Standing here in 2015, outside the last hoodoo pharmacy in Texas, you’ll find little more than acres and acres of weed-choked and garbage-strewn vacant lots in the shadow of Houston’s skyscrapers. It now seems unfathomable that Stanley Drug Company’s stretch of Lyons Avenue, between Hill Street and Jensen Drive in the Fifth Ward, was once one of the busiest commercial districts in all of Texas.

Back in the 1950s, it was hoppin’—arguably the most vital of Houston’s three scattered African-American downtowns, eclipsing both Dowling Street in Third Ward to the south and West Dallas Street in the Fourth to the west. As old Houston Press columnist Sig Byrd wrote around 1950, you could eat at the Boogie Children Cafe or La Joya Spanish Dining Room; eat, sleep and imbibe at Seahag Jackson’s Number One Hotel, Liquor Store and Lunchroom; get yourself decked out the Harlem Tonsorial and Shoeshine Parlor; and grab field game to go—raccoons, opossums and rabbits—at Rochelle’s Meat Market.

There were the Roxy and the De Luxe movie houses, and nightspots like Club Matinee and Club 44: the stomping grounds of many of the most famed musicians the Nickel ever produced: sax greats like Arnett Cobb and Illinois Jacquet, piano man Ivory Joe Hunter, and guitarists Gatemouth Brown and Goree Carter, a man I believe invented rock and roll in 1949. One-man-band and blues poet Weldon “Juke Boy” Bonner was another denizen of this strip, and often as not, he sang of its too-frequent shootings, cuttings and beatings. In one song, Bonner warned that coming here meant “you’re liable to get your head bashed in if you try to break a twenty after dark.” In another he warned his listeners to “Stay Off Lyons Avenue” if they wanted to live, because “if you go there green, somewhere around Jensen is that last place you’ll be seen.”

Despite its commercial success, the strip had long been rough-and-tumble. Byrd reported that five bullet-riddled bodies were found on the strip on a single weekend in the 1940s, thereby earning the area the nickname “Pearl Harbor, the Times Square of the Bloody Fifth.” It would still be known by that name, and others, in 1976, when Texas Representative Mickey Leland took Texas Monthly’s Richard West on a tour. Seated behind the wheel of his long yellow T-Bird with a vanity plate reading “SO BAD,” the flamboyant, dashiki-wearing Leland called Lyons Avenue “the Bucket of Blood District” and pointed out that in the not-too-distant past, it had been the scene of the most murders per capita of any place in America.

For a time, death was an everyday presence on these corners. Byrd reminisced about I.S. Lewis, a legendary Lyons Avenue undertaker. The better to drive home the importance of purchasing burial insurance, Lewis was known to deck out a pauper’s cadaver in a dress suit, place a tin cup in its stiff fingers, and prop it up in a chair outside his front door.

It’s not surprising, then, that many on Lyons Avenue sought protection from a higher power. For some, what they got in the pews at nearby Pleasant Grove Missionary Baptist Church or Our Mother of Mercy Catholic Church in nearby Frenchtown was not enough. To get that extra edge, you needed the folk magic practice hoodoo, and each neighborhood was home to its sage practitioners. These were the people who could set you up with non-pulpit-approved prescriptions of powders and potions, candles and baths, chants and prayers, to fix whatever or whoever was ailing you, from constipation and erectile dysfunction to cheating lovers or miserly bosses.

And believe it or not, the hoodoo tradition still lives on in what used to be Pearl Harbor. In fact, after integration spurred an exodus to far-flung parts of town, and after the construction of Interstate 10 and Highway 59 crucified the neighborhood in the sixties and seventies, turning the theaters, clubs, shops, houses, gambling spots, and hot-link parlors to dust, now all that remains of this brawling, once thriving city-within-a-city is Stanley Drug.

Once common in the big cities of the Deep South, places like Stanley Drug often started as regular compounding pharmacies but evolved over time, by popular demand, into purveyors of the sorts of candles, incenses, herbs and holy oils sacred to America’s hoodoo tradition.

