Fain’s unsuccessful queso field trip, along with similarly futile searches for good restaurant refried beans and other Tex-Mex staples, prompted her to take matters into her own hands—and kitchen. The Homesick Texan was born. Fain’s efforts to make her own versions of the food she craved from home turned into an acclaimed blog, and then a pair of cookbooks: The Homesick Texan Cookbook (2011), and The Homesick Texan’s Family Table (2014). Texpats around the country and the world, this writer included, have had their lonely palates soothed by Fain’s recipes for classics such as homemade flour tortillas, cheese enchiladas, and chicken-fried steak.

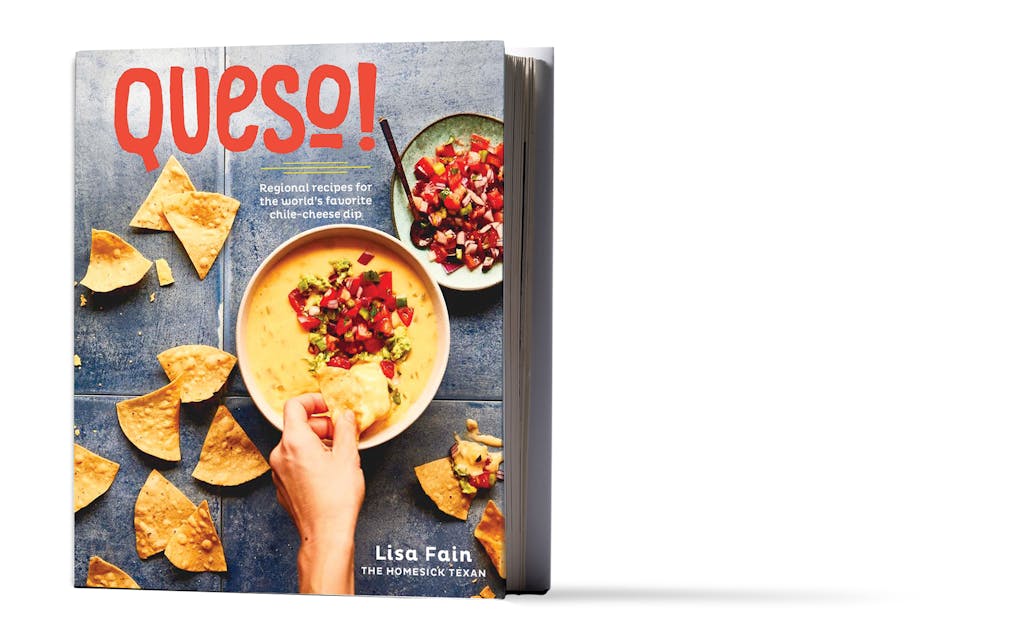

Ro-Tel has been a lot easier to find in New York after it was purchased by ConAgra Foods in June 2000. That means the world is finally ready for Fain’s third cookbook, Queso! (Ten Speed Press). It’s a single-subject tome that still contains multitudes, whether you are a Velveeta-lover or an Asadero evangelist. Fain, er, dips into queso’s history around Texas and the border, while delivering her own versions of quesos inspired by such restaurants as Houston’s Felix, Austin’s Kerbey Lane Cafe, and Fort Worth’s La Familia. There are also regional specialties (Laredo’s choriqueso, El Paso’s huevos rancheros), unexpected old-time versions (queso on toast?), and modernist inventions (Indian chutney queso, vegan queso).

Texas Monthly spoke to Fain by phone from NYC about such topics as anti-Tex-Mex snobbery, the fake Arkansas cheese dip wars, and Lubbock’s surprising role in queso history. Plus, she shares two of her recipes from the book.

Jason Cohen: Do you have kind of a “Rosebud” memory of your first chile con queso?

Lisa Fain: You know, you’re not the first one to ask me that, and I don’t, unfortunately. I’m kind of more Proustian about refried beans than I am about queso, but I’ve always loved it. It was just one of those things that was always around—at every gathering, at church youth groups, and for every football game watching. So when I moved to New York, it was like, “What, the rest of the world doesn’t eat queso?!” That to me was kind of the beginning of this journey.

