On the Gulf of Mexico in the first half of the sixteenth century lived a people who came to be known as the Karankawas. They were divided into five bands spread out along the margins of the Texas coast. Karankawas moved with the seasons. They spent the summers hunting and harvesting on the mainland prairies, and in the fall and winter they set up camp along the bay shores or paddled their dugout canoes across the lagoons to the string of low-lying barrier islands that protected the inland waters from the open gulf. They moved seaward to take advantage of the spawning seasons of drum and redfish and speckled trout, catching the fish in weirs and nets or through deadly accurate use of their distinctively long bows. Karankawas were famously tall; everyone who encountered them remarked on it. They were tattooed and mostly naked, their lower lips sometimes pierced with short lengths of cane, their skin glistening with the alligator grease they employed to ward off mosquitoes. They made pottery and painted designs on it with black beach tar. They lived in willow-framed huts that could be gathered up and moved quickly as they followed the food sources season to season.

On a freezing November day in 1528, on some narrow, windswept stretch of—or near—Galveston Island, a hunting party of three Karankawa men encountered a shocking apparition. It was a man, or at least something like a man, carrying a pot he had stolen from their village while all the people were away. He had taken some fish as well, and was either carrying or being followed by one of the village dogs. The stranger was starving and haggard. His skin was oddly pale, his hair and beard matted. His emaciated body shivered beneath the few loose rags that covered it. He looked back at the Karankawas but ignored their attempts to communicate with him and kept walking toward the desolate ocean beach. When he reached it, the Karankawas held back a little, staring in amazement. There were forty other men there, sprawled in the sand around a driftwood fire. Near them, half-buried in the sand where it had been violently driven in by the waves, was some sort of crude vessel, a thirty-foot-long raft of lashed pine logs, with a rough-hewn mast and spars and a disintegrating sail made out of sewn-together shirts.

