Most Willie Nelson fans know at least a little about his idyllic Hill Country world headquarters, home to his ranch, his golf course, his recording studio, and his Old West movie set, Luck, Texas. But lesser known in the lore is Willie World’s gritty urban prototype, a sprawling fourteen-acre complex Willie owned for much of the eighties in the heart of Austin’s city limits.

The property ran along South Congress Avenue near the now-famous Continental Club, barely a half mile south of what was then called Town Lake, stretching east from the intersection at Academy Drive. He’d bought it on the cheap, in 1977, when the strip was a no-man’s-land, light-years away from the tony tourist spot it is now; back then its main commerce was gun shops and streetwalkers. It was the perfect place for an outlaw to build an empire.

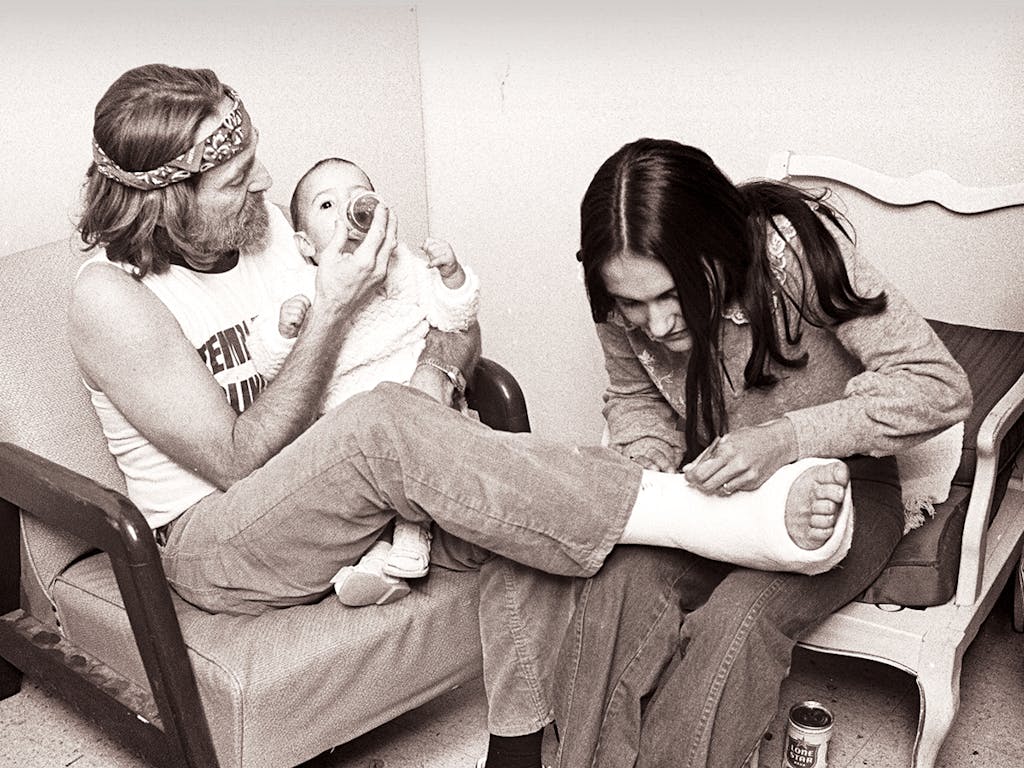

The anchor of the property was the Austin Opry House, a 1,700-seat hall run by the complex’s co-owner, Tim O’Connor. A onetime Willie capo who was bumped up to sweat-equity partner when Willie acquired the vast parcel of land, O’Connor was a music promoter from the old school, a gun-carrying hard case who turned the Opry House into Austin’s best eighties-era concert venue, a foundation for the Live Music Capital of the World moniker that the city would adopt in the nineties. The property also featured some empty South Congress storefronts, a roomy bar and grill favored by bikers and stray-dog guitar pickers, and, perhaps weirdly, some 230 flophouse apartments known unofficially as the Willie Arms. Many of the units were in two-story limestone-and-shingle structures that actually looked like apartment buildings, others were in dingy red-roofed bungalows ringed by live oaks, and all were occupied by exactly the kind of people you’d expect. Willie’s road crew—men with names like Poodie and Snake—had places to crash when Willie left the road. The Opry House staff got gratis abodes. Broke musicians dug the $65-a-month rent. Everyone there was a hippie, a misfit, or both, and none were afraid of a little dope. Some made their living off it.

