From the tidy bedroom of her small central Austin apartment, University of Texas at Austin student Sakunthala Gopinath takes a long moment to get into character. Playing the role of Celia—the lively, occasionally sarcastic foil to protagonist Rosalind—in Shakespeare’s pastoral comedy As You Like It. The senior economics major, who goes by Saku, imagines herself lost in the play’s lush forest setting, rather than quarantined in a student-filled neighborhood west of campus. Normally the heroine’s fun-loving, sass-forward personality comes instinctively to her; today, though, Gopinath is finding it difficult to embody her character over a screen.

With the online videoconferencing software Zoom now acting as her stage, Gopinath prepares for her big moment—Act IV, Scene iii—where Celia falls head over heels for the play’s reformed antagonist, Oliver. As her scene partner Nolan Burdett, a senior humanities major, eagerly launches into his character’s passionate monologue, Gopinath struggles to maintain direct eye contact with her audience—that is, her webcam.

“Sorry,” she says, stopping the scene. “But I’m supposed to be falling in love with Nolan. How can I do that when I can’t even see his face?”

For Gopinath and her classmates, Shakespeare’s oft-quoted line “All the world’s a stage” has taken on an unexpected new meaning as of late. In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, the University of Texas moved all of its classes to an online format on March 30—including Gopinath and Burdett’s Shakespeare Through Performance course, also known as Shakespeare at Winedale.

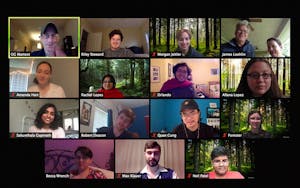

Officially listed as an English course rather than a theater offering, Shakespeare at Winedale requires no prerequisite performance background of its participants; all that’s needed is a strong openness to intensive creative collaboration. Every fall, students from all levels and academic backgrounds apply and interview for the class, with sixteen making the cut. Typically, the group stages a full play at the end of the course—but given the pandemic and the necessity of social distancing to slow its spread, they’ve come up with an inventive and ambitious contingency plan: they’ll be staging As You Like It entirely over Zoom this weekend. “These students have had to pivot online in the middle of the semester, when the play’s been cast and rehearsals have already started,” says Liz Fisher, program coordinator for Shakespeare at Winedale. “Now they’re working to figure out what performance looks like in this new world.”

The course’s instructor, English professor James N. Loehlin, understands his student’s frustration. For twenty years, the Shakespeare scholar has used physical performance to teach the playwright’s work; in this class, 65 percent of a student’s final grade is tied to daily dramatic scene readings and memorized, off-book presentations. It’s a uniquely hands-on pedagogy, one that Loehlin believes results in richer class discussions and deeper textual understandings than a traditional lecture model. “[Moving the class to Zoom] is not remotely something I would ever have chosen to do,” he says. “Even if everyone’s in the right spirit of participating, it’s just harder to create the sense of engagement you find in a classroom.”

When students signed up for Loehlin’s course, they expected not only to stage As You Like It in person, but also to participate in a long-standing university tradition. Since 1970, participants in UT’s Shakespeare at Winedale courses have traveled to the Winedale historical complex in Round Top to rehearse and perform Shakespeare’s work on the Winedale stage—a renovated nineteenth-century barn given to the program by renowned Texas philanthropist Ima Hogg. Spring course participants head up to Winedale for three full weekends, while students in the more intensive summer class stay there for ten weeks.

For many program participants, past or present, the trips to Round Top are the program’s main draw. “At Winedale, we’re in the middle of nowhere,” says senior business major Neil Patel, who considers the program to be the final item on his “college bucket list.” “When we’d rehearse scenes taking place in nature, we’d walk to this clearing where trees surrounded us. Though that’d be our first and last rehearsal in Winedale, that experience—putting ourselves in the same situation as our characters—was invaluable.”

Professor James “Doc” Ayres aimed for students to have these kinds of experiences when he established the Shakespeare at Winedale program in 1970, even as he faced backlash from his department colleagues—many of whom considered performance to have no place in an English class. “The administration was very slow to recognize the value of the program because it wasn’t a traditional [way of teaching]. For several years, it refused to let me offer the course,” says Ayres. “I didn’t wait for permission when I started Shakespeare at Winedale, I just started it in my classroom. When Miss Hogg told me she wanted us to take our performances into the barn, again, I didn’t ask the department’s permission. I’ve been operating like that my whole career.”

Ayres’s can-do spirit would transform this course from the English department’s black sheep into perhaps its most beloved tradition. Nonetheless, COVID-19 has put an unceremonious halt to Shakespeare at Winedale’s 2020 summer class, children’s camps, and numerous other gatherings planned throughout the year in honor of the program’s fiftieth anniversary. So, if convening in Round Top isn’t an option for now, what exactly is Shakespeare at Winedale to do?

“We adapt,” says Fisher. “That’s what the entire program’s been about since the beginning. We make it work, no matter the constraints or challenges.” With the spring course’s final performance already in production, Loehlin, in true Winedale fashion, has remained adamant about staging As You Like It live. “[Loehlin] is carrying on Doc’s spirit, “says doctoral candidate Robert Jones, Loehlin’s teaching assistant and former pupil. “I remember one year at Winedale, we were digging through mud to lay some electrical wires. It was cold, rainy, and we were getting eaten by fire ants, but James was like, ‘Wow this soil is interesting,’ making a point about why the German immigrants might have settled there due to Round Top’s soil. That spirit of ‘Okay, what can we get out of this?’ is a Winedale-ian thing.”

