Ector is a sleepy blink-and-you’ll-miss-it kind of place surrounded by freshly plowed fields and cattle pastures, ten miles south of the Red River, in Fannin County. The town’s one gas station doubles as its only restaurant, and in the back of it there’s a smoke-filled gaming room where patrons can earn store credit while they catch up on the latest scuttlebutt. It’s a practical town, populated by ranchers, teachers, and prison guards, and is not known for its glitz. So when a 65-foot marble and concrete fountain ringed by mermen and horses started going up in a pasture just to the west of town in January 2016, it raised eyebrows. So, too, did the shiny Bentleys and Range Rovers that would pull off Texas Highway 56 to gawk at the structure. What was going on out there, residents wondered?

Ector is a sleepy blink-and-you’ll-miss-it kind of place surrounded by freshly plowed fields and cattle pastures, ten miles south of the Red River, in Fannin County. The town’s one gas station doubles as its only restaurant, and in the back of it there’s a smoke-filled gaming room where patrons can earn store credit while they catch up on the latest scuttlebutt. It’s a practical town, populated by ranchers, teachers, and prison guards, and is not known for its glitz. So when a 65-foot marble and concrete fountain ringed by mermen and horses started going up in a pasture just to the west of town in January 2016, it raised eyebrows. So, too, did the shiny Bentleys and Range Rovers that would pull off Texas Highway 56 to gawk at the structure. What was going on out there, residents wondered?