Stanley’s general manager Stephanie May says hoodoo is everywhere in East Texas and the South, once you learn how to spot it. A native of the south Arkansas-north Louisiana borderlands, May says it was all around her growing up. But until she inherited Stanley from her uncle some years back, she didn’t recognize it.

“Friends and family had always practiced this but I just didn’t know,” she says. “Keeping a bowl of lemons by your front door because it protects you is a hoodoo thing. The desire to use ammonia to clean everything. That’s a very hoodoo thing. Those bottle trees? Those are to capture evil spirits. And if you drive through Mississippi now you’ll see old TV tubes sitting out in the yard or up in trees. Same thing—to capture evil spirits. Blue around windows and doors? That’s for protection. It’s all around you and you just don’t see it. People are dabbling and you just don’t know until you learn about it.” (Some even believe that most Texan of holiday rituals—the consumption of black-eyed peas, greens and cornbread on New Year’s Day for good luck and prosperity—is a hoodoo ritual.

Back in Sig Byrd’s day, Houston’s “main hoo-doo supply house” was Bichon’s Drug Store in Milam Street’s rough-and-rowdy Catfish Reef mini-district. The wares were not nearly as commonplace as lemons in a bowl:

Here citizens who dabble in mojo and hoodoo can buy such innocuous items as dragon-blood sticks, for luck; wonder-of-the-world root, for locating treasures; and sweet mama shakeup, to encourage romance. If you need something a little stronger, you can get oil of bendover, Adam and Eve root, spirit oil, Chinese business powder, black-cat perfume, five finger grass, lodestones, steel filings, easy-life powder, controlling oil, anger powder, mad water, high-john-the-conqueror root, and getaway powder.

Bichon’s is long gone, as is the Catfish Reef district—few even remember the name today, and the block is given over to parking garages. Now only a few such shops remain throughout the country—notably Miller’s Rexall in downtown Atlanta and F&F in New Orleans Treme section, but old blues lyrics from Texas artists suggest its one-time importance in African-American Texan culture.

In Blind Lemon Jefferson’s “Low Down Mojo Blues,” he sings: “My rider’s got a mojo, and she won’t let me see; Every time I start to lovin’, she ease that thing on me.” Lightnin’ Hopkins famously declared in song that he was “goin’ to Louisiana and get me a mojo hand; I’m gonna fix my woman so she can’t have no other man.” And from right here in Fifth Ward, lap-steel guitarist Harding “Papa Hop” Wilson once lamented, in a song that wound up helping Albert Collins, Johnny Copeland and Robert Cray win a Grammy many years later: “I believe my baby got a black cat bone; Seems like everything I do, seem like I do it wrong.”

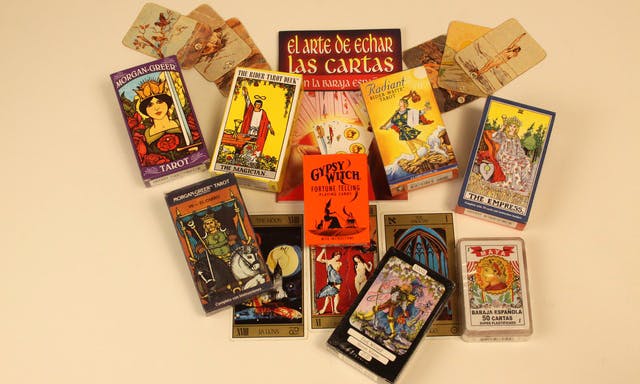

You don’t hear MCs rapping about mojo hands anymore. I’d assumed hoodoo was just another cool dead relic of the Old Weird America, but here it is alive and well at Stanley Drug, a gunmetal-gray corrugated warehouse-looking building behind a tall chainlink fence. It doesn’t look like much from the outside, and once inside, to the non-practitioner of hoodoo, your first impression of the small shop floor is disappointing. Three sides of the room are stacked high with shelves of colorful candles or bottles of oils and waters, or jars of powders and dried roots. If you’ve been to a Mexican yerberia or a Caribbean botanica, Stanley’s display area looks similar at first glance, and the showroom is tiny compared to the building’s footprint.

