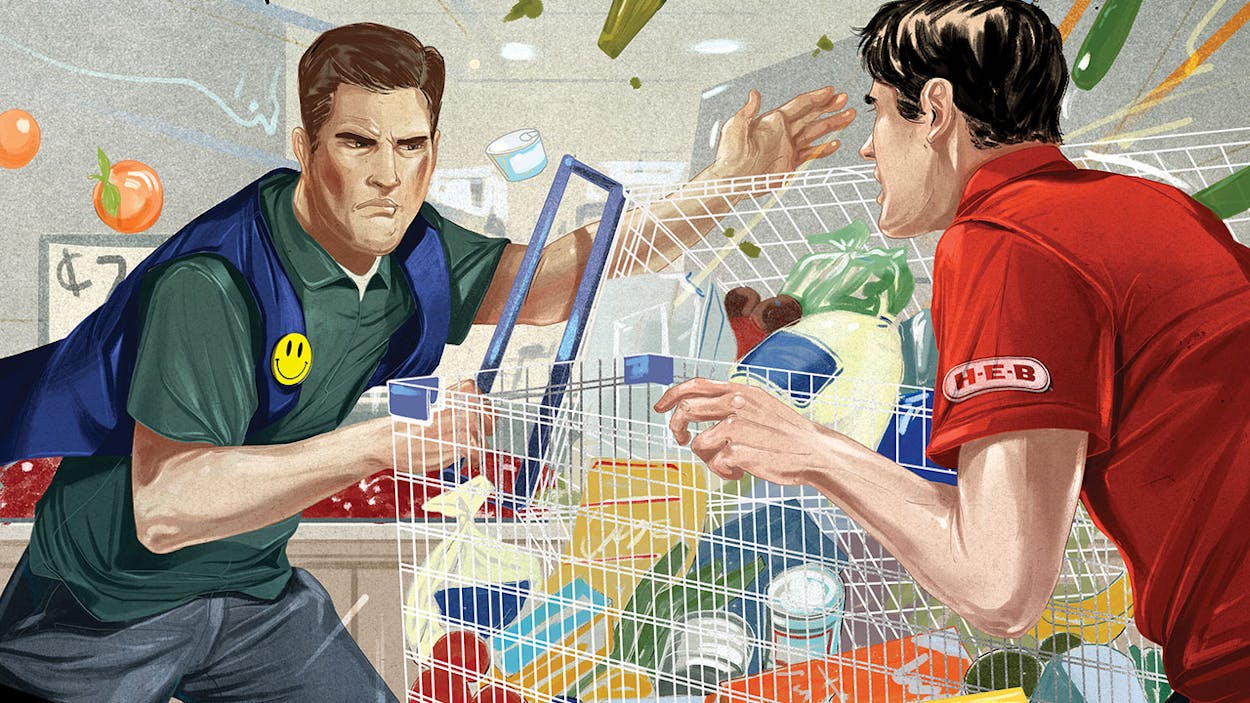

Groceries are the most competitive area of retailing, and nowhere is that more apparent than in Bexar County, where H-E-B and Walmart are engaged in an intense game of real estate one-upmanship. Last year, H-E-B remodeled its 97,000-square-foot store in Universal City, only to have Walmart snap up a thirteen-acre site right next door, where it plans to open a 182,000-square-foot Supercenter this summer. Twenty-five miles away, in Spring Branch, Walmart just finished building another Supercenter, catty-corner from an H-E-B Plus. It even bought an old H-E-B store on San Antonio’s northeast side and converted it to its small-scale Neighborhood Market format. In total, Walmart added a dozen stores in San Antonio during 2014 and 2015 and six more so far this year. Not to be outdone, H-E-B opened or remodeled 12 San Antonio stores, capping things off with a 182,000-square-foot megastore near SeaWorld.