Yeah, there’s tacos everywhere, and there’s some kind of regional Mexican food in most places. But Tex-Mex, and queso specifically, are more elusive.

Most of the places that are heralded for their Tex-Mex are owned by former Texans, like Ford Fry in Atlanta, or Home State in Los Angeles, and even Javelina here in New York. But it’s not something that has crossed over. It’s still very much Texans evangelizing for it.

JC: And there’s still that peripheral snobbery, which you allude to, not just against Velveeta, but against Tex-Mex overall.

LF: Yeah, I think Diana Kennedy was the one who started it way back when when she was like, “This is not Mexican food.” And it’s not Mexican food. It’s American food. It’s Texan food. It takes from many cultures and it’s its own thing. Once you embrace that, and realize how delicious it is, you can be fine with it. I think people got confused because for many, many, many years it was touted as “Mexican food” in Texas. Even I, growing up, didn’t know any better, so I assumed it was what they ate in Mexico.

JC: Just like American hot dogs aren’t exactly the same as German sausage.

LF: Exactly. You can see this with many cultures. American Chinese food, or American Italian food. It’s what immigrants have always done with what’s available: create an American cuisine based on their homeland. As long as you don’t think it’s going to be authentic to what you would get in the mother place, you’re fine.

JC: A theme throughout the book is that queso is as much about sharing it with other people as it is about the food itself. So are your queso memories more home-based than restaurant-based?

LF: They’re pretty much equal. There was the ubiquitous crockpot, where everyone would be hanging out dipping their chips into the queso. But there wasn’t much experimentation in home-style queso. It was pretty much standard Velveeta and Ro-Tel. Sometimes people would throw in breakfast sausage, or maybe there’d be guacamole.

But it was more the restaurants that showed me queso can be more than just canned tomatoes and green chiles with processed cheese. It was things like Bob Armstrong Dip, where they had picadillo; it was a different flavor and they didn’t make it with Velveeta, so the cheese tasted a little bit more refined and more creamy. The chile con queso they serve at restaurants in El Paso, I’d never seen that in a home situation. Or even things like queso fundido and queso flameado. When I was trying to delineate what I was going to put in the book, I decided, if there are chiles and there are cheese, than it’s chile con queso.

JC: Right, fundido and flameado are not really Tex-Mex right? I can go to Chicago and find that a lot more easily than I could chile con queso.

LF: I had a really hard time getting the history of that. I spent a long time in San Antonio reading old Mexican cookbooks from the 1800s and there was no mention of queso fundido or queso flameado. The earliest mention I found was the 1940s or 1950s. Chile con queso, the phrase, appeared in print in Mexican literature way before queso fundido.

JC: One thing I had never really thought about was the connection between queso and Welsh rarebit, but it makes so much sense. One of the earliest recipes you feature is for “Mexican rarebit,” still served on toast rather than tortillas.

LF: Yes. For me, a lot of the deep diving on that occurred when the people of Arkansas a few years ago started saying, “Oh, chile con queso is from here.” And I was like, “Oh, that’s ridiculous. That’s just impossible. Chile con queso obviously did not come from Arkansas.” I knew that was wrong, and I was really frustrated because everyone just kept toeing this party line.

So I wanted to have something on record that defended queso’s dignity. I knew it probably didn’t come from Texas either. I knew it probably did come from Mexico, and it did. But for me the interesting thing was, how did it turn into this processed cheese dip? How did it go from being this white cheese with tomatoes and and green chiles, that’s almost like a side dish, or a really thick topping? The first chile con queso recipes that appeared in print—either in the American press or in Mexico—that’s what it was. And it is what you still find in northern Mexico.

