When the weather gets warm, Texans start thinking about what to read at the beach or maybe on the porch of a Colorado getaway. This year, thanks to the effects of the coronavirus pandemic, many of us have even more time on our hands to dive into a book. Here’s a selection of new Texas works—and a few old ringers—that might edify or entertain you while you’re cooped up.

Essay

How ‘Passage’ Author Justin Cronin Became a Lifelong Catastrophist

I’ve been waiting for this to happen since I was twelve years old.

It began with a book. How this book made its way to me I can’t recall. No adult would have suggested that I, a child, read such a thing; neither would it have come to me from a peer, since most of my peers had no interest in books of any kind. The one thing I know for sure is that it came from the town library—the memory is steeped in the sensory package of the place—and I’d like to think I didn’t so much find it on the shelves as accept its fated leap into my hands. Read More

Review

Hill Country Hauntings

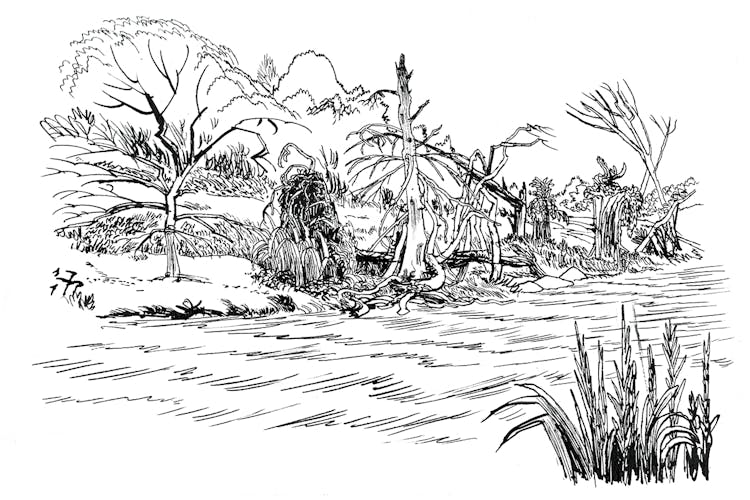

The “here” in the title of Austin native Nancy Wayson Dinan’s Things You Would Know If You Grew Up Around Here (Bloomsbury, May 19) is the Texas Hill Country—specifically, that idyllic, rough-hewn region as it stands in the aftermath of 2015’s historic Memorial Day floods. This picturesque debut novel follows eighteen-year-old Boyd Montgomery as she traverses the banks of the overflowing Colorado River in search of her missing best friend, Isaac. That Boyd has an almost supernatural ability to feel others’ pain is only one of several mystical elements in this magically realistic odyssey. On her journey she encounters ghosts from various eras of the region’s history, such as a young German boy who froze to death during a bitter winter in the early twentieth century and a giant, armadillo-like glyptodont from the Pleistocene age who watches Boyd one night as she sleeps beneath a pin oak tree. It’s as if the storm has washed away not only concrete bridges and centuries-old cypress trees but also the barrier that separates Texas’s past and present. Supporting characters such as the hippie neighbor who quit Austin when it got too big for its britches and the ill curmudgeon living at the end of a dirt lane called Nameless Road will feel authentic to readers already familiar with “here” and seem real to those who aren’t. Periodic descriptions of the sorts of “things” that the title refers to—flash floods, the mythical lost San Saba mine, the tradition of painting a patch of fence post purple to ward off trespassers—add still more texture to Dinan’s detailed portrait of a part of Texas whose novelistic potential few authors have tapped. —Emily McCullar

Review

Coming of Age in San Antonio

Sometimes an imperfect book is well worth reading. That’s the case with The Duchess of Angus (Trinity University Press), a previously unpublished novel written about six decades ago by the late Margaret Brown Kilik, an artist who lived in San Antonio as a young woman during World War II and then left, eventually settling in New York City. Duchess, Kilik’s only novel, is a semiautobiographical coming-of-age story about Jane Davis, a young woman who returns home to San Antonio from a Midwestern college in 1943 and befriends another young woman, the beautiful, worldly Wade Howell. The two wind up as roommates, sharing secrets and loves as each struggles to choose between the life she wants and the life others want for her.

The book is, clearly, a first draft of a first novel. But even so, the San Antonio of those days is vividly drawn. Kilik’s city is limited mostly to the old downtown area and the officers’ quarters at Fort Sam Houston, but those renderings are pitch-perfect; she deftly evokes the thickness of the air along the River Walk and the striving salesgirls at Joske’s department store. It’s a shame Kilik gave up on writing, and San Antonio, so soon. —Mimi Swartz

Essay

The Secret History of the Texas Rangers

Your opinion of the Texas Rangers likely reflects something about how you or your ancestors first entered into the epic tale of the Lone Star State. If you’re the descendant of Anglo settlers who squared off against fierce indigenous resistance and recalcitrant, long-settled Tejanos, then you probably regard the Rangers as the venerable knights-errant of the sprawling Central Plains and southern brush country, the guardians of civil order on the lawless frontier, ever dutiful in their white cowboy hats, ringed silver-star badges, and Colt .45 sidearms. If your forebears were Tejanos whose colonial patrimonies were stolen, often violently, then you may believe the early Rangers to have been nothing more than bloodthirsty thugs for hire, lawless instruments of white supremacy. Read More