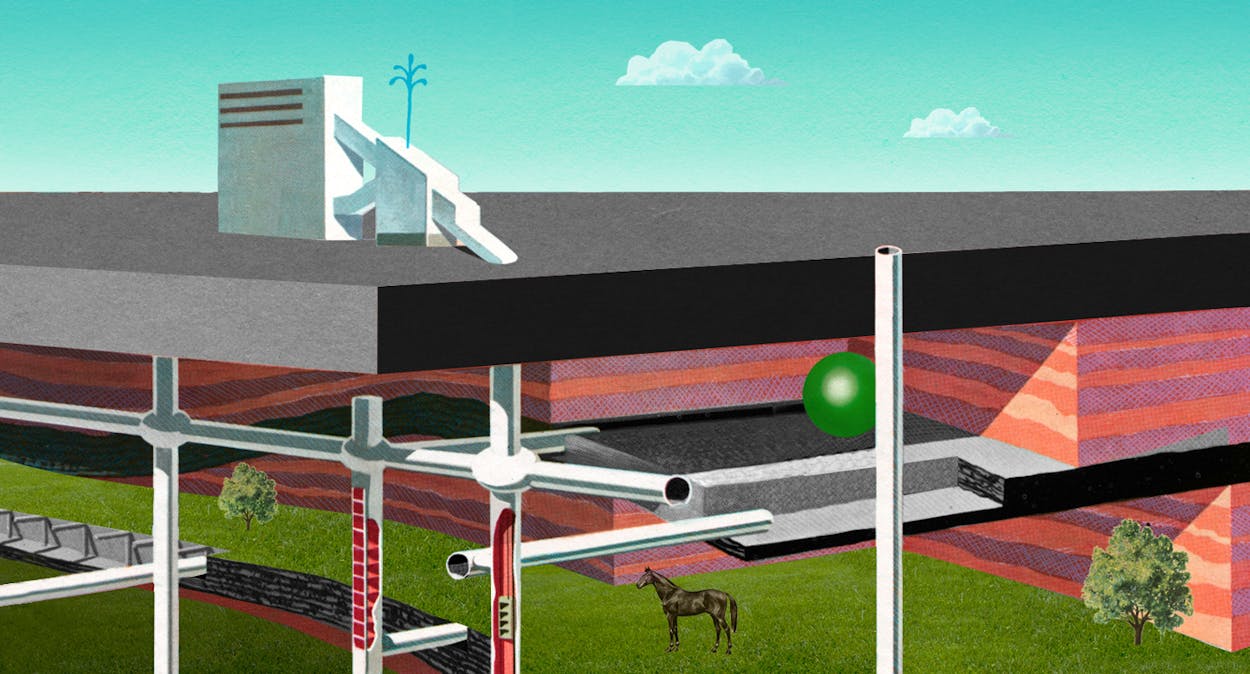

The answer to that question was a surprising one: the fountain marked the future entrance of a high-end, doomsday-resistant community that a group of investors from McKinney hoped to build for $330 million. Their plans, as residents would finally learn from a TV news report in early November, were to transform a seven-hundred-acre piece of land into a sustainable, off-the-grid community known as Trident Lakes, with 532 earth-sheltered condos set around three white-sand lagoons. Soon a flurry of headlines followed, from the Associated Press (“Texas investors build bunker homes for doomsday scenario”), Forbes (“Inside Trident Lakes, a Luxury Doomsday Escape That Comes With Nuclear War Protection and DNA Vault”), The Atlantic (“A resort for the apocalypse”) and even a half-page spread in the Wall Street Journal’s Mansion Section (“Luxury for the Apocalypse.”)

Building a fallout shelter to weather the worst is hardly a new idea, of course. Back in August 1955, Fannin County’s most famous son, Speaker of the House Sam Rayburn, helped Senate majority leader Lyndon B. Johnson pick the location for the congressional doomsday bunker, settling on the Greenbrier, in West Virginia. (Rayburn’s two-story clapboard home happens to sit some six miles down the road from the Trident Lakes site.) And at the height of the Cold War, John F. Kennedy famously advocated that every American “prepare for all eventualities.” But in our particularly anxious present, a section of America has experienced a return to this mind-set—there is terrorism to fear, or nuclear war, or a devastating pandemic, or an electromagnetic pulse—and with it, there’s been a rise of projects catering specifically to the one percent.

Take, for instance, Rising S Bunkers, in Murchison, which offers a line of custom, reinforced-steel bunkers that can be buried in your backyard, starting at $39,500 for a basic “mini-bunker” and ranging up to the $8,350,000 Aristocrat, which boasts a gun range, a pool, and a greenhouse. According to general manager Gary Lynch, the sales of the company’s luxury bunkers have jumped 700 percent in the past year. (When I visited, Lynch let me walk through a partially completed 1,200-square-foot bunker bound for Saudi Arabia. The door to the sleeping quarters was disguised as a built-in bookshelf.) In Kansas, there’s the $20 million Survival Condo project, built into an abandoned Atlas missile silo. (The twelve condos in the first silo were priced at between $1.5 and $3 million and have completely sold out. Construction in a second silo is planned.) And in Germany, there’s Vivos Europa One, a 227,904-square-foot Cold War munitions storage facility that is being repurposed to house up to five hundred people on an invitation-only basis.

But none have been done on the scale (or at the projected price) of the Trident Lakes project, which will include an eighteen-hole golf course, a 100,000-square-foot equestrian center, polo fields, gun ranges, tennis courts, and a community center connected to the bunkers via an underground network of tunnels. There will also be helipads, and, if the adjoining land can be purchased, a runway long enough to accommodate private jets. If the market for this kind of real estate product is niche, it is, by all accounts, growing. “The idea that everything would collapse at once is a classic black swan event, but clearly there are people thinking along those lines,” Greg Hallman, a senior lecturer at the University of Texas at Austin’s McCombs School of Business, told me. (Hallman specializes in real-estate finance.) It is also a way to buy land cheaply and then sell it at city prices, he said. “It’s certainly a way to profit from people’s fear.”

