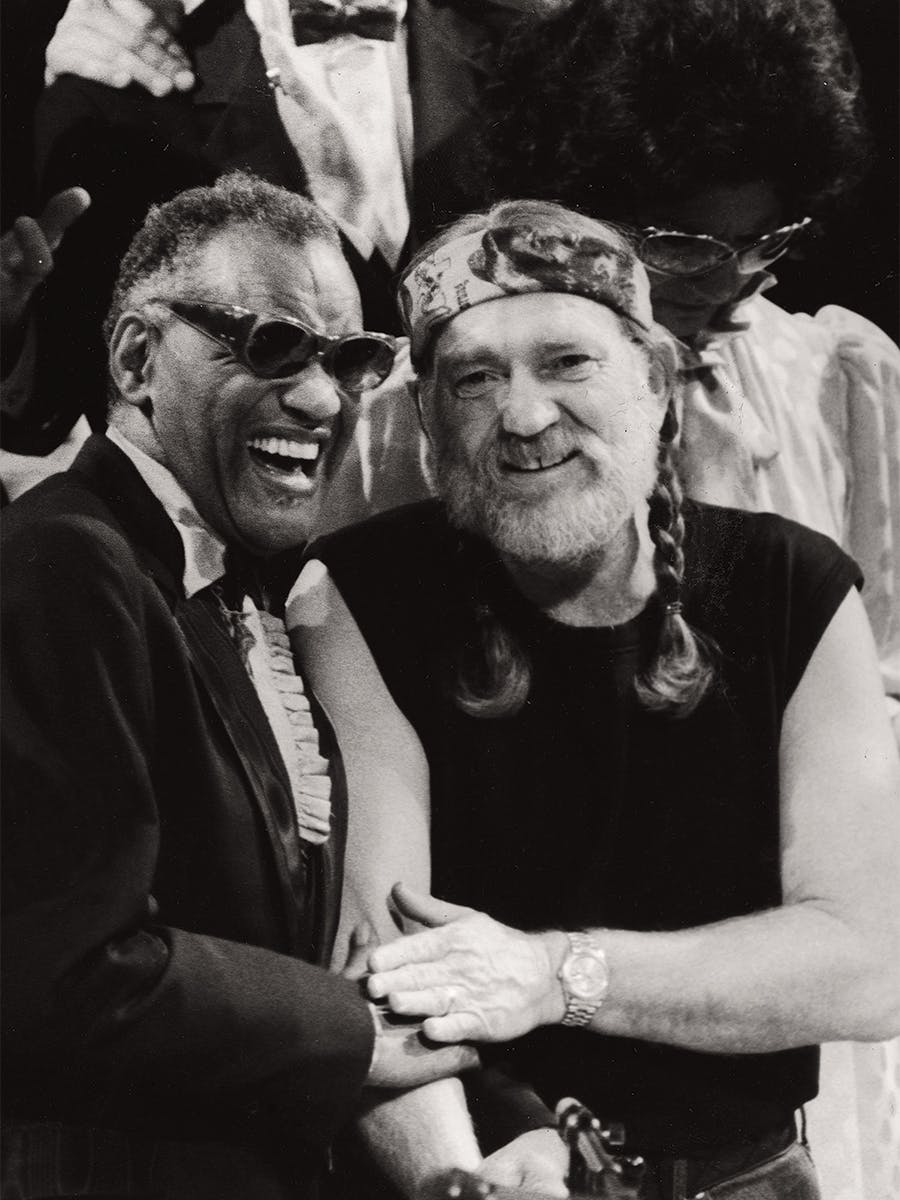

You expect outlaws to ride bravely into alien territory, but that still doesn’t prepare you for Willie Nelson’s wholesale robbery of the Great American Songbook. Just listen to his version of “Georgia on My Mind,” off his 1978 album Stardust, and ask yourself how he managed to confiscate one of Ray Charles’s signature songs. Maybe he was inspired by Charles’s own inroads into country music, or maybe it was payback for same; either way, somehow, the future official song of the state of Georgia got stolen by a Texan.

