On Friday night, fans lined up outside of Austin’s Fair Market event space chasing down a rumor. Word had it that the space would be playing host to a surprise pop-up performance by Frank Ocean, who had unexpected dropped a new single only a few days earlier.

This particular whisper seemed fairly plausible. Artists like Ocean usually do swing by SXSW when they have something to promote, and Fair Market is one of the prime locations for that sort of thing. Of course, rumor-based games of telephone that go nowhere are also a part of the SXSW experience. Ocean was nowhere to be seen in Austin during the ten-day conference.

But not only did Ocean not show up at Fair Market on Friday—nobody else did, either. Fans who chased down the rumor, queued up, and eventually entered the building were met with an empty venue. Fair Market, on Austin’s East Fifth Street, has been an important venue for SXSW in recent years. That’s where you’d go to see headliners like Kendrick Lamar, Diplo, Skrillex, Questlove, Fun., 50 Cent, Anderson.Paak, A$AP Rocky, and more. The idea that it would be dark on the Friday night of SXSW music, frankly, seemed almost more implausible than a surprise appearance by one of music’s most enigmatic figures.

Fair Market wasn’t the only empty space on a big night of SXSW. The Moody Theater at ACL Live, the venue that played host to megastars like Bruce Springsteen, Green Day, and Coldplay in previous years, was empty on Saturday. Pop-up venues that fans had grown accustomed to—the Hype Hotel, the Spotify House, or other brand-sponsored spaces that bring big headliners to the festival—simply sat this one out. A few years ago, brands like American Express and Samsung were throwing seven-figure paychecks at superstars like Jay-Z, Kanye West, and Prince. Last year, Drake popped by the Converse-sponsored Fader Fort for a headlining performance on the fest’s final night. This year, the surprises were fewer and the events were less exclusive.

SXSW is changing, but it’s not actually a bad thing. For years, the conference’s most unsolvable problem was that it was too big in ways that were fundamentally unsustainable, bringing crowds of badge-holders and attracting a veritable army of spring break thrill-seekers to a city that wasn’t built to contain them all. SXSW’s own economic impact reports continually show a growing event, even if the last year seemed to be more of plateau (from $315 million in 2014 to $317 million in 2015 to $325 million last year) than an event that’s continuing to climb the mountain, but for the average spectator, SXSW has seemed like a festival whose primary economy is FOMO.

