antonio. On an easel to the right stood a painting of Ayala’s late father, the boxing trainer Tony Ayala Sr., surrounded by his four boxer sons—bare-chested, gloves on fists, ready for all comers. To the left of the casket was a portrait of Ayala himself, shown as he’d appeared on the cover of the December 1982 issue of The Ring, which declared him “Boxing’s Bad Boy.” At that time, Ayala, who was not yet twenty years old, had amassed a professional record of 22-0, was two months away from a fight for the WBA junior middleweight title, and seemed on the verge of superstardom.

In the pews, mourners listened as a deacon described the mysteries of Christ’s life and crucifixion, sometimes stopping to liken them obliquely to Ayala’s own struggles—his “falls with the cross,” his “moments of suffering.” After each of these meditations, the mourners would break into prayer, ending with an invocation. “Oh, my Jesus, forgive us our sins,” the room would recite in unison. “Save us from the fires of hell, lead all souls to heaven, especially those most in need of thy mercy.” And then, each time, a mariachi band, haunting and bittersweet, would play.

Two weeks earlier, on the morning of May 12, the 52-year-old Ayala had been found dead of an apparent overdose at the West Side’s Zarzamora Street Gym, which he co-owned, ending one of the most tormented lives in the history of sports. Ayala, who was nicknamed El Torito, was the fiercest fighter ever to come out of San Antonio, but he never became a world champion. Only weeks after he appeared on the cover of Ring, he raped a woman at knifepoint and went to prison. When he was released, in 1999, he returned home to admiring newspaper profiles that anticipated his “Rocky Balboa–like comeback.” But Ayala’s run at redemption soon curdled into self-destruction, and within a few years he ended up back in the penitentiary for another decade. He had been out a little more than a year when the police found his slumped body next to a syringe and a ball of heroin, lividity already setting in.

After the rosary prayers concluded at the funeral home, Ayala’s oldest brother, Mike, shuffled to the podium with a weary gait. He and his mother had spent much of the two weeks since his brother’s death engaged in a court battle with Ayala’s romantic partner, Jenna Lewis, who claims she was his common-law wife, over ownership of the gym and the right to bury his body. The dispute had added a nasty coda to what was already an awful end.

“My brother has paid for his trespasses against humanity,” Mike began, “and we apologize to the victims for what has happened. He was destined for greatness, but like all of us, he fell down, and to come back was hard. I lost my brother to addiction. I’m not making an excuse. I’m just offering an explanation. I’m just offering an explanation for what he has done.”

And with that he called a young boxer up to the podium. The child came scampering down the aisle. “My brother loved this little boy, he trained him,” Mike said, embracing the kid tightly. “There was good in my brother. My brother wasn’t a bad guy. It’s just that sometimes you get caught in different things.”

“Some people say, ‘How did the Ayalas, four brothers, three of them national champions—how could we blow it?’ ” Mike said a week before the service, as we sat at a Chili’s in South San Antonio. “But we did. Those things happen. And that bothered me. It bothers me today.”

Now an air-conditioning and heating repairman, Mike has endured his share of troubles. He was strung out on heroin when he lost his bid for the WBC featherweight title in 1979, a fight he should have won. Two years later, he almost died of hepatitis; over the next decade, he worked hard to get his life back in order.

“We grew up tough,” he said. “We were fighting grown men and we were just kids—we were young and crazy. We had a motto, ‘Beers, Brawls, and Broads,’ and we had no fear.”

The Ayalas had been fighters from birth. Tony Sr., a demanding ex-Marine, trained his sons to be champions. When they were children, the Ayala boys would appear as between-fight entertainment at professional bouts, convincing everyone that they were nascent stars. In 1973, when Mike won the Golden Gloves flyweight championship, they began to prove it. Sammy, the next oldest, won the Golden Gloves lightweight title in 1977. And two years later, Tony Jr. took home the Golden Gloves middleweight crown. (The youngest brother, Paulie, began a pro career as a featherweight in 1984.)

By the time he won that title, Tony Jr. was drinking and shooting heroin, and his violent tendencies had become impossible to overlook. In 1978, when he was fifteen years old, he’d committed a brutal sexual assault on a woman in a movie theater restroom, and he was set to be tried as an adult. Instead, the victim, who received $40,000 from the Ayalas, asked for leniency, and Tony Jr. got off with probation. “He was a phenom, and they just protected his career—even the local judges,” said John Whisler, a longtime San Antonio Express-News boxing writer.

