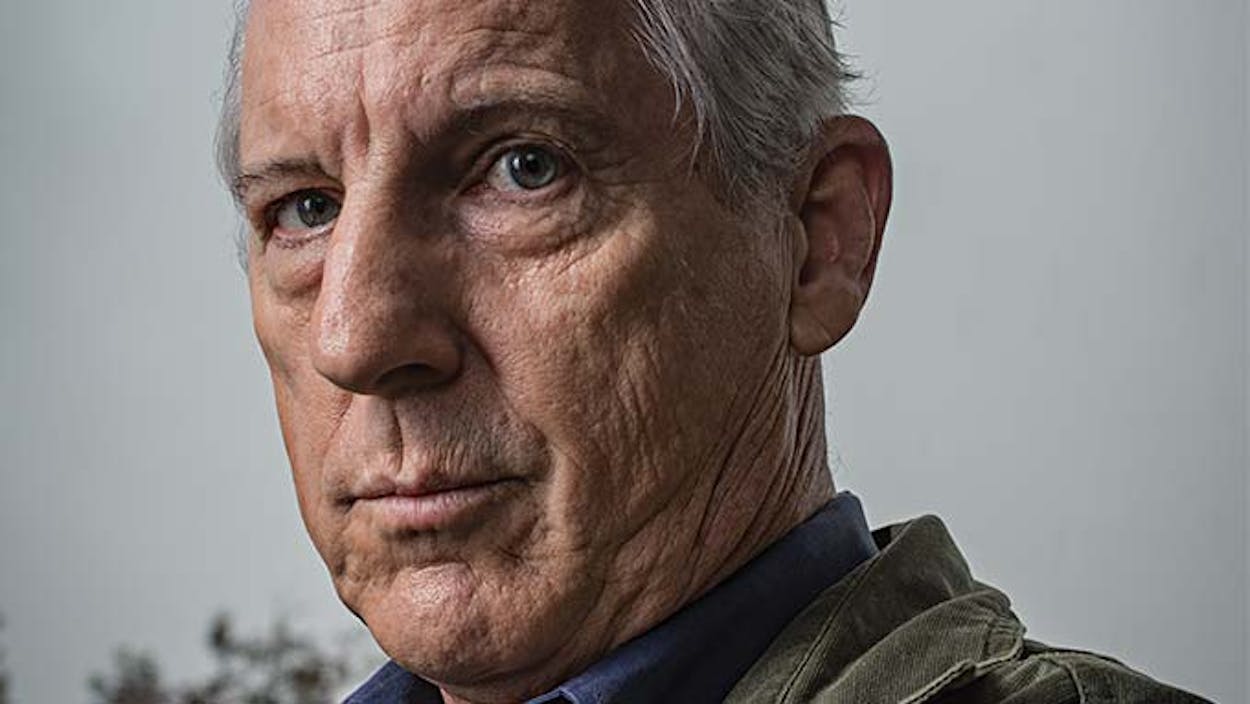

There are 65 acting credits listed for Marco Perella on the Internet Movie Database, some of them in high-profile productions like JFK, Lone Star, and Friday Night Lights. But the characters he’s played tend to be identified on IMDb by labels like “Cab Driver,” “Townsperson,” “2nd Young Guy,” “Preppy Customer,” “Starbucks Guy,” “Skinny Dude,” and “Jester (scenes deleted).” The Austin actor made a typically brief appearance in a television movie I wrote a dozen years ago, and I congratulate myself on having gone to the extra effort of providing his character, a psychopathic drifter in nineteenth-century Missouri, with an actual name.

Not that I really needed to bother. Perella is so comfortable with obscurity that he wrote a book in 2001 called Adventures of a No Name Actor, a very funny memoir about a regional actor’s frantic scramble to make a living by grabbing bit parts in big movies and medium parts in “wretched little TV movies” (hey, no offense taken!).

This year, however, thanks to his performance as the evil stepfather in Richard Linklater’s Boyhood, he’s bumped himself up to a new level of identifiability, if not exactly fame. “It’s always the same,” he says. “People come up to me and say, ‘I’m sorry, but I just have to tell you what an asshole you are.’ ”

Perella joined the cast of Boyhood in the third year of its twelve-year production. He plays Bill Welbrock, the college professor who marries the divorced mother of Mason, the boy whose growing-up years the movie chronicles with such uncanny fluidity. Bill seems at first to be the ideal antidote to Mason’s own guileless, unrooted father. He’s kind and focused, fully committed to his new blended family. But from almost the first of Perella’s sixteen scenes, filmed over the course of three years, you have a nervous feeling about this guy. It’s not just the flash of anger he displays in a restaurant when he takes a video game away from his son, or the slightly imperious, offhanded way he orders a second bottle of wine. It’s a look of twitchy suspicion on his face, the suggestion that beneath the paternal affability there’s a boiling magma chamber of hostility.