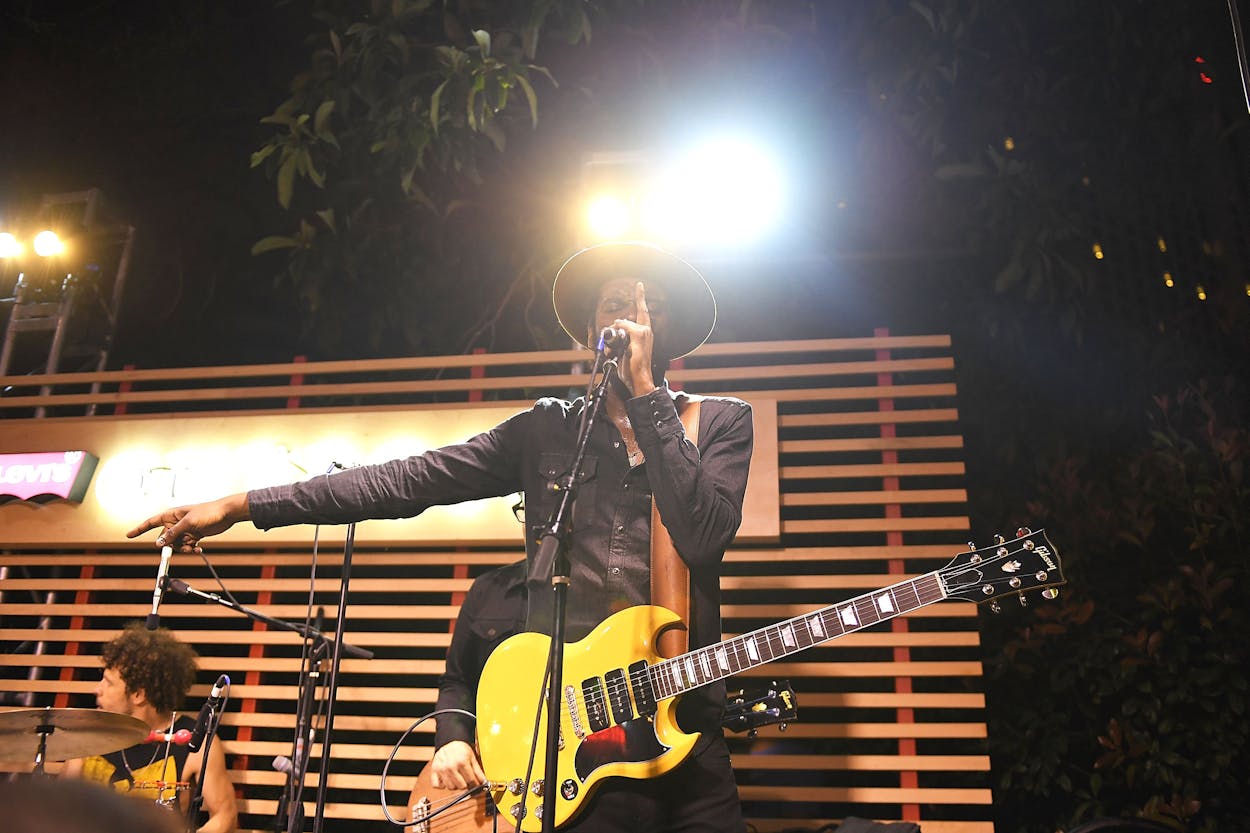

Not so this year. The big-name headliners playing exclusive gigs weren’t as impactful as in years past. This year, fans queued up for hours to see Solange, Lana Del Rey, Lil Wayne, Ryan Adams (who ended up canceling his set due to illness), At The Drive-In, The Chainsmokers, and other acts who, while successful, don’t come with the cachet of the Boss or Kanye.

This is healthy, given the alternatives. As it became clear that the scale of SXSW in its 2011 through 2014 iterations wasn’t something that could possibly sustain itself, the past couple of years felt much more precarious. Brands still showed up, the crowds were still there, but the festival’s ability to capture the attention of the entire world seemed to hinge more and more on the surprise appearances by superstars. The 2017 edition of SXSW wasn’t all that different from the 2016 edition, except that Barack and Michelle Obama anchored the early part of the 2016 conference, while Drake came by at the end to make sure that people who came to Austin to be close to the action could say that they almost caught a surprise set by a star. The question this year, without those blatant headliners, became: What does SXSW look like when nobody is paying the world’s biggest stars to show up?

There are a few ways that could have gone, and 2017 seemed to be the best possible outcome. Walking around downtown Austin during the festival, it was impossible not to notice that the streets were less crowded, that the lines were a little shorter, that the concentration of people in the same spots every single night had calmed down a bit. But also, the streets were crowded, the lines were long, the people excited to see Solange or Lana Del Rey still outnumbered the people who could get in to the venue. And that’s important, because SXSW needed to find a way to shrink without collapsing entirely. For years, observers watched the conference like it was a bubble about to burst—in 2017, it became clear that it’s more like a balloon with a slow leak.

Don’t take all of that to mean that the future of SXSW will be a return to its indie roots. That ship has sailed for reasons that go well beyond SXSW. During its indie heyday, SXSW interactive—now the biggest part of the conference—barely existed. SXSW film, which has become one of the more relevant film festivals in the U.S. was a scrappy afterthought. And SXSW music existed in an industry where artists came to the festival looking to sign with a record label so they could “make it.”

In 1996, Whiskeytown—Ryan Adams’ first band—had one of those mythical SXSW experiences in which an act captures the attention of the entire industry, signs a record deal, and sets out on a steady path toward fame and fortune. Whiskeytown released two major label albums, Adams went solo and became a superstar, and SXSW is such an integral part of his success that his relationship with the festival continues to this day.

Today, the closest analogue you might find to that experience was that of California rapper Vince Staples, who played what felt like a hundred shows at the festival in 2016, ranging from mid-afternoon sets at day parties to brand-sponsored gigs in hotel ballrooms to official SXSW showcases. He was busy, he got in front of everybody that a young artist wants to get in front of, and his career blossomed as a result: This year, when Staples returned to the festival, he played just one show, the exclusive Apple Music performance series on Thursday night. Getting in front of record label executives doesn’t do as much for your career in 2017 as it might have twenty years ago, but getting in front of ad agencies, event planners, brand managers, and other people who actually pay artists these days sure does, and those people are still at SXSW every year.