Indeed, San Antonio had never seen anything quite like Ayala. “The Spurs weren’t that big back then; boxing was really the sport, and Ayala was just a monster attraction,” said Lester Bedford, a Texas boxing event producer who worked with Ayala. “Everywhere he fought, it was a headline story. This was a once-in-a-generation fighter, maybe a once-in-a-lifetime fighter, and it was playing out right there in San Antonio.”

Ayala had a nasty streak in the ring. He spat on one opponent after knocking him out and continued to pummel another even after the fighter was down on the floor. But Ayala was also charming and media savvy, a boxing promoter’s dream. Then, on New Year’s Day 1983, when Ayala was training for his championship fight, everything blew up. At around 5 a.m. he left his apartment, went downstairs, and broke into the home of a neighbor. He blindfolded her, tied her up, threatened to kill her, and then raped her. The police arrested him before dawn.

“I was in New York, and one of my friends called me and said, ‘Did you hear?’ ” Mike said. “It’s a feeling that I can’t describe, it’s a feeling like I feel now—like a numbness.”

Sixteen years later, when Ayala returned from prison, he seemed like a changed man, and he found a boxing world that was eager to forgive him. Bedford and his partner signed him to a $750,000 promotion deal, and Brian Raditz, his prison psychologist, became his manager. During his time in prison, Ayala had told Raditz that he had been a victim of sexual abuse as a child, and in interviews, Ayala spoke thoughtfully about its impact on him.

“My issues were that I was young, and I had been molested,” he told the Philadelphia Daily News. “I’m not saying that is why I committed the crime that put me in here. I’m not making excuses for that. I am giving an explanation for why I might have been the way I was.”