And Willie didn’t stop there. Consider his ease in taking over Duke Ellington’s big band–era hit “Don’t Get Around Much Anymore” or the Tin Pan Alley classic “All of Me,” an ode to romantic surrender that Billie Holiday all but owned. These things shouldn’t be allowed. Great American Songbook? It’s more like the Great Train Robbery.

But it’s the laid-back way Willie pulls all this off that’s most impressive. He sounds so natural and relaxed on his recording of “Georgia on My Mind” that he might be talking in his sleep, relating a lovely dream. His tempo is an oh-so-lazy 65 beats per minute, slower than most human heartbeats—and certainly slower than Louis Armstrong’s, Ella Fitzgerald’s, and Charles’s best-known versions. And Willie’s phrasing adds to the sweet and slow musing promised in the song’s title. Instead of Charles’s elaborate declamations, filled with bluesy bent notes, Willie delivers a little quiver here, a wistful hesitation there. When he comes to the phrase “no peace I find,” his elongation of the line isn’t mere ornamentation; the listener actually gets a sense of his search for that elusive peacefulness. Somehow, understatement becomes the voice of authority.

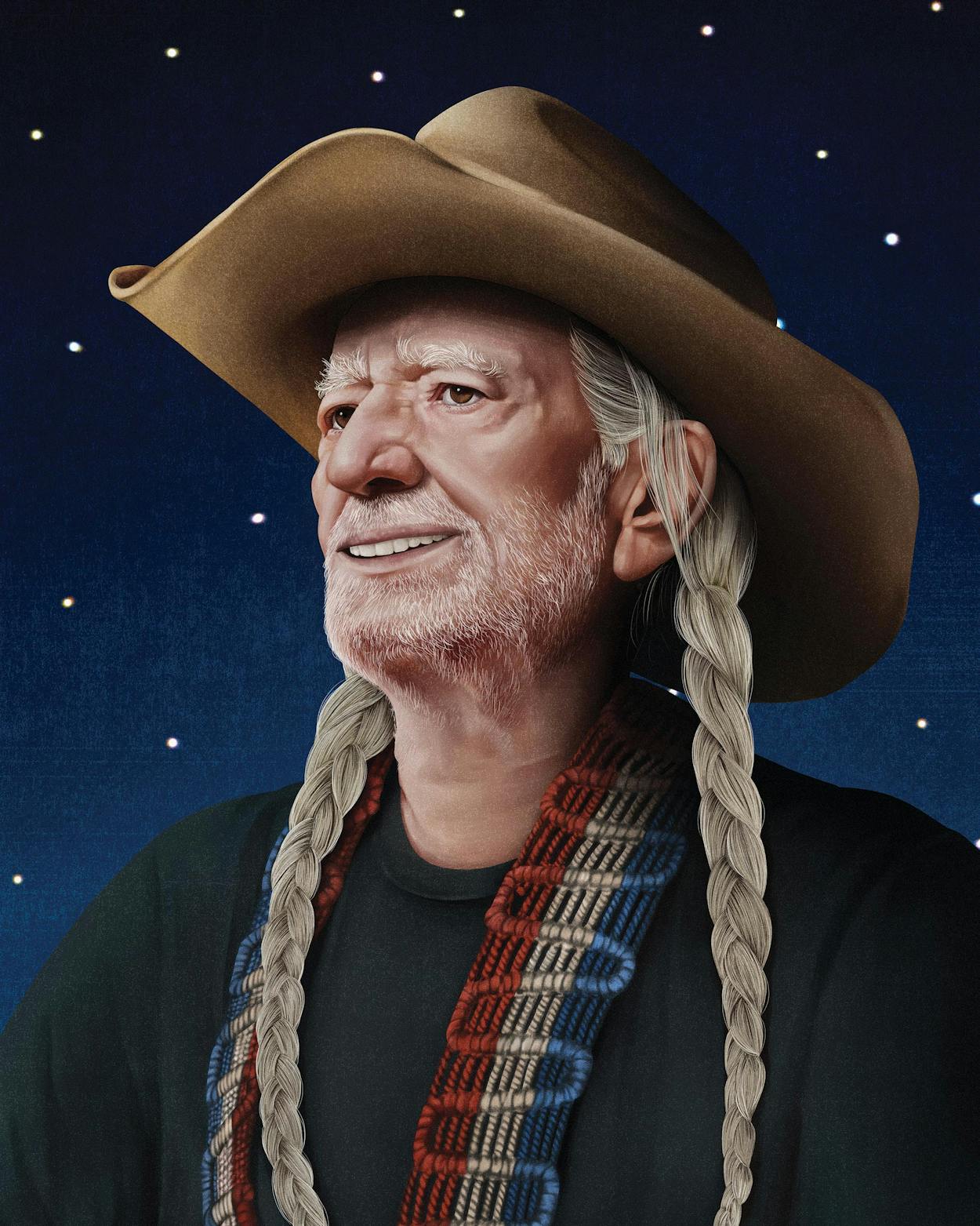

No one could have anticipated this facet of Willie’s artistry in 1960, when he drove his broken-down Buick into Nashville with songs to sell, or even after he finally found stardom with his 1975 breakthrough, Red Headed Stranger. In those distant days, country singers simply didn’t spend their time exploring old jazz songs. But then came another Willie masterpiece, Stardust, which featured not just “Georgia on My Mind,” “Don’t Get Around Much Anymore,” and “All of Me,” but also seven other songs made famous by some of the most popular vocalists of the twentieth century. Though the album seemed like a weird idea at the time, it moved Willie squarely in league with Ella, Frank Sinatra, and Bing Crosby; suddenly, a man who first made his name as a songwriter had established himself as one of the most exceptional interpreters of American popular music.

