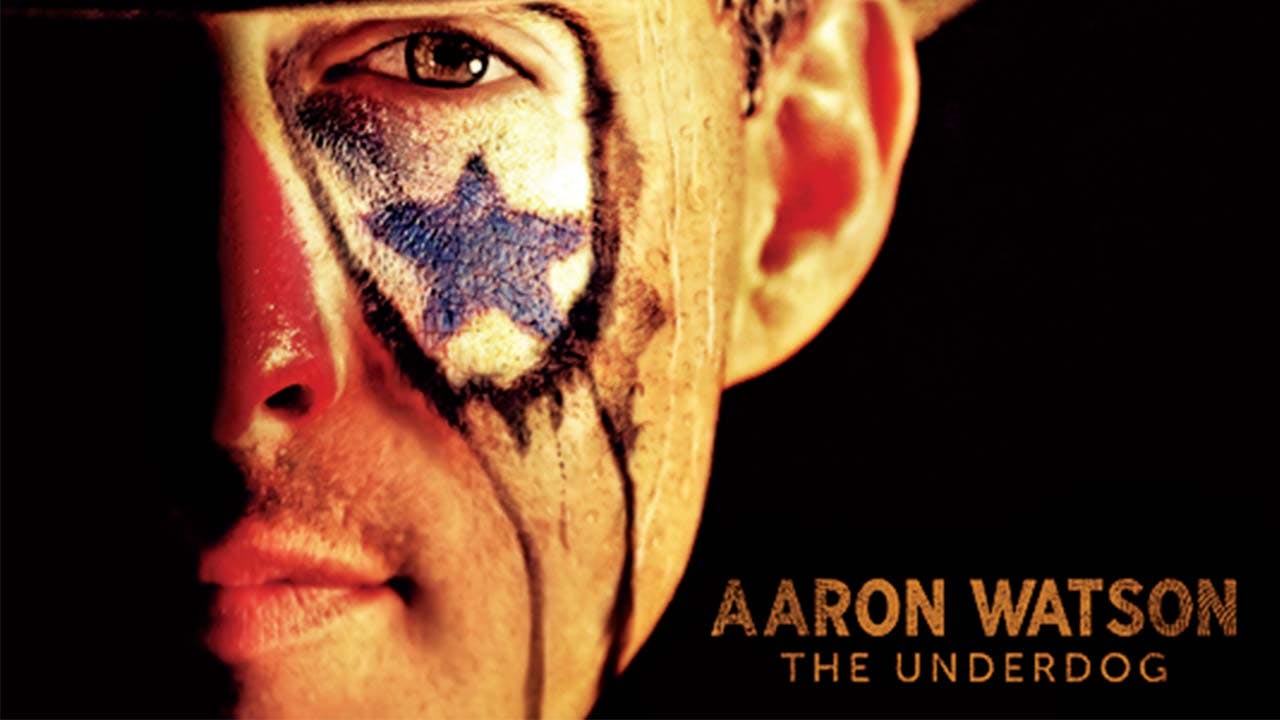

It’s a miserable night in Columbus, Ohio. The temperature is hovering just above freezing, and a bone-soaking rain falls continuously. College students are going out for the first Saturday night of the spring semester, emerging from stately brick houses and old shiplap homes, and congregating in loud masses at the bars and nightclubs along High Street across from the Ohio State University campus. The street food vendors are heating up their flattops, and cabs are beginning to flip on their lights. Meanwhile, seemingly every Stetson wearer in central Ohio is heading to the Newport Music Hall to see Aaron Watson, the latest country music phenomenon to emerge from the Texas Panhandle—and an upstart one at that. His 2015 album debuted at number one on the Billboard Top Country Albums chart; he’s the first male country singer to have a number one record without a major label. The album is titled, appropriately enough, The Underdog. For years, Watson had been turned away by Nashville recording executives, who all said he’d have to change his sound if he ever wanted to succeed outside Texas. And yet here he is, with a number one album to his name, about to play to a packed house on a cold, wet night in the Midwest.