All that stands for now is the fountain, but in late February, I decided I should see the Trident Lakes site for myself. I emailed the project’s spokesman, Richie Whitt, a longtime fixture of the sportswriting scene in Dallas and Fort Worth, and he agreed to meet me by the front gate for a tour. After I hopped into his small SUV, he pointed out where a statue of Poseidon will be perched atop the gate. We crossed a set of railroad tracks, and as the land turned into rolling hills dotted with pecan trees, Whitt showed me where the bunker condos will be built. Bulldozers and other earthmovers were already flattening out the orange and brown dirt. “This isn’t an antiquated Cold War steel box ten feet underground. I’m not sure that we cater to the guy who has his money in the mattress and all his food in cans in the barn,” said Whitt when we made it to his office, in a limestone house near the center of the property. “This is going to be one of the nicest private country clubs in Texas, if not the U.S. Our grand vision is to provide our customers with a luxurious, safe place.”

The idea for Trident Lakes developed, Whitt explained, over the course of various cocktail parties in Dallas, where a group of people discovered their mutual alarm over terrorism and police shootings and decided to prepare for “a very murky future.” When I asked what prospective customers say they’re concerned about, Whitt told me, “We’ve been surprised by the almost equal distribution of people who say, ‘I’m scared of Trump because he’s going to take us to war’ and then those who say, ‘I’m scared of the Trump opposition that’s trying to overthrow the government.’ And, for all of them, that fear manifests itself in, ‘Okay, what do I do about it?’ We’re finding out that there’s no shortage of things to be scared about.”

Interest in the development has been high. So far, Trident Lakes has more than one thousand people on its waiting list, and around four hundred of those have responded to a five-page questionnaire asking about their education level, religion, marital status, yearly income, net worth, and career. One question was “How would you characterize your temperament in times of extreme adversity?” with the choice of answers being calm, frenetic, passive, aggressive, intellectual, or physical. According to Whitt, a full 71 percent of respondents have said they are attracted to Trident Lakes primarily because of its security.

Later that afternoon, at a deli in Mc-Kinney, Trident Lakes’ CEO, Jim O’Connor, shared more details between spoonfuls of tomato soup. He spoke excitedly about the sustainable systems they hope to install, including solar and natural-gas power options, a closed wastewater treatment plant, and even a Swedish water-recirculation system and Italian artificial skylights. He and his team are refining plans for a 2,890-square-foot version of a condo, as well as a 4,000-square-foot one, he said. Their market analysis revealed that similar properties sell between $270 and $330 per square foot, but they wanted to set the price for the first twelve condos in an online auction this summer, after receiving wastewater permits and hammering out a homeowners’ association agreement with their attorneys. Upon winning an auction, O’Connor said, a prospective homeowner would sign a binding letter of intent and put down one percent of the purchase price. If interest is great, they could possibly auction off all the condo units. “It’s basically raw land still, so if we can build the whole project in one phase, and build all the infrastructure at the same time, we’ll be more efficient and more profitable,” he told me.

I left the interview convinced of O’Connor’s passion. But something about his manner also left me unsettled. My mind kept circling back to the fountain, which seemed a very Potemkin flourish at the outset of a construction project. It was also the kind of strange, loud signpost that, in the event the world did end, would actually lead the people with pitchforks right to its doorstep. Wanting to learn more, I decided to look into things further.

The first mention of Trident Lakes I could find anywhere came in a press release from last September announcing a fundraiser that John Eckerd, identified as the company’s chairman, planned to hold at his home for Generation Rescue, actress Jenny McCarthy’s autism foundation. (That McCarthy is a highly controversial figure for promoting the view that vaccines may cause autism does not seem to trouble anyone involved, as the development’s equestrian complex will be named Generation Rescue Equestrian Center at Trident Lakes.) The occasion, held on October 1 and called A Night of Hope, was attended by several Real Housewives of Dallas and New Jersey, and other B- and C-list celebrities. Eckerd, who is bald, wore a silky purple shirt with the top button unbuttoned. His wife opted for a long black gown.

