This story originally appeared in the November 2017 issue with the headline “Versions of Lyndon.”

Lyndon Baines Johnson was a floodlit blur in the far distance at the 1964 National Boy Scout Jamboree in Valley Forge, Pennsylvania. Believing that braces, suppurating acne, and incipient baldness were insults enough to the vanity of a fifteen-year-old boy, I wasn’t wearing my glasses and couldn’t pull the president into focus. Nevertheless, there he was, briefly lecturing 50,000 scouts about American values before waving goodbye and thrumming off into the night sky in the presidential helicopter.

It was my second encounter with LBJ. A few years before, when he was vice president and I was briefly trying out an identity as a political fanboy, I met him, sort of, in Corpus Christi. He was in town for something or other, walking past a line of people in the convention center on his way to a press conference. When he was in range, I stepped forward and asked him for his autograph. First impressions: towering, Dumbo-eared, annoyed. The famous Johnson gregariousness was not on display. No bear hugs or headlocks for me. He stopped, he sighed, he said—as if I were to blame for some general unpleasantness—“I hadn’t planned on signing any autographs today.” But what happened next overrode any disappointment I might have felt, for I became a witness to history. It was a moment that would awaken in the soul of a young Texas boy a lifelong fascination with office supplies. Johnson wearily reached into his pocket, withdrew a silver pen, uncapped it, and wrote the interlocking letters “LBJ” on the paper he had taken from my hand. I remember being dazzled by how sumptuous and thick the ink was, and by how light a touch was required for the vice president’s signature to glide into existence. It was the early sixties. I had never heard of such a marvelous thing as a felt-tip pen, and my immediate impression was that Johnson had ordered this revolutionary implement to be created exclusively for his use.