So when I was doing kind of the timeline, I found the recipes for “Mexican rarebit,” which was rarebit made with American cheese. Classic rarebit is cheese and liquid and maybe an egg, served over toast. Well, the Mexican rarebit, the recipes would call for American cheese, but it had green chiles and tomatoes and aromatics and I was like, “Oh my God, they found this recipe for chile con queso and they basically glommed it with rarebit.” So that for me was kind of the turning point for queso.

JC: And as you mention in the book, even the restaurant in Arkansas that claims to have invented it was owned by Texans.

LF: Yeah, the whole thing was shoddy. Don’t get me started. He and his wife had owned a place in East Texas. Kilgore. The funny thing is, the Arkansas people were like, “It was a man from the border.” And I’m like, “yeah, the Louisiana-Texas border!”

JC: One surprising thing you found is that Lubbock can take credit for the first use of Velveeta.

LF: The first one that was published anyway. I had that woman’s name, she was obviously a cook who liked to submit her recipes to community cookbooks, but I couldn’t find her relatives. You saw American cheese in all these queso recipes until that point, in 1939. That kind of dove-tailed with Velveeta becoming more widely available. One of the ways they originally sold it was as a cheese sauce, so it was kind of inevitable that would happen. But that was actually the first occurrence of it in print.

JC: You write that Lady Bird Johnson’s White House chef dismissed queso as “chile concrete.” Does that mean his emulsification technique was lacking?

LF: I think he was just being a snob, and probably turning his nose up at Velveeta. When [Johnson] submitted her recipe to the Washington Post, it didn’t call for Velveeta. It was submitted with aged cheddar. But nobody was making queso that way. I think she wanted to make it seem more sophisticated.

JC: So ultimately, you decided that the border and the El Paso area is queso’s spiritual birthplace.

LF: Yeah. I couldn’t pinpoint the exact location, but the primary chile pepper for chile con queso is the long chile—a Hatch or Anaheim that’s not that spicy—and that’s where they grow, that’s their natural habitat. And there’s an abundance of dairy there. The queso that you find in El Paso is very similar to the original incarnation of what chile con queso was described as. They serve it with tortilla chips now too, and also as a sauce or with tortillas, but they haven’t really embraced processed cheese queso. More than likely it’s going to be made with a white cheese like Asadero or muenster, one of those cheeses that melts, but that’s not processed, and is tangy and stringy. They also add liquid and aromatics and tomatoes and green chiles. I think if you want to know the beginnings of chile con queso, that’s a good place to start.

JC: I guess in way, the classic Tex-Mex chile con queso should really be called queso con chile?

LF: That’s a really good point. It started out as an abundance of chiles. They were equal partners. The original dish was actually a side dish. Like a gratin. Chile peppers with cheese. So this is what it evolved into, and it became a little bit more soupy, but there really is an emphasis on chiles. And if you cross the border into Juárez and order chile con queso you pretty much get the same thing.

JC: I was surprised at how often fresh tomatoes factored into some of these recipes in the book.

LF: Versus canned tomatoes? That’s just a flavor preference. Sometimes I called for Ro-Tel. I think that just kind of hearkens back to how my cooking style evolved, since it was just so hard to find them for so many years. I also wanted to pay respects to El Paso, even if I was doing a processed version, because they use all fresh ingredients. And I just think it tastes better.

JC: You also found a totally different version, one that happens to be one of my favorite things to eat in Texas: the huevos rancheros at the H&H Car Wash.

LF: Yeah that was an eye-opener. I had no idea. I’m at the H&H and it’s processed yellow cheese queso being poured over fried eggs and I was like, “what is that?” And they’re like, “this is huevos rancheros.” No one knew anything about the origin. But it’s a thing in El Paso.

JC: Aside from the completely non-Mexican, sort of fusiony quesos you include, like queso with chutney, what was the most surprising variation that you found?

LF: Well there was one recipe in the El Paso Junior League Cookbook, “Seasoned with Sun,” which was called Summerime Queso, I believe, and it was made with cottage cheese as the base. I was like, “that is weird,” but I figured it was in the El Paso Junior League cookbook, and it was even in their “Mexican” chapter, so I was like, “Ok, maybe it’s authentic to them.”