Before the show, Watson lounges in the back of his tour bus, his boots up on a seat, a grapefruit LaCroix in hand, ball cap askew because of his propensity to pull it off and rub his head while he talks. He’s relaxed. He’s not worried whether he plays tonight for two thousand or twenty; he just wants to play a good show, and if he does, he knows the word will spread. “Whoever shows up tonight,” he says, “they’re gonna go home and they’re gonna tweet, they’re gonna Instagram, they’re gonna Facebook: ‘Man, we had a blast at the Aaron Watson show tonight, and he hung out with us afterward.’ ” He remembers a show, years ago, in Ardmore, Oklahoma. He was about to hit the stage, and he texted his friend, business partner, and manager Gino Genaro: “What if no one shows up?” Genaro thought Watson was just having preshow jitters and tried to encourage him. But Watson wasn’t kidding. That night, only one person showed up. Rather than play to her in an empty theater, they walked her to the bus, climbed aboard, and played a private acoustic set. Doesn’t matter how many show up, he says, always give them your best.

There may be no more genuine singer-songwriter at the moment than Watson. He leaves no confusion about who he is: He loves Texas. He’s a man of the cloth—denim—spreading the 5X-beaver-felt-and-barbed-wire gospel to the world. He likes writing songs about two-steppin’ and wholesome good times, and he’s not going to abandon that ethos for any quick shot at stardom by betraying his fans and deviating from his brand of country music. He didn’t do it at 24, even when the music executives told him what it would take to be a star: sign on the line, agree to the terms, and we’ll put the Nashville machine to work for you. Watson didn’t want to achieve success that way—stardom isn’t what he’s after, anyway—so Nashville wished him good luck and sent him on his way back to Texas.

For the past eighteen years, he’s picked away at his craft, recording albums at a furious pace—thirteen so far—on which he’s written nearly all the songs. In that time, he’s played 2,500 shows. On most days, he rises at 5 a.m. to write. He stays hours after performances to talk to every lingering fan. In short, he works like it’s his job. “We work hard, and we ride a horse named Hustle,” he says. When he discusses artists he admires, he often talks about their journeyman years. It’s about putting in the effort, appreciating steady growth, and always making fans feel like part of the family. Meanwhile, his aim is to keep plugging away, keep building, have faith, and when he meets with success, try not to let it go to his head. So far, so good.

The vibe on the tour bus, as the freezing drizzle outside begins to pick up, can best be described as friendly and professional. The small traveling team that runs Aaron Watson the brand has been together for close to a decade, some for nearly fifteen years. While they prepare for the show, the lighting tech, sound guy, musicians, and manager chat, tell jokes, and watch football. They’re happy to have the submarinelike bunks crammed into the 45-by-9-foot tour bus. After all, it’s better than the Ford Excursion they took to their early gigs together, in tiny venues that paid a total of $250. They’ve come a long way since then. When he leaves Columbus in the morning, Watson will head back to Texas to prepare for his ninth European tour.

The tour follows the February release of Vaquero—his first album in the post-Underdog era. It is a hair poppier than previous offerings. When the single “Outta Style” came out ahead of the album release, it caused a bit of a stir. What, some fans wondered, were these handclaps? And that driving electric guitar? Was Aaron—gulp—going Nashville? Kyle Coroneos wrote on the site SavingCountryMusic.com that he wasn’t all that impressed. “Shades of Bro-Country,” he wrote. But he wasn’t too worried. “Maybe it’s the fact that the fiddle is so out front that you forgive some of the other stuff, or maybe because Aaron Watson is a natural underdog, you want to root for him.”

His fans in Ohio don’t seem concerned. Minutes before the show, they’re packed in, pushing closer to the stage. The lights start to swirl, and the crowd is screaming like it’s an Ohio State home opener before Watson, who has made his way in from the tour bus, even sets his Tony Lama boots on stage. When he does, a man in the crowd, dressed like a Cavender’s catalog model, lets out an ear-splitting war whoop and lifts a Coors Light high above his black cowboy hat. Three songs in, everyone in the place—families with kids, college students on dates, gently swaying married couples—is singing along to a song about bluebonnets in spring. An Aaron Watson tune is solid, sturdy, well crafted, dependable. He riffs on the familiar, weaves in wordplay and funny twists like George Strait. Above all, he is authentic. What you see is what you get. At a time when everyone and everything seems overly marketed, when we’re being constantly manipulated and sold to, the music of Aaron Watson can be awfully appealing. There’s no gimmick, no pretension, there’s certainly no irony. The notes may sometimes feel predictable, but boy, if they don’t make you feel good. When the bluebonnet song ends, Watson tells the crowd: “We’re gonna play some good old country music tonight!” And the place goes wild.

