This weekend my daughter decided she wanted a wall of her room to be covered in maps. That sent me rummaging through my closet where I have stocked a couple hundred, many of them given to me over the years by my packrat grandparents.

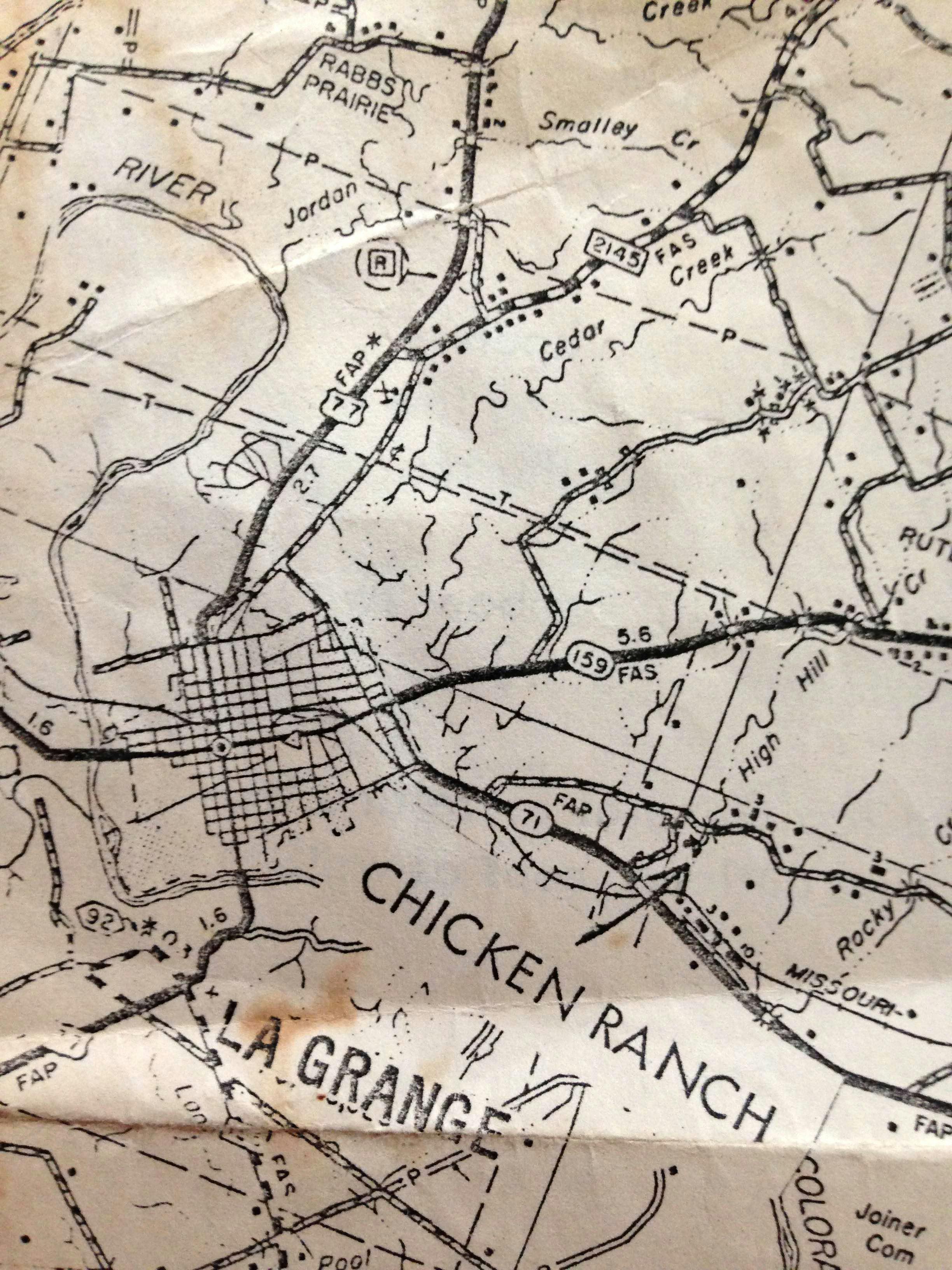

The one you see here is the most mysterious. On the map, which appears to be torn out of a book, the infamous Chicken Ranch is as prominently marked as anything else.