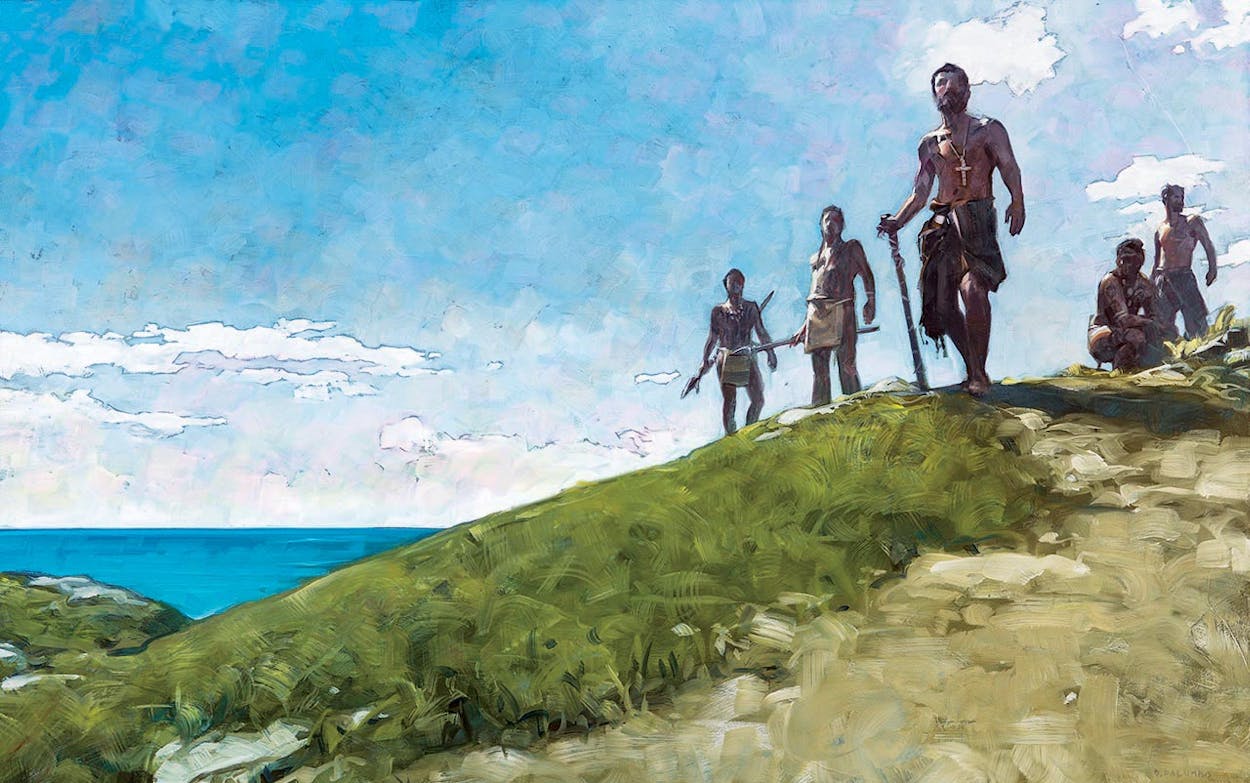

Within half an hour, a hundred or so Karankawa warriors had arrived to gawk at the castaways. They did not seem to be a threat, since they had no weapons and most of them were too weak to stand. Finally, two of the men rose from the sand and staggered over to the Indians. The one who seemed to be the leader did his best to communicate by signs that they meant no harm, and he presented them with trading goods, some beads and bells that had somehow survived as cargo during whatever disastrous voyage had just taken place.

The Karankawas made signs that they intended to return the next morning with food. They made good on their promise, bringing fish and cattail roots, and kept coming back to feed the men for several days. One evening they returned to find the strange visitors in even more desperate shape. During the day they had tried to resume their ocean journey, digging their raft out of the sand, stowing their clothes on board, and paddling out toward the gulf. Not far from shore, they had been hit by a wave, and the raft had capsized and been pounded apart against the sandbars that run parallel to the Texas shoreline. Three men had drowned, and the survivors were all now naked and so close to death from exposure that the Karankawas broke out into loud ritualistic lamentations. Then, realizing that the men would not survive the night, they got to work, some of them running off to build a series of bonfires to warm the castaways en route to their villages, others bodily picking up the starving, freezing men and carrying them to shelter.

The Karankawas were not a maritime people. They probed the bays and lagoons and paddled back and forth from the mainland to the barrier islands, but the Gulf of Mexico remained a mysterious immensity beyond the reach of their dugout canoes. And far to the east, beyond the straits of Florida, there was a much greater sea of whose existence they might have heard through unreliable stories passed along by other tribes. It was from the far side of this unknown ocean that the ghostlike men had come. They were adventurers from Spain, part of a great wave of expansion and exploration generated by the completion of a struggle that had lasted seven centuries, the Christian reconquest of the Muslim-dominated Iberian Peninsula. By 1492, King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella, whose marriage had allied the Catholic kingdoms of Aragon and Castile, had conquered Granada, the last stronghold of Al-Andalus, the name by which Muslim Spain had long been known. That same year, they financed Columbus’s first voyage of discovery, and his landfall in the West Indies gave Spain a new horizon toward which to direct its surging national confidence, and a new world to exploit.

The men who had washed up naked on this forsaken beach were, in all likelihood, the first Europeans ever to set foot in Texas. (A Spanish expedition led by Alonso Álvarez de Pineda had sailed along this coast in 1519, and had drawn a map of it, but there is no record of the explorers going ashore.) They came 36 years after Columbus, when the Spanish colonization and conquest of the Caribbean basin and of Mexico was well under way, and when the invasion of the Inca empire in Peru was about to begin. The doorway to two great continents had been breached, and it was crowded with men of rampant ambition trying to beat one another through it. Some of these men were adelantados, licensed by the Crown to risk their own fortunes in order to find and subjugate new lands. If successful, if their ships didn’t go down in a hurricane or run aground against uncharted shoals, if they didn’t starve or die of disease or get killed by the native inhabitants they had come to conquer, they would be granted titles and far-reaching administrative powers and inexhaustible wealth.