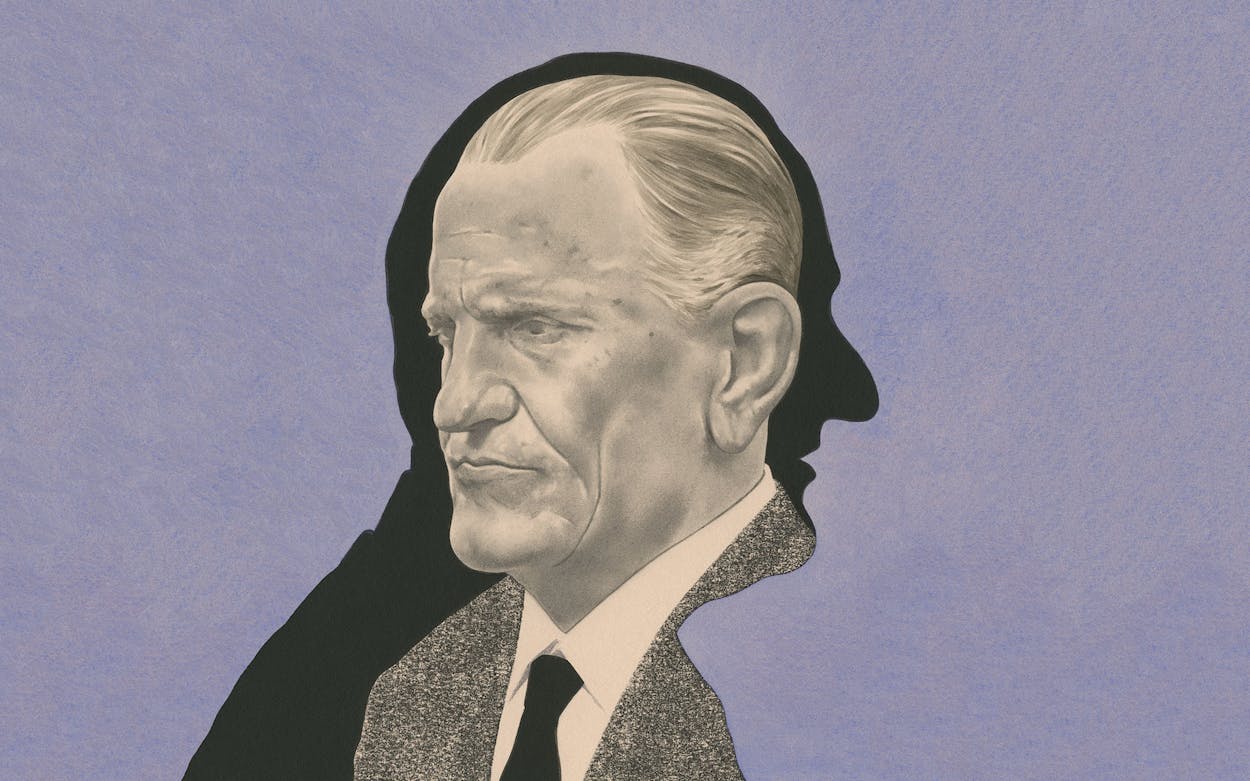

I present these two brush-bys as my personal credentials for judging the fidelity of Woody Harrelson’s performance in a new movie—or make that yet another movie—about LBJ. It’s interesting that Hollywood has not yet exhausted its fixation on Texas’s homely homeboy president, a man who during his triumphant but tragic administration was cringingly devoid of dazzle and mystique. But the exercise of power has a dramatic imperative that trumps glamour, and maybe, in our present age, we’re so starved for simple competence that the sight of a chief executive seducing and conniving and threatening through a rotary telephone receiver appears especially sexy. Whatever is driving the trend, in the past four years Johnson has been reanimated at least four times on-screen, most notably by Bryan Cranston in the HBO adaptation of Robert Schenkkan’s play All the Way, but also in supporting roles by Tom Wilkinson in Selma, John Carroll Lynch in Jackie, and Liev Schreiber in Lee Daniels’ The Butler.

Why the need for another Johnson? I don’t know, since in some ways LBJ, which was written by Joey Hartstone and directed by Rob Reiner, seems to be almost the same movie as All the Way. Although it’s a big-screen feature, it has the soul of a topical TV movie, with a flashback-y narrative structure that is hustled along by the familiar expedient of black-and-white news footage. And like All the Way, it primarily concerns itself with Johnson’s early tenure in office and his transition from cynical political pragmatist to champion of civil rights. The two films have different time signatures—Johnson’s 1963 address to Congress five days after the Kennedy assassination is the effective end point of LBJ, whereas for All the Way, it’s one of the first scenes.

But both screenplays draw from the same deck of tropes: Johnson, with the bathroom door pointedly open, speaking to aides from the oval office of his toilet seat; Johnson relating the story of his African American cook having to squat on the side of the road to urinate on cross-country trips because she wasn’t allowed into whites-only restrooms; Johnson barking at his tailor to leave more room in the crotch of his slacks to allow for his “nutsack” and his “bunghole.” But it’s not all synchronicity. The Kennedy brothers, for instance, never make an appearance in All the Way, whereas in LBJ they’re lively, full-fledged characters.

But back to my expert opinion on Woody Harrelson, which is—pretty good at first and then subtly, inexorably better. When it comes to LBJ portrayals, he certainly belongs in the Big Three with Cranston and Randy Quaid, and there have been periods of quiet contemplation in which I thought he might even be the best. Give yourself a few minutes to get over his alarming makeup job before you pass your own judgment. The first time you see the actor on the screen, as he arrives in Dallas on the morning of the assassination, you might think he looks more like Woody Harrelson with the mumps than like the movie’s title character. The prosthetic jowls, with their deep parenthesis creases on either side of the mouth, are artfully applied, as are the huge, pendulous ears and the extended nose. But it’s such a big face, with Harrelson’s own face sort of peeping bravely out of the middle of it, that it takes a few scenes for a viewer to begin to adjust to it.

Harrelson, though, is at ease and alert beneath this load of latex. Cranston might be better at conveying LBJ’s Mr. Magoo squinty-face, and more precise in replicating the painful sincerity of the president’s public speaking, but the Midland-born Harrelson is a natural degree or two closer to the person he’s playing. Though Johnson was a cosmically impatient man, he was also bred to the unhurried rhythms of his Texas boyhood, and there are moments in LBJ—when the title character isn’t shouting at or belittling somebody or grabbing food off his dinner partner’s plate—that Harrelson speaks and moves with a slow Pedernales trickle that is hypnotically authentic.

