Of all of Houston’s notable museums and art spaces, the Menil Collection perhaps had the most curious start. Established as the public home for John and Dominique de Menil’s private art collection, which was gathered over four decades, “the Menil Collection is spectacular in scope if rarely transcendent in quality,” according to longtime Texas Monthly contributor and award-winning novelist and journalist Michael Ennis, in “New Kid on the Block,” his 1987 profile of the new museum and its founding director, Walter Hopps.

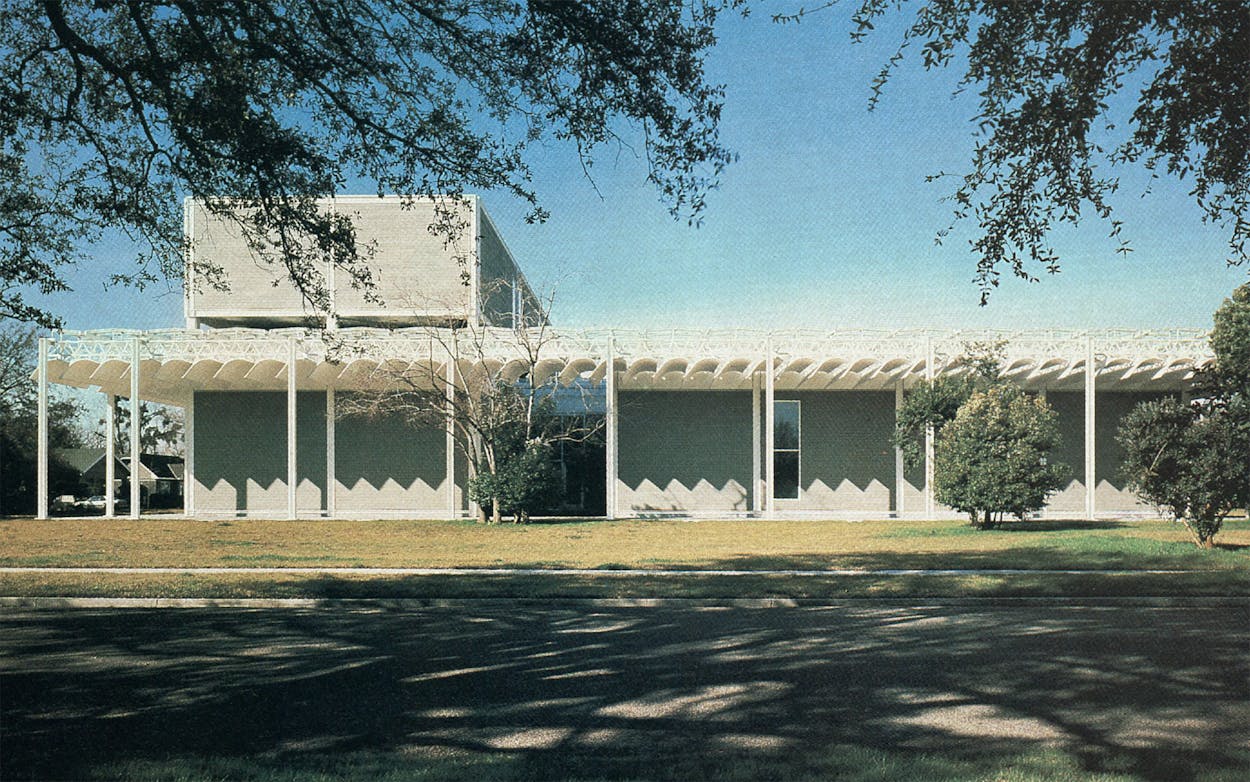

While much had been written on the de Menils and their acquisitions, Ennis shone a new light, deftly exploring the museum structure and its architect, Renzo Piano, as he homed in on the controversial director, Hopps. Ennis’s descriptions of the building’s design and the museum director were as kinetic as the art collection itself. Ennis’s profile focused on the eclectic drivers of the museum, giving readers a clear picture of what to expect when the it opened 35 years ago. The Menil astounds me to this day, and we have Hopps to thank for much of it.

Hired in 1979—eight years before the building was finished—and named director the next year, Hopps had a reputation for being part of an itinerant culturati. He was as comfortable in smoke-filled coffeehouses populated with finger-snapping beat poets as he was at exhibition premieres hosted by high-society collectors. Hopps’s taste in art was just as diverse, giving him the skills to guide and present an assemblage as vast as the Menil Collection. Ennis put it another way: “the opening of the Menil Collection will provide a more accessible focus for Hopps’s wide-ranging—some would say rampaging—intellect.” When Hopps came to work for Dominique de Menil, his résumé was already impressive. He had established several galleries in Los Angeles and had worked as director or curator for the Pasadena Art Museum in California, the Corcoran Gallery of Art, and the Smithsonian’s American art museum, as well as serving as the U.S. commissioner for international biennial art exhibitions.

Hopps wasn’t a native Texan, but his brashness fit right in. He told Ennis, “Each year I hope we have less attendance because the quality of the experience will be greater for those who do come.” This dynamism was ideal for the striking manifestation of the Menil Collection. Still, there were doubts, Ennis explains. Would the public embrace the building, the director, and the extensive collection of 10,000 items? Even in a city renowned for its museums and cultural centers, Ennis thought yes. He was right. The Menil Collection has expanded into a campus that includes the Cy Twombly Gallery, Richmond Hall, the Menil Drawing Institute, the Byzantine Fresco Chapel, and a separate bistro. Houston’s art and culture scene was better for it. Ennis wrote as much in a 2002 Texas Monthly article, mentioning “the whole extraordinary Menil legacy, from the Rothko Chapel to an entire building devoted to Cy Twombly, an artist whose work is so reconditely hip that 60 Minutes once trashed it for being so reconditely hip.”

The success isn’t surprising. Though Ennis is a novelist and a journalist who has written as adeptly about politics and as he has the outdoors, his Texas Monthly arts and design coverage, published from the late 1970s through the 2010s, stands out. Like Hopps, Ennis challenged the state’s mainstream art views. Instead of gallery placement and the lighting of a space to feature cutting-edge art, Ennis’s craft is the written word.