Others, like Hernán Cortés, made up in bravado what they lacked in official sanction. In 1518 Cortés was commissioned by Diego Velázquez, the governor of Cuba, to explore the newly discovered coast of Yucatán, from which two previous expeditions had returned with reports of sophisticated cities with towering stone temples and a casual abundance of gold. But Velázquez had never really trusted Cortés, and as he began to suspect his commander of being a competitor and not a subordinate partner, he withdrew the commission and even ordered his arrest. But Cortés was too fast and too crafty, and the order came too late. By February of 1519, his fleet of eleven ships had already sailed, heading westward across the Yucatán channel toward the Mexican Gulf Coast. There Cortés and his men encountered the unimaginable and proceeded to accomplish the unthinkable. Tenochtitlán, the capital of the Aztec empire, was as proud and populous as any city in Europe. To the Spaniards who beheld it after fighting their way inland from the coast, it was a sprawling, glittering, dreamlike metropolis, a place whose temple pyramids and strange sculptures and frescoes were startling in their alien beauty, and whose culture of human sacrifice—of ripped-out hearts and priests with blood-caked hair—struck their fervently Catholic minds as a devil’s pageant of horror. In only a little over two years, with a fighting force that began with fewer than six hundred men and sixteen horses but that was exponentially increased by Cortés’s dynamic diplomacy among subjugated tribes primed to rebel against Aztec domination, the Spaniards had conquered Tenochtitlán and begun the work of tearing down its temples, determined to erase this wondrous abomination of a city from human memory.

There was no Aztec grandeur on the Texas coast, a thousand miles north of Tenochtitlán, where the Karankawa bands pieced together a subsistence existence following the cycles of spawning fish and ripening fruits and nuts. And they could hardly have considered the desperate wraiths they had taken into their village as conquerors. Unlike Cortés, these Spaniards had no ships, no armor, no weapons, no intimidating beasts like the never-before-seen horses. But a year and a half earlier, these men had sailed pridefully out of Seville and down the Guadalquivir River into the open Atlantic, part of an expedition made up of five ships and six hundred people. The expedition had a grant from King Ferdinand’s grandson Charles, now King of Spain and Holy Roman Emperor, to conquer and populate all the land from the northern border of Cortés’s Mexican possessions to the Florida peninsula.

The voyage was led by a ruthless soldier and tireless schemer named Pánfilo de Narváez. Narváez had been Diego Velázquez’s sword arm in the conquest of Cuba, where he watched impassively from horseback as his men butchered the inhabitants of a village on the Caonao River. In 1520 Velázquez, still fuming over Cortés’s usurpation of his Yucatán mission, put together a powerful fleet of nineteen ships to intercept Cortés, throw him in irons, and neutralize any claim he tried to make for the plundered wealth of Mexico. Narváez, who had served Velázquez so cruelly well in Cuba, commanded the expedition. When Narváez’s armada landed, Cortés had already entered Tenochtitlán, where, in an unnervingly brazen stroke, he had taken the Aztec leader Moctezuma hostage in his own palace. Even though his position was exquisitely vulnerable, he left several hundred men behind in the city and marched the rest of his army to the coast. Cortés swiftly outwitted and outfought Narváez, peeling away some of his officers with bribes and overpowering his force in a surprise nighttime attack. Narváez lost an eye in the fight and spent two and a half years in a fetid dungeon while Cortés finished conquering Mexico with the help of the soldiers Narváez had brought to arrest him.

But Narváez’s career still held an even more disastrous third act. Once he was released from prison, he sailed to Spain, where he spent five years lobbying Charles V and the Council of the Indies for permission to “explore, conquer, populate, and discover all there is to be found of Florida.” The name “Florida” at that time meant the entire sweeping coastline of the Gulf of Mexico from Mexico’s Río de las Palmas to the Florida Keys. In 1527 Narváez’s petition to become an adelantado was finally granted, and he set out across the Atlantic with five ships bearing six hundred men and women—soldiers, colonists, slaves, and priests—to claim and somehow try to possess an unknown part of the world that was four times larger than Spain itself.