Willie based his own business there, keeping an office for a record label he’d just started and opening a recording studio. And half a block down a dirt alleyway just east of South Congress, he maintained an informal rehearsal space for local musicians to work out new songs, audition new players, and just generally do their thing. As with the rest of the complex, Willie never did much to fix the building up; he didn’t even soundproof the rooms. But then he didn’t have to; the Willie mystique went a long way.

When he cashed out in late 1988—selling his interest to the same developer who is now nearing completion on a $55 million multiuse project on South Congress called Music Lane—O’Connor stayed on as part-owner and moved quickly to upgrade the rehearsal space. For years it had operated like the apartments, which were managed in a famously ad-hoc manner; somebody would show up with a note that read, “Tim, these guys are great musicians, they’re going to be fantastic. Please give them a place to stay for a while—Willie.” But O’Connor wanted the rehearsal rooms to start making money, so he brought in local music veteran Wayne Nagel to build out the newly minted Austin Rehearsal Complex and run it like a real business.

Nagel soon realized there were multiple facets to that Willie mystique—and that some could create headaches. One of his first moves was to pave the dirt parking lot on the alleyway. Within days he learned his spruce-up wasn’t universally appreciated. “We started hearing that one of Willie’s guys had buried $50,000 out there,” recalled Nagel, “and we’d just cut off access to it. The parking lot [soon developed] a sinkhole, which I figured was because somebody had come looking for that money.”

The complex was born the terrace Motor Lodge in 1951, the brainchild of a developer named L. L. “Dude” McCandless. According to old hippies who once made homes at the Willie Arms, McCandless had enlisted German bunker builders from World War II to construct the original 102 units on six hilly acres south of Academy Drive. Through the rest of the decade he grew the Terrace north toward town, and by the early sixties, Terrace ads claimed that it was Texas’s largest motor court, with 366 rooms, two swimming pools, two restaurants, and a large, air-conditioned convention center. But when Interstate 35 opened, in 1962, South Congress ceased to be a major route into town. By the early seventies, the whole area was going to seed, the Terrace included.

Willie would have first encountered the motel in the sixties, when his older sister, Bobbie, played lounge piano in its ritzy Summer House restaurant. But it first came to matter to him in 1974, after he had a falling-out with Armadillo World Headquarters owner Eddie Wilson. The ’Dillo, Austin’s first great concert venue, was regarded as the birthplace of progressive country, and the synergy between it and Willie brought national attention to both. But the marriage was short-lived. Willie has said the rift was over money; Wilson paid artists only door receipts, and Willie wanted a cut of the bar. Since the ’Dillo sold more Lone Star beer than any other venue but the Astrodome, that makes perfect sense. For his part, Wilson has always said his beef was that Willie’s guys brought guns into his club. That makes sense too.

Whatever the case, in early 1974 four music promoters leased the Terrace convention center from McCandless and christened it the Texas Opry House. Situated just three-quarters of a mile from the Armadillo and roughly the same size, it immediately posed strong competition. In its first three months, the Opry House presented Ike and Tina Turner and the Eagles, as well as local heroes like Doug Sahm and Jerry Jeff Walker. But the real coup was a handshake deal with Willie to make the Opry his go-to venue for big Austin shows, as well as those by his friends. That September, Waylon Jennings recorded Waylon Live there, an outlaw-country touchstone and one of the finest live albums ever produced.