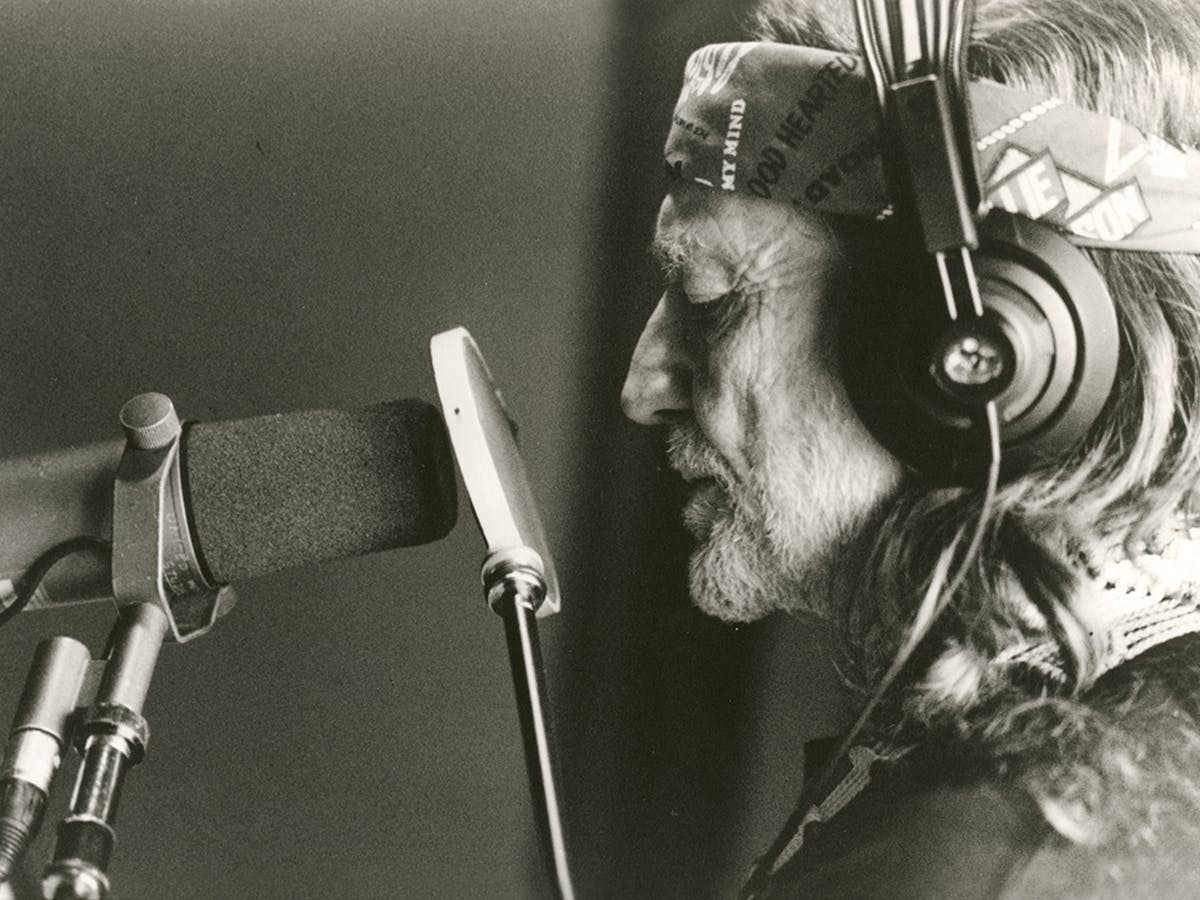

Willie celebrated his forty-fifth birthday the same month Stardust came out, and for many stars that’s a time for retrenchment and consolidation, not risk-taking and expansion. The executives at Columbia were skeptical about the album, fearing that the aging poster boy for outlaw country would embarrass himself with such a slapdash project—recorded in only ten days—made up of songs older than he was, some dating back to the twenties. Would record buyers even remember “Moonlight in Vermont” and “Someone to Watch Over Me,” let alone want to hear Willie Nelson sing them?

But Stardust turned into a megahit, rising to the top spot on the Billboard country albums chart. The lead single, “Georgia on My Mind,” became a number one country single. Then the 1926 song “Blue Skies,” delivered with a plaintive vocal twang that composer Irving Berlin never envisioned, somehow followed it to number one. And then Stardust stayed on the Billboard country albums chart for the next ten years.

It should be noted that these songs weren’t just old chestnuts picked for a theme album. These were tunes Willie had grown up with. As a child in Abbott, he heard the full spectrum of American popular song from his household’s Philco radio, which could pick up faraway stations. Night after night, he listened and learned. He heard Armstrong and Ellington out of WLS, in Chicago. He enjoyed the more countrified sounds of KWKH, in Shreveport (the station that later helped launch Elvis to fame). In 1943, when Willie was only ten, he was already admiring Sinatra, who performed on CBS Radio’s Your Hit Parade and impressed the youngster with his phrasing. In his teen years he listened to XERF, a powerhouse station operating by its own rules across the border in Mexico, that played everything from gospel to hillbilly tunes. Along the way, Willie also picked up jazz style points from a range of other performers, people like Crosby and Django Reinhardt.

Without even leaving Abbott, Willie was gaining a first-class musical education. Before the rise of commercial radio, no one in poor rural America could have been exposed to such a wide range of popular styles. But Willie took full advantage of this opportunity, picking up techniques he would put to use decades later.

Still, his greatness has come from sounding like none of his predecessors. You don’t hear the slightest hint of competition in his renditions. Willie isn’t trying to match Ella’s range or Sinatra’s breath control or Mel Tormé’s intonation. Some listeners may compare him to those role models, but Willie seems to operate in a virgin land where he’s the first person to discover these songs. In a way, that’s a more remarkable feat than any mere demonstration of vocal technique. It’s one thing to sing the old songs well, but it’s quite another to make them sound new.