Watson grew up in Amarillo, the son of Ken, a veteran injured in Vietnam, and Andra, who always made sure Aaron sang loudly at their little Church of Christ, where musical instruments weren’t allowed and every bad note sung could be clearly heard. He speaks reverently not only of those timeworn church hymns but of his father’s extensive vinyl collection. By age four, he was learning from his dad how to gingerly remove records from their sleeves, hold them ever so lightly with the palms, and lower them onto the turntable so as not to scuff, scratch, or smudge them. There were Willie and Waylon in the house, of course, but there were also the Beatles and the Rolling Stones. “Whether it was at church, or whether it was at home, the music my mom and dad surrounded me with was pure heart and soul,” he says in that flat, nasal twang of the Panhandle. “And it had a huge impact on the artist I am today.”

He learned his work ethic at a young age. He remembers one day in particular as “a defining moment in my life.” It was a jeans-stick-to-your-thighs hot day in Amarillo, and a ten-year-old Aaron was on his hands and knees scrubbing toilets on a job with his dad. Across the street, his friends were swimming. Watson was decked out in yellow rubber gloves, working away, hating every minute of it, like anyone his age would. He jawed and complained, said he wanted to go swimming with his buddies. His father, polishing away in the stall next to Aaron, sat up on his knees and looked around the divider into the stall his son was cleaning.

“Son,” he asked, “do you think your daddy wants to be cleaning toilets?” But that’s how he took care of his family. God blessed him with that job, his father said, so he did it the very best he could. “My dad’s goal in life is bigger than country music,” Aaron says. “My dad’s goal in life was to work hard, make an honest living, and love his family. What’s better than that?” He thinks it’s funny when people praise him for spending so much time with his fans after the show. It’s a heck of a lot easier than scrubbing toilets.

As a boy, he also threw himself into baseball, dreaming of playing shortstop for the Houston Astros. He played in high school and later made the roster of the New Mexico Junior College Thunderbirds, in Hobbs, just across the border. He didn’t think of baseball as a hotbed of life lessons at the time, but now he looks back and says that it shaped him, shaped his drive and his humility. “You win some, you lose some, but day in, day out, you give your best.” And those are lessons he’s trying to pass on now that he and his wife, Kimberly, have kids. His two young boys, Jake and Jack, play ball too. When he talks about their games, he gets animated, sits up, starts laying out strategy. To his boys, he emphasizes one thing: “Get up to the plate, and give it all you’ve got.” It doesn’t matter if the other team has some thirteen-year-old who can throw 70 miles per hour. You can’t get a hit if you don’t swing.

“Everybody said you’d never make it too far,” Watson sings on his latest single, “with some poor boy playing on some pawnshop guitar.” At eighteen, Watson, having saved up some money mowing lawns, walked into a pawnshop and bought a guitar. He wanted to start learning how to turn the lyrics bouncing around his head into music, to “put chords to it,” he says. It’s the guitar he still writes songs with. The timing was right because, later that fall, a back injury forced him out of baseball, and he became more serious about music.

After he left Hobbs, he enrolled at Abilene Christian University, where he took an introduction to guitar course. It was taught by Dan Mitchell, a local musician who’s taught guitar for more than three decades and who Watson affectionately calls “Dr. Mitchell,” though he has no doctoral degree. At Watson’s first lesson, Mitchell asked why he wanted to learn guitar. Watson said he wanted to be a singer-songwriter. “Well,” Mitchell said, “let’s get to work.”

One afternoon, Watson was sitting in a diner in downtown Abilene eating lunch with a friend. As he dipped his spoon into a bowl of gumbo, a pair of electric-blue, full-quill ostrich boots came through the door. Watson’s eyes lit up big as saucers. The man walked up to the counter and ordered something Watson had never heard of: a cappuccino. After getting his drink, he walked over to Watson, who had been staring. What are you looking at, kid? the man asked. Nothing, Mr. Gatlin, Watson responded. Larry Gatlin, the falsetto voice of more than 30 Top 40 country singles, was impressed that this college student recognized him and sat down in the booth. Watson proceeded, as politely as possible, to interrogate Gatlin about his career and his songwriting. As their conversation wrapped up, Watson’s friend chimed in. You should hear Aaron sing, she told Gatlin. He’s got a good voice, she said, and he’s a songwriter.