It’s when May takes you behind the scenes that you see how the place has survived the demise of all else around it. You won’t find aspirin, Alka-Seltzer or allergy pills at Stanley Drug today, though they did once sell all that and fill prescriptions too. Open since 1938, and now moved to their third location in the immediate vicinity, Stanley was once just another American pharmacy. That began to change as more and more of customers came in clutching prescriptions not from MDs, but from the Dualehs of the neighborhood.

In the hoodoo vernacular, such people were called “root workers,” or just “workers.” “[Most] had names like ‘Mother Miller,’ and I always likened them to matchmakers in the Jewish community,” May says. “They did more than matchmake, they helped you resolve problems. So you would go see Mother Miller and tell her your problem and she would write you a prescription, and she would say ‘You need to go to Stanley Drug and pick up [these things].’”

Since integration, many African-American folk traditions—including root workers—have died out. Now it’s May or her staffers who consult with customers and fill the prescription, drawing much of their custom from family tradition and word of mouth. “Now it’s more about ‘Oh, my mama went there,’ or ‘My grandmother went there,’” May says. She estimates her customers are about 40 percent African-American, 40 percent Hispanic, and the remainder Caucasian, many of them New Age seekers or practitioners of “magick.”

One reason the showroom floor is tiny relative to the building’s size is that so much of it is given over to inventory. The average Stanley customer is not a browser—they have a specific problem for which there is a specific solution, and they want to get cracking on it right away. And so a large back room is given over to shelves stacked with colorful jars of oil, fragrances, and powders, all of which exist in some literature somewhere in association with a particular power.

They have names such as Lucky Mojo, John the Conqueror, Crucible of Courage, Master Key, and Love Me. There’s also a couple of Rolodexes full of yellowing index cards bearing handwritten recipes for various hoodoo spells and potions.

“The breadth of your inventory has to be spectacular, because if someone comes in today and needs something, they need it today,” May says. “This place is not like Walmart. Nobody comes in here to shop.”

Between the storage area and a card reading room is the altar room, where hundreds of flickering candles stand atop handwritten prayer petitions, each one representing the fervent wish of one of May’s customers. You’ll also find a Day of the Dead oferta stacked with cakes, pies, fresh fruits and bottles of booze. Nearby is another complicated shrine, albeit to a living person: a pink washtub containing a pair of worn-looking jeans and a sweat-stained work shirt, topped by the photograph of a smiling young man, the whole thing ringed by candles.

“The closer something is to you personally, the more power it has,” May explains. “The least powerful is a photograph, and then clothing is next, and it works its way up from there.” (To hair, bodily fluids, and so on. Some experts believe that the Blind Lemon Jefferson lyric “I can’t drink coffee and the woman won’t make no tea / I believe to my soul my woman gonna hoodoo me” refers to his fear that his woman might be altering his coffee with menstrual blood.) “Anything you can get adds more power to what you are trying to accomplish, so somebody is trying to effect this person somehow. What they are trying to do, I don’t know.”

The candles and shrines live on Stanley’s premises for a reason: the people who bought them don’t want the people they are praying for or attempting to control to know. Like Jefferson sang, Stanley Drug is less cash-and-carry than it is cash-and-bury. That’s why the store’s door—and much of the parking area, as well—is situated at the rear of the windowless building. Few of her customers want anyone else to know they shop there. May doesn’t send out email blasts. “Stanley Drug” does not appear on credit card statements. Few people check in on Facebook.

“You know how Baptists won’t speak when they run into each other at the liquor store? It’s like that here,” she says.