In comparison, Cranston can sometimes feel a little rushed, a little too eager for the opportunity to impersonate Lyndon Johnson. This may have something to do with the fact that All the Way began life as a play, and on occasion still seems—with its voice-over soliloquies and center-stage declamations—to be pitched toward a vestigial live audience.

But Cranston and Harrelson are far from the only contestants in the LBJ impersonation derby. It’s an indication of the reliable dramatic utility of the thirty-sixth president that All the Way isn’t even the first movie that HBO has produced about him. In 2002, John Frankenheimer, the director of sixties-era political classics like The Manchurian Candidate and Seven Days in May, made Path to War. Written by Daniel Giat, the movie was a meticulous dramatic study of Johnson’s descent into the tar pit of the Vietnam War. It starred, as the world’s most famous son of the Texas Hill Country, the Irish-born Sir Michael Gambon. Gambon works well enough in the role if you meet him halfway, if you don’t get all worked up whenever he invests too hard in his Texas accent and says “sitchyation” instead of “situation” or makes a reference to the “Soopreme Court.”

Felicity Huffman’s Lady Bird is even broader—“It was a wuhndaful speech . . . and you delivered it so vahrrry well.” But let’s chalk that up to the futility of playing Mrs. Lyndon Johnson in the first place, a role that offers little to do in any of these movies except to smile thinly and abide patiently and buck up her overtaxed husband. Until we have a movie in which Lady Bird is the main attraction, excellent actresses like Jennifer Jason Leigh (in LBJ) and Melissa Leo (in All the Way) are going to be consigned to the same tiresome woman’s-auxiliary role.

Patti Lupone had more to work with than anybody else—or at least more screen time—as Lady Bird in the 1987 made-for-TV movie LBJ: The Early Years. Beginning in 1934, when Johnson was a congressional aide, and ending when he takes the oath of office on Air Force One, the movie is as much a Lyndon ’n Lady Bird love story as it is a rise-to-power narrative. It’s a little hard to track down, and actually watching it will probably mean booting up the VCR that’s been waiting patiently for decades in the bottom of your closet to be of service again, but if you’re an LBJ movie completist, it’s a must-see.

The last few times I checked in on Randy Quaid’s out-of-kilter celebrity odyssey, he was giving a press conference warning about “a malignant tumor of star whackers in Hollywood” and looking for a place to crash during Donald Trump’s inauguration after his RV broke down. But no matter how far he wanders off the grid, I’ll be there to salute him for his performance as the young Lyndon Johnson. Sure, LBJ: The Early Years is a creaky biopic, complete with twirling newspaper headlines and golden California ridges passed off as the Texas Hill Country. Directed by Peter Werner, and co-written by a journeyman screenwriter named Ken Trevey—whose credits reach back all the way to the Mesozoic days of Wagon Train and Naked City—it’s often preposterous (especially so in a scene where young Congressman Johnson’s eyes bulge out of his head at the sight of his soon-to-be paramour Alice Glass leaning across a pool table), but Quaid’s performance of a man whose credo is “I scratch when I itch” is unfailingly insistent. He looks enough like Lyndon Johnson that the only visible makeup required is the Brillo-ish silver in his hair as he ages. Quaid deftly manages his character’s gravitas shift from goofy comer to ruthless power player, a man of such raw needs and such ravenous appetites that he sits behind his desk smoking, drinking, eating a cheeseburger, and slugging back antacid all at the same time.

LBJ: The Early Years appeared fourteen years after Lyndon Johnson died, and about a quarter century after that day in Corpus Christi when I stood next to him as he wielded his magic pen. At that time, I think the only president I had ever seen portrayed in a movie was Charlton Heston’s Andrew Jackson in the 1958 Jean Lafitte epic The Buccaneer. It’s safe to say that Woody Harrelson’s LBJ won’t be the last, and it’s strange to reflect that the person that I met that day has by now been depicted in movies and television—according to a quick recon of the Internet Movie Database—at least fifty times. That may say something about my own advancing age, or about the entertainment industry’s blind impulse to use up history even as it’s happening. But I think it says more about Lyndon Johnson himself, the graceless, grasping, conscience-torn mortal who long ago relinquished his role as our president but shows no sign of surrendering his rule over our national imagination.

- More About:

- Film & TV

- Woody Harrelson

- LBJ