Were it not for a fortuitous Uber ride taken by Dallas entrepreneur Jay LaFrance a little more than a year ago, the Longhorn Ballroom, arguably the most storied live music venue in the state, likely would have met the fate of another beloved Dallas live music spot, the Bronco Bowl, which was razed in 2003 to make way for a Home Depot.

The Longhorn Ballroom is perhaps most famous for holding one of only seven gigs the Sex Pistols ever played in the U.S., on January 10, 1978. (The band broke up a week later, and Sid Vicious died of a heroin overdose a few weeks after that.) The venue has a remarkable history of performances, though, by amazing musicians in a variety of genres spanning multiple eras.

There were country and western acts like Loretta Lynn, George Jones, and Merle Haggard, who played nine days after the Sex Pistols and shared the marquee with them. There were blues and soul acts like Otis Redding, James Brown, and Bobby “Blue” Bland, who Mick Jagger came to see play one night. There were punk and rock acts like the Ramones, Patti Smith, and George Thorogood, at whose show several beer-bottle fights broke out. And there were alternative and heavy metal acts, like Butthole Surfers, Flaming Lips, and Megadeth, whose RV was almost toppled by Rigor Mortis after the two bands got into a skirmish.

From 1950, when it opened as a home base for Bob Wills, the King of Western Swing, until 1990, when a 2 Live Crew show resulted in a melee, the Longhorn Ballroom was a rarity in Texas for its mix of quality and diversity. For more than twenty years, though, the Longhorn had sat largely unused, its Wild West facade languishing like an abandoned movie set. That is, until LaFrance tapped the Uber app on his phone.

LaFrance, a managing partner in an investment company, was on the way home from the airport, talking business on his cell phone. His Uber driver had learned from a previous rider that the owner of the Longhorn Ballroom, Raul Ramirez, was fielding offers. The driver overheard LaFrance’s conversation and, figuring he had the financial means, tipped him off to the real estate opportunity.

To many, the Longhorn’s location at an industrial crossroads just south of downtown would not seem lucrative, but LaFrance knew of nearby redevelopment projects like the South Side Complex, the proposed Texas Bullet Train, and the beautification of the Trinity River. So he approached Ramirez, who also owned the adjacent Mexican restaurant, Raul’s Corral.

Since acquiring the property in 1996, Ramirez had, according to LaFrance, hosted rodeos, quinceañeras, and a mercado, yet in 2001, Ramirez put the Longhorn (and its 4.5 acres) up for sale with an asking price of $3.95 million, according to the Dallas Morning News. This past April, sixteen years and several offers later, Ramirez struck a deal with LaFrance for an undisclosed amount, resisting other offers from developers who wanted to scrap the place for mixed-use. LaFrance says his offer prevailed in part because he wasn’t going to demolish the place, at least initially. (Ramirez was not available for comment.)

LaFrance envisioned sitting on the property and letting it mature in value. In time, it might make a nice location for a fancy new hotel. Throughout the negotiation process with Ramirez, though, LaFrance grew enlightened about the legacy of the Longhorn Ballroom, aided by one of his two sons, Jayson, a web designer, and his daughter, Amber, a publicist. They argued that the Longhorn needed to be saved, not destroyed. So LaFrance decided to make a family business out of it. “I have a passion for music and I have a passion for history, and it’d be a shame for this place to be bulldozed over and replaced by apartments that could be put anywhere else,” he said.

Piecing together the story of the Longhorn Ballroom has become a preoccupation of the LaFrances. Their main source has been Doug Groom, whose deceased father, Dewey, ran the place from ’58 to ’86. Doug now lives in a motorhome in Ruidoso, New Mexico, where every day he plays golf, strums his guitar, and drinks wine. Back in the day, he worked with his dad and booked many of the acts, including the Sex Pistols. Through a third party, he reserved their date a year in advance without being told who was going to play, and even when he was informed who to put on the marquee, he hadn’t a clue who they were. Upon seeing television footage of the unruly foursome after landing in New York for their tour, his dad asked him, “What in the fuck did you do?”

