It’s been a bumpy road to SXSW Interactive’s first Online Harassment Summit. In October, SXSW kicked a digital hornet’s nest when they canceled two gaming panels citing security concerns. Level Up, a panel on building safer gaming communities, and SavePoint, a panel backed by Gamergate—a group which, depending on who you ask, either advocates for ethical gaming journalism or targets women in gaming communities— were both canceled, a move that seemed to be separating the two conflicting groups. It quickly became evident to SXSW that they’d made a mistake: the cancellations resulted in outrage and media outlets threatening to withdraw from the conference. In canceling the two panels, they’d demonstrated a poor understanding of how online and offline harassment works, and what it seeks to achieve, which is the silencing of voices of marginalized people—mostly women. To remedy their mistake, SXSW Interactive not only reinstated the two sessions, but they began reaching out to more speakers to organize a day-long summit about harassment that would be available to the public through live-streaming. That all came to fruition on March 12.

Probably appropriate for something born from controversy, the summit wasn’t without its hiccups. The early planning stages included SavePoint, though the panel was about gaming and not actually about harassment. As of press time, SXSW has yet to respond to questions concerning the Online Harassment Summit, so it’s unclear how the Interactive coordinators expected SavePoint to exist under the same “big tent” discussion about online harassment with members of the Level Up session and some of the other speakers they invited. Especially when some of the speakers such as Caroline Sinders, design researcher at IBM Watson, and Brianna Wu, head of development at Giant Spacekat, have both written about the harassment they’ve received from Gamergate. It seems that SXSW eventually caught on to the error, though. In November, along with an announcement of new speakers for the summit, there was also a small update that noted that the SavePoint session had been moved to Tuesday, March 15.