It’s made with cottage cheese and it has pickled jalapenos and onions and diced avocado and you eat it with tortilla chips, but you serve it cold and it’s delicious. Very refreshing on a really hot, Texas day. It hits all your pleasure centers for spicy and creamy. That was probably the biggest surprise.

JC: Did you eat a lot of vegan queso in restaurants over the years or is that something you did for this book?

LF: No, I’d had a lot of vegan queso. It was all awful. I have lots of vegan friends, or friends who can’t eat dairy for whatever reason. A few years ago there was a jarred vegan queso that came out and they were over-the-moon excited about it. So I know that I wanted to have something for them. And then I had some at this place in San Antonio, and it just tasted right. And what the trick was—for whatever reason no one else had done this—was that they used Ro-Tel. Cause Ro-Tel really has a very distinct flavor, the tomatoes and the green chiles and the spices that they use. When you taste it in a creamy base your mind instantly registers “queso.” So for both of my vegan quesos I do call for Ro-Tel. One has a nut and carrot base, and one has a vegan cheese base. I actually had these recipes tested by regular cheese eaters, and they loved them. And vegans loved it too.

JC: There’s also a recipe where you sub queso for cream gravy on chicken-fried steak. My first reaction to that was, “OK, that’s a little much.” But then I wondered, does queso actually have more fat and calories than cream gravy?

LF: I would think queso probably has more calories than cream gravy. But maybe not. Processed cheese doesn’t have as many calories as regular cheese. It is over the top. It’s total decadence. But I don’t think it’s severely more worse than eating cream gravy. If you’re a total queso fan and a total chicken-fried steak fan, I think you deserve to try it at least once. Because it works.

JC: Is there anything that queso should just never touch?

LF: Doughnuts maybe? There’s that thing at the Texas State Fair, the funnel cake burger with queso, and I think that sounds kind of gross. But it might be good, who knows? That’s part of what this queso journey was for me. There’s a whole world of experimentation. It’s a good base for a lot of different flavors. Kimchi is the huge new thing people are putting into queso. Ice cream, when you kind of take liberties with it, is good with a queso base.

JC: I guess by Italian rules we could say fish.

LF: Yeah. But shrimp and crawfish make awesome queso! I don’t know if there really is anything that it can’t improve upon.

El Paso-style Huevos Rancheros

Makes four servings.

1 tablespoon unsalted butter

2 tablespoons diced yellow onion

1 jalapeño, seeded and diced

2 cloves garlic, minced

¾ cup diced grape tomatoes

1 tablespoon cornstarch

¾ cup whole milk

½ cup water

8 ounces yellow American cheese, shredded

½ teaspoon kosher salt

½ teaspoon ground cumin

¼ teaspoon cayenne

8 crispy tostadas

2 teaspoons vegetable oil

8 large eggs

Chopped fresh cilantro, for garnish

Hot sauce, for serving (optional)

In a medium saucepan, melt the butter over medium-low heat. Add the onion and jalapeño and cook, stirring occasionally, until softened, about 5 minutes. Add the garlic and tomatoes and cook for 30 seconds longer.

Whisk together the cornstarch, milk, and water until well combined, then pour into the pan. Bring to a simmer, stirring constantly, and cook for a couple of minutes, until thickened. Add the cheese, turn down the heat to low, and cook, stirring, until the cheese has melted. Stir in the salt, cumin, and cayenne, then taste and adjust the seasonings, if you like. Keep the queso over low heat, stirring occasionally to prevent burning.

Place two tostadas on each of four plates.

In a large skillet, warm 1 teaspoon of the vegetable oil over medium heat. One at time, crack 4 eggs into the skillet, lightly salt them, and fry until the whites and yolks are set to your preference, about 2 minutes for over easy, 3 minutes for over hard. Place a cooked egg on each tostada. Repeat with the remaining oil and eggs.

Stir the queso and evenly drizzle over the eggs. Garnish with cilantro and serve immediately with hot sauce, if desired.