Walmart’s land grab is part of a major push by the global retailing juggernaut into the home turf of Alamo City stalwart H-E-B, a 110-year-old family business that has become a Texas powerhouse over the past 40 years. H-E-B has made it clear that it won’t be intimidated: between 2009 and 2014, Walmart snapped up 250 acres of property for about $123 million, and H-E-B matched that land grab acre for acre, according to an analysis of Bexar County land records by the San Antonio Express-News. While it’s too soon for H-E-B to declare victory, Walmart remains a distant second; last year, H-E-B controlled 48 percent of the San Antonio market, compared with Walmart’s anemic 28 percent. It’s unusual for Walmart to be trailing in a market it set out to dominate. “Walmart has learned that it can’t win every time,” says David Livingston, a supermarket analyst and principal of the consulting firm DJL Research. “H-E-B pretty much owns the market.”

Or does it? In 2015 Walmart’s share of the local grocery market rose nearly five percentage points, while H-E-B’s slipped about three points. Those are the sort of numbers that will keep both parties on their toes.

Groceries may be among the lowest-margin segments of the retail market, but it’s a steady business—even in a recession people buy food—and the competition in Texas is fierce. As H-E-B and Walmart slug it out in San Antonio, they face mounting competition statewide from the likes of Whole Foods, new arrival Trader Joe’s, Kroger, Randalls, Tom Thumb—the last two owned by Albertsons—and smaller chains such as Aldi, Sprouts, and Brookshire Brothers. Earlier this year, Kroger, which has 203 stores in Texas, warned that sales growth could be the worst in more than a decade, in part because the field has gotten so crowded.

Walmart, which competes not just in groceries but across the retailing spectrum, has struggled too. In January it announced plans to close 154 stores across the country; Texas had the most closings of any state (29), in part because of a weakening economy brought on by lower oil prices. At the same time, the giant retailer hasn’t stopped expansion. It will add 25 new locations here this year. And groceries are an increasingly important part of that growth strategy, accounting for more than half of its U.S. sales last year.

Walmart got into the grocery business in 1987, when it opened its first Hypermart USA, in Garland. Hypermart was a French-inspired hybrid of a grocery and a Sam’s Club—the size of four football fields—that included a health food store, a deli, a tortilla factory, a shoe repair shop, a bank, and a video rental outlet, for good measure. The format had its problems; cooling such a large space in the middle of the Texas summer was costly, and the parking lots were overcrowded. Walmart refined the concept into its Supercenter format, and it continued to focus on groceries, opening its first Neighborhood Market in 1998.

In parts of Texas, Walmart is clearly the big player. In Dallas–Fort Worth, where H-E-B has a minimal presence, with just five of its Central Market–branded stores, Walmart controls 27 percent of the market, almost twice as much as the next biggest competitor, Kroger. But move farther south, and H-E-B asserts its dominance. In addition to its lead in San Antonio, it maintains a commanding lead in Austin—46 percent to Walmart’s 19 percent—and in Houston, H-E-B actually leapfrogged Walmart and Kroger last year to become the market leader, with 21 percent, compared with Walmart’s 20 percent.

In San Antonio, though, H-E-B’s heritage runs particularly deep. In 1905 Florence Butt borrowed $60 to open Mrs. C. C. Butt’s Staple and Fancy Grocery on the ground floor of her Kerrville home. (Today that space houses a diner, which proudly boasts of its historic legacy.) Two decades later, her son, Howard E. Butt, took over the business, added stores in Del Rio and Laredo, and moved the company’s headquarters first to the Valley and then to Corpus Christi. Rebranded H-E-B, for Howard’s initials, the company expanded from neighborhood grocery stores into supermarkets in the fifties, and in 1971 Howard handed the company over to his son Charles, who had been working in H-E-B stores since he was eight years old. (He started as a sacker and worked his way up to checker four years later.)

Charles moved the headquarters to San Antonio in 1985 and expanded into different market sectors with Mi Tienda, which was aimed at Hispanic shoppers; Central Market, which was intended to stave off Whole Foods; and H-E-B Plus, which, like Walmart, offers general merchandise as well as groceries. It pushed into Mexico in 1997, crossing the border even before it opened a store in Houston or Dallas. Today, H-E-B has 307 supermarkets in Texas and 53 in Mexico. It’s one of the biggest private companies in the country and one of the top twenty retailers, with more than $23 billion in sales, according to the National Retail Federation. (H-E-B declined to make executives available for this story, saying, “We are a fairly humble culture.”)

