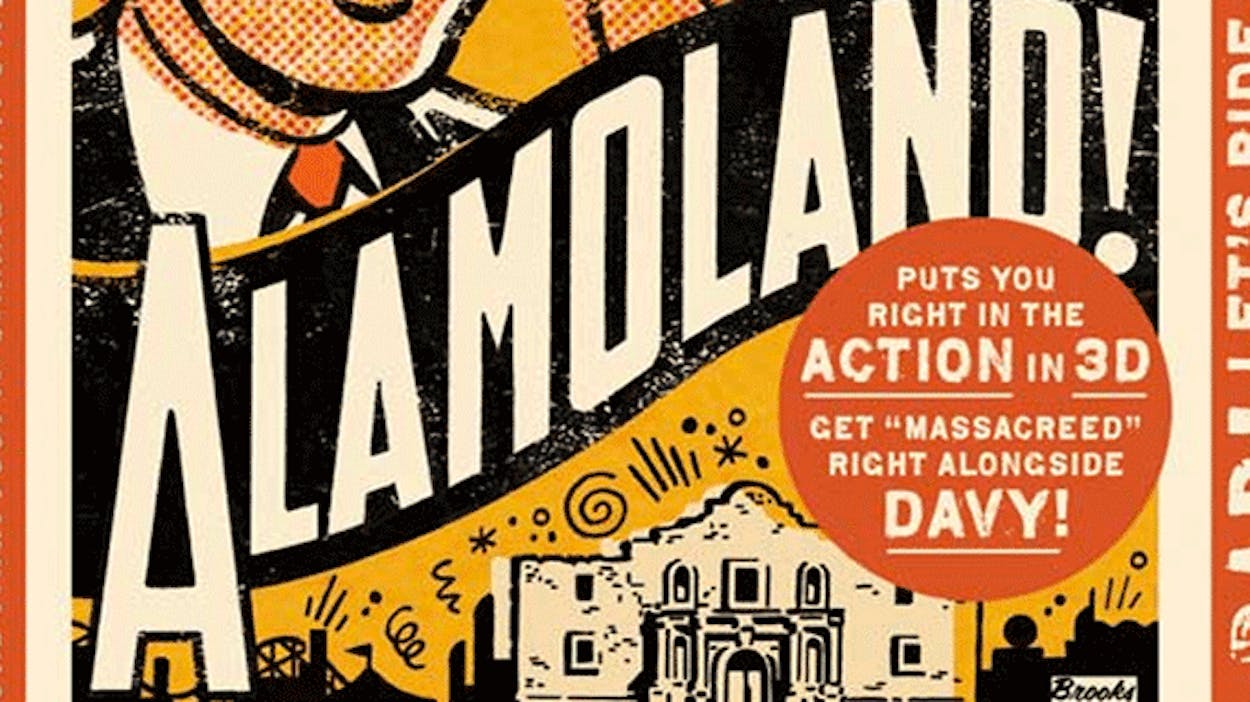

Across the street from the Alamo, on the very spot where Lieutenant Colonel William Barret Travis established his headquarters and wrote his famous letter pledging to fight until “victory or death,” the scratchy voice of an actor in a top hat, wig, and blood-spattered tuxedo shirt beckons tourists into Ripley’s Haunted Adventure. His name is Stumpy. A shabby sidewall of Ripley’s Believe It or Not faces what was once the southwest corner of the old fortress, where Alamo defenders positioned their largest piece of artillery, an eighteen-pounder. This was probably the cannon that Travis fired in reply to Santa Anna’s demand for surrender. The City of San Antonio erected a small plaque here a few years ago, but hardly anyone notices it amid all the commercial junk. In the early 1900’s San Antonio’s famed British-born architect Alfred Giles turned the Alamo’s west wall into a handsome row of buildings, but over the years the ground floors have been taken over by a sad assortment of tawdry curiosities, such as the Tomb Rider 3D ride and arcade and the Guinness World Records Museum. A little farther down Alamo Street are the Louis Tussaud’s Plaza Wax Museum and the Ultimate Mirror Maze Challenge. Three million people visit the Alamo every year, and hundreds of thousands of them must pass along this sidewalk without realizing its historical significance or recognizing that this portion of the most iconic location in Texas has been allowed to go to seed.

In July I visited the Alamo in the company of Gary Foreman, a filmmaker and historical preservation specialist who splits his time between Chicago and San Antonio. For more than a quarter of a century, Foreman has been protesting the degradation of this site, trying to get someone to listen. Occasionally, someone does. Back in 1984, when Greg Curtis was editor of this magazine, Foreman enticed him to tour the Alamo too. Dismayed by the negligence and the lack of respect for the history that he found in abundance, Curtis concluded that “little effort is made to explain what the Alamo was and what happened there.”

