Measured solely by the bottom line, vast oil discoveries are always good news for Texas. The recent fracking boom supercharged the Texas economy, especially in oil and gas hubs like Midland-Odessa, Houston, and—thanks to its proximity to Eagle Ford—San Antonio. All of those regions recently enjoyed construction booms, the additions of tens of thousands of good jobs, rising property values, and boosted tax revenues.

And up until now, most (but certainly not all) of the land from which these fuels has been extracted is among the least glamorous locales in the state: the rugged, mesquite and prickly pear scrub southwest of San Antonio—beloved only by ranchers and deer hunters—and the Permian Basin, which, if not for oil, would be the Lone Star State’s Empty Quarter.

So though we have heard lots of concern over fracking’s effect on air and water quality, its apparent link to earthquakes, and the rising traffic and Friday night crime every boomtown attracts, we’ve heard relatively little about what a mammoth oil play could do to the physical appearance on the state. Put another way, fracking has had little impact on Texas tourism or sightseeing.

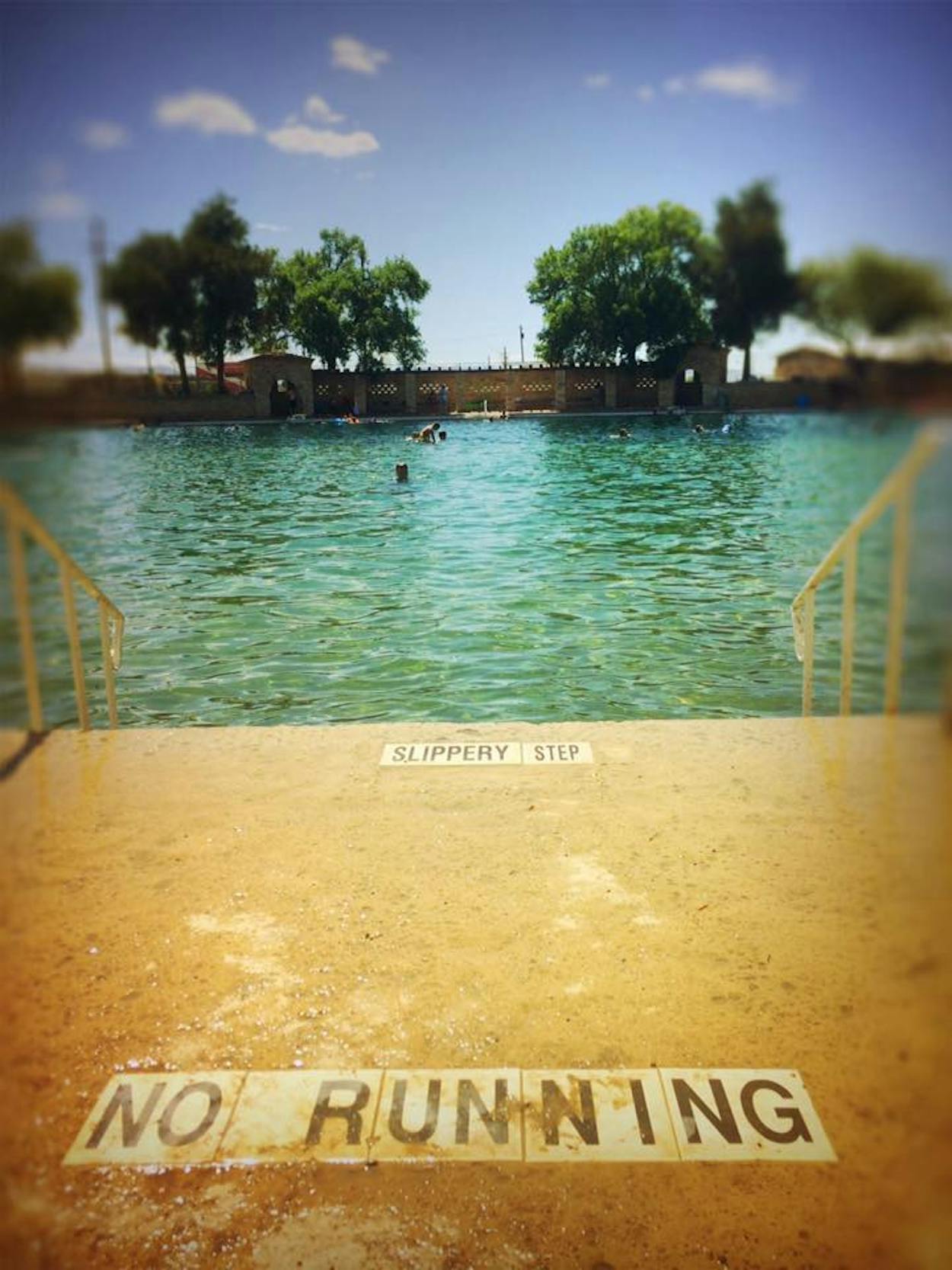

That could all change with this latest gargantuan find: Houston-based Apache Oil’s Alpine High Field, which is mostly in western Reeves County, could hold as many as three billion barrels of oil and 75 trillion feet of natural gas (worth up to $80 billion), all of which would take up to 3,000 wells to extract. That vigorous extraction will be taking place very near one of the state’s most beautiful and even mystical spots: the chilly, Depression Era swimming pool built atop San Solomon Springs in Balmorhea State Park.

