Here’s a sobering demographic fact that came to national attention last year: Austin is the only large, fast-growing city whose African-American population is shrinking. Such was the troubling conclusion of a report authored by UT’s Professor Eric Tang and Postdoc Chunhui Ren, which analyzed US Census Bureau data. As The Texas Tribune wrote last year:

“It is completely outside the norm,” said Eric Tang, an author of the report, which looked at cities of at least 500,000 residents that experienced a double-digit rate of population growth from 2000 to 2010. While Dr. Tang said researchers expected to find that Austin’s African-American population was not growing at the same rate as the general population, they did not expect to find a decline. None of the other cities examined, Dr. Tang said, showed a drop.

As Austin’s population grew 20.4 percent from 2000 to 2010, its African-American population declined 5.4 percent. In contrast, the population of African-Americans increased for the Austin metropolitan region.

In other words, there were two trends identified by Dr. Tang and the Tribune: One, that the population of black residents within Austin’s city limits is shrinking, which isn’t happening in Nashville or Charlotte or Raleigh or Las Vegas, or any of the other cities that frequently top “fastest growing cities” lists. And two, that the black population of Austin’s suburbs is growing. Combine those trends, and a conclusion appears to be pretty obvious: For any number of reasons, black people in the Austin area are being pushed to live in the suburbs, while white residents are moving in to the city proper with alacrity.

That’s not news to anybody who’s, er, looked around Austin—and the racial segregation in Austin extends beyond just black and white, as Cecilia Ballí noted for Texas Monthly back in 2013. There are no shortage of white residents buying houses and moving in to historically African-American and Latino communities. But a post at highly-influential data journalism site 538.com, founded and run by electoral wizard Nate Silver, urges readers to think about “Austin” more broadly. In a piece titled “It’s Foolish To Define Austin By Its City Limits,” the data journalists explore whether Austin’s black population is really shrinking.

It’s a strange piece, in some ways—all it notes is the same thing that the reports from nearly a year ago about the study found, which is that African-American Austinites tend, these days, to actually be Round Rockers and Pflugervillains. But there are pretty huge distinctions, culturally and otherwise, between Austin and Pflugerville or Round Rock. So is it fair to act, as 538 asks us to, as though the difference between living within Austin’s city limits and its suburbs are just meaningless lines on a map?

[W]hat we think of as Austin isn’t what it used to be. The place is exploding, and depending on how we define Austin’s city limits, a simple demographic query can have many “correct” answers. Do we include suburbs or surrounding communities? Do we rely solely on the official municipal boundaries? These questions may seem wonky, but their answers often help define our conception of urban space.

Cities grow in two key ways, and when we talk about how “big” a “city” has become, or how fast it has grown, we often conflate two forms of expansion: spatial and demographic. On the one hand, the footprint of a city changes shape; year to year and decade to decade, growing municipalities annex more and more land. On the other hand, urban growth also involves a bigger and bigger batch of humanity living in and around that bulging municipality.

But the one hand does not always know what the other is doing, and when population growth outpaces geographic growth — like it has in Austin — things get messy. It becomes foolish to rely on municipal definitions of the city’s boundaries to characterize the overall urban space.

That’s an interesting thesis: but is it foolish to talk about Austin as the City of Austin when discussing demographic trends in the city, rather than talking about Austin, Elgin, Manor, Round Rock, Pflugerville, Leander, etc, etc?

Certainly there’s a risk of rendering invisible African-Americans who live in the Austin area, if not the city proper, if we focus strictly on the decline within the city limits. And that’s an impulse that should be checked. But the idea that there’s no difference between Central Austin and Elgin or Manor is a curious one, too. If it’s all basically the same, why is Austin—especially the parts of Austin where property values are growing at staggering rates, as they gentrify—so attractive to white residents, while the suburbs are suddenly becoming more attractive to black ones?

538 posits that those factors are complex—that the suburbs have an appeal because of new housing options and better schools:

It’s undeniable that East Austin has experienced rapid gentrification, but that’s not the only force at work here. Yes, the aimless yearnings of capitalism has brought condominium complexes, craft cocktails, yoga studios and yogurt shops to East Austin. But the suburbs can be appealing, too. An explosion of new suburban housing options and better school districts have enticed black Austinites to move away from the urban core.

Not everyone defecting from East Austin is a victim here. To assume that “college graduates” have “pushed” people away from the urban core is not only incorrect, it’s irresponsible. That’s a lesson that goes for nearly any city — check the narrative before you set your own.