The fleet stopped in Cuba, where a hurricane destroyed one of Narváez’s ships and drowned sixty men, and where the surviving vessels ran aground onto shoals and encountered more storms once they were under sail again. But the hard luck had barely started. From Havana, Narváez sailed due west for the Río de las Palmas, on the central coast of Mexico, which was the western boundary of his vast territorial claim. He never reached it. After a month at sea, caught up in the fast-moving swirl of the Gulf Stream, which turned out to be bearing the ships in the opposite direction, and with food running low and horses dying in the holds, the fleet made landfall on the western coast of Florida, all the way across the Gulf of Mexico from its planned landing site.

Even though they were 1,500 miles away from the Río de las Palmas, the thoroughly disoriented Spaniards still thought they had nearly reached their destination. They encountered Indians who encouraged them to believe that there was a kingdom, full of gold, not far to the west. Narváez decided to reconnoiter on land, taking 300 men and sending the rest of the expedition ahead on the ships to wait for them farther up the coast. The two parts of the divided expedition never saw each other again. Narváez and his land party spent four months wandering lost and starving through nearly impassable swamps and forests, blundering into sieges and skirmishes with the native inhabitants. Desperate and unable to find the ships with which they were supposed to rendezvous, they killed and ate their horses, and set about the almost impossible task of building five seaworthy vessels that would allow them to set sail again for the Río de las Palmas. They still believed the river lay somewhere just along the coast, and once they found it, they could make their way to Pánuco, Mexico’s northernmost Spanish settlement. The 250 men who were left—50 had drowned or died of disease or starvation—constructed a crude forge and melted down their crossbows and stirrups in order to make axes to chop down trees and nails to hold their wooden rafts together.

The men were at sea on their rafts for a month and a half. They sailed westward along the Florida Panhandle, then across the mouth of the Mississippi. They were nearly dead from dehydration when the rafts finally drifted apart, strung out along the length of the Texas coast. Most of the men made it to shore somewhere. But Pánfilo de Narváez, the adelantado whose claim to all the lands of Florida was now a pathetic presumption, was last seen drifting out into the Gulf on his raft.

As the men who had been taken into the Karankawa village on Galveston Island began to revive somewhat around the fire pits, watching the Karankawas dance all night in a frighteningly ambiguous celebration, they grew alarmed. In the months since leaving Cuba, they had encountered numerous native peoples whose reaction to their presence had been mercurial, unreadable, and often violent. And they had heard the stories of what had befallen other Spaniards in Mexico, men who had been captured and sacrificed to alien gods, then flayed so thoroughly and expertly that their comrades, finding their skins strung up on temple walls, were still able to recognize their boneless, bearded faces. They were convinced that something similar was in store for them. But as the days passed, the Karankawas continued to treat them as unfortunate refugees and not as captives to be sacrificed.

The leader of the Spaniards, the man who had approached the Karankawas on the beach, asking for help and offering trade goods, was Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca. He was probably in his mid-thirties, from a distinguished family with ties to the royal court. He had been a functionary in the houses of Andalusian dukes when he was younger but had spent most of his career as a soldier, fighting the French at the Battle of Ravenna and insurrectionists in Castile. On Narváez’s expedition, he was the royal treasurer, whose mission was to ensure that the Crown received its share of any New World wealth.

But there was no longer any need for wealth to be accounted for, and only a very slim possibility of surviving. Two of the five rafts had drifted well south of the island that Cabeza de Vaca and his companions came to call Malhado—“ill fortune”—and the men on those rafts were either killed outright by Indians or died of starvation and exposure. Two other rafts had landed east of Cabeza de Vaca on Malhado, bringing the total number of survivors on the island to eighty or so. But most of the men were too sick or malnourished to survive, and within weeks only sixteen were left. Five of the Spaniards from Cabeza de Vaca’s raft had stayed behind on the beach rather than face the horrors they imagined waiting for them in the village. Starving there, they quickly turned to cannibalism. When the Indians discovered this, the relationship between the castaways and their hosts quickly began to deteriorate. The Karankawas appear to have practiced ritualistic cannibalism against their enemies, but they could not abide the idea of human beings actually eating each other for food. This is a resonant historical irony, given that they have long been saddled with the reputation of being rapacious man-eaters themselves.

