On June 4, after one of their first in-person practices since the coronavirus outbreak, the Texas Longhorns football team lined up outside Darrell K Royal—Texas Memorial Stadium and began to march toward downtown Austin. They were joining thousands of others across the world protesting the killing of George Floyd; when they reached the Texas Capitol, players, coaches, and support staff knelt in silence for eight minutes and 46 seconds, the length of time Floyd was pinned to the ground with a policeman’s knee on his neck. Then head coach Tom Herman addressed his players: “You’re a minority football player at one of the biggest brands in the country. You have a voice. Use it.”

His players took that message to heart. Days later, a group of more than two dozen Texas student athletes—including football, basketball, and track stars—posted a letter on social media in which they vowed not to participate in upcoming recruiting or fund-raising events until the university administration addressed a series of concerns. Those included renaming certain buildings on campus that are named for men who supported the Confederacy or segregation, creating an outreach program for underprivileged communities, and establishing a permanent exhibit centered on the history of black athletes in the Texas Athletics Hall of Fame, which opened last year and features statues of running backs Earl Campbell and Ricky Williams. “As ambassadors, it is our duty to utilize our voice and role as leaders in the community to push for change to the benefit of the entire UT community,” they wrote. In particular, the final item on the players’ agenda has ignited a debate throughout the Longhorn community over the past week: they called for officials to replace “‘The Eyes of Texas’ with a new song without racial undertones.”

“The Eyes of Texas” is not your typical school song. It’s something closer to a prayer. (“The Eyes of Texas” is UT’s official alma mater tune and an unofficial fight song; the school’s official fight song is “Texas Fight”). Texas Longhorns sing it to begin and end every UT game. Alumni join in song at weddings and funerals, and they whisper it to their babies as they rock them to sleep. At the 1960 Democratic National Convention, a twenty-piece band played the tune to introduce Lyndon B. Johnson onstage. According to multiple football players who played under coach Mack Brown, incoming freshmen were instructed to meet with Jeff “Mad Dog” Madden, the strength and conditioning coach, to learn the words to the song before even coming onto the field for their first practice.

For many Longhorns—myself included—the athletes’ letter marked the first time they had learned of the song’s problematic origins. “The Eyes of Texas” had always been a part of my life as a fifth-generation Longhorn, with words as ubiquitous as those in “Twinkle, Twinkle Little Star.” I had never questioned where those songs came from; I assumed they had always been there.

A reckoning with the past of “The Eyes of Texas” has been gaining momentum in recent years, though. About a decade ago, a group of Texas basketball players refused to sing it after learning the song’s history, and just two years ago, the Texas student government debated the merits of the song. Neither movement got much attention at the time—but now that monuments to the United States’ racist history are toppling around the country, this call to action has been reinvigorated.

To trace the history of the tune, you must go back to the turn of the twentieth century, when William Prather was president of the university. In a 1938 memoir, T.U. Taylor, the first dean of the College of Engineering at Texas, alleged that the phrase, “the eyes of Texas are upon you,” was a reference to something Robert E. Lee often told students when he was the president of Washington College, in Virginia, where Prather studied law in the late 1860s. Taylor claimed that Lee often told students, “The eyes of the South are upon you,” as a way of reminding them to work hard and uphold Southern traditions. For more than 80 years, that story was accepted as fact. But a recent report to study the song’s origins could not find any primary sources that show that Lee ever used the phrase.

Instead the report found that Prather, who became UT’s president in 1899, more likely found his inspiration from Confederate brigadier general John Gregg of Texas. Gregg reportedly once told his soldiers, “The eyes of General Lee are upon you!” But, the report notes, similar phrases had been used long before the Civil War, including in the Book of Job (“For His eyes are on the ways of a man.”) and by George Washington (“The eyes of all our countrymen are now upon us”).

But it was Gregg’s saying that Prather referenced when speaking to students after being named president. According to a 1926 Dallas Morning News column remembering her father, Prather’s daughter said her father gave a speech where he recounted Gregg leading troops into battle. She said that the crowd roared when the president said: “I would like to paraphrase [Gregg’s] utterance, and say to you, ‘Forward, young men and women of the University, the eyes of Texas are upon you!”

From then on, it became Prather’s catchphrase. His daughter recalled one instance when students were waiting to hear the president speak. “Bet you a quarter he says ‘eyes of Texas’ before he gets through,” one student said to another. He won the quarter.

