Before President Obama got to the stage at the Long Center for his SXSW Keynote interview with Texas Tribune boss Evan Smith, there was another keynote conversation between Oak Cliff native Casey Gerald (who founded, and then recently disbanded, the organization MBAs Across America) and Texas Monthly‘s Jeff Salamon. Gerald was the warm-up act; Obama the main event—but when Gerald was asked what he would say to the president if he got the chance to talk with him, he said he’d tell him to say what he would say if he weren’t afraid.

“Obama doesn’t need my advice,” Gerald acknowledged before explaining that, he suspected, Obama was at SXSW with a specific agenda: Namely, to put a stamp of approval on the tech industry, and ask them to help save the country. Gerald seemed unenthused about the prospect, and—while that sentiment might not be popular among the SXSW rank and file—he’s not alone in that. The political climate at the moment isn’t necessarily one that makes asking “Please save us” to the Zuckerbergs and Ubers of the world a popular one. In Austin, the tension between the tech world and the people who feel alienated by it is approaching fever pitch; nationally, surging presidential candidates like Bernie Sanders and Donald Trump are winning primaries and gaining massive popular support and expressing sentiments like “we need to raise taxes on the wealthy” and “people should boycott Apple”—two different spins on a sentiment that the folks who come to Austin for SXSW tend to see as an existential threat.

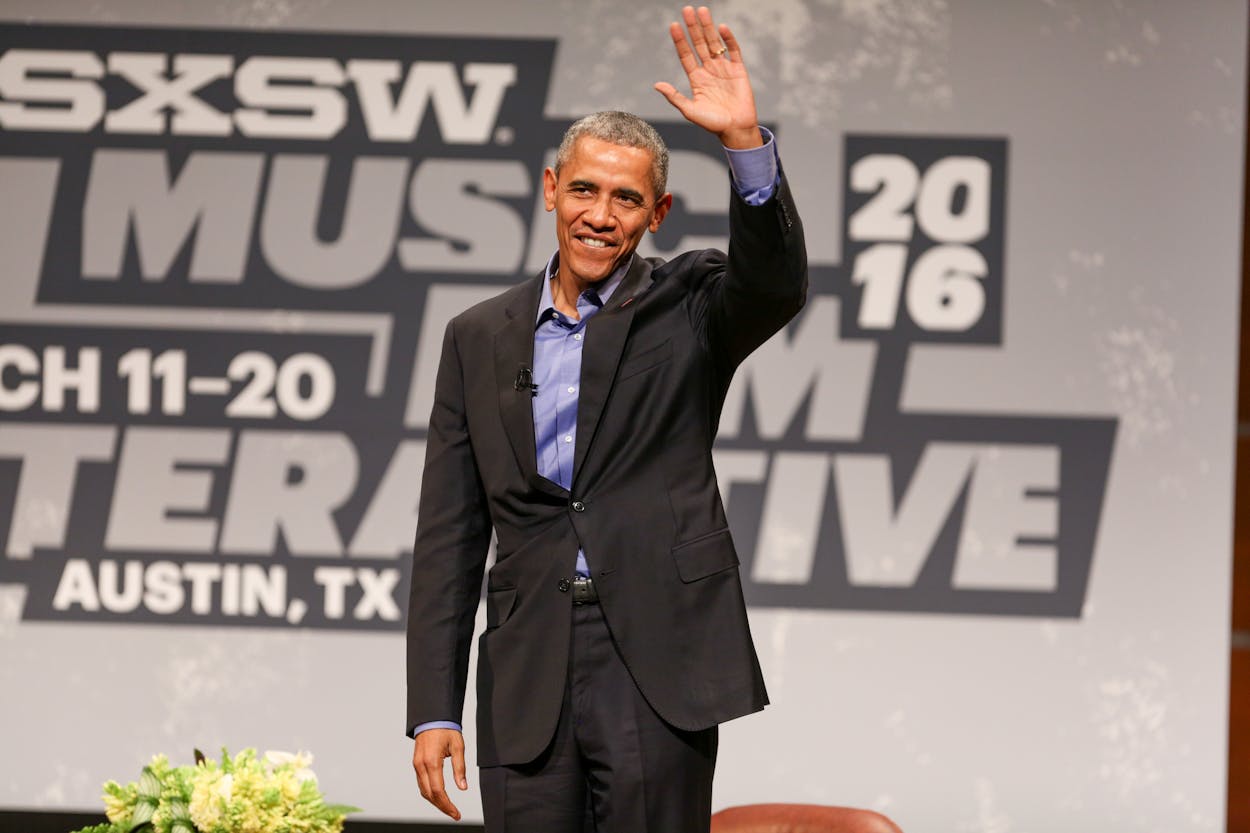

Obama showed up late—after a well-publicized stop at Torchy’s Tacos (which, we think, probably means that San Antonio is the official winner of the Taco Summit), he took the stage a little after 3 in the afternoon on Friday. His opening remarks reflected more of that tension than Gerald might have expected: He spoke of both the opportunities and challenges that the tech world presents to the country, and to the world. He praised the way that FAFSA had been streamlined through technology, or how the social security application process could now be completed online—and, looking to the future, the opportunities presented by personalized medicine, and how the sort of research that could change lives is done by the sort of people who are at SXSW. “The reason I’m here is to recruit all of you,” he said. “As I’m about to leave office, how can we come up with new platforms, new ideas, and new approaches across disciplines and skillsets to solve some of the big problems we’re facing today?”