The Karankawas watched the Spaniards die, and then they began to die themselves. During the course of that terrible winter, over half the Indians on the island perished. So many died so suddenly that the Indians’ mourning customs—elaborate burials and cremations, the drinking of water mixed with the pulverized bones of the deceased, a year of ritual weeping at every sunrise—became impossible to carry out. Undone with grief and bewilderment, they assumed the Spaniards were murdering them through some sort of dark magic. And there was indeed an invisible lethal force at work, one that had already ravaged the indigenous people of the Indies and in years to come would bring unimaginable catastrophe to native populations throughout the Americas: Old World pathogens like smallpox and measles, for which the Karankawas had no immunity.

The traumatized Indians who survived this initial epidemic spared the Spaniards’ lives, but grudgingly. Having first taken their visitors in out of charity, they now made them slaves. Cabeza de Vaca and the others were continually beaten and threatened, and forced to dig up roots from the freezing saltwater marshes with their bleeding fingers. In the spring of 1529, thirteen of the Spaniards managed to escape from Malhado and make their way south along the coast, determined to somehow still reach the Spanish settlement at Pánuco. Cabeza de Vaca was too ill to join the trek, but when he recovered, he too fled the island for the mainland, where he fell in with a tribe called the Charrucos, who treated him better and put him to work as a long-distance peddler. They sent him off on long solitary trading missions deep into the heart of the country, where he bartered for hides and flint, offering seashells and pearls from the coast in exchange. Traveling alone in an alien land, in constant peril from hunger and thirst and hostile weather, he was nevertheless exhilarated by his liberation from his enslavement on Malhado, and by a newfound sense of purpose and confidence.

This occupation served me very well, because practicing it, I had the freedom to go where I wanted, and I was not constrained in any way nor enslaved.

The words are from a book Cabeza de Vaca wrote that has come to be known as La Relación, or The Account. Acknowledging in a preface that its contents would be “very difficult for some to believe,” he published the book in Spain in 1542, with a second edition thirteen years later. It’s one of the world’s rare books, but there are places, like the Wittliff Collections at Texas State University, in San Marcos, where you can ask for it and hold it in your own hands. The double-headed eagle of Charles V is on the frontispiece, the ancient rag paper is pleasingly supple, the pages so dense with sixteenth-century typography there are hardly any margins. La Relación is the first book ever written about Texas. It’s a work of survival literature, of natural history, of anthropology, of what must have seemed to readers of the time to be extraterrestrial travel.

The book recounts the doomed voyage from Cuba to Florida and the desperate attempt to sail on to the Río de las Palmas on rafts, as well as the almost six years Cabeza de Vaca spent wandering with his trade goods through the interior of Texas and up and down its desolate coast. He wrote about the strange and frightening customs he witnessed among the people he encountered—their theatrical weeping and fluid gender roles, the way that unwanted female babies were sometimes buried alive or fed to dogs, the contrasting tenderness toward children and unstoppable grief when they died. He wrote about “vipers that kill men when they strike” and about vast herds of “cows” that ranged down from the north, creatures with long fur and curved horns like Moorish cattle—the first-ever written reference to buffalo.

For most of those years he was separated from his fellow Spaniards. But in 1533, in the pecan forests near the mouth of San Antonio Bay where all the bands of the region migrated in the spring to gather nuts, Cabeza de Vaca encountered what was left of the group that had set out years earlier for Pánuco when he was too sick to join them. Of those thirteen men, only three were still alive, and their long odyssey to the Spanish settlement had been interrupted by years of captivity and servitude among the various tribes that inhabited the coastal prairies of South Texas. Two of the men, Andrés Dorantes de Carranza and Alonso del Castillo Maldonado, were, like Cabeza de Vaca, soldiers of noble rank. The third is referred to in La Relación by the diminutive version of the Christian name—Esteban—that had been assigned to him after he was captured by slavers, probably somewhere in sub-Saharan Africa, and sold in the markets of Morocco or Spain. He had come to the New World as the property of Dorantes. Now, along with his master, Estebanico was a new sort of slave, in bondage not just to the inscrutable mores of the alien peoples he had encountered but to the imprisoning wilderness all around him.