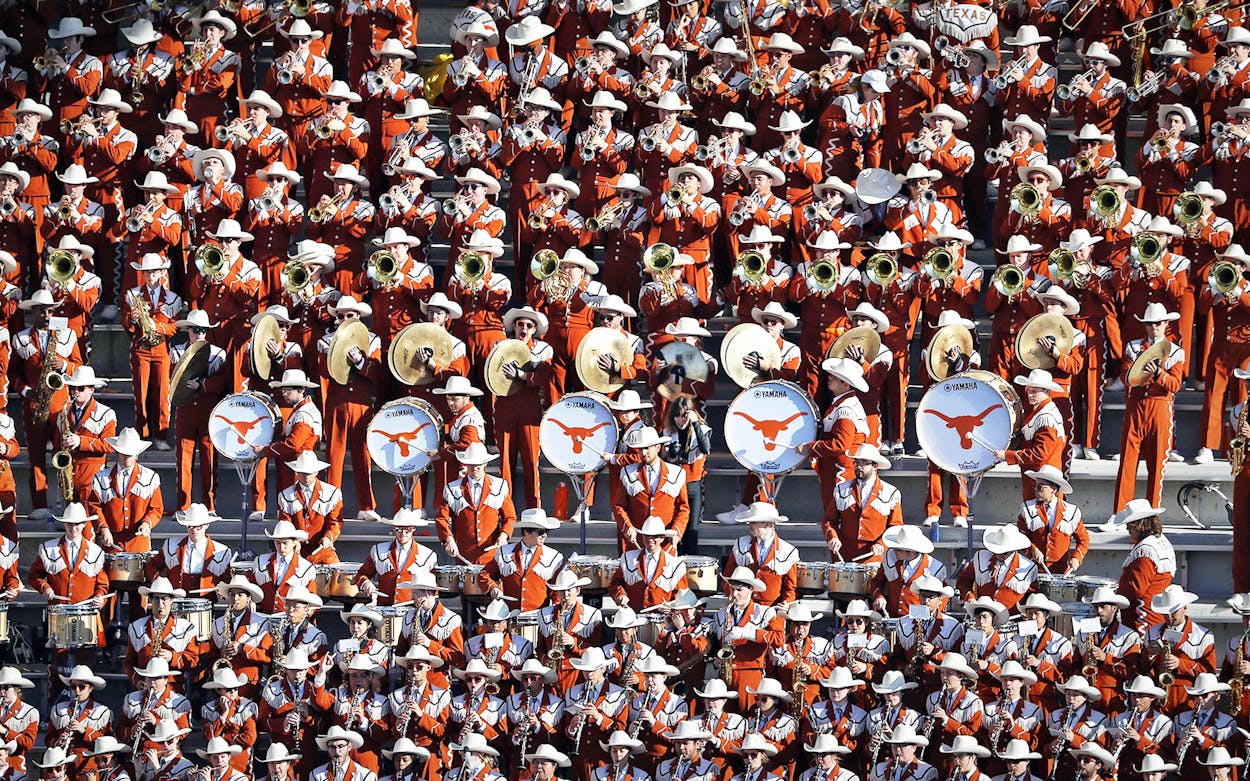

In 1902, a UT student named Lewis Johnson made it his personal mission to create a school song. He played tuba in the band, directed the school choir, and began something called Promenade Concerts, where the marching band would move through campus playing overtures and marches by John Philip Sousa. It bothered him that they played other schools’ songs, like “Fair Harvard.” He wanted a tune to call Texas’s own, but didn’t know how to write the lyrics.

He approached his classmate John L. Sinclair, the editor of the yearbook. Together, Johnson and Sinclair wrote a song titled “Jolly Students of Varsity,” but it wasn’t quite what they wanted, so they shelved the idea. Nearly a year later, Johnson was standing in line at the post office when Sinclair ran up to him and handed him a scrap of paper torn from a bundle of groceries. He’d had a flash of inspiration, he said. Scribbled on the paper, he had written a poem:

They watch above you all the day, the bright blue eyes of Texas. At midnight they’re with you all the way, the sleepless eyes of Texas. The eyes of Texas are upon you, all the livelong day. The eyes of Texas are upon you. They’re with you all the way. They watch you through the peaceful night. They watch you in the early dawn, when from the eastern skies the high light, tells that the night is gone. Sing me a song of Texas, and Texas’ myriad eyes. Countless as the bright stars, that fill the midnight skies. Vandyke brown, vermillion, sepia, Prussian blue, Ivory black and crimson lac, and eyes of every hue.