Though a boon to Loehlin’s students’ morale, Winedale-ian spirit doesn’t exactly answer a burning question in our current times: what exactly is online theater? “Well, it’s not quite theater in the traditional sense, but it’s not quite film either,“ says Fisher, whose past theatrical projects (e.g. 2015’s Deus Ex Machina) have explored digital audience interactivity by allowing audience members to dictate the play’s outcome in real time via text messages. “It’s this gray area that’s at the intersection of both.” While Fisher’s digital work has never involved staging Shakespeare virtually, it was her idea to upgrade the class to Zoom’s more versatile webinar format.

Even with enhanced technology, such a drastic change in medium comes with its own challenges. “I have a pretty bad Wi-Fi connection,” says Patel. “So sometimes I think I’m reacting to a line on time, but I might be listening to delayed audio and end up laughing at a really dark moment.” For Loehlin, not having the audience present also dilutes the full experience. “One thing that’s tough to lose is [audience’s] laughter. With [their mics] muted, you’re missing an important part of the experience of a Shakespearean comedy.”

In spite of the frustrating roadblocks, online rehearsals have presented unlikely opportunities for creativity, too. Since moving to Zoom, Loehlin’s class has become a virtual laboratory for theatrical experimentation: During a rehearsal in mid-April, the professor divides his class into several breakout rooms (smaller individual group meetings within a larger zoom video call) and checks in on each sporadically. In one room, two actors—while choreographing a fight scene—explore ways to simulate a headlock. Elsewhere, a group rehearses Act II’s song, “Ducdame,” which senior business major Quan Cung has arranged into a gospel-style, call-and-response hymn. Despite grainy audio and spotty Wi-Fi, the tune carries through the virtual rehearsal, inspiring the cast to sway along. All together it’s a hectic and lively process, but it’s unmistakably theater. “The biggest thrill is that this medium doesn’t have rules yet,” says Jones. “We’re creating our own conventions.”

“Winedale has been the one class that Zoom’s made more interesting,” says Patel. “We’re adapting the play to a totally different circumstance. This isn’t half-assed Shakespeare on Zoom; this is Zoom Shakespeare.” One such medium-oriented adaptation, for instance, features actors lighting candles to simulate a divine aura surrounding the character Hymen’s video feed. Elsewhere in the play, a scene that originally saw a lovesick character profess his love to another by nailing poorly written poetry to trees now has the suitor typing out his embarrassing professions in the Zoom group chat for everyone—including the audience—to read.

While these creative experimentations are no doubt impressive, it’s still ironic that Loehlin originally chose As You Like It to celebrate the act of gathering at Round Top. “The semester was designed to celebrate what we’re calling Shakespeare’s Green World,” says Loehlin. A literary concept first designed by critic Northrop Frye, the Green World encapsulates plots such as the one in As You Like It, wherein characters escape from cities to a natural setting to discover things like truth and beauty. “This topic seemed so appropriate going into our fiftieth anniversary because Winedale is our green space,” says Fisher. “We escape to Winedale to learn more about ourselves and become whole.”

Given the circumstances, Loehlin has worked to improvise a Green World experience for his students. “During one rehearsal, when the play transitioned from a court to forest setting, we took our laptops outside,” he says. “While I was imagining a Wizard of Oz monochrome-turns-to-color effect, there happened to be a thunderstorm that day. Many students’ outside worlds were rainy and cold, which was surprisingly effective for Duke Senior’s speech about the conditions in exile—about how winter’s wind biting is still better than the corrupt world he and his men left behind. In that moment, we felt the harshness that the characters experience, but also a sense of our own exile.”

Re-creating the harshness of exile might not have been Loehlin’s initial plan for students, but such on-the-fly adaptation nonetheless presents a powerful opportunity to study Shakespeare from an underexplored perspective. As a result, staging As You Like It digitally has perhaps become less a reflection of the student’s rehearsal process and more of a model of things to come. “I’ve taken to [reading the play] as ‘this is what we have to look forward to when the pandemic is over,’” says Gopinath. “We’ll be able to go back out into the Green World with a better appreciation of it.”

As the play’s opening night approaches, the students have rehearsed constantly to present Shakespeare at Winedale’s first virtual production. To witness the fruits of the class’s creative labor, audience members can watch the free livestream performance of As You Like It Saturday, May 2, at 5 p.m. Central on the official Shakespeare at Winedale Facebook page. (For those unable to attend Saturday’s livestream, a recording of the event will be made available on the page immediately after.)

In Loehlin’s view, his class already has overcome the semester’s greatest challenge and has found novel ways to experience history’s most lauded playwright through it. “Shakespeare at Winedale has never been about the final performance, it’s been about the learning process,” he says. “That’s what keeps us returning to Shakespeare. We come back to his plays at different moments and under different conditions in life, and every time we’re able to find meaningful takeaways within them.”

- More About:

- Theater