A great many of her secretive customers want to keep their supernatural advantage over their significant others under wraps. It doesn’t always work. “So many of the men who are associated with the women who come in here are well aware of that, and they won’t eat food at their girlfriend’s house. I have employees that won’t eat food made by certain customers, or certain other employees.”

And if those on the receiving end of those prayers and incantations do find out, their hoodoo counterattacks can be chilling. May has found everything from mutilated cats, rabbits, and birds to candles carved with occult symbols in her parking lot, or her doorway sprinkled with gris-gris herbs designed to bring evil to her shop.

“You know how Baptists won’t speak when they run into each other at the liquor store? It’s like that here,” she says.

“We believe some are trying to ‘work’ on a specific customer that may be a regular or have candles burning in our altar room,” she explains. “Let’s just say we sweep the parking lot with regularity.”

Truly the work of the Devil. Sometimes Stanley Drug is visited by men and women of God, and not for the casting out of sin, the reason you might expect.

“We get a few preachers,” May says, stifling a smile. “They come in and buy candles to increase their collections.”

Now is that not the most Southern thing you’ve ever heard? A preacherman resorting to hoodoo?

By now the tour is over and we’re seated in May’s office. There’s a pistol-grip shotgun propped in the corner, a desk with computer, a landline that never stops purring, and a groaning bookcase. Off in the distance locomotives moan low and long every few minutes, pulling mile-long freight trains across this heavily industrial section of Houston to and from the nearby Ship Channel or the faraway Mexican border.

May explains that American hoodoo is not Haitian voodoo. Unlike voodoo, hoodoo is not a true religion with dogma, gods, and a priesthood, but instead a set of folk magic practices that can vary from practitioner to practitioner. Although both have roots in Africa, voodoo is heavily influenced by French Catholicism, hoodoo more by both the Old Testament and American Indian botanical lore.

Contrary to popular belief, voodoo is no longer practiced in New Orleans, at least not in its pure Haitian form. Much of what passes for voodoo there is what hoodoo expert Catherine Yronwode calls a faux-religion, a tourist attraction. On the other hand, hoodoo does live on in parts of New Orleans, and some practitioners just call it voodoo.

“Hoodoo is a group of magical practices, all based on Christianity,” May explains. “Everything we do is what you would call white magic. We use the Psalms, we use the Bible.”

But some customers would prefer a darker variety of hoodoo. May tries to dissuade them. “People come in here and want to hurt somebody, to affect somebody, and we just tell ‘em, ‘If you wanna do it, go right ahead, but we do not recommend it, and you are gonna spend a ton of money.’ And anytime someone comes in and wants to change someone else, my standard response is ‘When is the last time you changed yourself? When is the last time you broke a habit? Stopped doing something bad or started doing something that was healthy? And as hard as that was, how hard is it gonna be, to affect someone else?’”

Counseling, intuition and plain conversation play as much a role as the dispensing herbs, invoking Psalms and lighting candles, May says. Her sales staff doubles as a counselors, she says, and she won’t let any of them work more than five days in a row. “All they hear all day long are people’s problems,” she says. “Some of them are kooky, some of them are superficial, some of them are downright horrifying. They not only help them select their candles and tell them which Psalms to repeat and which prayer and whatever, they just let people talk.”

That’s vital for her clientele. Many of them don’t have anybody else to go to.

“They live in a real small world,” she says. “Maybe they are Hispanic and they don’t have a very good command of English, they’re here with their families, they’ve only been in this country a couple of years, they don’t have many friends, they’d don’t have a network.”

Last year a young woman came in with her infant child. She told May she had just fled her abusive husband, a member of the Zetas who had started dipping into his own inventory and become violent.

“The Zetas of course told him he had to stop,” May details. “And he told them ‘It’s because my wife left and I’m distraught. I wouldn’t be this way if she were here.’ So they called her and said ‘Come back or we’re gonna kill your husband. He has a habit and you have to go back.’ So she came here asking us what candle she could burn, and we took her aside and said ‘You can’t go back. You have to understand. They are going to kill you, they are going to kill your child, and they are not going to do it in a nice way. You must leave, right now. Don’t tell us where you are going. Do not call your mother, do not call anybody. Leave. Houston. Texas. Don’t look back.’ And she called several months later and she’d done exactly what we’d asked her today, and she was okay, she was safe.”

