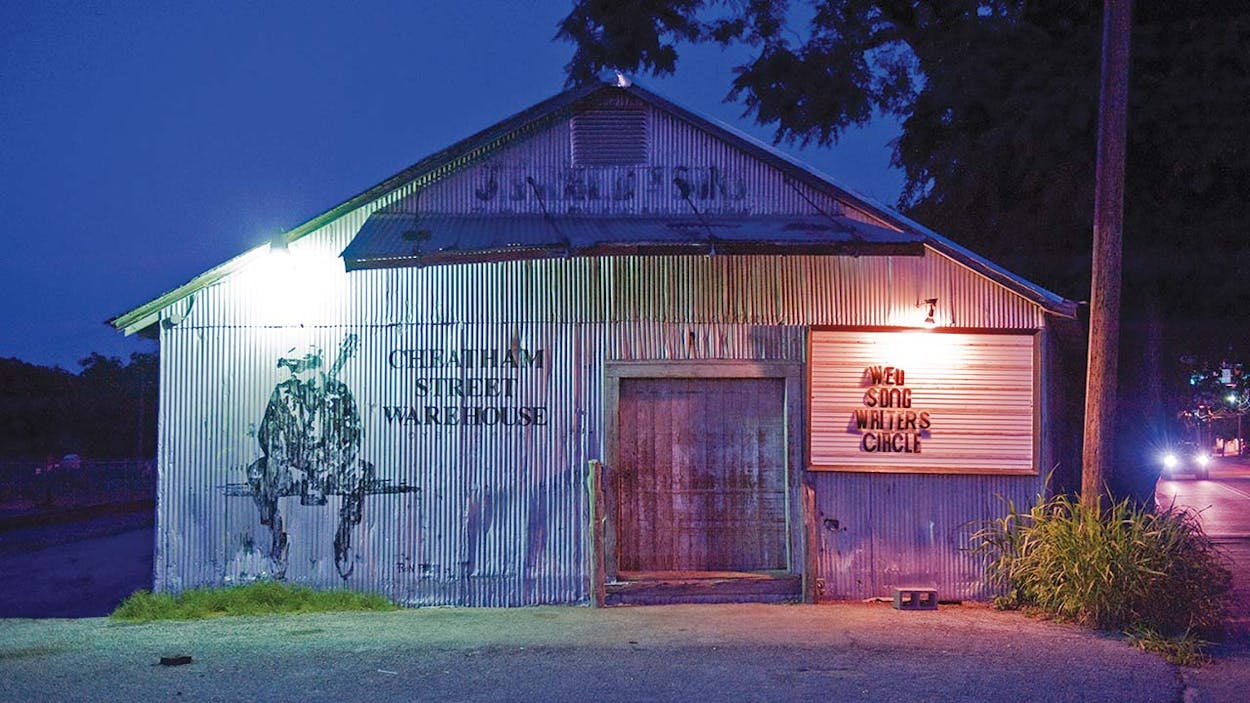

Of all the honky-tonk stages in Texas music history, perhaps none has launched more careers than the small expanse of plywood at Cheatham Street Warehouse in San Marcos. It’s a modest space, roughly twenty-five feet wide and fifteen feet deep, with a single step elevating it from the dance floor. The threadbare carpet is beer-stained and peppered with cigarette burns, and an eponymous street sign and a softly lit Texas flag serve as the only ornamentation against an otherwise black backdrop. But since 1974, the simple stage has been fertile soil for acts such as the Ace in the Hole Band (later joined by a young agriculture student named George Strait), Stevie Ray Vaughan, Hal Ketchum, Tish Hinojosa, Bruce Robison, Terri Hendrix, Hayes Carll, and many, many others. Under the stewardship of the venue’s founder, the songwriter Kent Finlay, nobodies went from fumbling through original compositions to cultivating careers that have altered the musical landscape of Texas forever.

But when Finlay died on Texas Independence Day in 2015, the future of the historic venue became uncertain. The 105-year-old building, originally built as a grocer’s warehouse, was in grave need of expensive repairs and structural improvements just to pass code. Though Cheatham Street powered on under the guidance of Kent’s children, Jenni, Sterling, and HalleyAnna, as well as the nonprofit Cheatham Street Music Foundation, it became increasingly clear that more resources were needed to sustain the business.