But that iteration of the Opry House was not destined to last. The families who lived in the well-heeled surrounding neighborhood, Travis Heights, quickly wearied of post-show drunks throwing up in their yards. The homeowners’ protests, plus the venue’s reputation as a ready spot for backstage cocaine, led to trouble keeping a liquor license, which in turn led to trouble paying rent. By early 1975, the Texas Opry House had closed.

The space sat dormant for more than two years, just as Willie’s career was exploding. In 1975 he released his breakthrough album, Red Headed Stranger, his first country number one and his first to make the pop charts. In 1976 he appeared with Waylon on Wanted! The Outlaws, the first country album to sell a million copies. He was now one of country music’s biggest stars, but he still lacked a home base in Austin.

In May 1977 he struck a deal with McCandless, and the terms were pure Willie. Somehow, McCandless had won an unsecured $1 million loan from a Missouri banker in a poker game but was having difficulty making payments. Willie agreed to assume the loan, plus pay McCandless $10,000 in cash. In return he took ownership of the entire Terrace complex.

To run the new enterprise, Willie brought in O’Connor, who’d spent the previous year in Santa Fe after an unfortunate incident at an Austin nightclub had left a bullet in the leg of an A&R man from Columbia Records, Willie’s label. (Notably, when O’Connor, the shooter, apologized to Willie for any damage to his relationship with label brass, Willie responded, “Tim, I think I’m gonna let you negotiate all my contracts with Columbia.”) Willie gave O’Connor thirty days to open the renamed Austin Opry House, turn the motel check-in desk into the Backstage Restaurant & Bar, and complete the transformation of the apartments—about half of which had already been converted to efficiencies—into cheap apartments.

The Opry House promised a party that might not end, on a massive campus that the cops didn't seem to know about.

O’Connor would prove an unorthodox property manager. He staffed the Opry House cleaning crew with students from the nearby Texas School for the Deaf, partly to provide them with a decent opportunity and partly because he didn’t want anyone overhearing conversations he didn’t want overheard. He gave a warm welcome to the Bandidos biker gang members who became regulars at the Backstage but asked them to park their bikes in the ample lot behind the building, rather than on South Congress, so as not to scare off other customers. Since no one at the complex—neither the bar patrons nor the tenants and certainly not management—was interested in even a light police presence, O’Connor instructed the apartments’ security guards (read: Opry House bouncers) to deal firmly with parking lot altercations and domestic disputes in the units. And no tenant was ever legally evicted. If somebody missed too many rent payments, O’Connor would simply remove their apartment’s front door. “You’d be amazed,” said O’Connor, “how fast, almost miraculously, people who hadn’t worked in months would find jobs.”

In part to keep the peace—but also because many units were in disrepair—he limited new leases to friends and friends of friends, like-minded souls happy just to be invited to the party. A motley assortment coalesced, composed of free-living music critics, dope dealers, strippers, at least one rodeo clown, and, of course, loads of musicians. Likely suspects moved in, like Sahm, singer-songwriters B. W. Stevenson and Lucinda Williams, and members of Asleep at the Wheel. But as word spread and the music scene grew out of its cosmic cowboy phase, in came members of Stevie Ray Vaughan’s Double Trouble, power-pop band the Explosives (who backed Roky Erickson during his late-seventies renaissance), and Austin punk pioneers the Skunks.

Most of the local musicians lived in the original Terrace units south of Academy, an area so sketchy that O’Connor’s staff called it Chiapas. But the closer you got to the Opry, the more signs you saw of Willie. Most of his band members had families and homes elsewhere in town, but his crew kept apartments by the concert hall. Willie had a unit he was seldom in, preferring to stay on his bus, but he officed out of the old Summer House restaurant and was regularly seen ducking in and out for jogs through the neighborhood. Just outside the Summer House was a horseshoe of bungalows centered around a swimming pool where Willie’s right-hand man, Poodie Locke, stayed, as did O’Connor and his second in command, Roger “One Knite” Collins, notable for his master-of-ceremonies role at semiregular three-day hippie pool parties. Willie even lent one of those units to the Texas office of the National Organization for the Reform of Marijuana Laws.