The two students decided to tweak the lyrics to more explicitly pay homage to Prather’s catchphrase. Johnson suggested that they set the lyrics to the tune of “I’ve Been Working on the Railroad,” and they eyed an annual campus minstrel show on May 12, 1903, as the right time to debut it, since there would be a large audience, including President Prather. These minstrel shows, which went on until the sixties, were fund-raisers organized by students and featured white performers singing and dancing in blackface.

The “Varsity quartet,” with Johnson on tuba and Sinclair on banjo, performed after the school choir, in the middle of the show. According to Gordon, it’s likely that the men donned blackface onstage as they performed the song. Their performance was a hit, and the crowd demanded that they play the song again and again. The very next day, on one of Johnson’s Promenade Concerts, the band marched through campus playing the song while students sang along. That fall, during UT’s annual bout with Texas A&M, the Aggies were driving late in the fourth quarter when they took a timeout. A student started singing the words, and soon, hundreds of others at Clark Field were joining in. A tradition was born, and “The Eyes of Texas” eventually became ingrained into Longhorn student life.

The backlash surrounding ‘Eyes’ has grown considerably in the five days since the student athletes’ letter was published. Student government and the university’s Black Student Alliance voiced their support of the statement. And on Tuesday morning, a group of former Longhorn athletes, including Cat Osterman and Quan Cosby, tweeted a statement in solidarity with current athletes. “They’re not asking for new iPads, and we already have the best locker rooms in the country,” says Daron K. Roberts, the founder of UT’s Center for Sports Leadership and Innovation. “They’re asking for institutional changes that they think can have an impact on the racism that they see.”

Other people—including alumni—are resistant to the change, citing tradition. On message boards and comment sections, detractors say that the song’s meaning has changed over the years. John Burt, a receiver who graduated in 2019, told the school paper, “Whenever I sang ‘The Eyes of Texas,’ I was singing it because it’s the school song, and I was singing it purely out of school pride.”

In spite of the song’s origins, the Texas athletics department has yet to take a stance either way—and it’s unclear if it will be sung again come fall. Athletics director Chris Del Conte tweeted in response to the letter: “I am always willing to have meaningful conversations regarding any concerns our student athletes have. We will do the same in this situation and look forward to having those discussions.” (The athletics department declined to comment for this story.) In an email to students earlier this week, interim president Jay Hartzell wrote: “Working together, we will create a plan this summer to address these issues, do better for our students and help overcome racism,” although he never addressed the song by name.

If UT has proved anything over the years, it’s that change happens slowly and traditions have a stubborn grasp on the institution. Since around 2001, Gordon has been leading “racial geography” tours of the UT campus that highlight the school’s forgotten racist history. One subject of Gordon’s tour is George Washington Littlefield. Littlefield has long been known as one of UT’s earliest and most prolific donors, and all around campus, you can still see his influence: a cafe and residence hall are named after him, and two of the campus’s most prominent landmarks are the Littlefield Home and Littlefield Fountain.

In their letter, student athletes are calling for his name to be removed from Littlefield Hall because, as Gordon teaches, Littlefield was a slave owner who fought for the Confederacy in the Civil War. Late in his life, Littlefield poured money into making UT more Southern-centric and commissioned Italian sculptor Pompeo Coppini to design statues of Jefferson Davis and Robert E. Lee, as well as his namesake fountain. The fountain’s inscription, which was removed in 2016, described how Confederates were “not dismayed by defeat nor discouraged by misrule [and] builded [sic] from the ruins of a devastating war a greater South.” Interestingly, when he was completing the project, Coppini recommended to Littlefield that the monuments should honor Americans fighting in World War I. When Littlefield refused, Coppini replied: “As time goes by, they will look to the Civil War as a blot on the pages of American history, and the Littlefield Memorial will be resented as keeping up the hatred between the Northern and Southern states.”

In recent weeks, Gordon’s tours of what he calls a “neo-Confederate university” have become so popular that the College of Liberal Arts made them available virtually. For his part, Gordon doesn’t currently have a position on whether or not the university should cease singing “The Eyes of Texas.” Either way, he says, the discussion is vital. “I just think people need to know what its roots are,” he says, “And then we should decide collectively what we want to do about that.”

Update 06/17: This article has been amended to reflect that “The Eyes of Texas” is UT’s alma mater and an unofficial fight song.

- More About:

- Texas History

- Sports