Though things have improved somewhat since then, Foreman remains disgusted by the level of neglect in Alamo Plaza. “Texas invests very little in its historic assets,” he told me. “Not only are we not protecting our heritage, we are losing billions in tourist revenue. People come here looking for the American West, not Ripley’s.” Foreman, who is 58 years old, became obsessed with the Alamo as a Wisconsin schoolboy in the fifties, watching Fess Parker in Disney’s Davy Crockett miniseries. “My generation learned American history from television,” he says. “For some reason, the Alamo resonated with me.” Foreman moved to San Antonio in 1984 and since then has remained a part-time resident. Last spring, he and a group of historians armed themselves with old maps, research materials, tape measures, and a permit from the city and retraced the original boundaries of the Alamo compound, redefining (and in some cases correcting) history.

Their project was long overdue. Visitors seldom fail to remark that the Alamo is so much smaller than they imagined, but that’s because they are looking only at the church and the long barrack, where Davy Crockett and a handful of defenders made their last stand. Most of the fighting actually took place at the now nonexistent walls surrounding Alamo Plaza and within the plaza itself, which stretches as far west as the wax museum and as far north as the U.S. post office. The post office covers the site of the old north wall, the traces of which are outlined in stone along the crosswalk on Houston Street. As waves of Santa Anna’s troops stormed the Alamo in the early-morning hours of March 6, 1836—they came from the direction of what is now the parking lot of the Scottish Rite Cathedral—they were slaughtered in great numbers by a battery of eight-pound cannons fired through embrasures in the top of the north wall. After two failed attempts, they finally breached the wall. Travis, shot through the head, fell about twenty feet from the post office’s southwest corner, near what is now a stairwell leading to a nondescript side entrance.

This was the crucial turning point. Once inside the walls, the Mexican soldiers killed the gun crews before they could spike the barrels of their cannons, then wheeled the intact battery to the area of Alamo Plaza now occupied by a cenotaph—a giant stone monument to the fallen defenders—and blasted off the doors of the church and the long barrack. The breach of the north wall was the beginning of the end—or more accurately, the end of the beginning—of the Republic of Texas. Yet the only clue that anything important took place here are two tiny bronze indicators on the sidewalks on either side of the post office, noting “Alamo Mission original property line.”

Another bronze marker, on the opposite side of the plaza, at the old south gate, denotes the site of the low barrack, where Jim Bowie, sick and no longer able to defend himself, was killed. The Texas Historical Commission erected the plaque in 1996, after archeologists discovered the foundation of the low barrack. The south gate was guarded by an earth-and-log redoubt, manned by an unknown number of Texans and two artillery pieces. Crockett and his “Tennessee boys” defended a low barrier called the palisade, connecting the south wall and the church. As was the case along the north wall, the carnage at the south gate was horrendous. Those who survived the attack on the walls retreated to the long barrack and the chapel, where they were killed minutes later. In about the time it takes to play half a football game, all 189 defenders of the Alamo were dead.

Considering the abuse heaped on it through the ages, it’s a miracle the Alamo survives at all. The Catholic Church hadn’t even completed work on the church in 1793, when it decided to close the mission. The church didn’t have a roof, much less its famous bell-shaped parapet, until sixty years later, when the U.S. Army used it as a quartermaster’s depot. Following Mexico’s independence from Spain, the building’s stones were nearly sold for auction to finance the new state of Coahuila y Tejas. Shortly before the battle, Sam Houston proposed abandoning the fort in a letter to then-governor Henry Smith, a proposal Smith had the foresight to dismiss. The Alamo was about to be converted to a hotel in 1905 when Clara Driscoll rescued it with a gift of $65,000 and put the Daughters of the Republic of Texas in charge of the site. Somehow it managed to survive several pitched battles within the ranks of the DRT, the most notable being the one between Driscoll and her rival, Adina De Zavala, who barricaded herself inside the convento to protest Driscoll’s plan to demolish the building’s second floor. Another plan, fortunately aborted, would have razed the convento and replaced it with a Beaux Arts—style building.