Flip it over, and here is what it says:

Here it is — bluebonneting, beer-drinking and road rallying time again. As with last year, you should endeavor to find your way to Stone Tree by driving on rural roads only. Consider these routes.

There follows four different routes out of Houston to Round Top, where apparently this Stone Tree was located. (“If you get mixed up, stop anywhere and ask directions,” we are advised as pre-GPS travelers.)

We are also given a few quaint “travel hints”:

Driving time at 55 mph and no stopovers will be a little more than two hours. Unless you get excellent mileage, you’ll probably need to top up your tank along the way somewhere to get back to Houston. Gas has been readily available in the past.

Those of the Beer-drinking, bluebonetting road-rallying persuasion are also advised to stop at Winedale’s Stagecoach Inn, today the centerpiece of the UT-affiliated Winedale Historical Complex. (It’s part of the Dolph Briscoe Center for American History, which in turn takes its name from the man who officially shut the Chicken Ranch down.)

Other hints: antiquing in Round Top and visiting that town’s general store proprietor Bette Schatte; fishing for bass and catfish in the creeks and lakes; a malty pit stop in New Ulm’s apparently long-gone Parlour beer garden; and, of course, the Chicken Ranch:

For you history buffs, a pilgrimage to the Chicken Ranch, although closed, would be something for you to tell your grandchildren about.

I don’t know about that. Call me a prude, but I was not ready to tell my eleven-year-old daughter about the Chicken Ranch just yet, and it seemed odd to to imagine the day when I might tell her children all about The Best Little Whorehouse in Texas.

But it did set me to thinking. I knew of the musical and the movie, and I knew the song quite well (as a kid, when my dad used to crank it up on the car radio, I imagined that Billy Gibbons was an actual monster singing), and later came to know Houston reporter Marvin Zindler’s role in bringing the place to its end, but how much did I really know about the Chicken Ranch, America’s most famous bordello?

Not much, as it happens.

The History

Though there were bordellos in La Grange as early as 1844, the Chicken Ranch did not find its home until early in the twentieth century and did not take its infamous name until the Great Depression.

According to the Handbook of Texas, a woman going by “Jessie Williams” (though born Faye Stewart) bought the Chicken Ranch property, just outside of town and just ahead of a massive vice sweep on La Grange’s red light district, in 1915. Williams always cultivated a good relationship with the town’s power structure. She donated to worthy causes, sent care packages to soldiers in France during World War I, and assisted Fayette County Sheriff Will Lossein with his investigations. Miss Jessie’s girls were under strict orders to report any pillow talk of felonious activity to her, which she would in turn report to Lossein—who visited the cat house nightly, the better to keep his eyes on Fayette County’s underworld, such as it was.

As the Depression deepened, many of Miss Jessie’s clients could no longer pay in cash, so she began to accept barter, which often came in the form of chickens. “One chicken for one screw” became the house’s “poultry standard.” And so was born the Chicken Ranch. Miss Jessie became a small-scale poultry tycoon.

In 1952, Miss Jessie hired Edna Milton, the young woman who was to succeed her. The Chicken Ranch’s final madam had been born into dire poverty in Oklahoma in 1928, the eighth of eleven children, and just in time for the Depression and the Dust Bowl. She dropped out of school in third or fourth grade and was forced into an unwanted marriage at 16. That marriage produced a child who died shortly after birth. The marriage foundered and by the time she was 23, Milton was a prostitute working for Miss Jessie.

By that time Miss Jessie was suffering from arthritis, no longer able to wield the iron cudgel she used to keep rowdy patrons in line with as much authority, nor possessing the mental energy to run her house as efficiently. She saw a spark in Milton, savvy in spite of her lack of schooling. Miss Jessie handed off more and more of the running of the place to her, and by the time after Miss Jessie passed away at 80 in 1961, Milton had completed her training program. She bought the place from Miss Jessie’s heirs for $30,000 and became Miss Edna.

Miss Edna picked up right where Miss Jessie left off. She cultivated the same working relationship with Sheriff T.J. Flournoy that Miss Jessie had with his predecessor. She donated to many of the same causes Miss Jessie had helped nurture. She installed air conditioning and added a dining room.

At its peak, in the 1960s, there were 16 girls working in as many bedrooms. Drinking was not allowed, but Miss Edna would sell you a Coke for the princely sum of $1 or a pack of Luckys for 75 cents. Off-duty cops directed traffic in the parking lot. Much of the clientele came from nearby military bases and Texas A&M, where, according to legend, a Chicken Ranch trip was part of freshman initiation.