In his book, Perella describes himself as being a “fairly pleasant-looking person” who nonetheless can “manage to look like a psychotic mole rat.” Boyhood tracks the way his open-faced everyman features begin to scrunch into aggrieved martyrdom. Bill is a mean drunk, stewing with outrage, morphing from benevolent husband and father to sadistic suburban martinet.

Because of the way it was conceived, Boyhood is a visionary departure from almost every other movie ever made, but it has the same aversion to plottedness and the same pilgrims’-way narrative strategy that have distinguished Linklater’s signature works. Whenever Perella is onscreen, however, the movie’s metabolism spikes. Bill’s jarring presence is crucial; it injects danger and consequence into what might otherwise have been just a novel excursion down the river of time.

“Rick just called me and asked if I’d do it,” Perella says. He’s had small parts in Linklater films like A Scanner Darkly and Fast Food Nation, and he assumed this movie was “a little side project. I could not grasp how it was going to affect people once it was done.”

“It’s extraordinary,” Linklater says of Perella’s performance. “Marco is amazing in the way he was able to feel the trajectory of that character. The character was there conceptually, of course, but Marco really fleshed him out. He just really, really brought it.”

Perella appraises his performance with forensic modesty. “A hundred actors could have done that. There’s a kind of alcoholic—everybody has seen them, I’m not figuring it out for the first time—who has to blame other people for his deficiencies. There are actions that the director needs you to do, and from those actions—like hiding a bottle of whiskey in the laundry room—you can get a lot. The rest of it was just instinct, just going with it.”

Maybe he’s right and a hundred actors could have done it, but Perella’s skill and his career-long semi-visibility endow his scenes with a “Who’s that guy?” charge, the sense of witnessing an accomplished but little-noticed actor finally converging with an indelible part.

As to who that guy is, he’s the 65-year-old Houston-born son of Theosophist parents, followers of the Russian philosopher Helena Blavatsky. He grew up in Meyerland, back in the days when it was a raw suburb and dead coyotes were still to be seen strung up on the fences of neighboring ranchers. Perella’s father owned an advertising agency, but the grubby demands of achieving worldly success left him feeling “morally besmirched,” and he searched for deeper meaning in an upstairs meditation room. Later, as a manufacturer’s rep, he hit the road for six months out of the year and brought his family along with him. Perella and his sister were homeschooled in the backseat as they were driven across the country. When Perella was in the fifth grade, his father built a house in Prescott, Arizona, determined to settle there and write and ponder the meaning of existence. But the cold bothered him so much he moved the family to Hawaii, which didn’t work out that well either, because the noise of the waves on the beach disturbed his meditations.

Perella ended up graduating from high school in Phoenix. After dropping out of Stanford, he moved to Taos and spent ten years working construction and fighting forest fires. He hadn’t thought of himself as an actor until a friend talked him into auditioning for the part of Riff in a local production of West Side Story. One night Russ Tamblyn, who had played the part in the film version, showed up backstage with Neil Young, Dean Stockwell, and Dennis Hopper.

“They all told me how good I did. That gave me a real charge and I decided, goddammit, I’m going to be an actor.”

He knew there wasn’t enough acting work to make a living in Taos, so he moved to Austin, where he’d heard there were paying theater companies. His girlfriend, Diane, also an actor, followed him to Austin with her two children. They got married and got enough jobs and set down deep enough roots that the idea of moving to New York or Los Angeles never made a compelling case for itself.

“I played Santa, emceed company parties, did low-rent commercials, industrial training films, bad theater, singing telegrams, Renaissance fairs, clown gigs. At a certain point, I got cast in some higher-profile roles that I could have gone to L.A. on and probably gotten an agent. Thing was, by that time I was already in my early thirties. I wasn’t a leading man and I wasn’t quite a character actor either. The truth is, whenever I thought about moving to L.A., I kind of cringed. I didn’t have that fame bug, that unquenchable thirst for that thing. It was just empty calories to me.”

Though he gives an award-caliber performance in Boyhood, it’s unlikely that it will stir up a Best Supporting Actor nod when the Oscar nominations are announced, on January 16. Perella is too much of an outsider, too much of an unknown. And he’s definitely not overinvested in the expectation that the role is going to be a big break. For one thing, he finished filming his part relatively early in the twelve-year production, so he might be a little hard for a casting director to get a bead on. He’s eight years older than the 2006 model Marco Perella that appears in the film. His hair is a little whiter, his face is a little fuller, his puzzlement about the human hunger for fame and celebrity a little deeper.

“I’m still getting my share of things, but nobody’s called me from L.A. and said, ‘Look, we have to have you in our movie, because you’re such a good asshole.’ ”

Meanwhile, he’s just finished filming My All American, a biopic about the UT football player Freddie Steinmark (“I play the doctor who had to cut off his leg”). It’s the sort of role that would have come his way in the pre-Boyhood days, and he has a Blavatskian air of karmic contentment about that. When you’re a committed actor who doesn’t care about empty calories, the work doesn’t need to flood in, it just needs to keep flowing.