Playlist

Go-Go’s Bassist Kathy Valentine Remembers the Sounds of 1970s Austin

In the seventies, teenagers galvanized by rock and roll noodled around on guitars, sang into hairbrushes, and dreamed about becoming stars. Kathy Valentine lived the real thing. By the time she was sixteen, the Austin native and future bassist for the Go-Go’s had sat in with roots rocker Doug Sahm onstage, hitchhiked to see ZZ Top perform at a mud-soaked outdoor festival, and become a fixture at Stevie Ray and Jimmie Vaughan shows. “While other teen girls shopped for prom dresses, I gazed up at Freddie King onstage, sweat pouring off his face, taking me on a tail-spinning ride of hot-rod, gutted guitar playing,” she writes in her new book, All I Ever Wanted: A Rock ’n’ Roll Memoir (University of Texas Press). Read More

Review

Ana and Her Sisters

Dallas writer Samantha Mabry’s new young-adult novel, Tigers, Not Daughters (Algonquin Young Readers), tells a tale of grief, nosy neighbors, abusive boyfriends, drunk fathers, and ghosts. But more than anything, it’s a story about sisters.

Before the novel begins, eighteen-year-old Ana Torres slips while sneaking out of her second-story bedroom window and falls to her death. Her sudden demise has a huge impact on her quiet San Antonio neighborhood, a part of Southtown still home to established Mexican American families where everyone seems to know everyone else’s business. Where was Ana going? Did a car speed away right after she fell? What did the boys across the street see?

A year after Ana’s death, questions are still haunting the surviving Torres sisters. After their single father slips into anger and alcoholism, Ana’s three younger sisters are left to essentially fend for themselves. The oldest, Jessica, becomes the family’s main breadwinner and emotional glue, but she’s dealing with a possessive boyfriend who has a complicated history with the family. Iridian wants to retreat into her reading and her secret journals. The youngest, Rosa, is quiet and wise beyond her years; as Mabry writes, her heart “was crafted to ease the suffering of others.”

The chapters alternate among each sister’s point of view, and each sibling is a distinct personality; Jessica’s weariness is complemented by Rosa’s mysticism, and Iridian’s anger pulses through Tigers, Not Daughters. This is the kind of book where you feel deflated as one chapter comes to an end—Don’t go, Rosa!—but then rejoice when the narrative switches to a different sister.

And then, Ana comes back. Or something does. The boys across the street see Ana standing in her yard, Jessica sees a hand pressed against the shower curtain, and Rosa starts hunting an escaped hyena from the zoo—but what if that hyena is actually her sister?

Mabry is the author of two previous YA novels, including All the Wind in the World, which was long-listed for the National Book Award in 2017. In her latest work, she offers a narrative that’s at once a ghost story and a realistic family drama, without compromising either genre. The Torres sisters are as vividly rendered as—and more powerful than—the domestic and supernatural forces gathered against them. —Richard Z. Santos

Essay

The Great Texas Novel About the Spanish Flu

There’s a scene early in Katherine Anne Porter’s 1939 novel Pale Horse, Pale Rider in which two young lovers take a walk outside the rooming house where they’ve met and enjoy the beautiful fall afternoon. As Adam and Miranda exchange the charged and pleasant small talk of the recently enamored, their stroll is interrupted by one funeral procession, then another.

“It seems to be a plague,” Miranda remarks, “something out of the Middle Ages. Did you ever see so many funerals, ever?”

Reading this passage in 2020, one could be forgiven for wanting to shake Adam and Miranda by the shoulders and shout, “Social distancing! Use hand sanitizer! And for God’s sake, don’t kiss!” Read More

Q+A

‘Valentine’ Writer Elizabeth Wetmore’s Texas Roots

For her riveting first novel, Valentine (HarperCollins/Harper), Elizabeth Wetmore returned to her West Texas hometown of Odessa. The book, which debuted at number two on the New York Times hardcover fiction best-seller list in April, follows the repercussions of an especially brutal sexual assault on a teenage girl on Valentine’s Day in 1976. Set against the oil country’s unsparing landscape, the story is told from the perspectives of seven girls and women, many of whom live near one another on a street called Larkspur Lane. A graduate of the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, Wetmore has had short stories published in literary journals such as Epoch, the Kenyon Review, and the Colorado Review. The 52-year-old writer lives in Chicago with her husband and teenage son. Read More

Review

Friday Night Plights

In the post–Friday Night Lights cultural landscape, if a work of fiction set in small-town Texas opens with a high school football game, you know something is about to go horribly awry. The Bright Lands (Hanover Square Press, July 7), a debut mystery novel by Waco native John Fram, is no exception. It begins with a big game, and sure enough, beloved quarterback Dylan Whitley soon goes missing, leaving his older brother, Joel, worried sick. A financial analyst visiting from Manhattan, Joel hasn’t set foot in his hometown of Bentley in years, and being there puts him back in touch with the shame he felt growing up as a closeted young gay man in a priggish Baptist community. As he attempts to find out what happened to his brother, Joel learns that beneath this sanctimonious society lies a world of fear, depravity, and abuse.

What makes the book sing are its ensemble characters, like the sheriff’s deputy, who was Joel’s first (and only) girlfriend, and Dylan’s friends and classmates. Fram moves his narrative through all their perspectives, revealing clues with a cinematic pacing that makes Bright Lands an addictive and provocative modern whodunit. —Emily McCullar

This article originally appeared in the June 2020 issue of Texas Monthly with the headline “What to Read Now.” Subscribe today.

- More About:

- Books