Walmart, of course, has modest small-town beginnings too. It started with Sam Walton’s single five-and-dime on the square in Bentonville, Arkansas, and, as of January, had $482 billion in annual global sales and more than 4,500 U.S. locations. It’s so huge that it increased sales in the past four years by more than H-E-B takes in annually; picture Walmart adding a company the size of H-E-B

in 48 months and you get the basic idea.

Companies that reach Walmart’s size typically confront a principle known as the law of large numbers, which basically means that the bigger a company gets, the more difficult it is to maintain its growth rate. Walmart, however, has confounded this law by developing a strategy known as the productivity loop. As Walmart has grown, its scale enables it to get lower prices from suppliers. This boosts its productivity—it sells more with less overhead—which in turn fattens profit margins. The company then puts a significant portion of its profits back into its operations so that it can lower prices even more. It’s a perpetual motion machine of profitability.

Long before Walmart starting pushing into South Texas, H-E-B began studying the company’s success, and it adapted the productivity loop to its own business. “They anticipated Walmart’s arrival and they cut the advantage that Walmart has over every other retail chain,” says Leigh McAlister, a marketing professor at the University of Texas and co-author of Grocery Revolution: The New Focus on the Customer. “H-E-B is six steps ahead of everybody else. South Texas is the only place that Walmart hasn’t been able to just roll into and dominate.”

While the productivity loop works in all aspects of retailing, it has unique benefits in groceries. For example, H-E-B puts an emphasis on working with local suppliers, which cuts down on transportation costs, allowing H-E-B to lower produce prices and turn over inventory quickly, which keeps its fruits and vegetables fresh—a key to attracting customers. (And while it may be churning much of its profits into lowering prices, the company still adheres to Charles Butt’s long-standing policy of donating 5 percent of pretax earnings to charity and millions of pounds of groceries to local food banks each year.)

H-E-B has a few other things working in its favor. Its century-deep Texas roots make it an iconic brand that Texans love to root for, like Blue Bell, Whataburger, and Dublin Dr Pepper. Because the company remains privately held, it can reinvest in its business without worrying about meeting quarterly earnings forecasts or pleasing investors. (Late last year, it granted stock equal to about 15 percent of the company to 55,000 employees.) Since it opened its San Antonio milk plant in 1976, H-E-B has relied on its own manufacturing—rather than private labels produced by other companies—for its store brands, which are popular with customers. And its corporate staff is stocked with MBAs—unusual for a regional grocer—who churn out market research that helps H-E-B identify customer preferences. Walk into any H-E-B and you’ll find Texas-specific products such as jalapeño cheeseburgers, freshly pressed and ready to throw on the grill. The chain also tailors its product offerings by zip code, reflecting the preferences and economic demographics of each neighborhood in which it operates, says Kelli Hollinger, the director of Texas A&M’s Center for Retailing Studies. Known as store localization, the tactic has given H-E-B a particularly strong following among Hispanic consumers, whom it has long cultivated.

H-E-B may have held its own by imitating Walmart (almost twenty years after Walmart launched its “Every Day Low Prices” slogan, H-E-B adopted the uncannily similar “Low Prices Every Day”), but Walmart isn’t above copying H-E-B either. Since moving into San Antonio, it has been emulating H-E-B in its produce aisles and working with local suppliers. “We are very excited about our progress and the work that we’ve done in fresh produce,” says Uli Correa, Walmart’s regional general manager for South Texas. Walk into one of the Walmarts he oversees and you might find Texas sweet onions and Fredericksburg peaches.

After all, H-E-B may be a scrappy competitor, but Walmart really doesn’t like to lose—and it has the financial resources to stay in the market as long as it wants. “H-E-B can’t put Walmart out of business or drive them out of the market,” says McAlister. “Walmart could lose money in South Texas from now until eternity and it wouldn’t matter.”