From 1993 to 2003, more than three hundred young women were brutally murdered in Ciudad Juárez, across the Rio Grande from El Paso. Some were killed by husbands and boyfriends, but many died at the hands of unknown killers. In many cases, they disappeared from the streets in broad daylight, and their bodies later turned up in the desert. In November 2001, a group of eight women’s bodies were found. It seemed as if some kind of ritualized, serial killing was going on.

Cecilia Ballí jumped at the chance to report the story for Texas Monthly. She had grown up in Brownsville and traveled back and forth across the border her whole life. “I was a little naive about it,” she told me. “I thought, ‘I can do this.’ ”

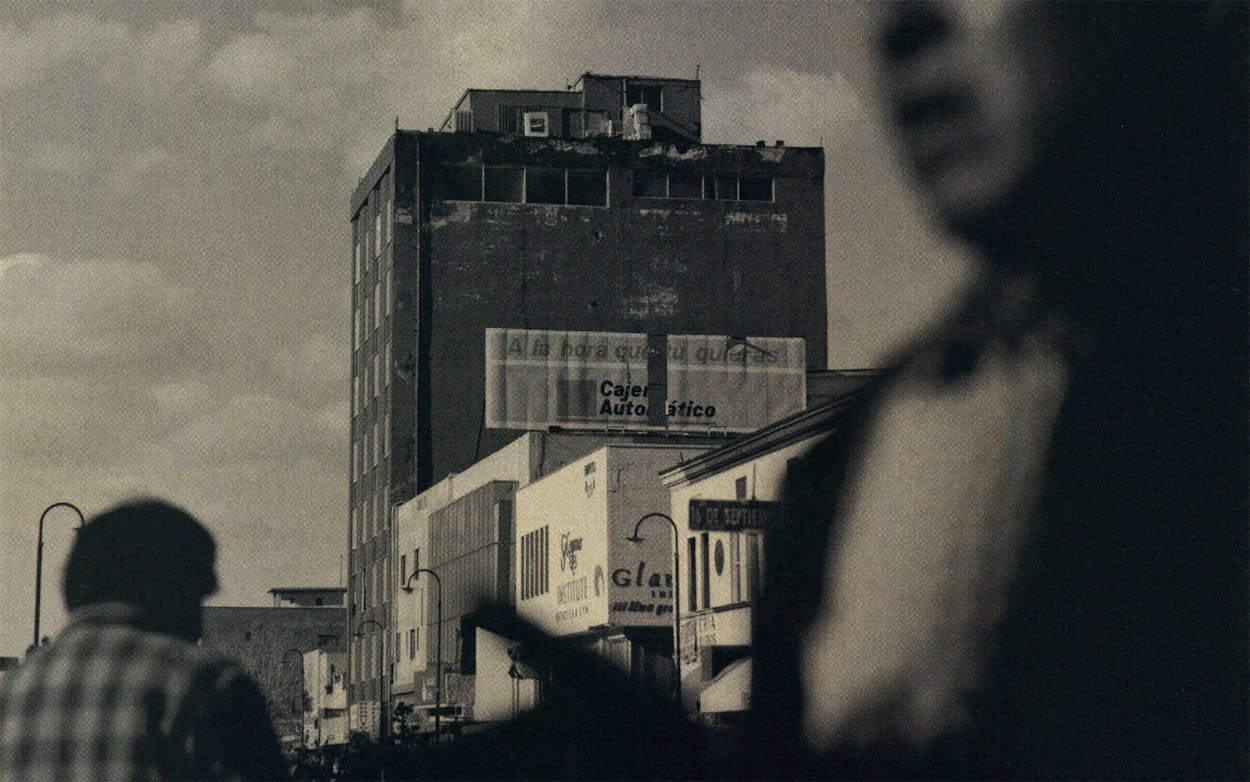

The result was a heartbreaking story, some of it told from the point of view of a teenage victim’s mother, some of it told from Ballí’s own experience, as the young reporter, who was 26 at the time, walked the streets of Juárez. At one point, a man approached her outside of a restaurant where she had been eating lunch. There was no one else around. “Are you looking for work?” he asked her. Simple entreaties like this had led to the abductions of many victims. Ballí—suddenly aware of her precarious situation—felt terrified. She stuttered, “No.” She finally said that she was an American, and the man turned to walk away. When her instincts kicked in and she asked about the job, he turned and said, “I hire girls to work at a grocery store.” When Ballí went into the restaurant, the man followed her and stood in the door. “Come on, let’s sit down,” he told her. “Let me buy you a drink. En confianza.” You can trust me. Ballí walked away.

The incident left her feeling like she had been one of the lucky ones. When she told her editor, the late Paul Burka, about the encounter, he insisted she use the experience to make the story resonate with readers. “You have to write this story from personal experience,” he said. Although she didn’t want to be the focus of the story, she did include a chilling description of her brush with the self-identified job recruiter near the end of the article. Now, almost twenty years after “Ciudad de la Muerte” was published in 2003, that anecdote remains powerful because she connected her life with those of the women of Juárez. “I had felt my heart beat,” she wrote, “the way they must have felt it beat too.”

And it made her realize that these women weren’t naive, stupid, or irresponsible, as many in law enforcement and media had portrayed them. “When I experienced that encounter in broad daylight,” Ballí said recently, “the way he put it to me—‘I hire girls to work at a grocery store’—I realized if I’d been sixteen and lived in Juárez, how easily it could happen. That’s when it hit me: these poor girls, they could just be walking around, doing their thing, then this could happen.”