In the aftermath of last year’s Dylann Roof massacre, Houston once again confronted its Confederate past. There were calls to remove certain statues from city parks, to rechristen certain streets, and to rename several schools dubbed after Confederate leaders.

As of late last year, that list of educational institutions was comprised of high schools bearing the names of Confederate president Jefferson Davis, postmaster general John Reagan, and top commander of the Confederate Army Robert E. Lee. Also on the list were middle schools named after rebel generals Stonewall Jackson, Texan Albert Sidney Johnston, and Dick Dowling, the Irish-born Houstonian whose small batallion of cannoneers once staved off an amphibious federal invasion of East Texas.

It seemed like a judicious plan. Although some of those men made contributions to Houston (or Texas) above and beyond their Confederate service, it was hard to contend with a straight face that any of them would be so honored had it not been for their taking up arms (or otherwise serving) the Confederacy. As for Dowling, the only Houstonian of the bunch and the town’s first municipal hero, even if his name were stripped from that school and his namesake street dubbed anew, the local Irish community could still rally around his statue.

This month the list grew to include two more schools. HISD board president Rhonda Skillern-Jones announced that the list of “schools linked to Confederate leaders” to be renamed had grown from six to eight. The process to rename the schools will begin at a meeting Thursday night.

The two new schools? Henry Grady Elementary and Sidney Lanier Middle School.

First, a bit about Grady. Born in Georgia in 1850, Grady was 15 when the Civil War ended, so a Confederate leader he was not. Instead, Grady made his name as a newspaperman in Atlanta, where he became an early evangelist for the idea of “a New South”: goodbye to the sleepy days of the Land of Cotton, and hello diversified agriculture and the hustle and bustle of Northern-financed industrialism. That’s all well and good, but there is no getting around the fact that Grady did cling to one facet of the antebellum South: white supremacism. Check out this excerpt from an 1888 speech:

. . . the supremacy of the white race of the South must be maintained forever, and the domination of the negro race resisted at all points and at all hazards, because the white race is the superior race.

Now contrast Grady’s George Wallace/David Duke-like rhetoric with the words of Sidney Lanier:

Liberty, patriotism, and civilization are on their knees before the men of the South, and with clasped hands and straining eyes are begging them to become Christians.

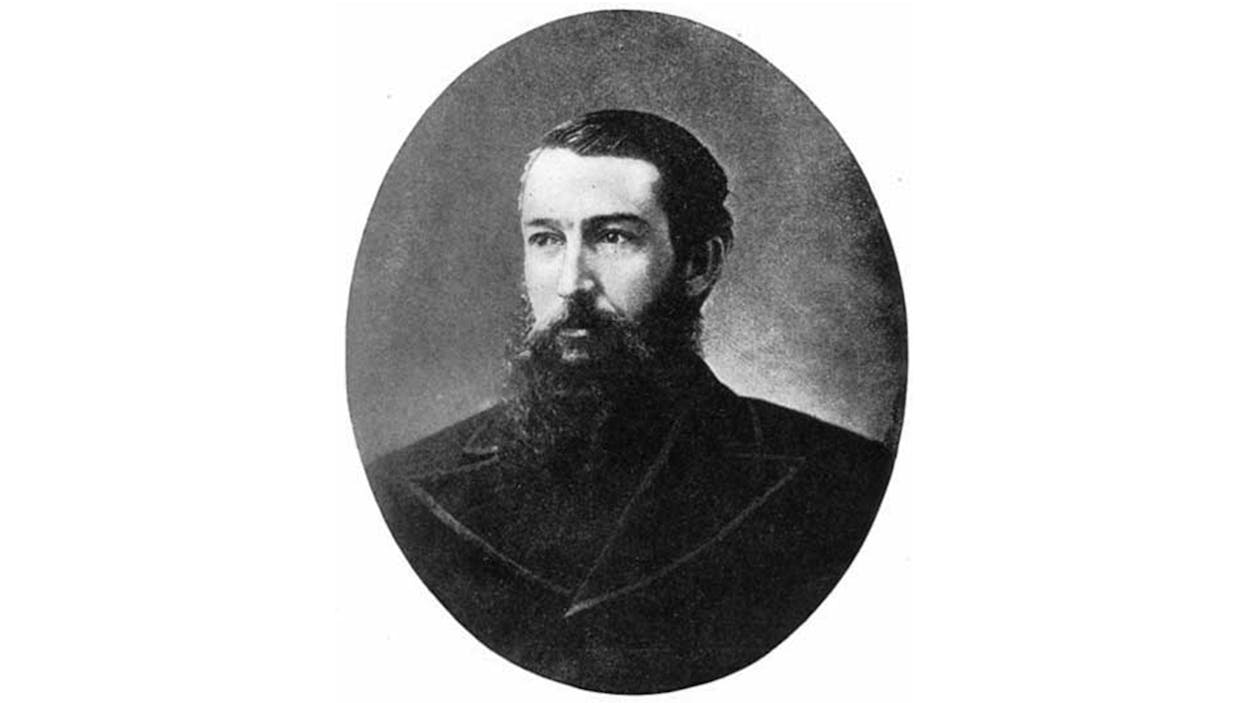

Lanier served in the Confederate Army, but as a 19-year-old buck private, and later as a pilot on ships used to smuggle cotton past federal blockades. He wasn’t a leader, nor was he an apologist for slavery, white supremacy, or even the “Lost Cause,” which he later gently mocked as a case of mass hysteria extending from Virginia through East Texas.