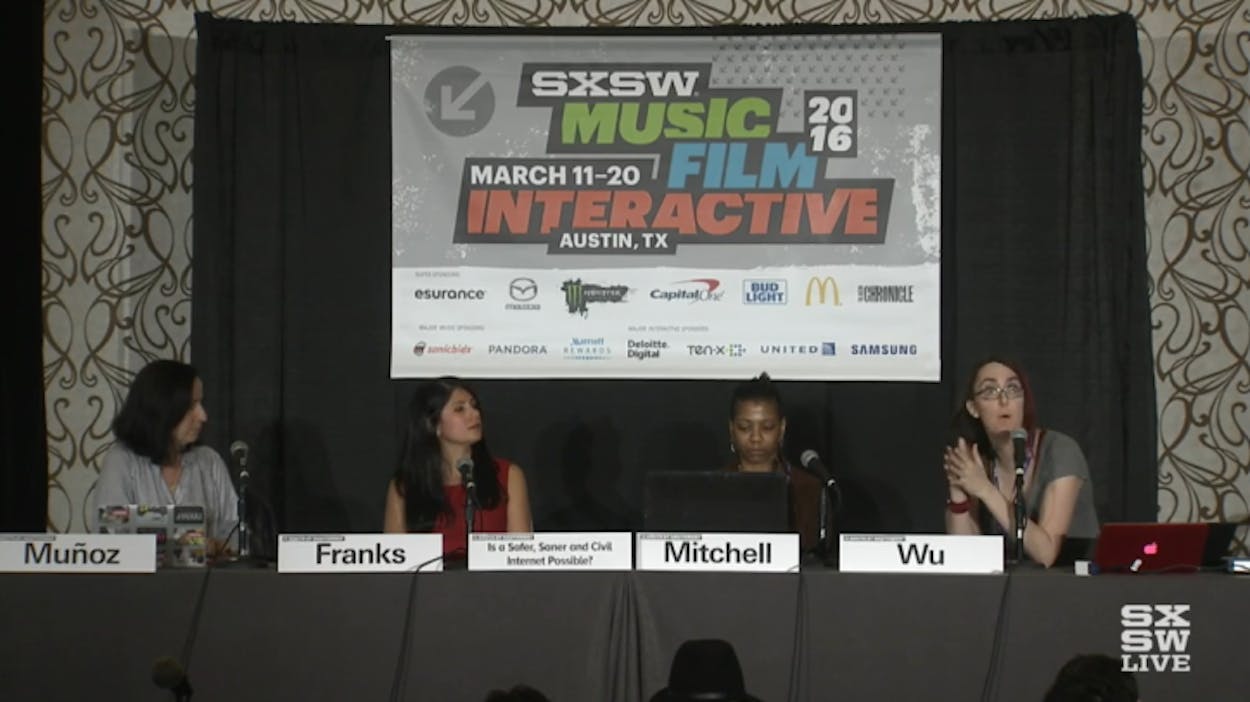

On Tuesday, SavePoint is still taking place in the same location as the rest of the Online Harassment Summit session on Saturday—in the Hyatt Regency Austin, which is south of the Colorado River and noticeably removed from the majority of the SXSW sessions downtown. Although the panels that initially ignited the controversy were centered on gaming, the session and panelists covered a wide range of topics and industries affected by harassment, from gaming to social media websites to journalism to government. One of the opening panels, “Is A Safer, Saner and Civil Internet Possible?,” attempted to gain understanding the nature of harassment in all its forms, before exploring how various industries fail to properly address it. “Tech and the United Front Against Online Hate” approached the topic from the angle of what’s currently being done to address harassment. And “Level Up: Overcoming Harassment in Games,” explored hypothetical solutions for creating games and online communities that are safe.

Although the points of the discussions varied greatly, there were common threads between the sessions. One major theme was that there is very little understanding of what online harassment can look like across spectrums of identities and industries, which greatly interferes with the ability to properly address it. How do you fix a problem that you don’t fully understand? At the root of online harassment is the efforts to continue the silencing of voices that have traditionally gone unheard, voices that now have larger platforms to speak on the Internet.

“We’re so afraid of what women might say, we try to shut them up,” said Mary Anne Franks, a professor at the University of Miami School of Law, at the summit. It’s a reaction as old as time—men have been trying to shut women up as early as the suffrage movement and beyond—it’s just that the means to do so have changed. In addition to mobs physically attacking protestors, the Internet now has everything from comment sections filled with racial slurs and threats of rape to thousands of websites dedicated to collecting and sharing what Franks calls “non-consensual porn,” or revenge porn. What hasn’t changed, at least not soon enough, is the culture that all too often protects harassers while further marginalizing victims who can sometimes lose their jobs, get kicked out of school, and even attempt suicide.

Franks shared the story of Rehtaeh Parsons, a teenager who was raped at a party, only to suffer the further abuse of having the video of her rape posted online. Parsons later hung herself at age seventeen. In a post written by Glen Canning, Parson’s father, a line stood out to Franks that she said encapsulates this culture. In talking about his daughter’s rapists, Canning asks:

Why is it they didn’t just think they would get away with it; they knew they would get away with it.

There was also the common refrain of how online harassment often pushes women out of industries traditionally dominated by men. Not just the gaming industry, but also journalism and the tech industry as a whole. And it’s these industries that need the voices of marginalized people most, because the amount of women—and women of color—in industries and in positions of power can make a difference.

“Diversity isn’t a trend, it’s my life,” said Shireen Mitchell, the founder of Digital Sister, a nonprofit focused on serving underrepresented communities in the tech industry. Diversity’s also a necessity. According to Mitchell, since women of color deal with both gender and race-based harassment. Mitchell noted it’s important to have them “in the pipeline” to serve as “canaries in the coal mine” who can identify even more coded forms of harassment.

Perhaps the most striking thing about the summit was how SXSW Interactive’s own actions demonstrated the necessity of the topics the panelists covered. Not only did they initially respond to harassment by canceling—thus silencing—the panels of people who wanted to call attention to online harassment, but even before that they failed to take panelists’ concerns seriously. Panelists such as Sinders alerted SXSW Interactive about the content in the comments of their PanelPicker as early as August. In that email chain shared with Texas Monthly, a conference representative’s response to Sinders was, “I don’t see anything within the comments fields on PanelPicker that suggest anything overtly negative, threatening, or harassing. And our policy with proposals is that the more of a dialogue around ideas, the better.”

“I don’t know how someone can decide what’s credible for me,” said Michelle Ferrier, the founder of Troll-busters.com. If organizations with a strong online presence like SXSW struggle to grasp the levels of online harassment, it doesn’t get any easier when victims bring their problems to superiors at non-tech companies, local police departments, and state and federal government. All too often, victims are left to deal with the harassment on their own finding their own solutions. After discussing some of the harassment she’s experienced, Ferrier explained that she “had to move [her] family out of the state and get a new job” in order to feel safe.

From allowing abusive comments to exist for the sake of an open dialogue, to social media platforms that don’t consistently follow up on abuse reports, to outdated laws that require things getting physical before legal action can be taken, there’s a lot that needs to change. SXSW has taken one small, stumbling step forward in confronting the necessary changes. It’s unclear whether the Online Harassment Summit will become permanent programming for SXSW Interactive, but if it does, hopefully it takes place on the other side of the river, closer to the people who really need to hear the message.