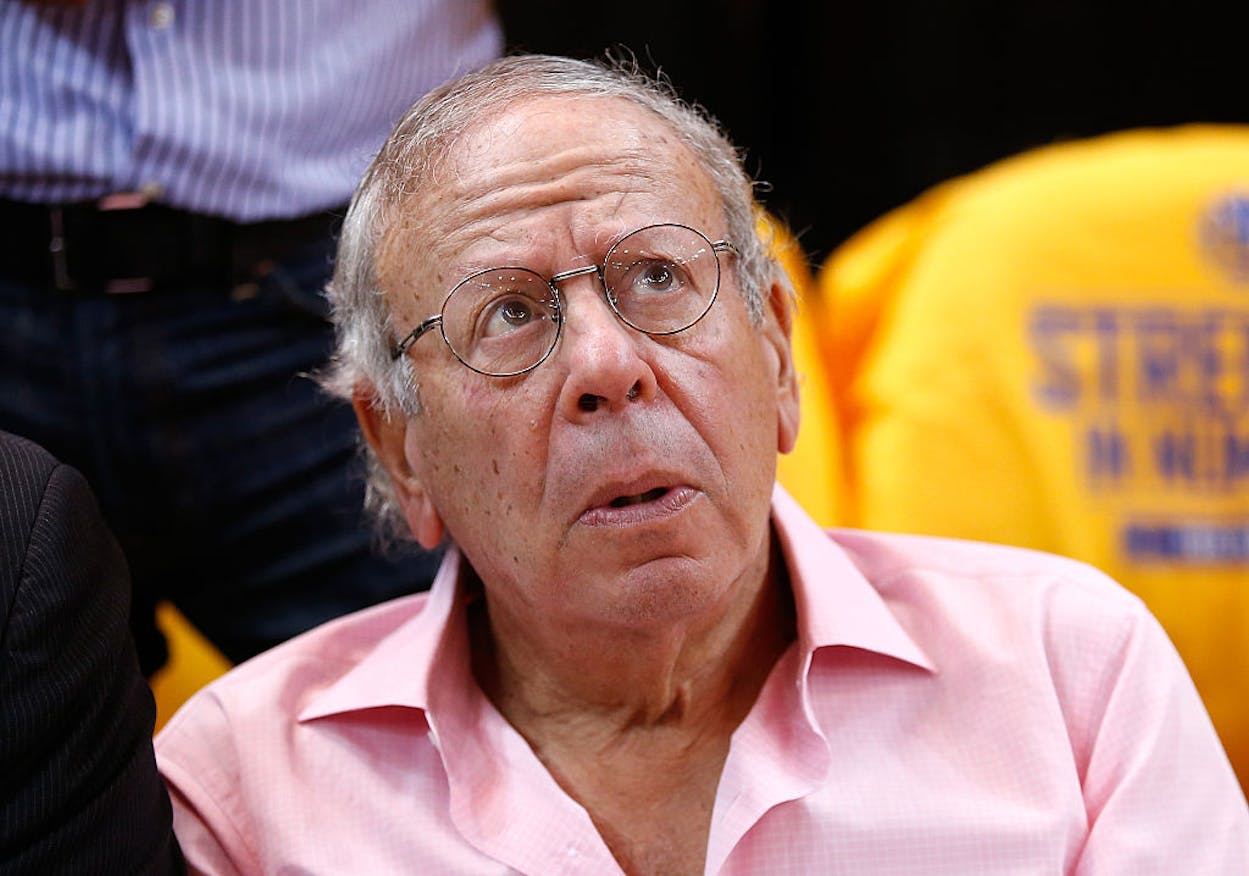

To the astonishment of sports devotees everywhere—and even most within the Houston Rockets organization—owner Leslie Alexander announced on Monday that he is selling the team.

“It’s been my great joy and honor to own the Rockets for the past 24 years,” he said in a press release. “I’ve had the incredible opportunity to witness true greatness through the players and coaches who have won championships for the city, been named to All-Star and All-NBA teams, enshrined in the Basketball Hall of Fame, and done so much for our franchise and our fans. And the Houston community has been home to me . . . I’ll always have a special place in my heart for the fans, partners, city officials and employees who care so deeply for this team.”

Alexander stressed that he would not rush the sale—that he would find the perfect fit for a franchise he must regard as his baby. (And chill on the Rockets-to-Seattle or Vegas talk: whoever the buyer is won’t be moving the team unless they want to buy out a Toyota Center lease that does not expire until 2033.)