Just be yourself. Countless music teachers have given students this advice, and it sounds so simple. But nothing is harder than putting an individual stamp on a song—and it’s even harder when you’re singing melodies that have already felt the imprint of the greatest singers in modern times. Yet Willie does this better than almost anyone.

Stardust is just a starting point for enjoying his exploration of the Great American Songbook. In 1983 he reunited with the album’s producer, Booker T. Jones, to record another collection of standards, Without a Song. He teamed with a small group of longtime Texas acoustic-picking buddies on 1993’s Moonlight Becomes You. Two Men With the Blues, released in 2008 and recorded with trumpeter Wynton Marsalis, and 2009’s American Classic were straight jazz efforts; 2016’s Summertime: Willie Nelson Sings Gershwin was an overdue tribute to the great composer; and 2018’s My Way was a hat tip to Sinatra, a collection of songs popularized by the vocalist who is widely regarded as America’s best.

Many formidable vocalists with huge, operatic voices and expansive ranges don’t sing with such confidence and expressive power. They may have stronger lungs but not a deeper heart.

What would Sinatra have made of all this? We can safely guess he would have been thrilled. After Stardust came out, Ol’ Blue Eyes reportedly called Willie his favorite singer. “That cat can sing,” he remarked. “That cat is a blues singer. He can sing my stuff, but I don’t know if I can sing his.” Then, in 1984, Sinatra paid perhaps the biggest tribute of all, opening for Willie at the Golden Nugget, in Las Vegas.

Occasionally, you’ll hear people dismiss Willie’s singing skills—grumbling that his range is too narrow, his style too unstudied, his delivery somehow not big enough to suit their tastes. But they underestimate Willie’s technical command as a singer. On a phrase-by-phrase basis, his performances hold up against anyone’s. Many formidable vocalists with huge, operatic voices and expansive ranges don’t sing with such confidence and expressive power. They may have stronger lungs but not a deeper heart.

Even as Willie’s vocal strength has lessened with the passing of many years, his skill with these songs has, if anything, grown. If you’ve ever wondered what a critic meant when they claimed that, in a given singer’s hands, a song sounded “lived-in,” Willie is the answer. He’s been living with songs like “Blue Skies” and “But Not for Me” for more than 75 years. Their melodies are like the house he grew up in; he doesn’t need the lights on to make his way around. He knows where the right notes go.

And then there’s the experience that comes with all those years. At some point, Willie stopped being just a singer and turned into a kind of shaman, a tribal elder who delivered not just entertainment but folkloric wisdom. To be sure, his singing now sounds weathered, and his voice is no longer able to go all the places it used to go. But therein lies the power beneath his lessons. He’s no longer just saying, “Here’s my version of this song.” Now he’s telling us, “Here is the most basic essence of this song; it’s a timeless thing that we should never forget. And I know of what I sing.”

Listening to his most recent records, you might be struck by the distance he has traveled since Stardust. In 1978 his reclamation of these old songs told us something about Youngish Willie—his drive, his daring, his to-hell-with-Nashville attitude. In 2020 his choice to keep singing them tells us something very different about Old (no -ish about it) Willie—his sense of obligation to the past and his predecessors, his sense of what remains after more ephemeral pleasures have passed. Forty-two years ago, singing these songs seemed like a mischievous act of theft. Today, it feels like an act of giving back.

Ted Gioia lives in Plano, where he writes about music, literature, and popular culture. He is the author of eleven books, most recently Music: A Subversive History.

This article originally appeared in the Willie Nelson special issue with the headline “Willie Nelson, Interpreter of the Great American Songbook.” Subscribe today.

- More About:

- Music

- Willie Nelson