But the centerpiece was the Opry House. Unlike the Armadillo, which was essentially a glorified shed where sweaty longhairs sat cross-legged on the floor to drink beer, smoke pot, and listen to music, the Opry had air-conditioning, mixed drinks, and cushy theater seats that rose up from a dance floor. It also had a world-class talent booker in O’Connor and the power of Willie’s name. “I could literally call anybody,” recalled O’Connor, “and all I had to say was ‘I’m Tim with the Opry House.’ They always said yes.” That first year alone saw shows by Muddy Waters, Tom Waits, Lou Reed, George Jones, J. J. Cale, Stevie Ray Vaughan, Bonnie Raitt, Warren Zevon, and Patti Smith, as well as the start of an annual Thanksgiving residency by Taj Mahal billed as “Turkey and Taj.”

And, of course, there were regular appearances by Willie, Waylon, and everyone they knew, which was the magic that Willie dropped on everything he touched. If he was in town, just about anybody was liable to turn up onstage or at the after-party. It might be movie and TV stars like John Travolta and James Garner, or future Texas governor Ann Richards, or bad-boy Houston Oilers like Kenny Stabler and Dave Casper. One night, Woody Guthrie acolyte Ramblin’ Jack Elliott was scheduled to perform but got too drunk to go on. No worries. Hollywood western star Slim Pickens was at the show with Willie that night—of course he was—so he grabbed a guitar, took the stage, and played an X-rated version of the old cowboy ballad “The Strawberry Roan.” Nobody asked for their money back.

The milieu was irresistible, a major part of Austin’s growing stature as one of the world’s great music cities. Through the eighties, touring acts out on the road couldn’t wait to play there. For shows in most other towns, they’d pull up to a concert hall, load in, perform, and load out. But the Opry House promised a party that might not end, on a massive campus that the cops didn’t seem to know about. And even if the artists couldn’t remember everything that had happened after the gig, they remembered they’d been to Austin, to Willie’s place.

Still, as is the case with most music venues, money was always tight. The friction with the neighborhood never did die down, nor did the notoriety for drug use. (One Knite described a George Jones show that started an hour and a half late: “Jones said he wouldn’t leave the dressing room until all the cocaine was gone. And I had a lot of coke.”) It was a pace that couldn’t be maintained; eventually the party really did have to shut down. By the end of 1988, One Knite had gotten sober and moved on, O’Connor had sobered up too, and Willie had sold his share in the property and relocated to the country. The ragged glory years were over.

These days, most old Austinites who were around back then can remember great Opry House shows, though few sensed anything of the weird world they were visiting. But if you find someone who was in the middle of it, they’ve got some stories to tell.

Nagel, who helped O’Connor launch the Austin Rehearsal Complex when Willie moved out, recalls that around 1993, when O’Connor finally sold his interest in the property, city inspectors poking around in a cluttered storeroom found several oil drums filled with bricks of Mexican weed. “We hadn’t seen Mexican weed on the streets in a while,” Nagel said. “I wondered if somebody had forgot about it. That stuff could have been in there for a decade.”

I asked O’Connor about the discovery. “That’s a true story,” he said. Had it been forgotten or misplaced? “No,” he said, almost grinning. But when I inquired about the weed with the Opry House’s longtime head of maintenance, another unrepentant old hippie named James Wright, he said no way was it Willie’s. “He always had good Hawaiian shit.”

A different version of this article was published by Wildsam Field Guides in a booklet created for Austin’s Hotel Saint Cecilia in 2018.

More Essays About the Red Headed Stranger:

Willie Nelson, the People’s Champion

Willie Nelson, Interpreter of the Great American Songbook

- More About:

- Music

- Willie Nelson