Unlike any other Houston professional sports owner, save for the rising but as-yet unproven Astros honcho Jim Crane, it’s hard to find fault with Les Alexander’s tenure in the Rockets’ cockpit. Admittedly, Houston’s bar is low. Bob McNair’s Texans are the only team in the NFL never to have reached a conference championship game, and Bud Adams’ Oilers ripped our hearts out time and time again before decamping for Tennessee. The Astros are the oldest baseball franchise to have never won a single World Series game, and Crane’s predecessor Drayton McLane fiddled for years while the franchise burned, leaving Crane no choice but to bulldoze the ruins of a once-proud franchise. (Well, as proud as any team can be with one measly pennant, anyway.)

Simply put, over the course of 145 completed “Big 4” (NBA, NFL, MLB, and the inapplicable NHL) pro-sports seasons in the Bayou City, Alexander’s Rockets have hoisted the only two titles. Plus, his Houston Comets WNBA team, with their record setting four-peat, gave Houston its only true dynasty.

Yes, you could say that Alexander lucked into the city’s first championship, which was clenched in his first year of ownership. Arguably, no rookie owner in any sport ever had it so good. That 1993 to 1994 team roared out of the gates with a league record—tying fifteen straight wins—but it was almost entirely built under the regime of his predecessor, Charlie Thomas. Alexander inherited a nucleus of a rededicated Hakeem Olajuwon (whose newfound embrace of his Muslim faith saw him curtail his nocturnal shenanigans), Otis Thorpe, Vernon “Mad Max” Maxwell, Kenny Smith, Robert Horry, Mario Elie, and coach Rudy Tomjanovich.

Rookie Sam Cassell, a steal drafted near the end of the first round, was the only significant player to that team brought in under Alexander’s watch, and if at first his contributions were fairly insignificant, Cassell took off at the end of the year, continuing his rise in the playoffs. When Olajuwon and company finally took down the New York Knicks in a bruising seven-game series pandemonium erupted on the city’s Richmond Strip, then the city’s unofficially designated party zone. The Bayou City’s long municipal sports nightmare was over, even if few outside of New York and Houston turned off O.J. Simpson’s Bronco chase long enough to watch.

“It was kinda surreal,” says John Egan, son of former Rockets head coach Johnny Egan and a one-time ball boy for the team. “You are so used to getting the rug pulled out from under you as a Houston sports fan. We’d come close a couple times before, so you were always waiting for the other shoe to drop but it didn’t happen that year. Somehow you know they were going to do it because of how they how they’d played all year.”

Alexander deserves more credit for the repeat the following season. Just as Smith was starting to falter and Mad Max’s explosive temper and off-court antics become too much to bear, Cassell continued to blossom, but that paled in comparison to the midseason trade that sent popular power forward Thorpe to Portland for hometown hero Clyde Drexler.

Hoops illuminati panned the deal at the time.

“We got a lot of bad press on the Clyde trade,” Alexander said at the team’s twenty-year reunion two years ago. “Everyone was saying, ‘How can you trade a starting power forward for a 6’6 guard?’, but he was one of the top 50 players of all time. I just thought it would be unbelievable for us, and it proved out that it was.”

And for a time, it looked like the naysayers were right. Those who applauded the return of the Sterling High School product and Olajuwon’s UH’s Phi Slamma Jamma frat bro were thinking with their hearts and not their heads, it seemed, as the Rockets limped to season’s end with a 17-18 record after the swap. They reeled into the playoffs as a sixth-seed, a behind-the-eight ball position from which no NBA team had been able to emerge victorious.

Until the Rockets miraculously pulled it off. Although it was the otherworldly playing of Olajuwon that carried the team to come-from-behind series wins (and a 5-0 record in elimination games), a hard-fought seven-game victory over NBA MVP David Robinson’s San Antonio Spurs, and the championship sweep over Shaq’s Orlando Magic, the Dream was not Houston’s only hero. “Big Shot Bob” Horry, “Kiss of Death” Elie, Drexler, Smith, Cassell, and even lowly Chucky Brown all stepped up at key moments.

