Q: I grew up in the forties and fifties, when the rule in my grandma’s Texas kitchen was that the men ate first, waited on by the women, then the women and children dined. Everyone seemed happy with the arrangement. But heavens to Betty Friedan, nowadays the experts say all family members should commune together or the family will disintegrate. Does the Texanist know how this age-old dining order started, where it is still practiced, and if the custom will end up relegated to the list of Quaint Practices of Yesteryear?

Billie Leyendecker, Brownsville

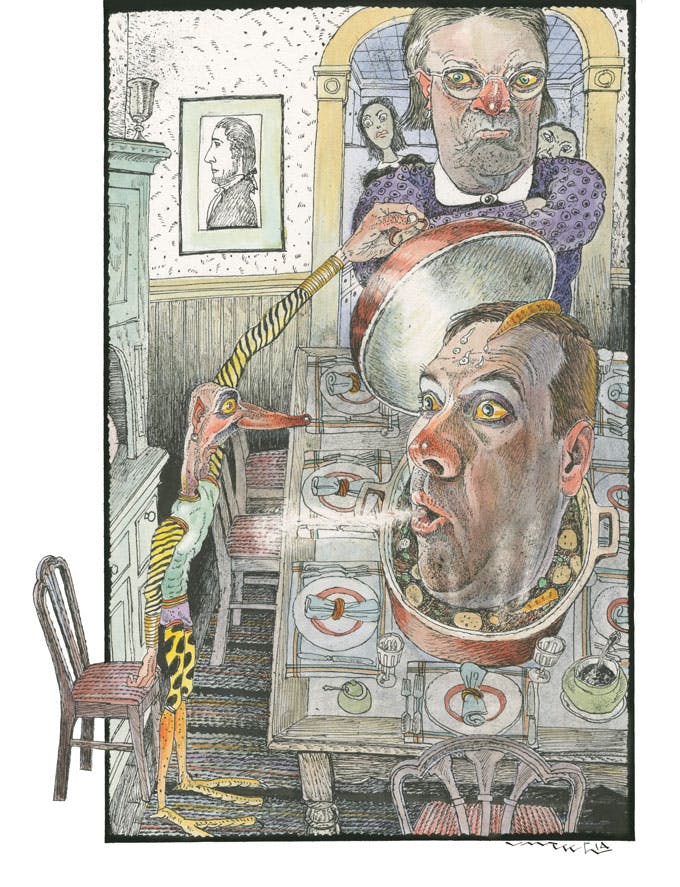

A: Please correct the Texanist if he is wrong (for your convenience, he has included a self-addressed, stamped envelope with your July issue), but he seems to be picking up a smidge of longing in your missive—a bit of a pining for what he suspects you might consider to be the “good ol’ days.” If this is the case, Ms. Leyendecker (the Texanist checked, and Billie assures him that she is, indeed, of the female persuasion), you have befuddled the Texanist, who would have bet the heaping plate of homemade buttermilk biscuits that he himself just pulled out of his own oven that the womenfolk would have been somewhat less content with the “rule” in your dear grannie’s kitchen than the menfolk. But perhaps the menfolk weren’t good company. Or perhaps the womenfolk just preferred the company of the children and themselves to that of the menfolk. The Texanist is now curious about the particular dynamics of your family. Regardless, the setup would seem to suit a larger extended family better than, say, a simple nuclear family, a unit whose makeup caps the number of both womenfolk and menfolk at one. Suppertime would be a mightily quiet time for Dad in this scenario. With whom would he banter? Who would pass the peas?! As to precisely how, when, and where this custom originated, the Texanist can’t say for sure, as his formal training on the subject ended on the last day of Anthropology 101 during his early college period, which was a long time ago. But even as old-timey-feeling as this mealtime system is, it is probably still practiced in some families, although the Texanist could name for you not a single one. The Texanist does know this, however: if he were to ever let out an utterance in his home that sounded anything like “The Texanist requires another pork chop! Serve the Texanist his additional pork chop now,” it’s highly likely that that chop would be delivered to him upside his head—along with the skillet in which it was cooked, the entire jar of applesauce with which it was to be sided, and the tall glass of cold milk with which it was to be washed down.