Late last December, a press release announced that Randy Rogers—one of the beneficiaries of the stage’s career-making powers—along with partner KRR Entertainment, were the new owners of Cheatham Street Warehouse. The news was well received by members of the San Marcos music community. As Richard Skanse of Lone Star Music recently wrote, “Out of all the songwriters and country stars to have launched their careers out of Cheatham Street Warehouse, perhaps no artist has ever been more forthcoming about their debt of gratitude to both the San Marcos, Texas club and its founder, the late Kent Finlay, than Randy Rogers.”

The Randy Rogers Band’s debut album was recorded live at Cheatham in 2000, and when the band inked a major-label deal a few years later, it was under the honky-tonk’s familiar tin roof with Finlay by their side. Over the decade or so that followed, Rogers and his mentor stayed close. On his third album, Rollercoaster, Rogers cut a Finlay original (“They Call It the Hill Country”), and the title of his latest record, last year’s Nothing Shines Like Neon, is a nod to another one of Finlay’s songs. Not a year has gone by since the band’s inception that Rogers didn’t return to play a few typically sold-out shows at Cheatham Street. Now Rogers hopes his acquisition of the venue will allow him to keep his friend’s dream alive and give back to the place that gave him his own break.

I spoke with Rogers the day before he flew to Washington, D.C., to play an acoustic gig at the Texas Inaugural Ball. “I’m going to wear my best shirt,” he told me, then added with a laugh, “and try not to speak my mind.” But before polishing his boots for the Washington bureaucrats, Rogers was rolling up his sleeves to do some work on his new venue.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

Christian Wallace: You got your start in the music business by playing at Cheatham Street. Could you talk a little bit about those early days with Kent Finlay and how that relationship formed?

Randy Rogers: I moved to San Marcos in 1996, when I started college. Cheatham reopened in 2000 [it operated as a mostly Tejano venue under different owners from 1988 until New Year’s Eve 1999, when Kent held a grand reopening, announcing on the marquee that it was “Under Old Management”]. At the time, I was listening to a radio station, KCTI, out of Gonzales. Jeremy Halliburton had a Sunday night kind of back-porch show, where he was spinning the guys who were making records in Texas. I had some neighbors and we’d all listen and play guitars till five in the morning. Advertised on that station was Kent Finlay’s Songwriter Night on Wednesdays. I’d been writing songs since I was a kid, but when I heard that I thought, “You know, it’s time for me to start playing my own songs.” So, I went down to Cheatham, walked in with my guitar, and, after playing that first night, Kent came up to me and said, “Hey, who are you? Would you like to come back next week?” And that began our friendship.

CW: You remember what song you first played for him?

RR: Yeah, I played a song called “Lost and Found.” I’d just written it. I was eighteen, nineteen years old, had my first college girlfriend. I was just a kid looking back.

CW: So Kent came up to you after your set and invited you back. How did it develop from there?

RR: Well, the next week I came back. He told me to, so I did. About a month later, we had lunch at Garcia’s across the street, and he said, “Look, I think you’ve got a gift. Stick with it, and I’ll be there as your supporter along the way.” He started talking to me about forming a band and what that meant, and how to structure it. He was a mentor from day one, honestly. He gave me hope. He gave me my first stage. Opened my first door in the business. He was like my musical father, in a sense.

CW: And how did the Randy Rogers Band come to be?

RR: Kent said, “If you start a band, I’ll give you Tuesday nights.” So I started a band with some local guys. We started playing there every Tuesday night. Kent would tell me things like, “Tell every friend to drive their own car, so the parking lot looks full.” I don’t know how many times I got in trouble for hanging posters on [the Texas State] campus without a permit. We tried every trick we could to get people there.

CW: Having Tuesday nights is not an insignificant deal at Cheatham Street. That’s the slot Ace in the Hole played when they first got started. Stevie Ray and the Sexton Brothers used to play that night. It’s got a steep legacy of great acts cutting their teeth on Tuesday nights. He must of had a lot of confidence in you to offer that gig to a brand-new band. Where did it go from there?

RR: At the time, he and Diana [Finlay Hendricks] were still married. She put together my first ever press release to mail out to other venues. I played Wichita Falls, then Fort Worth. Those were the first two places I played outside of San Marcos. I called the clubs and said, “Hey, I wanna play here. Call Kent Finlay if you have any questions.”