It was not until 1968 that the long barrack was restored and opened as a museum—at least in name. There wasn’t much to see. When Greg Curtis was there, the relic that caught his eye was the coonskin cap worn by John Wayne in The Alamo. In 2005, to celebrate a century of custodianship of the property by the DRT, the barrack was renovated and upgraded into a true museum. Its artifacts now include weapons of frontier defense, a Bible that belonged to a prominent early Texas family, a ring that belonged to Travis, and reproductions of uniforms worn by the Mexican infantry and the New Orleans Greys (Wayne’s coonskin cap is no longer displayed). The panels covering the windows that face Alamo Plaza are painted with bright depictions of life in the first half of the nineteenth century. At the north end of the barrack porch is a representation of the first hospital in Texas, established at the Alamo’s Spanish garrison in 1805. Outside, between the barrack and the gift shop, is the Wall of History, placed there in 1997, presenting in detail a timeline of the mission and the village across the river, San Antonio de Béxar, and outlining the indispensable role each played in the history of Texas.

Yet inside the nave of the church, visitors will find few explanations. “People want to see the space, not signs,” Alamo historian and curator Bruce Winders told me. Even so, the DRT has always seemed more worshipful of the Alamo than respectful of its history, piously referring to the church as “the shrine.” Fighting through a mob of people, many of them pushing baby carriages, I gave up trying to get a close look at exhibits and concentrated instead on inhaling the essence of the place. People spoke in whispers, sounding more confused than enlightened but curious and aware of a palpable connection to these old walls. Some of them listened to a narration on headsets supplied by the Alamo’s audio-tour service. I crowded in behind a Latino family trying to get a glimpse of Crockett’s rifle and caught fragments of Spanish as the parents explained the story to their two young children. I wasn’t sure of their words, but it was clear from the shimmer of pride in their eyes that they regarded the Alamo as an irreplaceable part of their heritage. Whoever we Texans are as a people, it started here.

The last defenders of the Alamo, probably fewer than twelve, fought inside these church walls. Though neither of the two rooms just inside the main entrance is identified, the one on the right was the baptistery and the room across from it the confessional. Both were used as powder magazines at the time of the battle. Robert Evans, an Irishman who had joined the cause of Texas independence, was attempting to torch the magazines to keep them out of enemy hands when he was shot dead near the front door. Another of the final defenders was James Butler Bonham, who carried a message through the Mexican line asking for reinforcements, then raced back to the Alamo, knowing he would die inside. Jacob Walker, of Tennessee, ran into the sacristy to hide, but pursuing Mexican soldiers shot him and hoisted his body onto their bayonets. The sacristy, a double room on the left side of the corridor, was where the women and children took shelter during the fighting. After the battle ended, Susanna Dickinson and her infant daughter, the only Anglos in the group, were led from the sacristy and out the front door of the church, where she recognized amid the carnage the mutilated corpse of Davy Crockett. She identified Crockett because of his “peculiar cap.” Historians are not certain if Crockett died in battle or was executed, but the oral history handed down from Dickinson (who couldn’t read or write) places the spot where his body fell just outside the northwest corner of the chapel, below walls that still appear pockmarked and battle-scarred. A Mexican olive tree grows there today. As Curtis reminded us, all this drama and more happened in the chapel, but you have to go to considerable trouble to appreciate it.

The City of San Antonio owns 70 percent of the original Alamo compound (the state owns, and the DRT manages, the church and the grounds behind it). Were it so inclined, it could make substantial improvements, as it did a few years back when it renovated the Main Plaza, located next to San Fernando Cathedral. In 1994 the city closed Alamo East, one of two streets that ran through Alamo Plaza. Visitors no longer choke on the fumes from idling tour buses. The motivation for closing the street was as much political as historical, however, coming in response to protests by Native Americans that the plaza had been a burial ground for their people.

No one has yet implemented a grand vision for giving the Alamo a comprehensive perspective, connecting the historical dots, as it were. Foreman represents a group of business, professional, and educational leaders who are working on a plan, but he’s not ready to reveal who they are or what it is. My guess is that Foreman’s scheme will be too grandiose to be practical. He and his people will have to persuade the federal government to repurpose the post office, and restoring the west wall would require demolishing the work of Alfred Giles. “The quandary is,” Winders says, “do you destroy something historic to put up something nonhistoric?”

Unfortunately, this question went unasked for many years. Yet as I crossed the sacred ground, weaving my way through snow cone stands and listening to the grating voice of Stumpy and the other wonders in the phony world of Ripley’s, I realized that we shouldn’t aspire to have the Alamo restored all the way back to 1836, to the ruins of a roofless, dirt-floor church. For one thing, we’d miss the world-famous bell-shaped parapet. Short of total restoration, however, there is plenty of room for improvement. The city could start by closing the remaining lanes of traffic on Alamo Street. It is not too late to remember the Alamo. Believe it or not.