On December 26, 1985, when he was forty years old, Whitley Strieber awoke as he was being carried out of his cabin in New York’s Hudson Valley to a tent in the surrounding woods, where he was beaten, poked, and prodded by unknown assailants. A circle of observers around him included giant insects and masked, trollish figures as well as an old friend—human—whom Strieber later learned had died several months earlier. In the years that followed, Strieber had more strange experiences with entities he came to call the “visitors”: One night, he found himself in flagrante delicto with an otherworldly lover. A year or two later, two mysterious beings implanted a small piece of metal in his ear. Over time he recalled events that had happened much earlier in his life: encounters with diminutive blue men, out-of-body experiences, and strange childhood episodes at Randolph Air Force Base, in his native San Antonio.

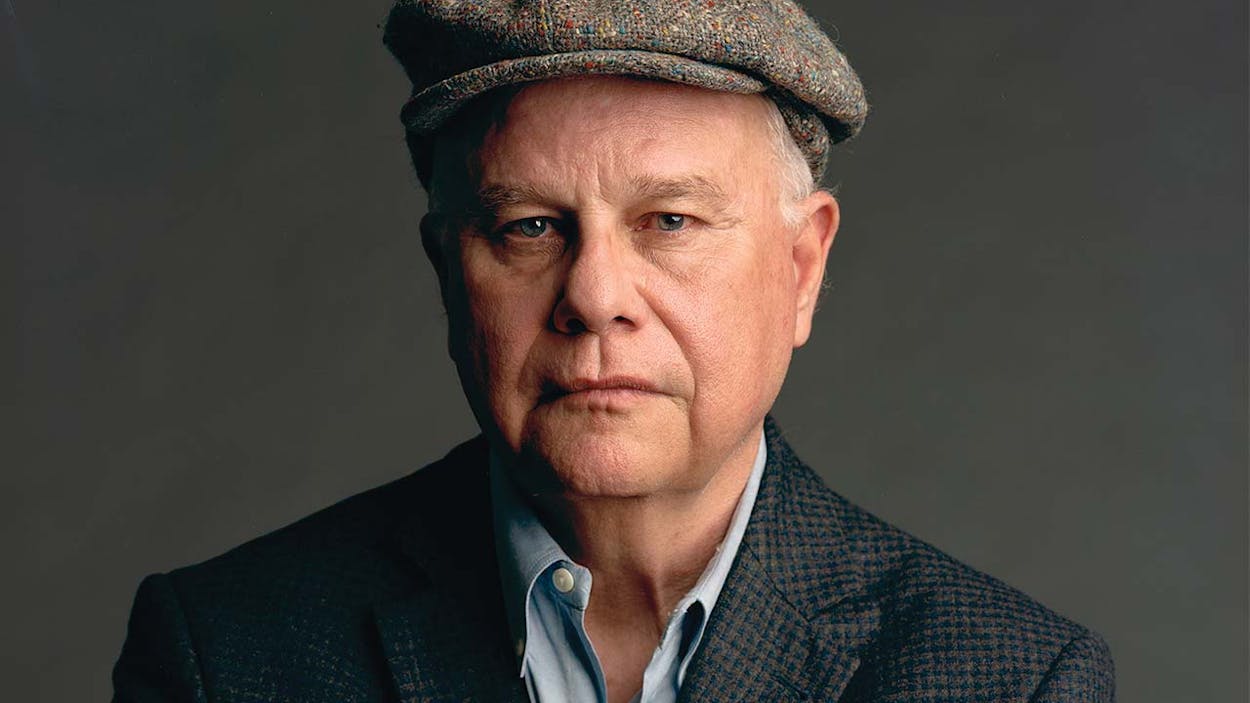

At least, this is what Strieber perceived happened to him, as recorded in his best-selling 1987 book, Communion, and several sequels. As a result, he became “the poster boy for alien abduction,” despite maintaining that he didn’t know exactly what had happened to him; after Communion’s publication Strieber received nearly half a million letters from readers describing their own close encounters. “My first books were unfortunate in one respect, in that they were so vividly written that readers and the media looked at them as descriptions of experience rather than descriptions of perception,” he says. “There’s a great deal of difference between the two.”

Though critics were often savage (the Los Angeles Times refused to place the first sequel to Communion on its nonfiction best-seller list; the book appeared on the fiction list instead), Strieber has stuck to his guns. This month he will release his thirty-sixth book, The Super Natural: A New Vision of the Unexplained, a collaboration with Rice University professor of religion Jeffrey Kripal that considers Strieber’s experiences through the lens of comparative religious study. Its chapters alternate between Strieber’s autobiographical accounts and Kripal’s examination of those reports using the tools of his discipline. Kripal, whose research interests include the mystical and paranormal, suggests that Strieber’s experiences with the “visitors” are not unlike St. Paul’s encounter on the road to Damascus or Moses’ interaction with the burning bush. If Strieber is telling the truth—and Kripal is convinced he is—his accounts might offer religious historians a modern case study of a perceived encounter with extraordinary beings.

Strieber, who splits his time between San Antonio and California, calls Kripal “the only person of any intellectual standing who’s ever understood my work” and sees The Super Natural as a step toward gaining the attention of the intellectual community, not just fans of the paranormal. In fact, though the book was published by a division of Penguin, he hopes that it will reach a smaller, more educated audience. “When a mass audience was interested back in the Communion days, it was a disaster,” he says. “The book was immediately sensationalized, and I was swept up in this circus that I couldn’t control.”

Strieber is emphatic when he says that he doesn’t believe in the supernatural or the paranormal; he simply believes that humans don’t understand all the laws of nature yet. Hence the all-important space in the book’s title. “To me ‘the supernatural’ is something outside of nature, so Jeff and I call it the ‘super natural’—two words—because it is part of nature,” Strieber says. “We need to accept the fact that there are things that happen around us that are not explained by science. But that doesn’t mean that they can’t be.”

This past December 26 marked the thirtieth anniversary of Strieber’s life-changing experience in the woods, but he says it was a date that passed without fanfare; his wife, Anne, died in August, and he was grieving too deeply to reflect on it. Still, as has been the case for the past three decades, he wakes in a panic nearly every night at 3 a.m., the moment he claims he was startled awake in the cabin. But he doesn’t seem to mind living with so many unanswered questions. “I’m actually very lucky in that respect,” he says. “It’s a wonderful place to be if you like being driven slightly mad by your own life.”

- More About:

- Books

- San Antonio