Q: As a loyal Texan I have struggled the past eighteen years having to live in moist, gray Portland, Oregon. When the younger of my two children graduates from high school in five years and moves on to college, my wife and I will have the freedom to go and do whatever we please. Texas is still my home, and I would move back quick, but my wife will have none of it. Tex-Mex is nonexistent in the Northwest, and sadly, barbecue is a peculiar mash-up of North Carolina– and Tennessee-born vittles. The closest I can get is a pull of Shiner Bock. So, what’s a Texan removed from Texas to do, knowing he can’t come home? Help me, Texanist, you’re my only hope.

Derek Welch, Portland, Oregon

A: The Texanist thanks his lucky stars every day for the tremendous fortunateness that has befallen him in his lifetime. So abundant are these blessings that there is simply neither the time nor the space to list them all here. But right there near the tip-top of the list of these things for which he is thankful would be his own father, a sagacious man who imparted a great deal of invaluable wisdom to a young Texanist during the inelegance of his formative years. In particular, there is one bit of that fine advice that is pertinent here: the Texanist’s dad always counseled him to do as he had done and find a sweet-smellin’ West Texas gal for a mate. You, apparently, were not so lucky as to get such good guidance from your own father, and now you find yourself thousands of miles away from home, with an ornery, non-Texan spouse who cannot relate to your homesickness. No offense intended. Alas, you didn’t come to the Texanist for help with irreparable marriage problems. What’s done is done. You came to him a Texan in exile looking for a way home, be it figurative or real. Well, the Texanist has a fix for you. That young half Texan of yours—the one who is due to graduate from high school in five years—may not know it yet, but he is going to seek his further learning at one of Texas’s many superb institutions of higher education. Once Master Welch is here, his mother will be up for frequent visits, which in turn, be he a Sul Ross Lobo in Alpine, a Stephen F. Austin Lumberjack in Nacogdoches, or a West Texas A&M Buffalo in Canyon, will cause her to view the Lone Star State even more favorably than Davy Crockett, who, after feasting his eyes on just a small swath of the splendor that is Texas, famously wrote back home with this observation: “I must say as to what I have seen of Texas it is the garden spot of the world. The best land and the best prospects for health I ever saw, and I do believe it is a fortune to any man to come here.” Your long-awaited repatriation will soon follow. Until then, the Texanist recommends you have another Shiner.

Q: I first wrote to you in February 2012. My husband and I were concerned about appropriately using “Texan” phraseology, having only resided in Texas for two years. Well, I am pleased to report that after five years in full submersion, we can throw down a “fixin’ to” with the best of y’all. But as life would have it, we are moving back to Wisconsin. Our youngest child has a Texas birthright, but the other three only have five years to draw on. Which Texas qualities are of utmost importance to retain in our offspring?

Kathy Steinke, Tomball

A: Well, of course, Mrs. Steinke—the Texanist remembers. He was happy to be able to help back then, and he’s glad you’ve returned. It appears that you and fellow advice-seeker Derek Welch are sharing some sort of Twilight Zone–style, alternate-universe moment. He, Texas-born, is gone and aching to return, and you and your family are Midwestern transplants (with the exception of the little one) reluctantly headed back north. Please, tell the Texanist that your young one’s name isn’t [dramatic pause] Derek Welch! The Texanist jests. Although the Steinkes were here for only five short years, y’all will not soon forget your time in Texas. So much has happened. Little Tex Steinke was brought into the world here, after all. But even with such an abbreviated Texas upbringing, trust the Texanist when he tells you that all of the Steinke children will be leaving the state with a wealth of Texas-y attributes. Among these, and in no particular order, are their newfound proficiencies with manners, whittling, spitting, carnivorousness, horsemanship, gunmanship, pickup trucksmanship, and a healthy respect for things both jagged and poisonous, not to mention a high tolerance for heat. All of these traits will serve them well throughout their lifetimes, no matter where they end up. Happy trails, Steinkes. The Texanist wishes y’all the best and awaits your next letter.

The Texanist’s Little-Known Fact of the Month: The highest mercury reading ever recorded in Texas is a whopping 120 degrees Fahrenheit, which has occurred twice: first, in Seymour on August 12, 1936, and then again nearly sixty years later, in Monahans on June 28, 1994. Who wants an iced tea?