“The whole South was satisfied it could whip five Norths,” Lanier reminisced two years after Lee’s surrender. “The newspapers said we could do it; the preachers pronounced anathemas against the man that didn’t believe we could do it; our old men said at the street corners, if they were young they could do it, and by the Eternal, they believed they could do it anyhow; the young men said they’d be blanked if they couldn’t do it, and the young ladies said they wouldn’t marry a man who couldn’t do it.”

But they couldn’t. Far from it. And their defeat was justified, according to Lanier. “As soon as we invaded the North and arrayed [their] sentiment against us, our swift destruction followed,” he wrote.

Paraphrasing Robert Earl Keen, Sidney Lanier was no kinda rebel, and was not remembered as such in his lifetime or after. Instead he was renowned as a poet and a musician, or in the words of Jim Henley, legendary former Lanier Middle School debate coach and 2006 liberal Democratic candidate for U.S. Congress, Lanier was “a renaissance man,” one who attempted to mesh his words with his tunes, music he created on the flute, banjo, organ, piano, violin, and guitar. (Lanier once pithily described music as “love in search of a word.”)

“He’s the kind of example to which we would wish all of our students to aspire,” Henley says. “Though he was a private in the Confederate Army and for four months a prisoner of war, he was not a leader in the Army. Not a general, not a decision-maker. And I’ve been reading his entire body of work, and in no case does he lament the end of slavery, and in some cases he rejoices over the end of slavery.”

That’s when Henley recites the lines above about clasped hands and straining eyes and the men of the South begging to become Christian.

Henley had been in support of name changes at other schools, but Lanier didn’t quite add up. “There’s no way this sensitive poet, scholar and musician should be thrown in with generals who were fighting to maintain a totally corrupt and immoral system,” Henley says.

The school is smack-dab in the heart of Montrose and is likely Houston’s most liberal campus, but certainly lands that distinction among public junior highs. Yet Henley says that nobody he knows supports the changing of the name. (Though some do long for the school to do away with its less-than-ferocious team name, the Purple Pups.)

Here’s the thing. Despite Grady’s justified inclusion on this list of historical damnation, it seems more and more that the only mortal sin is to have sworn allegiance to the Confederacy. So long as you did not bear arms against the Union, your memory is safe, no matter if you engaged supported secession all your life and spearheaded genocidal campaigns against Native Americans (Mirabeau Lamar); owned a dozen or so slaves at the time of his death (Sam Houston); finagled to introduce large-scale slavery into a sovereign nation where it had hitherto been forbidden (Stephen F. Austin); engaged in the capital offense of slave-smuggling (Jim Bowie, James Fannin); expressed disgustingly racist views in print (Davy Crockett); fathered children with a slave woman (Thomas Jefferson); or joked that the best way to contain the AIDS crisis was “to shoot all the queers” (Louie Welch).

All of those men have schools still safely named after them in HISD, as does Oran Roberts, who shepherded Texas out of the Union as president of the 1860 Texas Secession convention and later founded and led a regiment of Confederate soldiers. Why Roberts gets a pass is a mystery. Not only did he serve as a Confederate colonel, but immediately after the war, he stated his goal was to help found “a white man’s government” and “keep Sambo from the polls.”

And then there was William Barrett Travis, who abandoned his wife and child, owned a slave, captured and returned runaways for a fee, and died with syphilis thanks to his rampant womanizing; and Woodrow Wilson, whom some on both the right and the left believe was the twentieth century’s most racist president.

Oh, and there’s Mark Twain, who served for two weeks as a lieutenant in a Confederate Missouri militia unit before deserting. Although some experts have claimed Twain was an ardent believer in the Confederate cause in his younger years, works like Pudd’nhead Wilson and Huckleberry Finn, not to mention his own words outside of novels, showed that some people, even then, could evolve beyond the racist mores of their time and place. As Twain put it late in life, the war had been “a blot on our history, but not as great a blot as the buying and selling of Negro souls.”

Motivation counts. Unlike naming a school after Davis, Lee, or Jackson, Lanier was not a raised middle finger to the hated Yankees, but a salute to Southern literature, such as it was in 1929. The naming of Lanier took place at a time in which, at least on what was then the southwestern fringe of Houston, the city was in one of its rare literary moods. Around the same time, the district dedicated a school to that other great Southern literary icon: Edgar Allen Poe. Streets adjoining Lanier or very close by were streets named after Rudyard Kipling and Nathaniel Hawthorne. (Elsewhere around the city, the district was naming schools after the poet Robert Browning and the children’s storyteller Eugene Field; around the same time, near the newfangled suburb of West University Place, the city was grading out streets with names like Shakespeare, Dryden, Wordsworth, Chaucer and Addison.)

“If I could find one statement of Lanier’s that sounded anything like [Henry Grady’s racism], or if Lanier had been a real leader in the Confederacy, I would stand silent in the corner while they changed the name,” Henley says. “I just think this has been brought up [by HISD] without thorough investigation.