Smith challenged the president on the culture of tech—”fail fast,” he put it—and the culture of government (“big and bloated”) on how they can co-existed. Obama mentioned the lessons he learned from the Obamacare rollout, where the Healthcare.gov website failed. “It was an outdated, bloated, risk-averse system that didn’t work well,” he said. “We brought in a SWAT team of all of my friends from Silicon Valley and Austin to fix it, which we did. We realized we could build a world-class technology office in government that helps across agencies, and we’ve done that with U.S. digital services.”

The way Obama described the U.S. Digital Services made it seem more like a tour of duty for sharp coders who’ll eventually find their futures in the public sector—”Some stay for six months, some for two years”—and suggested that the appeal of helping their fellow citizens by doing the work was enough to keep the job attractive, at least for a time, to these bright developers.

Obama addressed other issues, including the sort of blue-sky idea that SXSW is good at: Could we get to online voting in the U.S.? (Not in Texas, he said, because “the people who govern Texas” don’t want more voters.) He also made a case for the very existence of government to a crowd that tends to lean more libertarian than most: “I could find the most libertarian, government-hating person in the room, and tell them how government works for them,” Obama said, “He’s probably out there checking the weather on his phone, and it’s getting that information from a government satellite.” He acknowledged that the point-of-contact with government that people have—at the DMV, say, or the IRS—can create negative associations, and one of the challenges government faces is to use technology to make those things easier and less stressful.

One of the challenges presented by the tech world that Gerald seemed to suggest by his comments before the president’s keynote is the inequality posed by an increasingly connected world, and Smith asked about that at its root: poor households, especially Latino and African-American households, often don’t even have Internet access. It’s fine, certainly, to talk about the need for more software engineers to work within government to improve systems and help develop the tech infrastructure of the U.S.—but the opportunities presented by the tech world also create gaps that are easy to ignore.

“The private sector doesn’t have to educate the poorest kids,” Obama said when pressed on this point. “If you have aging, sick veterans, the private sector may not serve them, or try to get the homeless off the street. Those are government problems. You’re not going to solve them the way you’re going to get the perfect price on your ticket to Cancun. But if we can re-conceive our government so that the interplay between the private-sector, non-profits, and government are opened up, and we use technology, data, and social media in order to join forces around problems, then there’s no problem that we face in this country that’s not solvable. The key is to have incredible talent like is gathered here to focus on it. It’s not enough to focus on ‘what’s the cool next thing’—we have to figure out how to harness the cool next thing to make sure that everybody in this country has opportunity.”

That’s a fine idea, and an appealing way to frame the issues at work here. It’s also pretty vague in the specifics. The idea that getting more people from the tech world engaged in government is a good start—without it, at the very least, government is going to end up lagging behind the private sector in ways that threaten to leave that poor kid uneducated, or that aging sick veteran uncared for. But outside of online voting, the big-picture ideas that come out so well at SXSW weren’t on display in Obama’s SXSW keynote. That’s perhaps to be expected—sitting presidents rarely get creative when they talk about this sort of thing, and he’s trying to reach a broad audience. But it’s hard not to see POTUS speak at a conference where a lot of smart people who are looking to reinvent the world are lined up for a half mile to hear him, and not give them the sort of blue-sky idea that they’re getting elsewhere at SXSW, as anything other than a missed opportunity.

It’s exciting to have had Obama at SXSW. SXSW Interactive director Hugh Forrest described it in his introduction as “one of the most special events, if not the most special event, in SXSW’s thirty-year history,” and he’s not wrong about that. But ultimately, Obama had the opportunity to discuss the way that government of, by, and for the people interacts with the private-sector tech industry that gathers at SXSW. The conversation ran long—after Smith asked about encryption and Apple, Obama gave an exhaustive answer, and Smith declared the session at an end. “I’m the president, so I’m going to say one more thing,” Obama said, before he finally did make his pitch, urging people go to WhiteHouse.gov and join the mission to innovate ideas. He offered another specific example—a program that distributes diapers in low-income environments—before calling it a day. “If the brain power and the talent that’s at this conference takes up that baton,” he said, “then I’m going to be really confident about the future of this country.”