And the reality of the music industry makes it impossible to imagine a SXSW that isn’t heavily brand-sponsored. Music is almost entirely brand-funded these days, so the music conference has to be, too. And if brands—and the people who work for them—want to remain relevant, they’ll keep trying to tap Vince Staples, or the festival’s Grulke Prize-winning Lemon Twigs (an award that recognizes the festival’s breakout acts—previous winners included Anderson.Paak and Leon Bridges), or whichever other rising act made a big impact on SXSW. That makes for a delicate balance—the abundance of brand dollars in Austin can get tacky and overwhelming—but also, nobody else is going to pay Solange or Lana Del Ray whatever YouTube and Apple Music paid them to come do their sets.

And the brands were still there at SXSW—they just acted differently than how they had in the past. The Fader Fort, which has long been one of SXSW’s premier events—bringing Drake, Sam Smith, Chance the Rapper, and more—announced this year that it would be “going back to its roots with a more intimate venue space,” which is publicist-ese for “spending less money at SXSW.” Spotify skipped the Spotify House, instead integrating their technology into the official SXSW app. Bud Light didn’t do a week-long intensive array of shows, but did show up on Saturday with The Roots to host a jam session featuring Shakey Graves, T.I., Brandy, Rae Sremmund, Method Man and Redman, and more. Other brands picked up the slack, too. Amazon Prime took over the Market & Tap Room on Third and Colorado for a multi-day activation that brought music, TV, drones, and Hugh Hefner’s son to SXSW.

Then, of course, there’s Garth Brooks.

The best-selling recording artist of all time was announced as a keynote speaker for the festival a few weeks before it started, and the smart money for a surprise pop-up gig from the star would have been on ACL Live on Thursday night, when the CMA Songwriters Showcase had a bill featuring two Nashville songwriters—including one of Brooks’ recent scribes—as well as Lady Antebellum in the headlining slot. There was space for more music at the venue that night, though, and Brooks would have made sense.

He didn’t drop in for an exclusive performance for 2,750 fans in the theater, though. (He did, the night of his keynote, head to Broken Spoke.) Rather, SXSW announced that Brooks would be the headliner for the final night of its free, open to the public, no badges required concert series at Auditorium Shores.

That was a big deal for a few reasons, and at the top of that list is that, while bringing artists to town for exclusive sets in tiny venues is one of the things that brands pay for—controlling the venue, and who has access to it, allows them to create the sort of signature, prestige event that brands are desperate to be attached to. Brooks, one of the biggest stars of the conference, instead performed for 20,000 people, with the only criteria for tickets is living in an Austin zip code.

Austin’s long had a love/hate relationship with the festival. It screws up traffic, overwhelms the downtown area, makes travel difficult, and generally disrupts people’s lives—but its economic impact also helps fund public transit for the year, and everybody from waiters and baristas to pedicabbers and rideshare drivers to part-time security temps outside those tiny, exclusive venues pay their bills for months to come because of the money they made during SXSW.

So throwing Brooks to the rest of Austin, the people who might not directly benefit from SXSW, is pretty sweet goodwill gesture. It also suggests a balance that SXSW ought to try to keep in mind as it moves forward, as it looks for ways to maintain the prestige that it’s had in years past while looking for a more sustainable future. SXSW has benefitted from the association with Lady Gaga playing exclusive Doritos showcases and Jay-Z and Kanye packing the now-defunct Austin Music Hall for Samsung, but those things have also been largely out of the festival’s control. Sponsoring a set by a megastar keeps the megastars at SXSW, which has a trickle-down effect—if Garth Brooks is still at SXSW, it’s probably worth it for Apple or YouTube or Amazon or whoever to pay other big names to show up—but opening it to the public in that way also swaps FOMO for something more participatory.

This past festival gave us a look at what a shrunken SXSW might be like as it evolves into whatever it’s going to be in the future. And what can we take away? Let the brands keep bringing in the exclusivity, but leave the conference with room to breathe. It turns out, it might work pretty well.