Archaeologists believe that paleo-Indians such as the Clovis Mammoth Hunters camped near the lush oasis, and Mescalero Apaches watered their horses there millennia later. Mexican settlers channelized the spring’s 28 million gallon-per-day flow, diverting it to nourish crops they sold to the U.S. Army garrison at Fort Davis. And in the depths of the Depression, FDR’s New Deal Civilian Conservation Corps built the pool and vintage motor court that now stand on the site.

Today, its cool waters are home to two endangered species of fish, crawfish, freshwater snails, snakes and turtles, and with its maximum depth of 25 feet right there in the desert, it is one of the most surreal spots to scuba dive in North America. It’s consistently listed among the top swimming holes in the state. Last year a record 135,000 visitors took the waters there. So will it really be fracked to smithereens on the altar of the almighty dollar?

That is the fear of many locals and many, many more on social media, including an anti-drilling petition signed by just over 6,000 worried devotees of the pool, a not insignificant number, given that Reeves County is home to only about 14,000 people total.

In March, when news of Apache’s find was trickling out to the community, a few area residents sounded off at a school board meeting. “Balmorhea is a gem, we have things these other West Texas towns don’t have and it would be a shame to lose that over money that’s not going to be there forever,” said one resident, according to CBS 7.

But the beauty isn’t the only thing that could be lost. “You have a very, very sensitive ecology out there, a cavernous geology, natural fault lines in the area and these pools are home to a number of endangered species,” says Dr. Zacariah Hildenbrand of UT-Arlington’s CLEAR, the Collaborative Laboratories for Environmental Analysis and Remediation. His group studies the environmental impacts of fracking, and Hildenbrand attended that school board meeting at the invitation of Balmorhea school board member Paul Matta. “From the perspective of many Texans, this is the last place you would want to bring this highly industrious anthropogenic process, like why are you guys doing this here?”

Well, money, of course. “Clearly Apache thinks they know something that I don’t know, and that others don’t know, and that is that there is a tremendous reserve of hydrocarbons in that region,” Hildenbrand says. Balmorhea’s environs had long been considered barren of extractable oil.

Hildenbrand has been assessing “unconventional oil and gas development” for five years now and has seen its downside, notably in the Cline Shale play east of Midland. There, CLEAR found that water contamination did occur when multiple wells were clustered around their sampling sites. On the other hand, some of the contamination diminished fairly rapidly, according to the study.

There is also the danger of gas seeping into the water table. “When you are drilling for oil in these shale plays, up with it comes natural gas,” Hildenbrand says. “As has been show in the Marcellus and Barnett shales, and other shale plays all across the country.”

But Apache is saying all the right things. They promise not to drill on or under the town of Balmorhea or Balmorhea State Park. To slake the almighty thirst of all those wells, they vow to truck in brackish, non-potable water and to recycle as much of it as possible, the better to minimize harm on the oasis’s precious water table. They say the play is in its earliest stages, and that they want to engage in a dialogue with Reeves County every step of the way.

Up to now, they’ve also been listening to Hildenbrand’s group. “They’ve shown a tremendous level of interest in cooperating with [CLEAR],” he says. “We’ve dealt with a number of oil and gas companies, and Apache really appears to care about the well-being of those people and maintaining pristine environmental quality out there, and they say they want to work with a dynamic research team that will report environmental quality in an objective and unbiased manner. So, I’m hopeful that we will be able to go out there and do lots of sampling and monitoring, and hopefully we would find out there was nothing in the water and everyone’s concerns could be eased. But in the event that we do find abnormalities then we have a moral obligation to tell the people in that community right away and we would then have to implement a remediation strategy to meet the problem head-on.”

Hildenbrand goes to great lengths to describe CLEAR as honest brokers—neither environmentalist scolds nor shills for Big Oil, and he believes that Apache understands that and is willing to deal with it, come what may.

“With an issue this contentious, there will be a perception issue. You have the industry. They go out and collect samples and analyze them and find nothing,” Hildenbrand says. “Everyone is just going to say ‘That’s because you didn’t want to find anything.’ And the same goes for environmental groups. If they find problems people will say it’s in their best interest to find problems. [Apache] understands that we are neutral and unbiased. And our research is never going to change regardless of where our funding comes from. In fact, in 2011 we funded our first research project with our own personal savings.”

All of which sounds great. Apache will do its best not to ruin one of our state’s most enchanting treasures, and CLEAR, should they come up with the funding (a prospect Hildenbrand is cautiously optimistic about), would be monitoring them all along the way.

So, all will be hunky-dory, right? Whew. Maybe. And with that good-intention-paved road to hell and all, and such a complex project sprawling all around that delicate aquifer, and with so many billions flying around, would it really be casting aspersions on either Apache or CLEAR to simply cynically wonder, “What could possibly go wrong?”