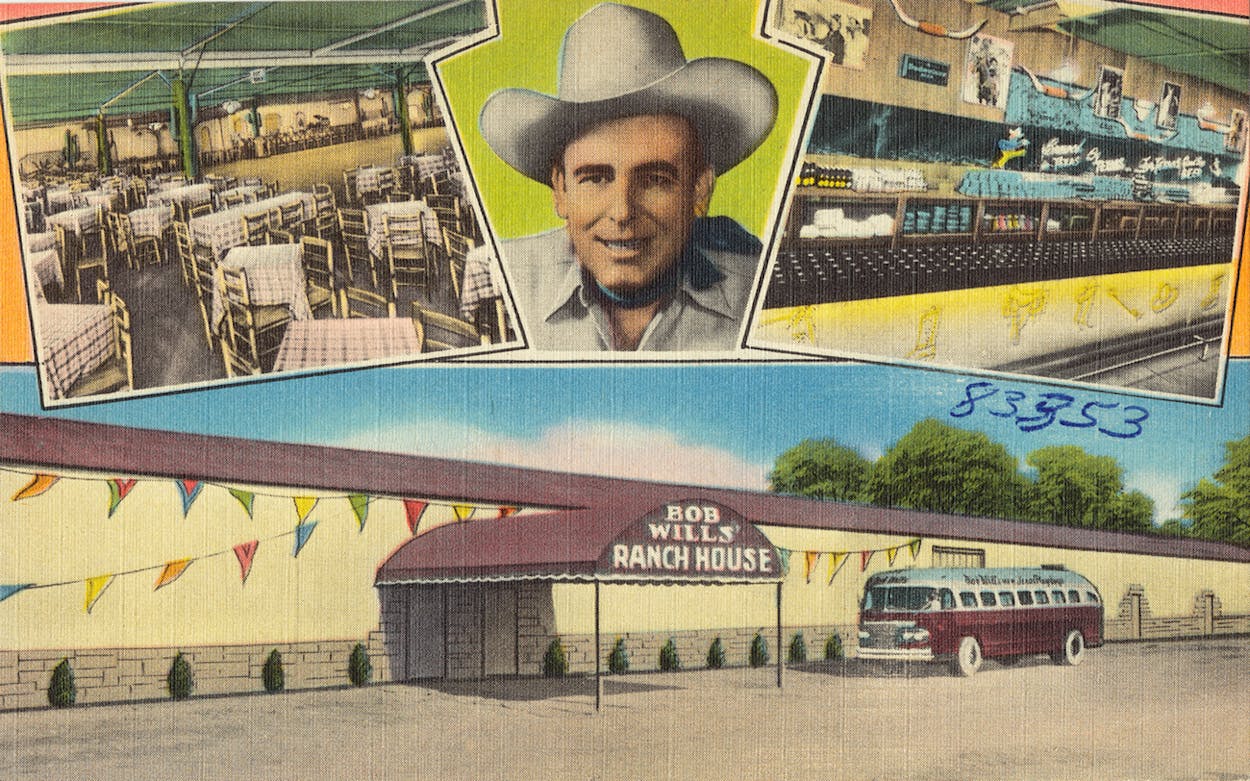

According to Doug, O.L. Nelms, a Dallas real estate tycoon, built the Longhorn Ballroom, originally named the Bob Wills Ranch House, for Wills and His Texas Playboys. Mismanagement led to a knock on the door from the IRS roughly a year later, and Wills was forced to close the Ranch House. He reportedly sold his songs, including his signature, “San Antonio Rose,” to pay off the debt.

In 1952, Jack Ruby, a decade away from murdering Lee Harvey Oswald, signed a lease with Nelms to take over the Ranch House. If memory serves Doug correctly, Ruby changed the name of the place to Sadie Hawkins. At the time, Dewey had a band called the Texas Longhorns, who were a regional hit, and Ruby invited them to be the house band. “We’ll take the bar and you can take the door,” Doug said Ruby told Dewey. “Let’s open this place up and see if we can make some money.”

Once again, this arrangement ended almost as quickly as it began. Within months, Ruby had a self-described “mental breakdown,” according to the Warren Commission, and bailed on Sadie Hawkins. In 1958, Nelms convinced Dewey to take over management of the place, by then called Longhorn Ranch. A wall divided the inside into two distinct performance spaces. On one side, the country tradition prevailed, with Dewey Groom and the Texas Longhorns playing regularly in addition to touring acts. On the other side was the Guthrie Club, where rockers and bluesmen like Jerry Lee Lewis, John Lee Hooker, and Jimmy Reed poured sweat.

In 1967, Dewey bought the property outright. He renamed it Longhorn Ballroom, prompted by the influx of people who, under the name Longhorn Ranch, were calling to inquire about purchasing cattle. He also tore down the wall and went full-on country six nights a week. The Texas Longhorns continued to play up to five of those nights, with special performers on the sixth, including the likes of Tammy Wynette, Ray Price, and Willie Nelson.

“We seated 2,000, 2,500 people,” Doug said. “If you go back to the ’50s, ’60s, even the ’70s, country music wasn’t like it is now. I mean, there were only five or six places in the United States that could seat that many people. There wasn’t no 10,000-seat halls. Willie Nelson wouldn’t draw flies. We lost money on Willie Nelson in the ’60s and paid him $300.”

On the seventh night, the Longhorn Ballroom rented out the space to black entertainers, and among the high-profile performers were B.B. King, Ray Charles, and Nat King Cole. “The two people that hold the record for attendance at the Longhorn are both black,” Doug said. “One of them is Al Green. The other was Charley Pride.”

