One of the most surprising stories to emerge from this summer’s Rio Olympics was Michael Phelps’s defeat by University of Texas–Austin swimmer Joseph Schooling, a native Singaporean who out-swam arguably the most dominant athlete in Olympic history to win gold in the 100-meter butterfly.

It was the first-ever Olympic gold medal for Singapore, and the Southeastern Asian nation—which has the world’s eighth-largest GDP per capita—paid Schooling back with an award totaling one million Singapore dollars, or roughly $740,000. Not a bad haul for Schooling, who just started his junior year as a key member of UT’s swimming and diving team, fresh off of back-to-back team NCAA championships.

But the National Collegiate Athletic Association isn’t happy about the swimmer’s reward. On Thursday, NCAA President Mark Emmert said the swimmer’s huge payment may prompt the NCAA to reevaluate a relatively new policy that allows Olympic athletes to keep whatever award they get from their country’s Olympic organizations for winning medals.

In 2001, the NCAA’s member schools passed a rule that said U.S. Olympians could accept money from the U.S. Olympic Committee: usually between $10,000 and $20,000 for winning a bronze, silver, or gold medal. In 2015, the NCAA OK’d foreign athletes to accept money from their home country’s Olympic organizations too. Those exemptions fly in the face of the NCAA’s hardline commitment to “amateurism,” a vaguely defined status that the NCAA says it protects by preventing athletes from earning money or extra benefits related to their athletics outside of scholarships. The debate over whether college athletes should be paid has been raging for years now, and Schooling swam right into the middle of it.

“To be perfectly honest, it’s caused everybody to say, ‘Oh, well that’s not really what we were thinking about,'” Emmert said Thursday during a panel discussion about college athletics at the Aspen Institute, according to CBS. “So I don’t know where the members will go on that. That’s a little different than 15 grand for the silver medal for swimming for the US of A. So I think it’s going to stimulate a very interesting conversation.” Emmert said later that when the NCAA first gave the OK for Olympians to get paid, “it was such a rare occasion that somebody would be a college student and go out and win a medal. They get to do it once in their career, maybe, because it was once every four years. The members at that time hadn’t anticipated—at least this is what I’ve been told—this phenomenon of like the Singaporean kid getting paid a very large amount. I suspect they’re going to want to address this quickly because that’s a very different notion than just covering their training costs.”

Although there’s little precedent (remember, the NCAA’s international Olympic medal award exemption is less than a year old), it’s highly unlikely the NCAA will retroactively rule that Schooling must either fork over his award or forfeit his amateur status. Doing so would be a public relations nightmare. With that in mind, it’s difficult to imagine what Emmert’s end game is in expressing so much concern, other than that he’s possibly worried about the potential for Schooling’s payout to impact future litigation challenging the NCAA’s strict rules regarding pay-for-play. If the NCAA allows Schooling to earn $740,000, is it really fair for the organization to bar athletes in higher-profile sports, such as football and basketball, from profiting off of their own athletic talents?

Should the NCAA decide to do away with the Olympic payment exemption, it would end pretty much the only NCAA-sanctioned opportunity for college athletes to get paid for their athletic abilities. They already aren’t allowed to sign sponsorship deals or accept anything that even remotely resembles a performance bonus or a gift. Athletes have been found in violation of NCAA rules for everything from football players eating too much free pasta to a high school basketball recruit’s mother accepting a loan from an AAU coach to keep her family from becoming homeless. In some cases, they’ve made the athletes return what they earned, with penalties ranging widely in severity. The pasta-eaters were forced to pay $3.83 each to a charity of their choice in order to regain their eligibility, while, in 2004, the NCAA barred Colorado’s Jeremy Bloom from ever playing college football again after the Olympic skier accepted endorsement money he said he needed to fund his training for the upcoming winter games.

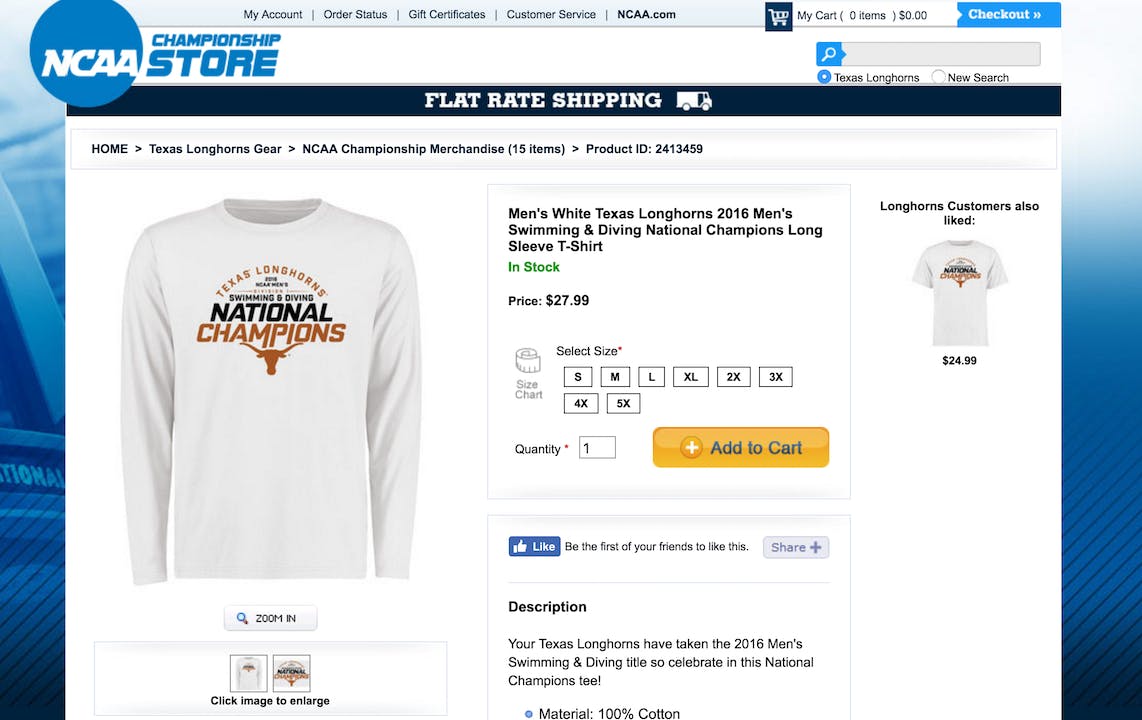

Of course, it’s not against the NCAA’s rules for the NCAA to make money off of athletes like Schooling. Emmert reportedly earns a salary of about $1.8 million a year, while the NCAA sells tee shirts commemorating UT swimming’s national championship win on its website for $27.99. But Schooling won’t see a penny of that profit.