It had been six years since their rafts came ashore on Malhado, but the four men still dreamed of reaching the Spanish settlement at Pánuco. It would be two more frustrating years before they could coordinate their escape. They finally slipped away in the spring of 1535, during the time of year when the native groups scattered throughout the region moved south toward the Nueces River for the annual harvest of the prickly pear fruits, which grew there in staggering abundance.

The four escapees trekked through an inhospitable landscape of cactus, thorny brush, and shadeless, spindly trees. Though the Spanish outpost of Pánuco lay on the coast three hundred miles south, they kept well inland, where they had learned from experience that the people tended to be more welcoming to strangers. They came to the Rio Grande, shallow enough to wade across but, as Cabeza de Vaca wrote, wider than the Guadalquivir down which Narváez’s impressive fleet had first sailed.

The country was harsh, but the four castaways were no longer wretched. They had learned the languages and the customs of the people among whom they had passed, and they were conditioned to hardship and unsurprised by it. Also, they were beginning to emerge from servitude into celebrity.

Back on Malhado, the castaways had been pressed into service as healers. Cabeza de Vaca and the others were nervous practicing an art about which they knew nothing, whose stakes were high and whose results they could not control. But the Karankawas threatened to let them starve if they didn’t comply. So the Spaniards cautiously began, adding their own Christian flourishes—the sign of the cross, the Lord’s Prayer—to the native repertoire of ritual healing. The two forms of magic turned out to be compatible enough for at least some healing to take place, and the castaways, even though they were still slaves, began to take on the power of shamans.

By the time they crossed the Rio Grande, they had developed a surging reputation. Each tribe they encountered had heard of their cures, and as they ventured deeper into Mexico, they accumulated a constant entourage of people eager to see the foreigners and witness their miracles. Often Estebanico went ahead as a kind of mysterious herald, the inhabitants startled and mesmerized by his black skin.

They were only about two hundred miles from Pánuco, the Spanish province that had been the focus of all their dreams of salvation, when they turned west, moving far away from the coast and toward the peaks of the Sierra Madre. No longer starving, no longer enslaved, they now enjoyed a superhuman status among the people they met, who followed them from one village to the next in processions that grew to number in the thousands. If in the previous years they had felt forsaken by God, perhaps now they sensed his guiding hand as they blew their healing breath over the bodies of the afflicted or even performed surgery on them with flint knives and sutured the incisions with deer-bone needles. It seems plausible that they turned away from the coast and moved deeper into the interior out of a reawakened sense of discovery. Along the way they encountered things that encouraged them: an intricately worked copper bell with a human face, cotton blankets, baskets of maize. All of this indicated that, if they kept going, they might still fulfill one of the original purposes of the Narváez expedition: to discover cities of vast wealth like the one Cortés had found in the Valley of Mexico.

They found further hints of what might lie ahead when they turned north again and recrossed the Rio Grande back into what is now Texas, many miles upstream from where they had first crossed it. Beyond, where the Rio Grande met the Conchos in the Junta de los Ríos, near where the town of Presidio is today, they entered the fertile country of the Jumanos, an agricultural people who lived in flat-roofed stone apartments—“the first dwellings we saw that had the semblance and appearance of houses.”

They lingered with the Jumanos and then kept on, believing that “going the route of the setting sun we would find what we desired.” They were constantly followed by a crowd of native disciples. “They always accompanied us,” Cabeza de Vaca wrote, “until they left us handed over to others. And among all these peoples, it was taken for certain that we came from the sky.” And it was in the sky, the Spaniards preached to the Indians, that their God lived. If they believed in him too, if they obeyed his teachings, things “would go very well for them.”