“I just remember looking at her like, ‘I cannot believe you just said that.’ ” But he forgives her, he says. She’s a California city girl—how could she have known that this man had written songs for Elvis?

Gatlin was annoyed Watson’s songwriting hadn’t been brought up earlier. He was playing a show that night at the Abilene Civic Center. He’d leave tickets at the box office for Watson, who should arrive an hour before the show. The meeting was fortuitous for both men. Watson would gain a songwriting mentor. And Gatlin had forgotten his wallet, so Watson covered his cappuccino.

That night Watson showed up early, and Gatlin pulled him backstage. Before he went on, Gatlin passed on some songwriting wisdom he’d gotten from his friend, Kris Kristofferson. “Write a thousand songs,” Gatlin said, “then throw them away. After that, you’ll be a songwriter.”

They stayed in touch over the next year, as Watson began to gather song ideas. He started writing in earnest, sending cassette tapes to Gatlin for advice. Over the years, Gatlin had gleaned wisdom not only from Kristofferson, but Willie and Johnny Cash too. Now he was imparting it to Watson, one unapologetic critique at a time. “He ripped me good,” Watson says with a grin. (They would share a bill years later when Watson made his Grand Ole Opry debut in Nashville. He’d be pretty nervous before that one.)

In 1999, with Gatlin’s advice still fresh in his mind, he released his first album, Singer/Songwriter. He sold copies of the album out of his backpack, but it never reached the radio.

But his third album, Shut Up and Dance, released in 2002, received a lot of regional airplay. That got his career rolling. Watson started packing bars and dance halls across the state and soon drew the attention of a few major labels in Nashville. One label told him he’d have to change his sound and relocate to Music City. Another informed Watson he’d just be a regional act. At best. “I was heartbroke,” he admits. “A little shattered.” He drove home. His dad responded coolly that this was the same thing they told Willie for all those years, “and he finally made it at about 45 years old.” Indeed, Red Headed Stranger, which vaulted the outlaw to stardom, was released in 1975, when Willie was 42. To a 24-year-old, this was astounding. Aaron said, “You mean I’ll have to do this for another twenty years before I make it?”

“Yeah,” his dad said. “If you want it bad enough.”

There’s something about Watson, something in his friendly, straightforward demeanor, his way of seeming interested in everyone who’s interested in him, that defies music industry stereotypes. Watson himself likes to compare his music making to a family business—like, say, a hamburger joint.

“What do you want when you go in?” Watson says as he sits up straight, pulls down his ball cap, sticks his hand out, and begins enumerating on each finger. “You want a nice environment, you want good service and a delicious burger. And maybe buttermilk pie for dessert. With coffee.” Deliver a good product, and people will keep coming back. “My fans, they don’t want to hear somebody else’s songs. They want to hear what I have to say.”

“It’s the heart of Texans,” club manager Concho Minick says of Watson’s music. “He’s entrepreneurial, he’s authentic.” Minick is the president of Billy Bob’s Texas, the 127,000-square-foot Fort Worth Stockyards institution and self-proclaimed largest honky-tonk in the world. The building, which at various times had been a cattle barn, aircraft manufacturing plant, and department store, opened as a music venue in 1981. Its opening act was Larry Gatlin. Since then, just about everyone of note in the country music world has passed through. But when Minick was organizing a Billy Bob’s–branded music festival in Italy last year, he chose Watson as his headliner and ambassador. With nineteen shows on the books, Watson is a Billy Bob’s favorite. He brings in the kind of people Minick thinks exemplify the place.

“If you drew up who you wanted to see in Billy Bob’s on Friday or Saturday night, that’s it,” he says. “These are the people you see at church, or the corner store, or out with your hunting buddies.” Over the years, he’s seen the evolution of Aaron Watson into an emerging star, from the self-described Honky Tonk Kid (the title of Watson’s 2004 album) to the Underdog and, now, the Vaquero. That success isn’t a surprise to Minick. He remembers Watson packing three thousand into Billy Bob’s back in 2010. He says Watson might soon be too big to play Billy Bob’s. “That time’s probably coming for Aaron, and we’ll be happy to be part of his rise. I’m happy to see it. I really am.”