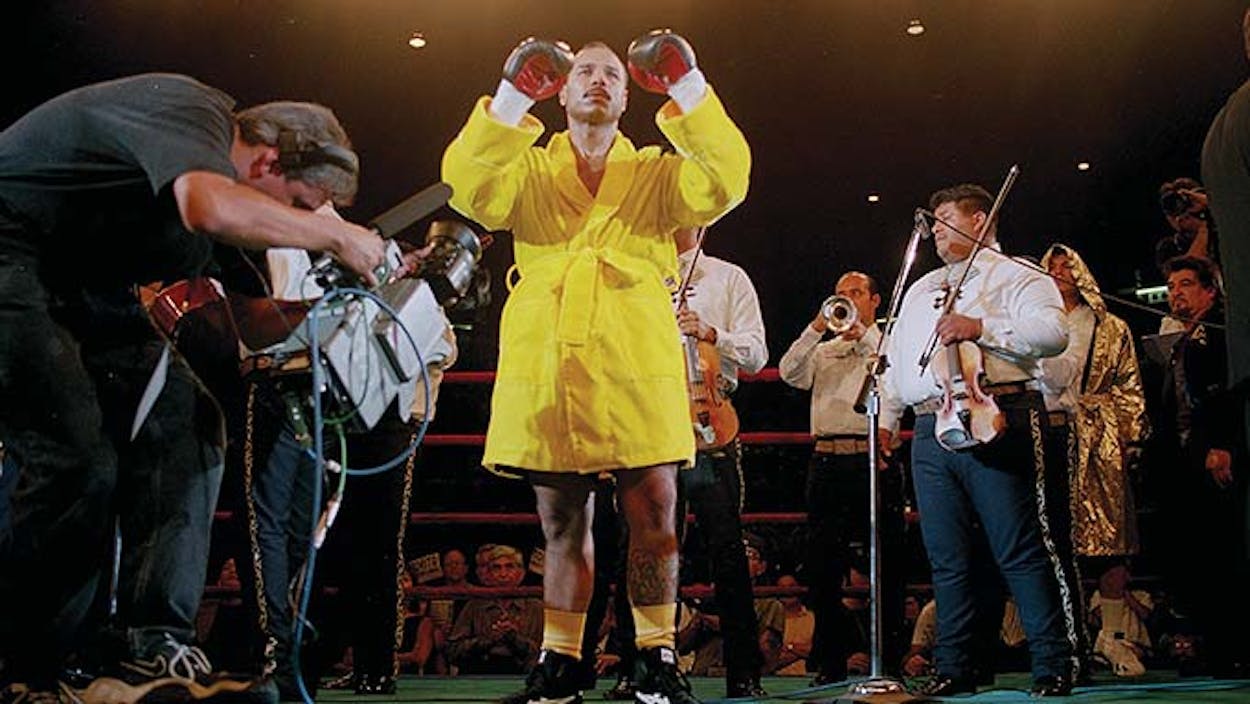

When Ayala entered San Antonio’s sold-out Freeman Coliseum on August 20, 1999, for his return to the ring, he arrived as a conquering hero. “That was the most electric entrance of a fighter that I’ve ever witnessed,” Bedford remembered. “I looked up and saw people with tears in their eyes.” Ayala finished off his opponent in the third round and went on to win his next four fights, all by knockout. It seemed only a matter of time until he would fight for a title against one of the sport’s biggest stars, Oscar De La Hoya.

The comeback was not to be. Ayala broke his hand in a fight and was forced to throw in the towel. It was the first loss of his career, and suddenly his momentum shifted. Bedford declined to pick up an option on his contract. Rumors spread that drinking and drugs were once again becoming problems, and a string of crimes—including breaking into the home of two women late at night (one of whom shot Ayala in the shoulder)—had him spending short stays in jail and barely avoiding more-serious convictions. In July 2004, a year after losing a fight to a journeyman boxer who worked as a night supervisor at Kmart, Ayala was sentenced to ten more years in prison for parole violations.

The week after Ayala’s death, I met 47-year-old former champion bantamweight fighter John Michael Johnson near his home on the South Side. Johnson had been training at Zarzamora Street Gym since his former manager, Bingo King Eddie Garcia, opened it in the late eighties, and he stayed on once Tony Sr.—his trainer and a man he viewed almost as an adoptive father—took it over a few years later. When Ayala once again returned from prison last year, Johnson was still at the gym, training for a late-career comeback of his own. Johnson had struggled with addiction and blown chances himself—he’s now sober and works as a foreman at a coal power plant—and he saw Ayala returning to a bleak situation.

Tony Sr. had died a few weeks before his son’s release, and this time around, Ayala arrived in a world that had moved on. San Antonio was now a major fight town, but many younger fans barely knew his name. There were no admiring profiles, no serious interest from boxing promoters. Ayala, now in his fifties, couldn’t get a job.

There were bright spots, though: with his brother Mike, he took over Zarzamora Street and by all accounts seemed passionate about training fighters. “He was doing what his dad did, and I saw him with a smile every day,” said Maribel Zurita, a former world champion who trained under Tony Sr.

But even his work as a trainer was deeply fraught. Last year, when he went to a national amateur tournament in Missouri, event officials told him that they would not let a convicted sex offender oversee amateur fighters. “He tried to change,” Mike said. “But how can you change your life without being given a chance?” Not long after, many of Zarzamora Street’s longtime boxers and trainers left the gym. Eventually, Mike had a falling out with his brother and departed too.

As Ayala’s world shrank, he became increasingly erratic, Johnson said. Zarzamora Street was scheduled to be open six days a week, but boxers would often show up to shuttered doors and, unable to reach Ayala, they’d leave. “Something was troubling him,” Johnson said. “I would look at him, and he’d be just pacing by himself.

“I get chills just talking about this,” Johnson continued, “but about two weeks ago I was in the dressing room, and I saw his dad in the mirror. I went and told Tony Jr., and he said, ‘You know what, man? I know he’s in here. I saw my dad the other day too.’ ”

Johnson didn’t read too much into the spectral visitation. Ayala had been getting back into shape, contemplating a few final fights, and looking forward to taking one of his boxers to a title bout. In fact, on the last day of Ayala’s life, Johnson had seen plenty of reasons for hope. Major fights tend to spike boxing gym attendance, and the recent Manny Pacquiao–Floyd Mayweather bout had brought new faces to Zarzamora Street. On that Monday, the gym was packed, Johnson remembered. “There were eight new people, and I said, ‘Tony, you got a good crowd now—don’t screw it up.’ ”

That night, Ayala and Lewis drove back to her house in the Hill Country town of Center Point and got into an argument. As he had many times before, Ayala fled, driving back to Zarzamora Street. That was the last time anyone saw him.

“I’ve been talking to some fighters from the gym,” Johnson said, “and from around one-thirty to three-thirty that morning, Tony called six different people. Why? He had to be reaching out. He needed to talk to somebody.”

We’ll never know what, exactly, he would have said. None of the fighters he tried to reach picked up the phone.

- More About:

- Sports