In April 1986, Dewey sold the Longhorn Ballroom to Ira Zack, a local club owner, who hired Jeffrey Liles, an upstart booker, to fill the calendar. Incidentally, Liles, the current artistic director of Dallas’s historic Kessler Theater, attended the Sex Pistols show eight years prior, when he was a student at Richardson High School. “It wasn’t an amazing performance, but it was an amazing spectacle,” he said. “It was cool to see the culture clash.”

Liles drastically shifted the focus towards contemporary acts like Red Hot Chili Peppers, Big Audio Dynamite, and Motorhead, but he wasn’t on the job long. One night in October, Zack went home and committed suicide. The Longhorn stayed open for a couple more months, fulfilling its dates, and then it went out of business. Again. Fred Alford, of Alford Refrigeration, would next come into possession of the place, renting it out for occasional shows, including the disastrous 2 Live Crew gig, but eventually Ramirez took over.

The Longhorn has been a shell of itself for the past two decades. To get it back on people’s radar, LaFrance needed promotional and financial support. As he worked his deal with Ramirez, he turned to the City of Dallas for help. “You have conventioneers who are coming to Dallas and they want the Texas experience, and they’ll bus them all the way over to Billy Bob’s, in Fort Worth,” he said. “It’s like, why is Dallas losing that revenue to Fort Worth? Billy Bob’s is thirty-five years old. This place is sixty-seven years old.”

That was a winning approach. The Dallas City Council awarded LaFrance a grant up to $500,000 to support his redevelopment efforts, with the caveat that he invests at least $1.4 million and restore both the Longhorn Ballroom sign, designated a landmark in 1984, as well as the building’s façade. “The project represents a catalyst opportunity for longer-term revitalization of the area known as Cedars West,” J. Hammond Perot, assistant director in the Office of Economic Development, wrote in an email.

On a Saturday morning over Memorial Day weekend, I visited the Longhorn Ballroom with Jayson and Amber LaFrance. Jayson, 32, sported a trim beard and a cabbie hat. Amber, 29, wore a Motley Crue t-shirt and cut-off jean shorts. They showed off half-completed murals of the Longhorn’s forefathers, Bob Wills and Dewey Groom, painted by local artist Stylle Read. They then rattled off a laundry list of ideas. In addition to resurrecting the ballroom itself, they talked of building a creative hub with artist studios, a gallery, and a band rehearsal space. They’d like to resuscitate the defunct recording studio in Raul’s Corral. They also plan to create a gathering space on the banks of the Trinity River and fill it with shipping containers that would host food and retail vendors during festivals and movie screenings.

“It’ll be cool because it will be a mix of, like, celebrating the old but also, like, bringing in an entire new generation of people that are my age that have never been here—or heard of it,” Amber said.

Returning from the far end of the property, where a cluster of stars bearing the names of past performers are set into the ground like the Hollywood Walk of Fame, we noticed that a red SUV had scooted into the parking lot. Out stepped Ricky McGuire, whose mom, Gladys, was Dewey’s sister. McGuire happened to be in the area for a family reunion and stopped by because he heard that someone had purchased the place. We invited him along, and he proceeded to show us old pictures of his family and the Longhorn.

While inside, Jayson and Amber stood in front of a neon sign depicting a giant set of steer horns, perhaps recognizable to fans of Aerosmith, who shot the video for their 1989 song, “What It Takes,” in the Longhorn. They talked about reprinting concert posters from some of the Longhorn’s most famous gigs, and trying to put out a vinyl recording of one of Merle Haggard’s shows there. They also pointed to a safe abandoned by Jack Ruby and talked about hosting a safe-opening party.

Three months later, on September 9, the Longhorn Ballroom opened its doors for the first time since the LaFrances took over. The occasion was a charity event. Dallas City Councilman Adam Medrano was there to flip the switch on the marquee, and beneath it sat a refurbished version of the massive longhorn sculpture that gives the place its name. Onstage, country licks were supplied by a number of musicians, including Leon Rausch, who played with Wills in the Texas Playboys. Though the Longhorn will now operate primarily as an event space, it had still come full circle. (Texas Monthly will host an event there on November 11.)

“I didn’t realize how big of a deal this was for Dallas and the people of Dallas that have experienced this place,” Jay LaFrance said. “I once was talking to somebody on the phone and the receptionist says, ‘Hey, I just want to thank you for buying the Longhorn and restoring that. I used to go there all the time.’ Or my contractor that was clearing the brush and trees behind the Longhorn, he goes, ‘My mom and dad met there and they’ve been married sixty-five years since.’ I constantly hear these stories.”

Experience the newly restored Longhorn Ballroom for yourself at Texas Monthly‘s The Edge of Texas.