Miss Edna charged her customers $15 for fifteen minutes, and each of her workers was expected to have between five and twenty customers a day. Miss Edna took three-quarters of the cut, leaving many of the women to take home about $300 a week, which was a decent sum in those days.

That Song

Given its place in the classic rock canon and multi-generational ubiquity in pop culture, ZZ Top’s “La Grange,” their tribute to Texas’s infamous bordello, is not just their signature tune, but probably the most widely-recognized rock and roll song ever to emerge from Texas.

Some believe the song inadvertently helped bring about the downfall of the Chicken Ranch, but based on the band’s telling, it seems they had their own connection to it. Here’s ZZ Top’s bassist Dusty Hill, speaking, as only Dusty can, to Spin in 1985:

I went there when I was 13. A lot of boys in Texas, when it’s time to be a guy, went there and had it done. Fathers took their sons there. You couldn’t cuss in there. You couldn’t drink. I had an air of respectability. Miss Edna wouldn’t stand for no bulls–t. That’s the woman that ran the place, and you know she didn’t look like Dolly Parton, either. I’ll tell you, she was a mean-looking woman. But oil field workers and senators would both be there. The place had been open for over a hundred years, and then this a–hole decides he’s going to do an exposé and close it. And he stirred up so much s–t that it had to close. La Grange is a little bitty town, and little towns in Texas are real conservative. But they fought against it. They didn’t want it closed, because it was like a landmark. It was on a little ranch outside of town, the Chicken Ranch. Anyway, we wrote this song and put it out, and it was out maybe three months before they closed it. It pissed me off. It was a whorehouse, but anything that lasts a hundred years, there’s got to be a reason.”

What happened to it?

Area native Jayme Lynn Blaschke, author of an upcoming history of the Chicken Ranch, recently toured the grounds. Not much is left other than tumble-down ruins of the office and a few of the bedrooms in a pasture studded with prickly pear.

The Chicken Ranch’s common area left the premises long ago. In 1977, businessman Bill Fair III bought the parlor and its furnishings and trucked it to the Big D’s Greenville Avenue, where he joined it to an existing building and repurposed it as a discotheque/bar/restaurant with a chicken-heavy menu and none other than Miss Edna herself serving as hostess. The Dallas Chicken Ranch also featured barstools mounted on plastic bare female legs and peddled souvenirs such as T-shirts with the slogan “I had a ball at the Chicken Ranch.” Miss Edna cared not a whit about her outing as Texas’s most famous ex-madam. By that point, she noted, her parents were dead. “I don’t care what the rest of the world thinks of me.”

LaGrange Journal owner and editor Lester Zapalac was amused when he heard of the Ranch’s relocation and repurposing. “That’s kind of a cute idea,” he told the San Antonio Express-News. “Some of those people in Dallas are going to be embarrassed when they see their names or initials on those walls unless they are going to paint over them.” (They didn’t.)

Perhaps that prospect chilled the hearts of customers even more than the stated reason for the restaurant’s failure in January 1978: a literal lack of warmth. Fair apparently did not install adequate heating in the Greenville structure. “Nobody wants to sit around in a place that’s 50 degrees,” he said.

In June 1978, the furnishings were auctioned off. Noted Seguin Gazette-Enterprise columnist Ben Mikus:

At a public auction to dispose of the Chicken Ranch’s furnishings, one gentleman attending the festivities was heard to wonder out loud how the Chicken Ranch could survive two world wars and one depression near the country town of LaGrange and manage to turn a profit of up to $1.5 million a year, and then go bankrupt in Dallas in less than three months.

The gentleman’s companion, no doubt an astute disciple of human nature, was quick to point out that if there’s a product a man really wants, he doesn’t mind driving a few extra miles to get it.

Miss Edna went on to open a Chicken Ranch Bar on Dallas’s Lemmon Avenue, and after that too swiftly failed, she moved to Gladewater and got married. At some point around that time, she sold her story to Larry L. King, whose Playboy article spawned the Broadway hit musical and later the Dolly Parton and Burt Reynolds film, that, unlike the musical, Miss Edna openly hated.

After the death of her husband, Miss Edna remarried a man named Chadwell and quietly lived out the rest of her days in Phoenix, where she died four years ago.