For Minick, it’s hard not to root for Watson. Since he took over as the president of Billy Bob’s from his father in 2011, Minick has presided over seven hundred country music shows. In that time, he’s received exactly two Christmas cards from performers. One was from Aaron Watson. And it wasn’t just a generic greeting sent to a perfunctory list of associates; it was a genuine Christmas card from Aaron, Kimberly, and the kids.

That kind of personal touch has helped fuel Watson’s career, and it’s an approach that jibes with major changes in the industry. The rise of streaming music and social media has altered the fan relationship with the artist. People don’t have to let the radio or the record store determine what they have access to anymore. Not only can fans buy their music directly from the source but now they can talk right back to the musician, and Watson embraces it. His fans know his family. They keep up with the boys’ baseball games and haircuts on Instagram. They point out their favorite songs on YouTube—the comments are remarkably ebullient and notably personal—and Watson and Genaro pay attention. Watson can recite fans’ social media posts off the top of his head, like the man who said he’d raised his sons to Watson music and just wanted to say thanks. Watson reads them partly because he cares and partly because he wants to build and keep a loyal following and not be just a flash in the pan.

Seven of his albums were produced by Ray Benson, of Asleep at the Wheel. In terms of old-school Texas credibility, that kind of pedigree would be hard to beat. Unless, of course, you add Willie. While working on The Honky Tonk Kid, Benson went over to Nelson’s house to shoot some pool. He put an early cut of the album on the sound system as they played, and Willie asked to listen to it again. And again. If you like it so much, Benson offered, how about you play on the album? That’s how Watson got to work with the voice that shaped his childhood, with Willie chiming in on the album’s title track: “Thirstin’ for knowledge, all hungry and green / Strummin’ that six-string, just like Lefty did / Everybody loves the Honky Tonk Kid.”

By 2005, things were going well, and Aaron and Kimberly started having kids: first Jake, then Jack, then Jolee Kate. They wanted four, and soon Kimberly was expecting again. One day in early 2011, they met with doctors to find out the sex of their fourth child. It was a girl, they were told, but there was something else. She would be born with a genetic defect called trisomy 18. Also known as Edwards syndrome, it meant that she would be born small and likely with severe disabilities that, according to doctors, were incompatible with life. Aaron and Kimberly weren’t going to end the pregnancy. It was their baby, no matter what happened.

Julia Grace Watson was born prematurely on October 10, 2011. The kids were with them, and the Watsons stayed with Julia for the few hours that she lived. As Julia slipped away, Aaron sang “Blue Skies and Rainbows” and “Jesus Loves the Little Children.”

It wasn’t easy getting back to work after that, especially for a record called Real Good Time. Somewhere, Watson came across a quote from the mother of Lane Frost, a bull rider killed at the 1989 Cheyenne Frontier Days rodeo. It was an expression that the Frosts put on Lane’s tombstone: “Lane wasn’t perfect but he knew Jesus.” Something, Watson says, opened up his heart when he heard that. A burden was lifted. He remembered his faith, remembered that all his work, all the tragedy, was in service of something bigger and better. He wrote a song for Lane’s parents. He had no plans to release it, but a year later, Watson played the song for them in person at the National Finals Rodeo in Las Vegas. The song became an immediate fan favorite, and Watson eventually decided to release it. “July in Cheyenne (Song for Lane’s Momma)” topped the Texas charts and won song and video of the year at the Texas Regional Radio Music Awards. The album debuted in October 2012 at number nine on the Billboard country charts—Watson’s best showing yet.

Nashville had slammed doors in his face, told him to tweak this, to change that, and Watson was still going, more than a decade in, without changing and without a major label. Now persistence wasn’t just a requirement; it was becoming part of his brand. Loyal crowds at rodeos kept coming, kept telling friends to come, and kept up with Watson at each stop. He was honing his craft, writing more songs—sometimes pulling over on the side of the road to do so—and keeping his fans happy. Whole families were listening to him. Kids were growing up with his music. One fan recently sent him a message on social media, when he announced he’d be opening this month’s Houston Rodeo. It was a picture of Watson with a little boy, all duded up as a cowboy. This is you and my son, the fan wrote. He’s a teenager now, and we’re going to see you in Houston. Another fan commented that her husband heard the news about Houston and remarked: “You know, Aaron Watson reminds me that sometimes good things happen to good people who work hard.”