But things did not go well for the people who accompanied Cabeza de Vaca. After following the Rio Grande north for several weeks, the party turned southwest, still moving in the direction of the setting sun, searching for the cities of great wealth and sophistication they had come to believe lay beyond the horizon. They made their way through the Chihuahuan Desert, through the mountain passes of the western Sierra Madre, down to the coastal plateaus of the Gulf of California. In a little more than six months, they had walked across the continent of North America. And now they were among people who were not naked hunter-gatherers but who lived in stable houses and grew crops and wore shirts and robes of finely woven cotton. By this time, the desperate men from Malhado had reached their highest level of spiritual influence. In one village, they were given a gift of six hundred deer hearts. Mothers who had just given birth presented their infants to the healers so that they could be blessed with the sign of the cross.

They met an Indian wearing a necklace fashioned from the buckle of a Spanish sword belt. This could only mean that the countrymen they had been seeking in the wilderness for eight years were at last somewhere nearby. Cabeza de Vaca and the others pressed anxiously on, reassuring their Indian followers, telling them they would intercede with any Christians so that “they should not kill them or take them as slaves.”

But they moved through a country now that had been devastated—villages burned and almost deserted, the few remaining people sick and starving, the rest fled to the mountains or taken captive. Finally, at the end of Cabeza de Vaca’s unimaginably long road, he encountered the cause of this havoc. One day he found himself staring up at four Spaniards mounted on horseback, “who experienced great shock upon seeing me so strangely dressed and in the company of Indians. They remained looking at me a long time, so astonished that they neither spoke nor managed to ask me anything.” The bearded, helmeted men looking down in stupefaction from their horses were part of a slave-hunting expedition in the service of Nuño de Guzmán, the governor of the Mexican province of Nueva Galicia.

It was 1536, a time when a fervent argument was raging over the “capacity” of the people the Spanish had discovered inhabiting the New World. Were they some low, half-bestial variant of humanity, or had God given them souls that might be brought to salvation, and slumbering intellects that could be awakened and made to understand the gospels and the mysteries of faith? Passionate, conscience-torn priests like Antonio de Montesinos, who in 1511 shocked the conquistadors of Hispaniola by asking, “Are these Indians not men? Do they not have rational souls?” and Bartolomé de las Casas, who as a young man had witnessed Narváez’s rampages in Cuba, had begun to win the argument, at least in the courts of philosophy. And a year later, in 1537, Pope Paul III would issue the bull Sublimis Deus, which decreed that “Indians and all other people who may later be discovered by Christians, are by no means to be deprived of their liberty or the possession of their property . . . nor should they be in any way enslaved.”

But such distant moral declarations were only limp pieties on the ground in New Spain, where men like Guzmán needed slaves to work their extensive lands and their silver and gold mines, and to export to the Antilles in exchange for livestock and other commodities. Cabeza de Vaca pleaded for the freedom of the Indians who were traveling with his party, but the Spanish captain, interested only in enslaving them, sent the castaways off under armed guard to the town of Culiacán, where they could not interfere. A few months later they arrived in Mexico City, where they astonished Viceroy Don Antonio de Mendoza and Hernán Cortés himself with their story of having survived the doomed Narváez expedition and managing to stay alive for eight long years in a vast wilderness no other European had ever seen. The wanderers had trouble readjusting to Spanish life, feeling weighed down by their borrowed clothes and unable to sleep comfortably anywhere except on the ground. And Cabeza de Vaca’s conscience—expanded by the experience of being saved, enslaved, and finally venerated by an ever-changing cast of native peoples—was no longer a natural fit with the hubristic spirit of conquest. But that spirit was still ferociously bright among the other adelantados and adventurers who would follow him, anxious to embark on their own quests to find the golden cities they believed had to exist somewhere in Texas or beyond.

Excerpted from They Came From the Sky: The Spanish Arrive in Texas, a Preview of a Forthcoming History of Texas, courtesy of the University of Texas Press.

- More About:

- Books

- Stephen Harrigan

- Galveston