CW: That’s a pretty good person to vouch for you. Did you realize at the time that this was going to lead to a lifelong career?

RR: I’ve been playing music since I was a kid. I played oprys around my little hometown [Cleburne]. I wrote songs. I played in church. I dreamed about it for a long time. I mean obviously [when we started the band] we were in college, we were young, we were having a good time, but—and I think if Kent were here and you asked him the same question, he’d agree—I always looked at it as a business, as a way to make a living. I dreamed about it, but I also believed I could do it. I’ve always approached music as two different things. There’s music, and there’s music business. Kent was the first person that taught me that. I feel like from day one I was determined to win in the music business side of things. Whereas music isn’t a competition, the music business is a beast. That’s why purchasing Cheatham Street Warehouse—I feel like I’m the man for the job. I feel confident in saying that.

CW: Speaking of the business side of music, people who knew Kent often talk about how generous he was, especially to the artists who played at Cheatham. But, because he cared so deeply about the art of songwriting, he sometimes made decisions that weren’t necessarily favorable to his bottom line, and that meant he struggled at times to keep the lights on.

RR: I think Kent was first and foremost a promoter of young talent. He was a promoter of people who believe in music and songs and art. Him having a venue to support people who were not afraid to take risks was more important to him than making a buck. For as long as I knew Kent, he believed in the greater good of all people. He embodied everything that creativity and music is supposed to be about. And to a fault, I can say that I’m not Kent Finlay. I’m not necessarily the type of person that every single day puts the “sake of the song” and the artistic merit of being alive first. Like we were talking about Hondo [Crouch, the patron saint of Luckenbach] before we started recording, Kent kind of became that. There are very few people who are able to live in that world. That’s another important thing to say: I’m not trying to take over Kent’s legacy. I am, however, trying to make sure that with the growth in San Marcos and the way that the economics of our city are playing out, that Cheatham Street doesn’t go anywhere, that it is a harbor for young songwriters, that it’s a home for everyone that wants to come hear live music and dance and live like it’s 1974. But I’m not trying to be the next Kent. I’m trying to make sure that what Kent did and what he meant to so many people never goes away.

CW: While you’re continuing what Kent started, I’ve also read that there will be some changes. Do have an idea of what some of those changes will look like?

RR: There are some things that have to happen to make it up to code—like a fire suppression system, things that are kind of expensive—to continue to have shows there. My plans are to do live music as many nights a week as we can, support local talent as well as touring talent, expand the venue with a permanent patio, and eventually offer some kind of food service. Things like that—things that are pretty simple. Cheatham Street already has its own identity. I don’t have to create anything. It’s like when I write a song, I don’t try to reinvent songwriting, I just try to write sad country songs.

CW: With an expansion planned, do you foresee booking bigger acts in the future?

RR: Yeah, we’re trying to give San Marcos a viable dancehall. I still dance when I go out, and I know I’m not alone on that. I think once we get the patio, and once we do the improvements to the bathroom and things that the city wants us to do, I think we can increase our certificate of occupancy, which is how many people we can sell tickets to. And once we can sell around six hundred tickets or more, I think we’ll attract acts from all over the country. It will make it more economically feasible for them to stop in San Marcos instead of playing a show in Austin. That is a goal above and beyond: I want the best of the best playing Cheatham Street. I want the most talented newcomer and the oldest old fogey on the block who is the greatest songwriter that we all look up to to play here.

CW: What does Songwriter’s Night look like going forward?

RR: Songwriter’s Night is going to stay right here. It’s not going away. Sterling [Finlay, Kent’s son] is still going to run it on days that he can be here. The whole reason I have a band is Songwriter’s Night. It’s a staple and will remain a staple under my watch.

CW: Are there any songs you’ve written that were directly inspired by Cheatham Street?

RR: Let’s just say there’s one I’m working on right now that will be unveiled soon. It’s about Kent and about what he did for all of us, not just me. I think that will be a good start to a new chapter at Cheatham Street. Like I said, I’m forever indebted to Kent Finlay as a human being, so that’s the song I’m trying to write right now.

(Video by Charlie Stout)