May believes that the supernatural can only go so far, that sometimes only practical, real-world advice can suffice. She believes that the vast majority of her customers have what she calls “superficial” problems: love woes or minor job issues, a child with a looming misdemeanor court case and the like.

And then came the Great Recession of 2008. “Then it became ‘I’m gonna lose my house,’ ‘I can’t afford to buy food.’ One of the reasons we are still so popular, multi-generational, is we won’t take your money, we won’t say ‘Give me $1,500 and I’ll fix your problems.’ That’s a real scam. There are people here who think of this as fast money and that’s what they do. So we began to send people to agencies, that they needed to go talk to people like that rather than us. And now we’re back to the superficial right now. It was really scary for a while, seeing those people come through the door.”

Stephanie May has two degrees. In past lives, she’s worked in the restaurant business and as an oil and gas executive. A self-described “gun-totin’ liberal,” she’s also a Southern aristocrat—her ancestors owned thousands of acres of Arkansas plantation lands (and when not in Houston, she’s farming some of that same land today). All of that would make it seem unlikely that she was a true believer in hoodoo, and May says a TV reporter once asked her if she believed in the magic she was selling.

“I told her I believed in positive visualization,” she says. “If it takes lighting some incense, burning a candle, saying a prayer, wherever you find that positive energy, then yeah, I believe in it. We stopped counting after more than ten of our customers had won the lottery. We don’t sell Lotto tickets, but there’s not a convenience store in town that could tell you that. Now is it because all my customers play the lottery? I don’t know.”

The same principles May applies on her holistic farm in Arkansas also are at play in hoodoo. “It’s like the butterfly effect—everything you do affects the whole. The way your raise animals on the farm, your business, the way you live your life, you have to consider that your overarching goal is maybe to be happy and out of debt. Everything you do needs to march toward that goal. It’s the same way with the people who buy candles, herbs and incense here: they are attempting to achieve that goal, and it’s one more step in that direction.”

The successful practice of hoodoo is more about changing your path than merely performing a ritual or making a sacrifice, May believes. It’s also about positive thinking. “If you change yourself, amazingly everyone else around you changes too,” May says. “You change your attitude, the way you look at life, suddenly, the world changes. It’s so much easier to try to change yourself. But you wanna try to change someone else? I’ll happily take your money, but don’t expect it to be easy.”

She cites one timely example. A popular New Year’s hoodoo ritual: “Bayberry kit burned to the socket brings love to your life and gold to your pocket,” she recites. “The kit has the Psalm you read and a bayberry bubble bath and there’s a whole ritual you perform on New Year’s Eve. There’s a candle you burn every day for seven days to bring positive influences into your life. If you believe your life’s gonna be better this year, your life is gonna be better this year. If I spend the first week of the year thinking positive thoughts, it’s gonna help. And the fact that your house now smells awesome doesn’t hurt.”

By now May and I are out in the parking lot, taking in the sad surroundings. She tells me that a few weeks prior to my visit, she saw two bedraggled men across the street digging holes in the vacant lot with shovels. Worried that they might hit an underground power line and fry themselves to a crisp, she called the police, who shooed the men away. The cops told May the men were digging for treasure, literally. One of the men said that family legend had it that his grandfather—a storekeeper back in Pearl Harbor’s heyday—had buried a bag of cash behind his store.

Legendary buried treasure is almost all that remains of Lyons, and the root workers are also dead and gone. And yet Stanley Drug lives on, even though its clientele now is spread far and wide, from Fort Bend County to Cypress to Humble, a link to the old days and a beacon of hope in a world full of trouble and a city where the past tends not to exist.