One morning in February 2015, he was sitting at his kitchen table after he’d dropped his kids off at school. He was chatting with Kimberly, who was scrambling eggs, when his manager called. “Are you sitting down?” Genaro said. “You did it.” His album, The Underdog, had just debuted at number one on the Billboard country charts, making him the first independent male artist to do so. “We jumped up and down, dancing around like kids,” Watson says.

The experiment had worked. In the twenty-first century, a regional artist can also be a global one. Being unapologetically Texan isn’t an impediment anymore. Because, Watson believes, there’s something relatable about having pride in where you’re from and something timeless in the image of a cowboy. “James Dean on the set of Giant in Marfa, Texas, would look just as GQ in 2017 as he did in 1956. It’s just a fact,” Watson says, sitting on his bus. “There’s nothing more classic than a nice pair of boots, worn-out jeans, a white pearl-snap, and,” he plucks a hat off the wall, “the Resistol hat.”

“I’m proud to be from Texas,” he says with a little fire behind his eyes. “Are you crazy? When I hear people in Nashville tell me I need to get away from that, I just say ‘whatever.’ Didn’t Davy Crockett come here from Tennessee?”

With The Underdog, its cover image of a sweaty Watson made up like a rodeo clown, the cowboy had won his buckle. After the initial excitement, reality set in. After sixteen years, he was now an acclaimed up-and-comer, and he felt he had to work even harder. For years, he’d been a draw on the rodeo circuit, a “dance hall and county fair act,” as Genaro put it, but this was something else entirely. He was now the symbol of a new path to success in country music. The album got its own display at the Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum (in Nashville, naturally). For the past two years, signs at his concerts have been emblazoned in hunter’s orange with the message: “Always believe in the Underdog.”

The album’s success was thrilling. “But it really made me go, ‘Whoa. We’re gonna be here for a minute,’ ” Genaro says. Now he and Watson are thinking about what happens five years down the road and further. Watson recently realized that he’s probably written his first thousand songs. He’s glad he didn’t throw them all out. A few of them were pretty good, and he feels like he’s still improving. “I really believe I’m just catching my stride as a songwriter.”

Genaro has been with Watson for fifteen years, and lately they’ve been thinking about his legacy. In about a decade, when Watson’s kids walk into their first college dorm rooms and tell their roommates that their father is Aaron Watson, country musician, what will the response be? “Oh yeah, I heard him on the radio”? Or, “Oh yeah, his songs really mean a lot to me”? Watson knows what he’d prefer. So before every show, as the nerves creep in, he says a prayer. He asks that he put on a good show. He asks that he bring his fans joy. “Especially these young kids. They’ve been following me for such a long time. They look up to me, and that’s something you should take seriously.

“God’s blessed me with the opportunity to do what I love and the platform to have a positive influence on those around me,” he says.

The show in Columbus has been over for something like two hours. Men with push brooms are sweeping up 32-ounce beer cups from the emptied-out dance floor, leaving a sticky trail that glistens under the house lights. It’s edging toward 12:30 on Sunday morning, and Watson is still standing in front of his merchandise table. There’s one last fan who has patiently waited out an autograph line that had snaked up a set of stairs and deep into the balcony. He’s sporting a jet-black cowboy hat and a puffy Carhartt jacket, and by the looks of him, he doesn’t have a driver’s license yet. Just a honky-tonk kid. He’s telling Watson that he wants to write songs. He’s asking for advice. Write, write, write, Watson tells him. And he passes along some songwriting wisdom that had once been given to him. “Write a thousand songs, then throw them away,” he says. “Then you’ll be a songwriter. When you’ve got something, send it to me. I’ll give it a listen.” And the young man didn’t even have to buy Watson a cappuccino. God-bless-yous are exchanged along with a firm handshake. Then Aaron Watson heads off to hit the road again.

Andrew Roush, a Bastrop native, is a senior editor at New Mexico Magazine. He lives in Santa Fe.