As I did more reading about Eckerd, I learned that the 53-year-old, who was born in Los Angeles and raised outside Pittsburgh, has a long and colorful entrepreneurial history—the kind of risk-taking career that seems to have brought him at least as many losses as wins. In the nineties and early aughts, he produced instructional sports videos, including a well-received one featuring Mia Hamm. (Another, “Dallas Cowboys Cheerleaders Country Western Workout,” was a flop.) He then turned his efforts to less wholesome pursuits, including Racetrack Girls Go Nutz, a racy video series modeled on Girls Gone Wild and filmed at NASCAR races. (“You will blow a gasket when you see all the uncensored girls that our camera crews caught on tape. From Dallas to Daytona Beach, Atlanta to Talladega, you get a front row seat to all the hot action,” read the website.)

Over the years, he’d attracted a fair share of media attention. Though a 2002 profile of Eckerd in the Wall Street Journal had described him as “in the midst of his big leap,” in November 2007, the Dallas Morning News devoted more than six thousand words to Eckerd after NASCAR sued him and his company Consolidated Sports Media Group for trademark infringement. In fact, in the past twenty years, he has been the defendant in at least nineteen legal proceedings in five states. More recently, Eckerd owned two companies, Armor Horse Manufacturing and Vault Motor Co., that built up-armored limousines, some featuring mood lighting and retractable stripper poles. But both ventures are now defunct, and a federal court issued a $359,598 default judgment against Armor Horse and its manager in 2013 for breach of contract.

Trident Lakes chief executive O’Connor, I learned, had been the CEO of Vault Motor Co. Curious about this history—and the involvement of a businessman with such a mixed track record in a high-stakes venture like Trident Lakes—I reached out to him and Whitt again to ask about Eckerd’s role. They responded quickly, explaining that, while Eckerd had indeed been chairman of Trident Lakes in early 2016, he had stepped down in July of that year due, in part, to health concerns. His role as chairman, they said, had primarily been to facilitate the land acquisition deal for the project; now his relationship to Trident Lakes was merely as an adviser.

Eckerd declined my request for an interview, but he did, in an email, point me to his website, which documents his “provocative path” as an entrepreneur and promotes his forthcoming autobiography, Blood, Sweat & Cheers. “Stay in business 35 years and you’re bound to find yourself on one end or other of litigation,” he explains on one page of the website. The exact nature and outcome of this litigation is not addressed. “There have been hits. Misses. Bigger misses. Lawsuits. Bankruptcy. Allegations. Scandals. Ups. Downs. Flirtations with rock bottom. 30,000-foot highs in private jets.” In his email to me, he confirmed his role in “defining the real-estate transaction strategy” for Trident Lakes, but declined to “rehash very old news” about his business record. He felt my focus on his past was misguided. “Trident Lakes is a disruptive project that is utilizing some amazing technologies and has some very high-profile people on board,” he wrote. “From what I hear, some of the announcements yet to come are the real story.”

What will that real story be? Perhaps it depends on your vantage point—whether you believe that the end of the world is near, whether you have the money to bet on your future comfort, whether you’re a chairman or CEO with a penchant for risk and spinning dreams, or whether you’re like me, a skeptical journalist. When I sent O’Connor, Whitt, and Eckerd some follow-up queries about the source of funding for Trident Lakes, Eckerd emailed back to say that Trident Lakes had, in its early development, been “self-funded by board members” but would soon be announcing “a deal to begin the process of identifying capital partners for the fulfillment of the project.” Whitt confirmed this, saying that a press release regarding the project’s financing was imminent. (That press release, received just as this story went to the printer, announced that Boston-based financial services firm Detwiler Fenton had been retained to help raise some $200 million in capital.) Eckerd had offered “introductions to institutional financiers,” per his original correspondence, and O’Connor had spoken of “prominent” board members during our initial meeting. But who these board members were, or how many of them were involved in Trident Lakes, was not information I could glean.

I pondered this for a long time. Was Trident Lakes indeed a visionary project? Or a dubious one? Was I to hope, for the sake of those whose fears it relieves, for its success as the ultimate gamble? Or was the financial risk so great as to make it the ultimate fool’s errand? The answer, again, depends on your perspective.

- More About:

- Style & Design

- Architecture