Still, it’s worth examining that more fully: The parts of Austin where the school districts are subpar tend to be parts of Austin that black residents are leaving. Is there, perhaps, a correlation between the fact that those schools were underfunded and the fact that they were in neighborhoods that, until recently, didn’t have many white people in them?

Those schools—the ones in Austin, especially East Austin—will probably improve as the neighborhood’s demographics change. As property values go up, property taxes go up, and as property taxes go up, funding for schools increases, too.

The role money plays in this is significant. The Austin Chronicle, writing about a discussion Tang led after his report attracted so much attention, points out one fairly damning fact that suggests that not all black Austin-area residents who’ve moved to the suburbs are doing so because they’ve long dreamed of living in Pflugerville:

[P]roperty values in census tracts with African-American population losses rose an average $61,286 between 2000 and 2010; elsewhere, they’ve increased an average of only $36,889. That’s pushed many low-income black families out towards suburbs like Pflugerville, Round Rock, and Cedar Park. “It’s the suburbanization of poverty,” one older man noted. An inverted version of the original municipal makeup of 1928’s segregationist “Master Plan,” which boxed all African-Americans into a small corridor in East Austin.

Property values are climbing everywhere in Austin and the surrounding area, but the rate at which they are growing in East Austin far outpaces nearby cities like Manor and Elgin (which have seen much of the suburban growth of their African-American population). Look at the way median home prices in Austin’s 78702 zip code—the neighborhood just east of I-35, across the highway from downtown—have shifted over the past four years:

The median home price in January 2011 in East Austin was just under $125,000. By December 2014, that number was nearly $350,000. That’s down from a peak of almost $375,000! Those property values tripling in four years is presumably awesome if you own the land, want a return on your investment, and can afford your taxes—but if your income hasn’t grown at a rate to keep up with maximum allowable increases (or if you rent, and your landlord thus doesn’t qualify for a homestead exemption), you’re out of luck.

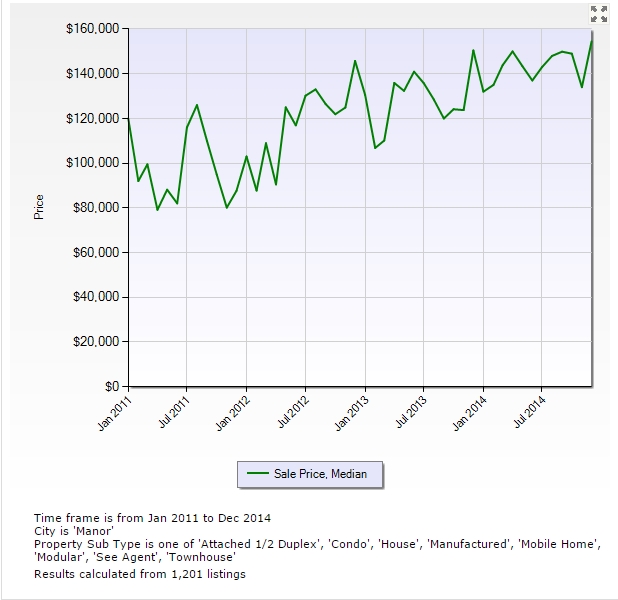

Property values are increasing all over the greater Austin area, to be certain: A rising tide does lift all boats, as they say, and more people moving to the area increases demand in Manor in the same way that it does in Austin. But it doesn’t do it at anywhere near the same rate. Take a look at the same chart, but for Manor, over the same time period:

That 30% spike in the median home prices in Manor is nothing to sneeze at, of course—if you bought a house in Manor in 2011, congratulations, you might have made $40,000!—but it’s a pretty far cry from the 300% increase in value that East Austin saw. That is to say: If you were paying rent in Manor in 2011, it probably hasn’t gone up too much when you renewed your lease three weeks ago. If you lived in an East Austin house whose property values tripled over that same time period, though—well, there’s a good chance that you live out in the suburbs now.

The piece from 538 gets the facts right, in other words, but it seems to miss the crucial context: Yes, there are more black people in the Austin area now than there were ten years ago (although the rate of growth for black folks in the greater MSA is still slower than the overall rate of growth), but the fact that that black population is growing out into the suburbs, while the white population is growing in the city, is significant. The segregation that accompanies that shift is significant, too. To suggest otherwise is to suggest that black people in the Austin area and white people in the Austin area want fundamentally different things for their families and their quality of life—and it’ll take a lot more than data journalism to convince us that that’s true.

(photo of East Austin mural circa 1978 via Flickr || graphs courtesy Julie Holden, REALTOR®)