In the minds of locals, Houston had become “Clutch City,” a proud moniker superseding the “Choke City” nickname bestowed upon us after many an ignominious collapse courtesy of the Astros and Oilers. Les Alexander had done the impossible—his team had made this city of cynical, perpetual losers believe, if just for a couple of years, that there were such things as fairytale endings. What’s more, he’d done with people Houstonians had known, loved, and suffered with for a decade or more. There was beloved, hard-partying, hoarse-voiced coach Rudy T, whose career we’d all seen curtailed by that devastating Kermit Washington on-court haymaker. Many of us had wept along with Clyde the Glide and the Dream on that horrible night in 1983, when Lorenzo Charles’s buzzer-beating dunk for NC State went in the NCAA Tournament books as one of the biggest upsets since Naismith first screwed up a hoop.

And then, years later, there were the three of them together, showered with confetti, hoisting that golden basketball, weeping tears of joy this time. “How sweet it is!” acerbic Rockets announcer Gene Peterson exulted. After years of all-star play for good but not great Portland teams, Drexler finally got his ring, alongside Olajuwon, redeeming their shared UH tragedy. And in that harsh Detroit accent of his, a disheveled Rudy T took note of all the times his team had been written off as doomed. “Don’t ever underestimate the heart of a champion,” he advised.

Like the old song says, those were the days, my friend, we thought they’d never end, but end they did, and abruptly so. Maybe it was the abandonment of the mustard-yellow and fire engine red uniforms after the second title, or maybe the move to plush Toyota Center (which doubled the franchise’s value, if not its success), but the Rockets have been snakebit ever since.

Twenty-two seasons have come and gone since those joyous nights in the Summit, and in that span, the Rockets have won only six playoff series and have reached the Western Conference finals only twice, almost twenty years apart (and were subsequently bounced with extreme prejudice both times).

But here’s the thing. Through all those years of frustration, Alexander’s teams have almost always been competitive and exciting, and they almost always featured at least one elite player, a star attraction. Under his ownership, Rockets fans have endured only three losing seasons in a very tough Western Conference, and since Alexander hired whiz kid GM Daryl Morey in 2007, none at all. Over the course of Alexander’s ownership, in addition to those two championships, the team has posted the fifth-best winning percentage in the league.

Unlike a few NBA teams in recent years, the Rockets have not had to tank a season or three to set up a better future, and with this year’s offseason additions like future Hall of Fame point guard Chris Paul and elite perimeter defender Luc Mbah a Moute (and possibly scoring machine Carmelo Anthony), whoever buys this Rockets team will inherit a squad with as much of a shot at a first-year championship as Alexander enjoyed in 1993, Lebron and his Cavs and the Warriors be damned.

But who will get the chance to see that through? Speculation ranges from unnamed Chinese billionaires (thanks to Yao, Jeremy Lin, and current Rocket Zhou Qi, the Rockets are China’s team), to local restaurant tycoon Tilman Fertitta, who is sports-crazy, rich, and would greatly enjoy becoming even more like the Mark Cuban of Houston.

Think about it: Fertitta could fill the concourses at a renamed Landry’s Arena with Bubba Gump, Saltgrass Steakhouse, and Landry’s outlets, while the fatcats on the club level could feast on Willie G’s and Vic and Anthony’s steaks. High-rollers from his Golden Nugget casino in Lake Charles could be flown in to games with comped tickets.

As for Alexander, don’t cry for him. He bought the team for $85 million in 1993, and is expected to sell the team for somewhere between $1.6 and $2 billion. Or maybe more. If sports wonk Bill Simmons is to be believed, the H-town squad could go for a half-billion or even a billion over that estimate.

That’s a big chunk of change for Alexander. Houston writer Cort McMurray pointed out that if you bought a Toyota Corolla—the car, not the center—for $18,500 and sold it at the same profit margin (1547 percent) that Corolla would fetch close to $27 million—and that’s using the low estimate of what the Rockets could fetch.

Which is enough to make haters of many of us. But sports is irrational, and for those of us who can remember it, what Alexander brought the city of Houston—whether he attained it by simply not messing up a good thing or not—was priceless.

I’ve always believed that sports teams are in the unique position to make a real difference in their communities,” Alexander once said. “When I bought the Rockets, that was my dream. I hoped to make a difference for the people of Houston, both emotionally and financially.”

OK, the financial difference in Houston—save for Alexander and his players—seems aspirational. But he sure made a difference emotionally, for two short years, two decades ago. And we are still riding off of those fumes today.